Dimebag Darrell – the Far Beyond Driven interview: “I knew it was going to be one bad motherf**ker – refreshing, new, and that’s what it was”

In this 1994 GW interview, Pantera’s larger-than-life guitarist opens up about his musical upbringing, the parallels with the Van Halen brothers, Randy Rhoads’ influence, and the noises and tones behind the band’s uncompromising new sound

This archive feature was originally published in the April 1994 issue of Guitar World, which hit newsstands just before the release of Pantera's Far Beyond Driven.

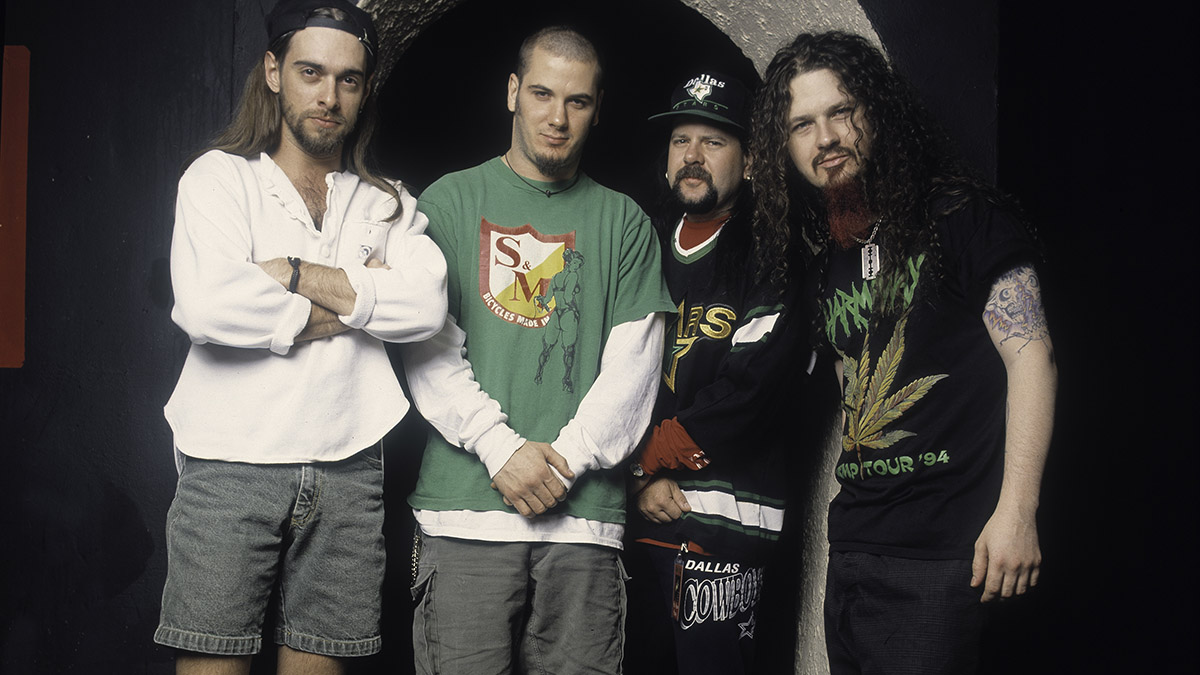

Dimebag Darrell Abbott, Pantera’s high priest of six-string destruction, is feeling ornery. His eyes narrow as he slowly picks up his metallic blue Dean electric guitar. Cradling it like a sawed-off shotgun, the self-proclaimed “cowboy from hell” begins to frown. It’s obvious that he has something urgent on his mind.

“I grew up a heavy metal kid and we are a heavy metal band,” he growls in a rapid-fire Texas twang. “I know it’s not fashionable, but I’m proud to say that’s what we are and that’s what we do. It kills me when I see some metal band trying to pass themselves off as an ‘alternative band.’ Well, dude, they can join the pack, but we’ll remain true to our roots while shit keeps twisting around us.”

And twist it does. While the rest of the rock world continues to be preoccupied with the next big Lollapaloser, Pantera has been steadily reinventing and reinvigorating metal for the Nineties. By combing the rawest elements of thrash, Texas blues and hardcore, the band has created a new form of metal – one that is rhythmically aggressive, sophisticated in construction, and, yes, even hip.

At the epicenter of Pantera’s musical mosh pit is the band’s larger-than-life guitarist, Dimebag Darrell. His trademark crimson goatee, custom guitar and colorful command of good ol’ boy slang has made him a hero among hard rock fans.

But his bone-rattling rhythm work, inventive soloing and distinctive razor-sharp “Darrell tone” is what has made him a legend among a whole generation of guitarists searching for a new Edward Van Halen. And like Van Halen, the key to the Texan’s large talent is his healthy disregard for rules and regulations.

“The worst advice I ever received from my dad was to play by the book,” explains Darrell. “My old man used to flip out whenever I would try to branch out and do something different. Although he didn’t do it on purpose, he really held me back in the beginning.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He owned a recording studio in our hometown of Pantego, and if something was a little too hot on tape or was distorted, he’d say, ‘Don’t do that Darrell – do it by the book.’ My sound didn't develop until I started ignoring the recording manual.

“It’s funny, because he still doesn’t really understand what we do. When he heard Fucking Hostile on Vulgar Display Of Power, he absolutely freaked! He told me, ‘Son, people are going to think somethin’ is wrong with the record and take it back.’”

On Pantera's latest release, Far Beyond Driven, Darrell continues to ignore his bookish dad’s advice. In addition to his usual wicked rhythm and lead work, the guitarist has introduced a noisy, new industrial slant into his playing.

By cleverly manipulating bursts of dissonant white-hot feedback on several tracks, he has added yet another startlingly abrasive dimension to his already distinctive approach. More surprising still is Darrell and his band’s sensitive acoustic reading of Black Sabbath’s psychedelic chestnut, Planet Caravan.

When my dad heard F**king Hostile on Vulgar Display of Power, he absolutely freaked! He told me, Son, people are going to think somethin' is wrong with the record and take it back

Before our interview begins, he hyperactively bounces over to a battered guitar case that is held shut by three strips of heavy-duty duct tape. (“All the latches are rusted or broken from touring,” he explains.) After rifling through its contents, he produces a pick that appears to have been hacked with a rusty pocket knife.

“Check the grooves,” Darrell says, shoving the scarred plectrum in my direction. “I’ve also had my volume knob sliced up.”

When asked why, he answers with a demented grin, “They're sweat-proof!”And, like their owner, a little rough around the edges.

I understand that when you were a kid, your father was a musician, and that he owned a recording studio, in Pantego, Texas, where you grew up. Did he have any impact on your decision to pick up the guitar?

“Absolutely. My old man was a musician -- that's what he did for a living. And like most fathers , occasionally he’d let me visit where he worked. So I started going to his recording studio and I really dug it.”

Do you have any memories of those early visits?

“Sure. A Pantego radio station used to sponsor local talent, and the bands would cut tracks in my dad's studio. I’d always squeeze in there and try to check their shit out. When you’re a little kid, you have nerve. I'd walk right up to whoever was recording and say, ‘Hey, dude, what's the lick of the week?’ I’d be strappin’ them dudes up, and getting them to show me their shit.”

Did your dad encourage you to play guitar?

“Encourage me? No, I wouldn’t say that. But the opportunity to become a musician was always there. For example, I can remember one birthday of mine where he said, ‘Son, you can either have a BMX bike or you can have this,’ and he pointed to a guitar. I ended up taking the bike, but he did plant a seed in my mind.

“I think he might have been a little reluctant to push me into music because he had seen enough of the rock-and-roll lifestyle to know that it’s probably not the best thing to pursue. It would be the same as saying, ‘Here, go sell your soul to the devil.’ It’s not something you want for your son. You know that phrase, ‘Sold your soul to rock and roll’? It ain't full of shit, man! [laughs]”

So when did you decide to sell your soul?

“When I discovered Ace Frehley and Black Sabbath, dude. I went back to my old man and asked if I could trade my bike back for the guitar. [laughs] Actually, I didn't ask him that, but if I was slick, that's what I would’ve done! I didn’t get my first guitar until my next birthday. I was about 11, and he gave me a Les Paul copy and a Pignose amp.

“Initially, I just used the guitar as a prop. I’d pose with it in front of a mirror in my Kiss makeup when I was skipping school. Then I figured out how to play the main riff to Deep Purple’s Smoke on the Water on just the E string.

“Next, my old man showed me how to play barre chords, and that's when things started getting really heavy. But I think the turning point came when I discovered an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Fuzz. Feedback! Distortion! Dude, that was all she wrote.”

Did you ever get to work in your father’s studio?

“Yeah, he’d pay me 20 bucks here and there to do piano overdubs or punch-ins while he was trying to do his vocals. So I learned quite a bit at an early age about how a studio works. However, my brother Vinnie [Paul, Pantera drummer] is really the guy that followed in my old man’s footsteps.

“He’s a complete gadget hound and really knows his way around a studio. Vinnie, in fact, is partly responsible for my sound.On our early demos, I was really frustrated with my recorded sound. I'd tell my dad, ‘Dude, I want more cut on my guitar – I want more treble.’

“And he’d say, ‘Now, son, you don’t want that. It’ll hurt your ears.’ But my dad just didn’t understand. Then Vinnie started getting behind the boards. That's when things started to sound the way I wanted them to sound.”

Could you use the studio any time you wanted to?

“Nope! No fuckin’ way. And we never abused the privilege. The local motherfuckers who knew that my dad owned a studio would say, ‘Ahh, dude is spoiled,’ and this and that. But we didn’t abuse it at all. I’d always ask if we could use the studio first, and if our dad didn't want us there he would tell us, and that was that. But I definitely tried to get down there as often as I could. [laughs]”

Did your dad have any good advice regarding the music business?

“Yeah: ‘Write your own music.’”

What’s the worst advice he gave you?

“To play by the rules. To tum down the treble knob because it will hurt someone’s ears. My old man used to flip out whenever I would try to branch out and do something different. Although he didn't do it on purpose, he really held me back in the beginning. If something was a little too hot on tape or was distorted, he’d say, ‘Don't do that, Darrell – do it by the book.’”

You mentioned that your father taught you your first barre chords. Did he show you anything else?

“I would go over to his house on weekends, bring a record of a tune that I wanted to learn, and he would show me how to play it. I think I took Cocaine over there the first time; not the drug, of course – the Eric Clapton tune. First he showed me a basic barre chord version, then he showed me other ways to approach it with different chord inversions. So I would get little bits of information from him like that.

“I also learned how to pick things off of records from him. That was back when people still listened to records. [laughs] I’d watch how he tuned to records, and he’d say something like, ‘Son, these guys tune way down.’ And I’d ask him, ‘You mean there’s a standard tuning?’ I was completely clueless. He’d just help me put together the pieces. I watched how he did it and started doing it on my own at home.

I respect people that can read tablature and all that shit, but I just don't even have the patience to read the newspaper

So you never had any formal lessons?

“Naw. I tried one time. I was in a rut and I wasn't getting anywhere, so I thought I’d just go up the street and get a guitar lesson off this cat. He wrote down some weird scale and tried to explain how it worked. After we finished he said, ‘Now go on home, practice that scale, and show me how well you can play it next week.’

“So I took it home, played around with it for a few minutes and said, ‘Fuck this, I just want to jam.’ I respect people that can read tablature and all that shit, but I just don't even have the patience to read the newspaper. I’ll read three or four lines and that’s it.”

When did your brother Vinnie start playing drums?

“That’s a good story. One day Vinnie came home from school with a fuckin’ tuba. My old man said, ‘Son, you won't be able to make a penny playing that thing. Take it back right now and tell them that you’re going to play drums!’ A year later, I tried to hop on Vinnie's kit and hang with him, but Vinnie just blew me away.

“Our story is almost identical to the Van Halen story. Both Eddie and Alex played drums, but Alex killed, so Eddie decided to pick up the guitar. It was the same in our case. Rigs [Vinnie's nickname] definitely dominated me on the kit so I started playing guitar.”

Our story is almost identical to the Van Halen story. Both Eddie and Alex played drums, but Alex killed, so Eddie decided to pick up the guitar. It was the same in our case

How did Vinnie influence you?

“Vinnie taught me a lot about timing. For example, I can remember one day we decided that we were going to try to learn More Than a Feeling, by Boston. We started jamming on it right before we had to leave for school. We were already late when Vinnie pointed out that I had left out one chord – that I was coming out of one section before the beat had a chance to turn around.

“I’m like, ‘What are you talking about?’ So he counted everything out for me and showed me where I was missing a chord. We went back and listened to the record and, sure enough, he was right. It's always been like that. Vinnie is very knowledgeable. He was the one that paid attention in school! He learned all his drum rudiments.”

What’s it like playing in a band with your brother?

“Great. We’re more like best friends. I think we have a better relationship than most brothers because we're working for the same goal. In most families, one brother will be a doctor and the other will be a lawyer, or a street bum – however it works out. I don’t even know how to put this without sounding wacky, but we don’t have a ‘push/pull’ relationship at all. It’s just very natural; we don’t fight and shit.”

Was there ever any rivalry between you?

“A little bit, but not much. He always had the business sense and I had the street-level sense. We both respect our differences and, luckily, we’re able to just kind of put the two together. But now that I think about it, he did kick my ass a few times when we were growing up. [laughs] All I can say is that I'm fortunate to have a brother that can rip on the drums like Vinnie Paul. I mean, it’s hard enough to find someone that can just beat on the skins.

What do you contribute to Pantera’s songwriting process?

“Every song is different. There are no plans, no formulas . We know it’s got to jam, and that’s about it. When we started this album, I didn't have as many riffs written as I've had in the past, but I had a vision of what I wanted. I knew it was going to be one bad motherfucker – refreshing, new, and that’s what it was.”

How do you write your riffs?

“A couple of songs were actually written in concert. If you improvise a riff and the crowd immediately reacts to it, you know you're on to something.You rarely hear of a band that will take a chance on improvising new riffs on stage these days. Everyone seems so well-rehearsed and conservative. Ah shit, you know us – the most dangerous band in heavy metal!

We wrote practically all of 25 Years, off the new album, in concert. One night, in front of a packed house, we just started jamming and came up with the main riff

“Let me tell you a story. We wrote practically all of 25 Years, off the new album, in concert. One night, in front of a packed house, we just started jamming and came up with the main riff in the song. Phil was really getting into it and he started making suggestions while we were playing. At one point he told us to stop. So we stopped. And he said, ‘Dudes, go into a straight chug right there.’

“This is in front of hundreds of people! We just put the crowd on hold for a few minutes while we put the song together. I don’t think anybody minded, they just sat there and checked us out while we worked things through.”

How is this album different for you?

“We’ve been getting into the band thing. I've been trying to look more at the big picture – trying to figure out what's appropriate for the tune. For example, we were working on this very aggressive song called Slaughtered, and at first we decided that we were going to insert a slow, melodic lead guitar part into the middle of the tune.

“But while we were working on the slow section, everyone was just sipping on their beers and staying kind of quiet. Then I realized that the tune had lost its momentum and its power, so I said, ‘Fuck the lead.’ The big picture, man, that’s where it’s at.

Five Minutes Alone is another of the album’s songs that features a pretty minimalist lead.

“In my Guitar World column [Riffer Madness], I’m always talking about getting on one note and holding it, feeling it. So one day I was out in my garage, just dicking around on my eight-track, trying to figure out what Five Minutes Alone needed.

“Since I was only going to take a short solo, I started asking myself, ‘Do I need to burn something real quick for the sake of burning?’ ‘Never,’ was the answer. Then I thought, ‘Why don’t you take your own advice?’ So I hit that one note and it really felt good.

“At first I was going to hop off of it, but then I thought, ‘No, the one note, dude.’ And I hung, and hung, and hung. Then I started bending the string up and down until it sounded like a siren, and that is all that song needed.

I noticed an experimental edge on the new album: Good Friends and a Bottle of Pills has an almost industrial feel. Hard Lines, Sunken Cheeks is epic in length and mood. And your cover of Black Sabbath’s Planet Caravan even features bongos and acoustic guitars. Did you intentionally set out to broaden the band's vision?

“We never plan anything; we just let nature take its course. But if you ask me, we did broaden our vision on this album. Actually, when I presented a demo of Hard Lines, Sunken Cheeks to the band, I thought I’d get mixed reactions, at best. But everybody dug it, and Phil saw the possibilities right away.

Musicians tend to get bored playing the same thing over and over, so I think it’s natural to experiment. On Good Friends, for example, instead of playing a traditional solo, I just opened my guitar up all the way and let it feed back for effect.

That’s a cool section, but it sounds like the feedback is being effected somehow.

“Good ears, dude. I discovered the pure feedback wasn’t quite enough, so I added a DigiTech Whammy Pedal to the equation, which helped produce a sound that was completely fucked up!”

I hear the Digitech Whammy Pedal on several other tracks. You used the pedal’s harmonizer feature on the solo for Strength Beyond Strength. How did you have it set?

“I don’t really know! Like I said before, I don't really have any training in theory, so I just kept turning knobs until I found the most wicked sound. Actually, there are two guitars playing that lead.

“One is playing the lead without effects, another guitar is doubling it with the Whammy Pedal, and both are going through one of those little 10-watt Marshall heads to produce what I call my ‘fry sound.’ It’s the sound that I get on my eight-track demos.”

Is that the Whammy again on Becoming?

“Yes, sir. I’m using it on the rhythm part. I depress it on the third beat of every other measure to produce what Phil calls the ‘step on the cat’ effect. It’s too bad that you noticed it was a Whammy Pedal, because we were going to tell people that we were abusing an animal to produce that sound – you know, ‘We were jumping on a cat, then we simply plugged a cord up its ass and threw a little EQ on it.’

The only thing I had between my guitar and my amp was my Dunlop wah and the Whammy, so like an idiot I decided to try and play my solo using both effects simultaneously

“That was one of the songs that started with Vinnie’s incredible drum groove. Because I used the Whammy Pedal on the rhythm part, I decided to use it on the lead as well. The only thing I had between my guitar and my amp was my Dunlop wah and the Whammy, so like an idiot I decided to try and play my solo using both effects simultaneously.

“I figured it was going to sound horrible, but everyone started saying, ‘That’s cool, dude, that’s cool.’ So I kept it, and then I doubled it and it was done! I know some of your readers are going to rag at me and say, ‘Aw, dude, anybody could’ve done that.’ But let me tell you, I’m the kind of dude that would do that. And on the record, not at ‘show and tell.’

When I first heard Becoming, I thought, ‘Someone is actually corning up with some new sounds.’

“Noises, dude! Tones and noises!”

While we’re on the subject of rude noises, what’s going on at the beginning of Good Friends and a Bottle of Pills?

“I was standing next to Vinnie, who plays drums really hard, and I was slowly moving my volume knob to see how far I could go before the guitar started feeding back. I had my guitar running through an old MXR flanger, and my intention was to just make a little bit of racket in the beginning of the song.

“Just by chance, the pickup started picking up Vinnie’s snare drum and it popped the gate open. So the drum is actually triggering the guitar, and that’s what you hear.”

Are you playing any chords?

“Naw, I’m just standing there drunk, fucking around with my volume knob. [laughs]”

Since we're interested in details, what were you drinking?

“Coors Light, dude.”

Let’s talk about a solo where you do let your fingers fly. The double-tracked lead on I'm Broken sounds like an homage to Randy Rhoads.

“All right! You heard that? That's right on the money. People always ask me about my influences. I learned about double-tracking leads from Randy – especially the way he played them. He played them tight but loose, so they would flange just a little, and that's what I tried to do on I’m Broken.”

Was Randy important to you?

“Fuck, yes. If he was still around, there’d be no telling what that cat would be bustin’ off. To me, Eddie Van Halen was heavy rock and roll, but Randy was heavy metal.”

I wish sometimes I could just do an Edward Van Halen – a rhythm track on one side, reverb on the other, and leave it alone. But that's not my style

Do you fuss much over your parts?

“I try to do things in one take, but doubling rhythm parts is always difficult, especially if you want things to cut the way I want them to cut. Each track has to be precise, and that is a problem on a rhythmically complex track like Slaughtered.

“The first run through is always cool, but the second is always a bitch. In fact, I think Slaughtered was the most difficult track on the album. It was a nightmare to double. It’s the shit once you're done with it, but getting there is hell.

“We actually went with more loose doubles than on our previous records, but sometimes it has to be right on the money and that’s where the fussing comes in. I mean, goddamn, I wish sometimes I could just do an Edward Van Halen – a rhythm track on one side, reverb on the other, and leave it alone. But that's not my style.”

What was your workhorse amp and guitar?

“I stuck to what I've always used – Randall amps, and my main guitar is still my blue ’81 Dean with the Kiss stickers. That guitar just can’t be topped. I use that on all the songs that are in standard tuning. When we tune down to D, I use my brown tobacco-burst Dean.

“The only thing that was really different on this album is that the signal from my guitar was routed through three Randall amps which were recorded simultaneously on each track – three amps mixed down to one track.

“One stack was effected with my MXR flanger, for a kind of hollow sound; another stack was just straight up and dry, and the third was set similar to the dry stack except that it had a little more gain. Separately, one sounded horrible, one sounded great and the other sounded bassy; but together they sounded incredible.”

I know you’re a fan of vintage effects pedals, like the MXR flanger. Where do you get them?

“Pawn shops, man.”

Where are the best pawn shops?

“The best ones are anywhere where the owner doesn’t know the value of his merchandise. [laughs] Part of the fun is just talking trash with the dudes that run the shops. It’s like, ‘Dude, what's up with this fuckin’ thing?’ One time I was checking out some guitars, amps and effects at a pawn shop and the store owner unintentionally gave me a defective cord. So I plugged it into an effect that I wanted and started kicking the box around so the cord would crackle.

“As soon as I got the store owner's attention, I started pretending it was the effects box that was broken. I started cursing and calling the effect a ‘no good piece of shit.’ He said, ‘It was working fine three weeks ago. We gave up 30 bucks for that thing.’ So I said, ‘Well, it can sit here and rot then. Nobody’s gonna pay for this thing.’ In the end, the dude sold it to me for five bucks!

Since this interview will appear in our special Survival Guide issue, I wanted to ask you a few questions about life on the road. What was your biggest disaster while touring, and how did you fix it?

“I’ve weathered broken headstocks, fried pickups, stagedivers breaking my pedals, guitars cutting out and stacks going down. I’ve been knocked out, banged up and I’ve run out of Seagram’s. All that stuff is cool – I can deal with it. But the top thing that’s tooled me, the worst thing? Food poisoning.

“I got food poisoning in Venezuela, and it sucked! I couldn’t do anything for two weeks but shit and sweat. And how to cure it? Stay in bed.”

What are five things needed to survive on the road?

“Beer, Taco Bell, joints, whiskey, a Walkman, and a little acid for long bus trips.”

Places to avoid?

“Venezuela. We got there and found out that we were supposed to play this baseball field that was crawling with bats, snakes and huge blue crabs. We were going to cancel, but we were told that if we did that the government might try to plant drugs on us and arrest us. So we decided to play the show.

“That day 11 kids were treated for snake bites and that night I got the food poisoning that almost killed me. It was pretty crazy.”

What is the Pantera Philosophy?

“Go for it, go with it, but just don’t fuck with us.”

Finally, once and for all, is it Dimebag or Diamond?

“It’s whatever you want it to be.”

How about ‘Five and Dime’ Darrell?

“‘Five and Dime’ is beautiful – it may be the new one.”

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.

![Pantera - I'm Broken (Official Music Video) [4K Remaster] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/2-V8kYT1pvE/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Pantera - 5 Minutes Alone (Official Music Video) [4K Remaster] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/7m7njvwB-Ks/maxresdefault.jpg)

![▷▶Pantera - Live at Moscow Monsters of Rock [1991] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/d1qNeNctU_U/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Pantera - Walk (Official Music Video) [4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/AkFqg5wAuFk/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Pantera - Cowboys From Hell (Official Music Video) [4K Remaster] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/i97OkCXwotE/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Pantera - This Love (Official Music Video) [4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/tymWpEU8wpM/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Pantera - Goddamn Electric (2020 Terry Date Mix) [Official Audio] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/94FSvCLqcjk/maxresdefault.jpg)