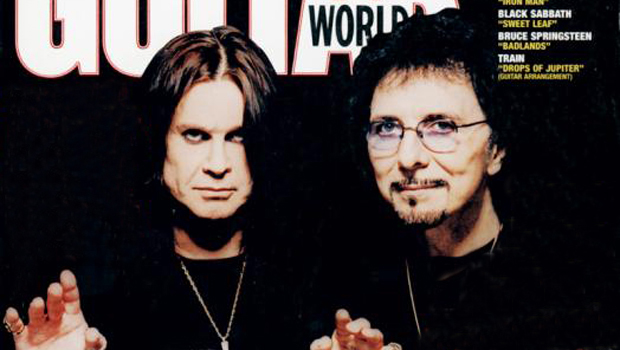

From the Archive: Original Members of Black Sabbath Look Back on 30-Plus Years of Demonic Riffing in 2001

Here's an interview with Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler and Bill Ward of Black Sabbath from the July 2001 issue of Guitar World. To see the complete cover of the Black Sabbath issue, and all the GW covers from 2001, click here.

Check out the Guitar World DVD, How to Play the Best of Black Sabbath, available now at the Guitar World Online Store.

In 1969, a long-haired band arrived out of nowhere, brandishing a heavy sound and dark vibe that was completely at odds with the "get back to the garden" idealism of the Woodstock generation.

The band's jazz-influenced drummer was almost physically incapable of playing a straight 4/4 beat, and the guitarist had lost the tips of two fret-hand digits in a freak industrial accident.

The bassist had swapped his childhood desire to become a Catholic priest for his teenage dream of becoming the next Jack Bruce, while the singer was a reformed petty criminal with a banshee wail and a propensity for drunkenly removing his trousers onstage. Their debut album opened with an anguished cry of "What is this that stands before me?" Many first-time Black Sabbath listeners undoubtedly asked themselves the same question.

Thirty-odd years down the road, Black Sabbath is still one of the most unlikely success stories in the history of rock and roll. Despite overwhelmingly negative reviews, minimal radio airplay and near-constant harassment by right-wing religious groups, the original Black Sabbath lineup of drummer Bill Ward, guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler and singer Ozzy Osbourne went on to sell millions of records.

With their ominous riffs, fuzzed-out bass lines, earth-shuddering rhythms and desolate lyrical worldview, albums like Paranoid, Master of Reality and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath charted the course for the next three decades of heavy metal-influencing a fair number of punk and grunge bands along the way -- before the original partnership finally splintered in 1979.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The tale doesn't end there, of course. Since the early Eighties, Osbourne has parlayed his "godfather of metal" image (as well as a knack for finding talented young guitarists) into tremendous solo success. Meanwhile, Iommi has soldiered on with Black Sabbath, presiding over a revolving cast that's included such august figures as Ronnie James Dio, Ian Gillan, Vinny Appice, Cozy Powell, Glenn Hughes, Eric Singer and even former Electric Light Orchestra skinsman Bev Bevan.

Geezer has returned to the Sabbath fold on several occasions, and he, Ward and Iommi have all released compelling albums of their own. But in the 20 years since Osbourne was booted out of the band, the music of the "classic" Black Sabbath lineup has grown in stature to almost mythic proportions; tickets to the group's 1998-99 reunion tour were harder to get than a seat on the space shuttle. For contemporary artists like Rob Zombie, Henry Rollins and Monster Magnet -- as well as millions of hard rockers around the globe -- nothing beats the primal power of early Black Sabbath.

The Sabs themselves agree. "I don't want to make it sound like I'm being rude to any of the other lineups or musicians," says Ward, "but there's something with Tony and Ozzy and Geezer that's just pure magic. I couldn't work with any other lineup, to be honest with you. This, to me, is like a phenomenon."

"No other band in the world could touch us when we were on,” Osbourne boasted in an interview for the Last Supper DVD, which documented Black Sabbath's historic 1997 reunion shows in their hometown of Birmingham, England -- the same shows that formed the basis for 1998's live Reunion CD. "We could give these young punks a run for their money, any time."

They'll get their chance to prove it once again at this summer's Ozzfest, where Ozzy and his mates will headline the main stage over the more youthful likes of Marilyn Manson, Slipknot, Papa Roach, Linkin Park and Crazy Town. Also slated for this summer is the theatrical release of We Sold Our Souls for Rock and Roll, a feature-length Ozzfest documentary by filmmaker Penelope Spheeris (Decline of Western Civilization, Wayne's World) that will include performances by Black Sabbath, Rob Zombie, Godsmack, Fear Factory and several other bands. In other words, summer 2001 is quickly shaping up to be the Summer of Sabbath: never before has their influence been more pervasive, or their presence more welcome.

"It's nice that, 30-odd years on, what we were doing turned out to be right," laughs Iommi. "Especially after everyone said, 'Oh, they'll never make it!'"

To say that Black Sabbath was once grotesquely unfashionable is to say that Michael Jackson seems a bit odd: it's a severe understatement of the case. "The critics hated us from day one," Butler remembers. "We actually stopped doing press at one point," adds Iommi, "because we'd get slagged either way, and it wasn't worth it." Village Voice music critic Robert Christgau panned the band's debut album as "the worst of the counterculture on a plastic platter," while the usually insightful Frank Zappa once described Sabbath as “the epitome of heavy metal sickness." But even before the Platinum records and the sold-out world tours, Black Sabbath was a lightning rod for negative reaction. "They even used to take the piss out of our accents in England," Butler says. "They slagged us off because we weren't from London or Liverpool or Manchester."

Rather than hail from one of England's three hip music centers, the four original members of Black Sabbath had the relative misfortune to grow up in Aston, a grimy industrial suburb of Birmingham. Though Birmingham did produce a few excellent Sixties bands of note, including the Move and the Moody Blues, working-class Brummies demanded covers of Motown hits and blues classics from their club bands; original compositions were simply not welcome. "You pretty much ruled the roost if you played soul," says Iommi. "When we first started playing blues, it was very difficult to get a gig, because there weren't that many places to play."

Formed from the remnants of two local bands, the Rare Breed (which featured Osbourne on vocals and Butler on rhythm guitar) and Mythology (which included Iommi and Ward), Black Sabbath began life in 1968 as the oddly named, six-member Polka Tulk Blues Band before slimming down to a quartet called Earth. No demos or live tapes of Earth exist, and generations of Sabbath fans have speculated at length on the band's sound. To hear. Butler tell it, Earth and Sabbath were two entirely different animals.

"We were just a straight blues band then," he insists. "That's the only way the clubs would have us. We'd basically play some blues and some heavier stuff, like Cream. And eventually the heavier stuff took over!"

Originally a Beatles fan who'd studiously copied John Lennon's rhythm licks, Butler switched over to bass when power trios like Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience arrived on the British music scene. "Cream became me favorite band," he says. "I loved the way Jack Bruce played his bass. His playing was so strong, he totally did away with the need for a rhythm guitar. He took the bass in a totally different direction, and I thought, Yeah, that's what I want to do!"

Butler's move to bass freed the band of its need for tightly structured arrangements, allowing them more room to play off each other. For Ward, especially, this came as a welcome development. "I found very early on that I lacked the ability to be able to play as a timekeeper," he laughs. "I have a really tough time even thinking in those terms. When I hear Tony play a piece of music, for example, I answer back. I actually do accompany him, but in way that complements what he does. l'd just be bored playing a straight rhythm."

Profoundly influenced by such disparate artists as Jimi Hendrix, Gypsy jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt and Hank Marvin of British instrumental combo the Shadows, Tony lommi was an inveterate tinkerer who, by his own admission, once rendered a mid-Sixties Fender Strat completely worthless by burying its sunburst finish under white spray paint. Iommi's mania for invention would eventually serve him well, however.

After accidentally chopping off the ends of his right middle and index fingers during his day job at a sheet metal factory at the age of 18, the left-handed Iommi molded some replacement fingertips from a melted plastic bottle of dish soap, then affixed the prosthetics with leather strips for added grip. Unable to feel with his two middle digits, Iommi began stringing his guitar with extra-light strings, tuning them down a half-step for easier bending.

Relying heavily on his index and pinkie fingers, he developed a flair for playing fifths-which, combined with a cranked amplifier and his Heath Robertson Rangemaster (an early distortion pedal), created the template for the menacing Sabbath sound.

According to Osbourne, Iommi was also the one who suggested that the band take its music in a darker direction. "He came to rehearsal one day and said, 'Isn't it funny how people pay money to watch horror films -- why don't we start playing scary music?' And then he came up with that 'Black Sabbath' riff, which was the scariest riff I've ever heard in my life!"

"Well, I just wanted to create something that was startling, something that would really take you aback," Iommi explains. "Something where you'd go, 'Wow, what's this?' and get tingles up your spine. And I liked the idea of, you know, coming up with something a bit more powerful than, say, [the Mamas & the Papas song] 'Monday Monday.' Which I liked," he says, with a laugh, "but I wanted to do something different."

"Black Sabbath," Earth's first musical excursion into the nether realms, took its name from a Boris Karloff movie, though its lyrics were inspired by a terrifying incident much closer to home. Having borrowed a 16th century tome of black magic from Osbourne one afternoon, Butler awoke that night to find a black shape staring balefully at him from the foot of his bed. After a few frightening moments, the figure slowly vanished into thin air. Figuring that the specter must be somehow connected to Osbourne's book, Butler ran to the shelf where he'd left it -- only to find that it, too, had disappeared.

"I was seeing all kinds of things at the time, and not through drugs," Butler reveals. "Ever since I was a kid, I'd have premonitions, and weird things would appear to me. One summer, me sister and I were staying at me grandmother's house in Dublin. We were in the house on our own, with my aunt in the other room, and we heard somebody coming down the stairs. We thought it was me mum and dad coming back, but when we ran out to look, we saw this apparition slowly coming down the stairs. We were both like, 'Aaaaah!!!' When we described it to our auntie, she said it was an old woman who used to live there, who had recently died.

"I'd had several experiences like -- that, but the one with the book was really intense, and I told Ozzy about it. It stuck in his mind, and when we started playing 'Black Sabbath,' he just came out with those lyrics. We were all into that doomy thing. It had to come out, and it eventually did in the song -- and then there was only one possible name for the band, really!"

John Michael "Ozzy" Osbourne grew up poor and easily distracted. A natural cut-up, he fared dismally in school, and his attempts to make it as a street thug were even more pathetic. After doing a prison stretch for a botched breaking-and-entering, Ozzy was convinced by his love for the Beatles to try singing for a living. Iommi, who had gone to school with Ozzy (and had beaten him up on several prior occasions), was initially leery about being in a band with him, but the singer's enthusiasm -- and the fact that he came complete with his own P.A. system-eventually won the guitarist over.

Osbourne's performances with Earth may be lost to the mists of time, but there's no question that he was the ideal frontman for the original Black Sabbath. Against the bludgeoning onslaught of Sabbath's music, Ozzy worked his limited vocal range and hyperactive demeanor for all they were worth, bringing a much-needed sense of humanity to Black Sabbath's music. On record, Osbourne came off not like a high satanic priest or a metallic sex god, but as a regular shmoe who'd unwittingly become embroiled in situations far more complex and frightening than he could have ever imagined. Having been raised in the shadow of the atomic bomb and the escalating war in Vietnam, a large segment of the rock audience could certainly relate.

Onstage, Osbourne was a demented cheerleader, a wobbling dervish who thought nothing of mooning a crowd, or-in one famous case where the band was joined mid-set by a troupe of Belgian strippers -- whipping out his member to enjoy a drunken wank. Offstage, his ability to find (or manufacture) trouble quickly became legendary. Iommi often had to lock him in a backstage closet or dressing room before a show, just to ensure that the singer would still be around when it was time to take the stage. On other occasions, a passed-out Osbourne would have to be retrieved from behind a locked hotel room door by Iommi and various members of the road crew.

"I've always looked at it like, 'Some body's got to do it,' " Iommi says of his Oz-catching days. "And, unfortunately, it was me! Events like that probably happened in every other band -- only more so in our band, because of the people in it."

Butler agrees. "I think Tony was the great leveler of the band," he laughs. "He sort of steered the ship in the right direction. If there were four Ozzys, we never would've gotten anywhere!"

Butler's all-time favorite Ozzy anecdote dates from 1977, when Sabbath was touring Europe behind the Technical Ecstacy album. "We were in this hotel restaurant in Germany," he recalls. "We were drinking these liter mugs of ultra-strong German beer, so Ozzy was absolutely legless by the time we'd finished our lunch. We'd gone in there around noon; by four o'clock, Ozzy couldn't get up anymore, so he just started pissing under the table. We were like, 'Oh, come on, let's go if he's going to start all this!' So we got him up and dragged him to the elevators.

"Just as we got there, this busload of American tourists came in. They were all old people, in their sixties and seventies, and they were all being checked in by their tour guide. Ozzy gets in the elevator, and just as the doors are closing I see him starting to take down his trousers. I was like, 'Aw, no!' And then, instead of going up, the elevator goes down. By the time it comes back, all these old pensioners have been checked in and are waiting for the lift. It comes back up from the basement, the doors open, and there's Ozzy, going 'Unnngh!' with a great big pile behind him! He looks up, and everybody's like [gasps in horror]! Nobody said anything; the doors just closed, and he went up!"

"The great elevators of Europe had yet to be defiled in late 1969, when Black Sabbath entered the studio to record its self-titled debut album. The owner of a Birmingham blues club, manager Jim Simpson scored the band a deal with Fontana Records. Unconvinced of its new signing's commercial potential, the label decreed that the band's first single would be a cover of "Evil Woman (Don't Play Your Games with Me)," already a U.S. Top 20 hit for Crow, a blues-rock band from Minneapolis. When that release (mercifully) tanked, Fontana fobbed Sabbath off onto Vertigo, an up-and-coming progressive rock label. Recorded in less than a day, with then-unknown producer Rodger Bain at the controls, Black Sabbath shocked the English record industry by hurtling into the U.K. Top 10. Raw, bluesy and devastatingly heavy, Black Sabbath served notice that a new day was dawning for hard rock.

"I think that first album is just absolutely incredible," says Ward. "It's naive, and there's an absolute sense of unity -- it's not contrived in any way, shape or form. We weren't old enough to be clever. I love all of it, including all of its mistakes!"

"It was recorded very quick," Iommi remembers. "We wrote it over a period of months in Switzerland and Germany. We would play this club in Switzerland where we'd do five to seven spots a day -- play three quarters of an hour, take a fifteen-minute break, then play another three quarters of an hour, and so on. We had just about enough songs for one set. So we had to start making things up, and it was a great experience for us, because we used to jam, and all sorts of ideas came out of it." (When Iommi's painted Strat broke down after recording "Wicked World," he tracked the rest of the album using his spare Gibson SG. Since then, the SG has been his guitar of choice.)

On the strength of newly minted classics like "Black Sabbath," "The Wizard" and "N.I.B.," Black Sabbath (released in the States on Warner Bros.) soon made the Top 25 on the U.S. album charts as well, though the band quickly acquired as many detractors as they had fans. Rumors that Sabbath were satanically inclined were fanned by the record company's inclusion of an inverted cross on the album's inner sleeve, not to mention the line, "My name is Lucifer/Please take my hand," from "N.I.B."

" 'N.I.B.' is taking the piss out of the devil," explains Butler, who wrote the song's lyrics. "I can't just compose a straight love song, so it's like, 'Fine! I'll make the devil fall in love!' If you take the Satan out of it, it's just about this guy who falls in love. And he comes up with all the cliches, like he can give you the moon and the stars -- but he actually can! But a lot of people missed the point."

Butler, who grew up "a severe Catholic" and once seriously considered joining the priesthood, has spent the better part of his career trying to clear up the satanic misconceptions about Black Sabbath, but to little avail. "It's the same with the people that go on about Marilyn Manson," he says. "They never want to actually listen to the lyrics -- well, our lyrics, at least. They'd rather take it the wrong way, just because of the name of the band. I've done interviews with Christian papers where, if I'm talking about how much I respect Jesus, they'll say, 'But you can't possibly respect Jesus! You wouldn't be in a rock band if you did!'"

Emboldened by Black Sabbath's unexpected success, Vertigo rushed the band into the studio to record a follow-up. ''A lot of the Paranoid album was written around the time of Black Sabbath," Butler remembers. "Basically, we refined -- well, we didn't even really refine it! We just did the same thing as the first album in two days, live in the studio." Originally titled War Pigs, the album took its final, record company-mandated name from a last-minute inclusion. "We wrote 'Paranoid' as an afterthought, really, because we needed a three-minute filler for the album," Butler says. "Rodger Bain said, 'Just a minute! We need one more song!' Tony came up with the riff; I quickly did the lyrics and Ozzy was reading them as he was singing, and that's how it got done."

A two-minute, fifty-second blast of pure white boy angst, "Paranoid" was so good that even radio couldn't ignore it; the song hit No.4 on the U.K. singles charts and became an FM radio staple in the States. Tighter, slicker and even more apocalyptic than its predecessor, Paranoid is still Black Sabbath's best-selling album of all time, thanks to such immortal anthems as "War Pigs," "Iron Man" and "Electric Funeral." Adhering to the same live-in-the-studio formula was 1971's excellent Master of Reality, the band's third album in 19 months. By this point, Sabbath's schedule was so hectic that none of the band members can recall much about recording tracks like "Sweet Leaf," "Children of the Grave" and "Into the Void."

"I do remember writing 'Sweet Leaf' in the studio," Butler offers. "I'd just come back from Dublin, and they'd had these cigarettes called Sweet Afton, which you could get only in Ireland. We were going, 'What could we write about?' I took out this cigarette packet, and as you open it, it's got on the lid, 'The Sweetest Leaf You Can Buy!' And I was like, 'Ah, Sweet Leaf!'"

After three million-selling Black Sabbath albums, the band was finally awarded sufficient record company funds to allow a more multi-tracked approach to recording. Released in 1972, Vol. 4 was waxed at L.A.'s Record Plant, produced by the band with manager Patrick Meehan (who had replaced Jim Simpson after Black Sabbath took off). The copious amounts of cocaine that assisted them made its presence felt in such stunning new songs as "Snowblind," "Supernaut" and the desolate comedown ballad "Changes."

"Yeah, the cocaine had set in," laughs Butler. "We went out to L.A. and got into a totally different lifestyle. Half the budget went on the coke and the other half went to seeing how long we could stay in the studio. But it was a good time. We rented a house in Bel-Air and the debauchery up there was just unbelievable. Somehow, out of that came Vol. 4!"

"Yes, Vol. 4 is a great album," Ward adds. "But listening back to it now, I can see a turning point for me, where the alcohol and drugs had stopped being fun."

Ward's bandmates would eventually reach the same substance saturation point, though it would take the others a while longer to do so. "Sabbath Bloody Sabbath was our last coke-inspired album," says Butler. "We were still doing coke after that, but it was horrible; it had turned 'round on us by then, and was starting to kill us."

Considered by many to be Sabbath's finest hour, 1973's Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (which included such gems as "Spiral Architect," "Killing Yourself to Live" and the jaw-dropping title track) had a difficult birth.

Returning to the scene of Vol. 4, the band found L.A. to be suddenly less conducive to creativity than they'd remembered. "We came back, we rented the same house, same studio," says Iommi. "But we weren't writing anything, because we were partying too much. We finally said, 'This isn't working,' and went back to England very disappointed. It was a bit frightening, actually; I didn't know how to handle a writer's block, because I'd never had one up to that point."

"We almost thought that we were finished as a band," Butler admits. "We rented this castle in Wales to rehearse in. There were loads of weird things going on in that place -- a lot of ghosts -- but it was a good atmosphere for us. Once Tony come out with the initial riff for 'Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,' we went, 'We're baaaack!'" He laughs. "It got us rolling again, and we stayed in England and made the album."

But if the making of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath felt like pulling teeth, it was a veritable cakewalk compared to the sessions for 1975's Sabotage. The album nearly sank in a sea of lawsuits, and the litigious atmosphere was reflected in angry tracks like "The Writ," "Megalomania" and "Hole in the Sky." "We were in the studio for nearly 12 months," Butler remembers. "Around the time of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, we'd found out that we were being ripped off by our management and our record company. So, much of the time, when we weren't onstage or in the studio, we were in lawyers' offices trying to get out of all our contracts. We were literally in the studio, trying to record, and we'd be signing all these affidavits and everything. That's why we called it Sabotage -- because we felt that the whole process was just being totally sabotaged by all these people ripping us off."

Exhausted by various legal battles, not to mention years of touring and a steady intake of chemicals, Black Sabbath repaired to Miami for the making of Technical Ecstacy. The sessions proved extremely relaxing for everyone except Iommi, who was left to oversee the production while the others sunned themselves on the beach. Perhaps the least-loved effort of the original Sabbath lineup, the album saw the band trying to stretch its sound in several different directions, none of them exceptionally successful. "Rock 'N' Roll Doctor" sounded like a bad Kiss imitation, while Ward even took the lead vocals for "It's All Right," a sub-par Paul McCartney-style pop ballad.

"That was the 'beginning of the end' album, that one,'' laughs Butler. "We were managing ourselves because we couldn't trust anybody. Everybody was trying to rip us off, including the lawyers that we'd hired to get us out of our legal mess. It was really just getting to us around then, and we didn't know what we were doing. And obviously, the music was suffering; you could just feel the whole thing falling apart."

In fact, things would disintegrate completely before the four musicians reconvened to cut Never Say Die, their final studio album together. Osbourne left the band to deal with his father's death, and Butler also left for a short time. A Black Sabbath consisting of Iommi, Butler, Ward and former Savoy Brown vocalist Dave Walker actually performed live on BBC-TV in January 1978, before Osbourne decided to give the band another go.

"Never Say Die, now, that was a pain,'' remembers Iommi. "We were going through a funny period. Ozzy left, we'd got another singer, wrote some songs with that other singer, and then Ozzy came back just a few days before we were leaving to go into the studio to record the album. But he wouldn't sing any of the songs that we had written, so we had to write a complete other album, really. I booked a studio in Toronto, and we had to find some place to rehearse. So we had this cinema that we'd go into at 10 o'clock in the morning, and it was freezing cold; it was in the heart of the winter there, really awful. We'd be there, trying to write a track that day to record that night."

The band still got up to its usual mischief during the sessions -- at one point, Iommi accidentally set Ward on fire, sending him to the hospital with third-degree burns on his arms and legs -- but it was obvious to most of the participants that the thrill was finally gone.

"Never Say Die was a patch-up kind of an album,'' Butler admits. "We came back together not really willingly, but because we couldn't think of anything else to do!" he says, laughing. "People didn't realize that it was sort of tongue-in-cheek, the Never Say Die thing. Because we knew that was it; we just knew that it was never going to happen again. We did this 10th anniversary tour with Van Halen in 1978, and everybody's going, 'Here's to another 10 years!' And I'm going, [rolls eyes] 'Yeah, sure!'"

In fact, the band did attempt to make one more record in L.A., but Osbourne simply wasn't up to the task. "I was stoned all the time, and so I didn't really appreciate what was going on around me," he recounted in 1998. "I was into sex, drugs and rock and roll, and the rock and roll was paying for my sex and drugs. I should be dead. We all should be fucking dead. We were fucking abusing motherfuckers, man!"

"We were working on what turned out to be the Heaven and Hell album [Sabbath's first of two studio albums with Ronnie James Dio], and it just really wasn't happening," remembers Iommi. "I don't think any of us were in a good state at the time, but he was probably the worst. It just wasn't working at the time with Ozzy, and we just had to make a decision."

The decision to fire Ozzy left the singer feeling, by his own admission, "very pissed off and bitter"; meanwhile, his bandmates struggled (largely unsuccessfully) to fill the artistic and emotional void he left behind. Beset by mental illness brought on by years of drug and alcohol abuse, Ward left and rejoined the band several times in the early Eighties, finally bailing for good in 1984 along with Butler, who would return in the mid Nineties. Iommi's decision to continue touring and recording under the Black Sabbath name caused some friction with his former bandmates, though the guitarist has always staunchly defended his actions.

And yet, despite the angry words, the lawsuits, the solo careers, the all-too-brief reunions (like Live Aid in 1985), the health problems (Ward suffered a heart attack in 1999) and all the other frustrating events of the past 20 years, the legacy of the original Sabbath lineup still endures. "I think it's timeless; it's ageless," says Ward of the music. ''And the subject matter stands as true today as it did 30 years ago."

Now, with friendships rekindled, old wounds patched and hurt feelings finally salved, rumors of a new Black Sabbath studio album have started to fly. For their part, the Sabs remain noncommittal, perhaps understandably so. "We've been writing a few things, and we're just going to see how it goes," Butler explains. "The one thing we don't want to do at this time is record an album just for the sake of getting a large advance from the record company. I mean, we've got a big reputation to follow. We don't want to kill it by putting out a bad album."

“I said, ‘Let’s get Hendrix to play on it.’ His manager said, ‘Jimi’s playing shows back-to-back.’ So we got Jimmy Page”: The hit ’60s single that was supposed to feature Jimi Hendrix… but ended up with Jimmy Page

“It was tour, tour, tour. I had this moment where I was like, ‘What do I even want out of music?’”: Yvette Young’s fretboard wizardry was a wake-up call for modern guitar playing – but with her latest pivot, she’s making music to help emo kids go to sleep

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)