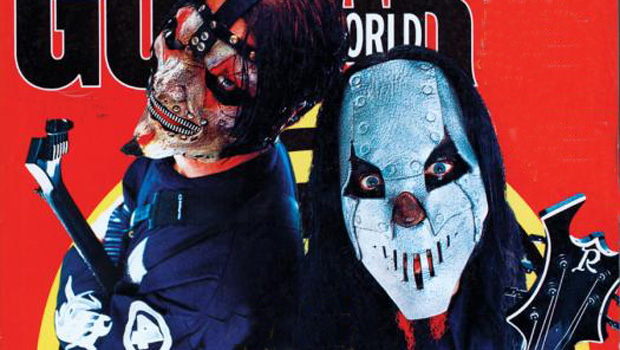

From the Archive: Mick Thomson, Corey Taylor, Paul Grey and Jim Root Discuss the Dark, Brutal World of Slipknot

Here's an interview with Mick Thomson (7), Corey Taylor (8), Paul Grey (2) and Jim Root (4) of Slipknot from the June 2000 issue of Guitar World.To see the cover, and all the GW covers from 2000, click here.

As the lights go down in New York City's Roxy music theater, a sinister, disembodied voice repeats hypnotically, over and over, a digital sample locked into an endless loop: "The whole thing I think is sick/The whole thing I think is sick/The whole thing I think is sick... "

On the main floor, a crowd of teenagers -- most of them young, male and riled up by opening acts Primer 55 and Biohazard -- surges back and forth as mosh pits begin to pockmark the floor. The looped phrase doesn't have a beat, but the crowd is beyond caring about such minor details. They want action. They want blood.

They get it soon enough. Colored lights begin to spin crazily, and smoke billows from the stage, which is strewn with numerous amps, three drum kits, a DJ coffin and a sampler. A roar erupts from the crowd as nine men in masks and coveralls -- each emblazoned with an Orwellian barcode and the letter "S" -- take the stage. With nothing to identify them but their slasher-film masks and numeric identifiers -- the numbers 0 through 8--the men on the stage look like the members of a Roger Corman death squad. They pace back and forth, flipping off the crowd and staring down the hard-asses too tough to give into the moment's unhinged energy.

Finally, a man in a mask sprouting ragged blond dreadlocks steps up to a microphone.

"New York City," bellows 8, "I want to see you go off like a motherfuckin' act of God!"

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What follows can only be described as an act of musical violence. For the next hour and a half, guitarists 4 and 7 slam out riff after riff, while polyrhythmic, industrial-tribal beats fire off with the regularity of a military exercise. Out on the floor, the sea of bodies boils over as one kid after another body-slams his neighbor, setting off a domino effect that ripples through the crowd in waves. Things are only slightly calmer onstage.

At one point, 6 -- one of the group's two percussionists and the wearer of the grinning clown mask-climbs on top of his rig. Gyrating wildly, he suddenly slips, slamming his face directly into a drum rim. Blood spurts from an eyehole, a strangely beautiful arc of red that glitters in the stage lights. Recovering quickly, 6 keeps playing. He even sticks around after the show to sign autographs, before being dragged off to the hospital for what will be more than 14 stitches.

"That was nothing," 4 says casually afterward. "Once, our DJ lit himself on fire. One of the percussion kegs was burning in the middle of the stage. He had the can of lighter fluid, and I guess he got some on his coveralls."

His zipper-mouthed jester mask seems to grin at the memory.

"But like I always say, in Slipknot, what doesn't kill you only makes you stronger."

Few groups in recent memory have seemed so bent on self-annihilation as Slipknot. Since emerging from the corn-infested depths of Des Moines, Iowa, the group has been on a conquer-or-die mission to put the final nail in the coffin of corporate-packaged, radio-friendly rock.

America received its first widespread exposure to Slipknot's anarchy when the group, then virtually unknown, performed on the second stage at OZZfest '99, confounding people with its "wall of noise" approach to music. Today, however, after selling more than 500,000 copies of its current self-titled album and headlining tours all over the world (even playing a date on Late Night with Conan O'Brien), Slipknot has proven that there is a growing contingency for its brand of collaborative, multi-leveled metal. AB the group prepares to enter the studio to record its follow-up album, Slipknot seems to be on the verge of exploding in ways even its members never anticipated.

"It's like this," says 8, the group's vocalist. "Slipknot is a big scary monster, and we're losing control of it. We're reaching the point where we don't know what it's going to do or who it's going to do it to. And that's just how we want it to be. Because we're so sick and tired of these pussy-assed bands that suck the corporate money-cock and spit out so-called music. Now we're going to do it our way."

Ministry's Al Jourgensen once sang that "every day is Halloween," and for Slipknot, that's certainly true. More than a band, Slipknot is an image, a distinction it shares, at least on the surface, with bands like Kiss and Marilyn Manson. But who's to say that Slipknot's masks and coveralls aren't just another ploy to divest gullible 15-year-old malcontents -- looking to rebel against their parents, their schools or their otherwise homogenous lives -- of their hard-earned allowances?

"Of course our look gets us noticed," says 7, the band's lead guitarist. "But it's not as contrived as all that. We started wearing masks and coveralls before we ever thought we'd have any success, before we were officially Slipknot. We would have worn them even if we never left our practice space."

For Slipknot, the masks are shields for the members to hide behind, as well as windows into each player's personality. "With the mask, you can be the self you can't be under normal circumstances," says 7. "In real life, I'm pretty shy and introverted. But just because I'm sitting quietly in a crowd doesn't mean that I don't want to jump up and smash heads in with a baseball bat. So I take that thing that's inside me and bring it out when I'm onstage. The mask lets me do that." 8 backs him up.

"I've always felt that the mask is what I look like on the inside. It's the face of my pain and anger. "Plus," he adds with a rueful grin, "my mask hurts. It's tight, and it's hot behind it. But after a few minutes, the pain goes away. The pain is like a switch: it turns me into what I am onstage -- the voice of the monster. When you put nine lunatics onstage, you're not getting Raggedy Ann."

Nor are you getting much in the way of humanity. For an audience member, Slipknot becomes a collection of automatons, making it easy for fans to imbue the group with their own fears and hates.

"We're almost like comic book characters -- I won't deny it," says 7. "In many ways, we become -- at least to these kids -- superhuman. At the same time, we don't have to deal with all the rock-star bullshit that goes along with this business. I don't worry about makeup except for the black stuff I wear under the mask; there's no prettying up for photographers. We're the 'anti-image,' and that's something else that the kids can relate to. Everyone, when they're 15 or so, feels like an outcast. None of us look like the supermodels being shoved down the public's throats. We bring that to the very front. We push your face in it."

Of course, a bunch of guys running around in Halloween masks and coveralls tend to stand out in a crowd, and not always for the better. On one occasion, while on their way to an in-store signing, the band members pulled into a shopping mall parking lot to change into their costumes. “All of a sudden, these cops show up," says 4. "It turns out we were right in front of a jewelry store, and the security guard thought we were there to rob the place. At one point, we were sitting in the van, and the cops were all around us, with their guns drawn. 6 asked if he could take off his clown mask. One of the cops said, 'Sure. If you have a gun, I'll just shoot you through the door.'

"It was tense for a while, but we sorted it out. We even signed some autographs for them."

Des Moines, Iowa, isn't exactly a hotbed for successful music acts. Even the guys from Slipknot can't think of one band that's managed to make it out of the city.

"No band from Des Moines has ever done a goddamned thing," says 7. "If it weren't for Slipknot, I'd probably be up in a clock tower with a rifle right now. This band saved us all."

At the very least, it saved them from years of dead-end club dates and college frat parties. Slipknot formed five years ago when the band's members -- lead guitarist Mick Thomson (7), guitarist Jim Root (4), bassist Paul Gray (2), vocalist Corey Taylor (8), DJ Sid Wilson (0), sampling/media mixer Craig Jones (5), percussionists Chris Fehn (3) and Shawn Crahan (6) and drummer Joey Jordison (1) -- gathered to jam out some music.

"We were all friends and just decided to play together," Thomson explains. "We never thought it would go further than that. Everyone always talks about the 'rock and roll dream.' But I never had that dream -- I'm not delusional. I've always felt like only the acts producing dog shit ever make it to the top. Those of us slogging it out in the trenches -- especially those with talent -- never even get heard.''

The Des Moines metal scene was an incestuous musical environment to say the least. The members of Slipknot had all been involved in various projects together. As their individual bands fell apart, the like-minded musicians were soon drawn together by their common desire to try something new.

"Mick and I played in a death metal band before Slipknot,'' says Gray. "And Shawn and I used to do some jamming together. Back then -- almost seven years ago -- we were a lot more percussion oriented. Over time, our sound evolved into what it is today."

For Taylor, joining the band was almost preordained. Des Moines' music scene was split down the middle, with Slipknot drawing half the fans while Taylor's band, Stone Sour, pulled in the rest. "I was at the very first Slipknot show, when they had their original singer," says Taylor. "I knew I would sing for them; it was only a matter of time." When Slipknot's original singer departed, Taylor auditioned to replace him and brought with him lyrics to a song the group had written. "That was when we knew it would work," says Taylor. When Slipknot needed a second guitarist, it was Taylor who called in his friend Root to take the job.

Practically nothing in Slipknot's evolution was the result of carefully considered thinking. Even the decision to wear masks and coveralls -- outfits that are critical to the group's image and a badge of its nonconformist stance -- happened by chance. "We were practicing one evening, years ago, and Shawn came in and put on this clown mask -- just started jamming with it on," says Gray. "It was creepy as fuck, but also very cool." Shortly after, each member began to create his own mask. "It just seemed like the most natural thing in the world at the time."

Each member's mask developed in its own way. For Root, it was simply a matter of buying a jester's mask, cutting it up, sewing it back together, stitching on a zippered mouth and riveting on some straps. Taylor, on the other hand, started out wearing the slashed-up "face" from a crash test dummy, his blond dreadlocks sticking out of holes in the top. "But that mask started to melt on me during OZZfest," he says. "So I decided to shave my head and glue my dreads onto the new mask."

While the decision to wear masks came quickly, the coveralls took a little longer. "Mick once wore a Little Bo Peep dress," says Root. "Corey wore a priest's outfit and Shawn wore coveralls spattered in paint. I don't remember who thought of it, but we decided that the coveralls would bring a tribal sense to the band that we needed."

Last of all were the numbers. "We each just fell into our own number," says Taylor. "No one fought over a number; no one even wanted the same number. It was perfect."

In 1996, Slipknot released the self-produced album Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat. Despite the group's cynical view of the music industry, the album attracted the attention of several major labels and industry insiders, like producer Ross Robinson, whose clients include Limp Bizkit and Korn. Through his imprint, I Am Records, Robinson brought Slipknot to Roadrunner Records, then took the group into Indigo Ranch Studios in Los Angeles to record the Slipknot album.

"Ross really kicked our ass during those sessions," says Thomson. "We're a tough band full of messed up, aggressive people. But he whipped us into shape. Just listen to the end result."

With the album's release, Slipknot launched into a heavy touring schedule, the highlight of which came at last summer's OZZfest. Thomson believes the group's success is in part due to the willingness of mainstream audiences to embrace harder music. He credits bands like the Deftones and, in particular, Korn with preparing radio stations and their listeners for the aural brutality that makes up a typical Slipknot track.

"I'm not really into Korn," says the guitarist. "But look at it this way: I used to watch lots of gore movies, lots of 'true death' videos. And at first, sure, I was disturbed by what I saw. But after a while, I became numb to it. With hard music, it's the same way. People listened to Korn, and now they want something even harder. It's like a drug."

Slipknot's members have themselves developed a more mature approach to their craft. "We've realized that you don't need to have the 'Bon Jovi' stage lighting.to have a good show," says Taylor. "You can just get up there and do what you do, the way you do it, and if you're honest with yourself and with your audience, they will react to you."

"The most important thing is that we connect with our audience," adds Thomson. "We'll fuck with them, and then I'll find some punk in the crowd who's staring at me and giving me the finger and shit. I'll just give him a look and then see how quickly that finger drops. Because -- and I've seen it again and again -- the bands that can't connect to their audiences are the bands that you eventually see on Where Are They Now?"

But while so much emphasis is placed on Slipknot's outfits and stage act, the fact that its members are also musicians tends to get overlooked, not only by the media but even by the fans.

“Man, I’m a born shredder,” says Thomson, with unabashed pride. "Yngwie Malmsteen is a fuckin' god. I could listen to his shit for hours. You can hear every single note he plays. Sure, anyone can be fast and sloppy, but he just nails it. You can even hear the way his pick hits the strings on his guitar. That's good."

Thomson has been playing guitar for 16 years, and prior to Slipknot's success, was a guitar instructor. "People think our music is so simple to play, and I have to laugh," he says. "Sure, it may sound straightforward, but a lot of it is pretty... strange. It's a bit more complicated than people assume."

But simple or not, the songs take precedence over guitar histrionics. "I'd love to work some shred stuff into our music," says Thomson. "My death metal band was full of really technical guitar work. But the fact is, it never felt right for these songs. And the song has got to take priority. Too many guitarists forgot about that in the Eighties. The key is to be selective about how you use it." As an example, he points to a riff from his death metal days that he modified and stuck in the middle of "Surfacing." "That's as close to shredding as I get on this album," says Thomson. "But I think it works really well. Besides, there's always our next album."

Like every aspect of Slipknot, songwriting is a collaborative and ever-evolving process. Typically, the "core group" -- Thomson, Root, Jordison and Gray -- will work out a song's primary structure. Later, when the band gets together for rehearsal, elements such as percussion, DJ beats or sampled material will be added as the group feels they are necessary. ''Just because we have a DJ doesn't mean that he plays on every song," says Thomson. "If he's needed, great. If not, we don't force it. But we're willing to try anything out before it gets rejected."

Often, songs develop in the course of jamming or just fooling around with a riff. " 'Spit It Out' was that way," acknowledges Thomson, "whereas 'Eyeless' started with a beat that Sid was kicking out from his turntables. I started playing that weird little noise line over it, and the next thing we knew, the song was written."

After the music is completed, Taylor works on lyrics. Often, they suggest the perspective of someone scarred by life, yet looking for a way to heal: "Insane/Am I the only muthafucker with a brain/I'm hearing voices but all they do is complain," Taylor sings in "Eyeless," while in "Purity" he commands, "Put me in a homemade cellar/Put me in a hole for shelter/Someone hear me please, all I see is hate/I can hardly breathe and I can hardly take it."

"I don't talk about a lot of stuff except through my lyrics," Taylor sighs. "They come from a place I don't really like to go. But I do go there, every night we play. And because I do, I don't walk into a McDonald's with a machine gun and mow down a bunch of people. Once I take the stage -- I don't care if it's the first time or the thousandth -- my heart is lifted and all the pain goes away."

Now, as Slipknot prepares to enter the studio again, its members agree that they have to up the ante. There's no room for passivity or complacency in Slipknot's world view. "If anything," says Thomson, "this album is going to be even harder, even more technical than the last. The first time, we knew that we had to win fans, to prove that we had what it takes. For this album, it's about staying around. It's showing that we're no fluke."

"I want everyone who hears this next album to say to themselves, 'Jesus Christ, that really bothers me,'" says Taylor. "I want it to be so profound and so justified that people will shut their fucking mouths forever about the sophomore jinx -- to us, that's just another sacred cow to kick in the face.

"No other band is stepping up and making music a priority. So we have to go and do it. If we ever had a message, it would be that the music is first. Because you can't stop this -- it's begun. It's bigger than us. And it's out of our hands."

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“Such a rare piece”: Dave Navarro has chosen the guitar he’s using to record his first post-Jane’s Addiction material – and it’s a historic build

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)