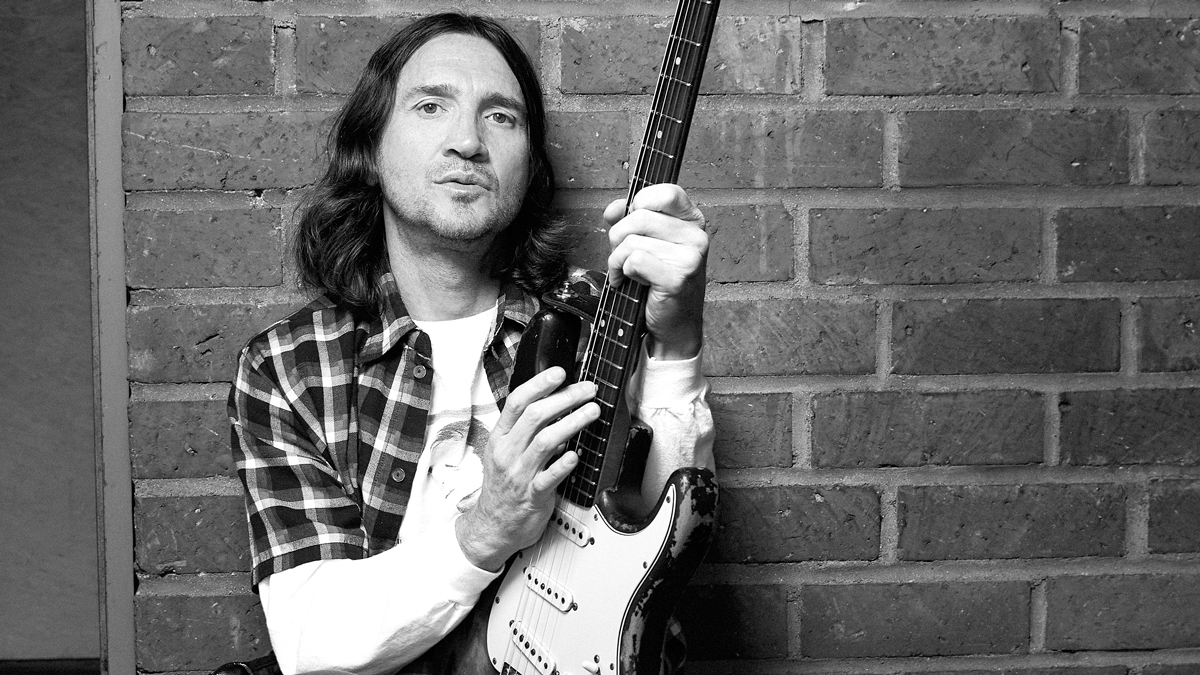

John Frusciante: “There’s an appreciation of the chemistry I can’t say I had last time – when you get so used to something, you sometimes take things for granted”

One of the most influential guitarists of his generation on what prompted his return to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and how a deep-rooted playing philosophy fueled their explosive comeback album, Unlimited Love

In the end, it was a simple reason that led John Frusciante to return to the Red Hot Chili Peppers. “I really wanted that challenge of trying to work in a democratic band with people that I respect and people that I have a chemistry with,” he says.

“I felt that to move forward as a soul and as a human being, I had to accept that challenge. I felt that it would be good for me to try to work harmoniously with them, and not have my ego be the thing that was driving me forward, but to have love and respect for them. That was the thing: to try to be a part of a whole.”

Frusciante is talking to Total Guitar from his home in Los Angeles, the city where the Red Hot Chili Peppers formed back in 1983. With his long hair unkempt under a wooly beanie, his face unshaven, wearing black-rimmed glasses and his lean frame clad in a loose-fitting yellow t-shirt and green jacket, the guitarist looks pretty much the same as he did 16 years ago, when double album Stadium Arcadium gave the band its first-ever US number one.

But it was in the wake of that album’s success that John quit the band – the second time he had done so, having previously bailed in 1992, both exits prompted by his discomfort with the pressures of fame.

Following his departure in 2009, the Chili Peppers went on to release two albums with another prodigious California guitarist, Josh Klinghoffer. Frusciante, meanwhile, pursued his love of electronic music and modular synths, in an effort to make music that stood apart from the band with which he made his name, and with entirely personal – and non-commercial – aspirations.

So it came as a surprise when the Chili Peppers issued a social media communique in late 2019 announcing Frusciante’s return, and with it, the potential for a new album – their first with John in the fold since Stadium Arcadium.

The fruits of their labour, Unlimited Love, finds the band reunited with super-producer Rick Rubin, showcasing 17 tracks that run the gamut of their collective influences, from breezy funk to progressive rock and hardcore punk.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In short, the chemistry between John, bassist Flea, drummer Chad Smith and frontman Anthony Kiedis has resurfaced intact, a musical formulation unimpacted by the decade-plus break and even a global pandemic.

Naturally, there’s a lot to talk about, and John is certainly in the mood to talk – so much so that his conversation with TG extends beyond its allotted 60 minutes to nearly two hours.

The guitarist loves to discuss the subjects closest to his heart – the art of making music, his studio secrets, the sense of anticipation ahead of the band’s return to the live stage. He is also candid about his reasons for leaving the band over a decade ago, and what ultimately brought him back to his musical brothers.

I think no one person is at fault in a situation where somebody quits a band, I’d grown enough as a person to see my side in it, as opposed to just playing the victim

“I’ve done a lot of reflection on the causes of my quitting the band the last time that I don’t think I had the mental space to be aware of at the time,” he says. “It was like, ‘I just really don’t want to do all this living in this world of fame and publicity; I just want to concentrate on making electronic music and making music just to make music, and not to make people happy, not to be successful.’ And that was just what I needed at the time.

“But I looked back and realised that with some of the personal stresses between me and other members of the band, I saw my own part of it more than I think I saw it back in 2009. And while I think no one person is at fault in a situation where somebody quits a band, I’d grown enough as a person to see my side in it, as opposed to just playing the victim.”

A new beginning

It’s hard to overstate the impact John Frusciante has had on generations of guitarists. With his sparse, feel-driven lines on the Chili Peppers’ 1991 breakthrough Blood Sugar Sex Magik, he introduced ’90s players to a wiry, exhilarating blend of funk and post‑punk.

And in his second tenure with the band, a run of three expansive, diverse, multi-million selling albums – Californication, By the Way and Stadium Arcadium – kept adventurous textures and guitar solos at the forefront of mainstream rock, at a time when pop-punk and nu-metal ruled the airwaves.

For this third phase, the reunited band took their tentative first steps in the rehearsal room. Rather than begin writing straight off the bat, they played material from the earliest Chili Peppers albums – released when John was a fan rather than a member of the band – in a bid to reconnect with the roots of the group.

Meanwhile, band members suggested covers of classic tracks – Some Other Guy by Richie Barrett, Trash by the New York Dolls, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson’s Hot Little Mama and the Kinks’ Waterloo Sunset all received a workout – which injected fresh energy into rehearsals.

“I didn’t want to feel any pressure about writing stuff, because that would have been overwhelming,” John recalls. “So for a month or two, we were just playing songs by other people, and playing really early Chili Peppers stuff. We just had a lot of fun.

“And luckily that spirit of fun ended up staying with us throughout the whole writing process, even after those songs had been phased out and replaced by going there every day being excited about the new stuff we were bringing in, or the jams that we were turning into songs.”

I felt like as long as I’m getting back into making rock music, let’s go to the roots of it

And boy, did they have a lot of songs. By the time the band hit Rubin’s Shangri-La studio in 2021, they had 45 tracks ready to go, with a further three written during the sessions. All were ultimately recorded, leaving more than enough material for a follow-up record (“I definitely feel like we saved some of the best stuff for the potential next album,” John teases). But, he adds, he never had the intention to write quite so many songs.

“You know, I was ready to stop when we had, like, 20 – I felt like that was good enough,” he laughs. “But one thing led to another and somebody or other kept encouraging me to keep bringing in more songs. So, before we knew it, we had way more songs than we’d ever written for a record before.”

For his part, Frusciante had to readjust his guitar playing to write rock music again. During his electronic music wilderness, any time with a guitar in his lap was more often spent appreciating music than composing it.

He learned every solo recorded by jazz great Charlie Christian, and took inspiration from the chord progressions in landmark ’70s albums by progressive rock legends Genesis. It helped him reconnect with his love of the instrument.

“I developed a real fan relationship with the different forms of rock music, without it having anything to do with my identity,” he explains. “So when I went back to playing in the band, I knew it would affect what I wrote.”

Accordingly, the guitarist had a vision for where he wanted to take his compositions, and it harked back to the origins of the genre he was returning to.

“I really wanted to focus on where I see the beginning of rock music in history – the rock ’n’ roll of the late-’50s, and the electric blues that took place throughout the ’40s and ’50s,” he says.

“I wanted to imagine that I was a guy coming up at the same time as The Beatles or Cream or Jimi Hendrix, to see: ‘What would I have done to embellish upon that foundation?’ I felt like as long as I’m getting back into making rock music, let’s go to the roots of it.

“I’d spent so much time on other records specifically focusing on Jimmy Page and Jimi Hendrix and Cream. Rather than do that again, I thought, ‘Let’s focus on Elvis and Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown and Freddie King and Albert King, and Buddy Holly and Gene Vincent and Ricky Nelson – and then, okay, so how would I try to do something beyond this?’”

Those plans would change shape once John began collaborating with the band. To warm up for recording each day, he would play through Jeff Beck’s classic albums Truth, Blow By Blow and Wired. But equally, he was re-immersing himself in the textural approach of Siouxsie And The Banshees’ John McGeoch, as well as Greg Ginn’s abrasive riffs in Black Flag. His approach became an amalgamation of all those influences, with a smattering of ’80s guitar heroes for good measure.

I really love guitar players like Randy Rhoads and Eddie Van Halen for the way that they could make the instrument explode through hand and whammy bar techniques

“I really love guitar players like Randy Rhoads and Eddie Van Halen for the way that they could make the instrument explode through hand and whammy bar techniques,” he says. “But I also really like the way people like Greg Ginn or Kurt Cobain play without it being so much about technique – although there are all kinds of unconventional techniques in there – but the focus is definitely a more visceral thing.

“Eventually, by the time we were recording, my concept was to find a bridge between those two conceptions of the instrument: that idea of making it explode with the electricity of the human energy that comes through the strings.

“And, also, using the full range of the instrument in terms of the types of techniques that, while Eddie Van Halen and Randy Rhoads did a lot to develop them, I see them all as being rooted in what Jeff Beck did on Blow By Blow and Wired.”

Stretching out

Ultimately, Unlimited Love became a distillation of the guitar heroics Frusciante employed on the bombastic Stadium Arcadium, sitting alongside the ambient sonics found on By the Way’s more experimental moments, all while incorporating a more overt punk influence.

His wide-ranging approach spans the anthemic alt-rock of Black Summer through to the sultry funk of Poster Child and the ferocious hardcore of These Are The Ways, which dishes out the album’s heaviest riffs – although the track’s inception was very different to the rock monster that ended up on the record.

“Before I wrote the music for These Are The Ways, I was playing along with Sparks’ album Propaganda,” John recalls. “I was just blown away by how seemingly simple but imaginative their chord progressions are.

“But once I brought it to the band, we turned it into this heavy-duty thing where the drums go from being like Keith Moon to Black Sabbath to Metallica. The end seems like a speed-metal thing to me. With the power of the band, it definitely turned into something else.”

Another stylistic left turn crops up on White Braids & Pillow Chair, a mid-tempo chord workout that ends up as a full-blown rockabilly wig-out. It was one of the first songs John brought to the table, and one of his favourites in the way it “mixes up a few things that are important to me”, blending a voice-leading progression inspired by Genesis keyboardist Tony Banks with an early-’60s surf outro.

John’s more textural approach, meanwhile, crops up on slow-burn groovers Not the One and It’s Only Natural, which combine the minimal six-string ethos of ’80s goth with techniques inspired by all-time guitar greats.

The former draws on Adrian Belew and Eddie Van Halen’s mastery of the guitar’s volume control, teamed with expansive digital delays. The latter features smatterings of backwards delay – an ’80s hallmark – on its psychedelic solo, but its deceptively simple verse atmospherics found John once again turning to Jeff Beck for inspiration.

It sounds like there’s an echo on It’s Only Natural, but that’s me with my right hand just being loud, loud, loud, softer, softer, softer, softer, softer

“It sounds like there’s an echo on It’s Only Natural,” he says, “but I’m doing that with my hands. That’s not an echo. That’s me with my right hand just being loud, loud, loud, softer, softer, softer, softer, softer.

“I had actually been doing it a lot because on Jeff Beck’s Blow By Blow there’s a song called Constipated Duck, and I think he probably actually has an echo on his guitar, but to play along with it, you have to do that: play loud, softer, softer, softer, softer, to sound like you’re matching the recording.

“Flea had come up with the idea of It’s Only Natural on piano. And then when he switched to bass, I thought that would be cool if I tried to do that kind of thing, like I’m doing on Constipated Duck, but make it a part of the song.”

Old friends

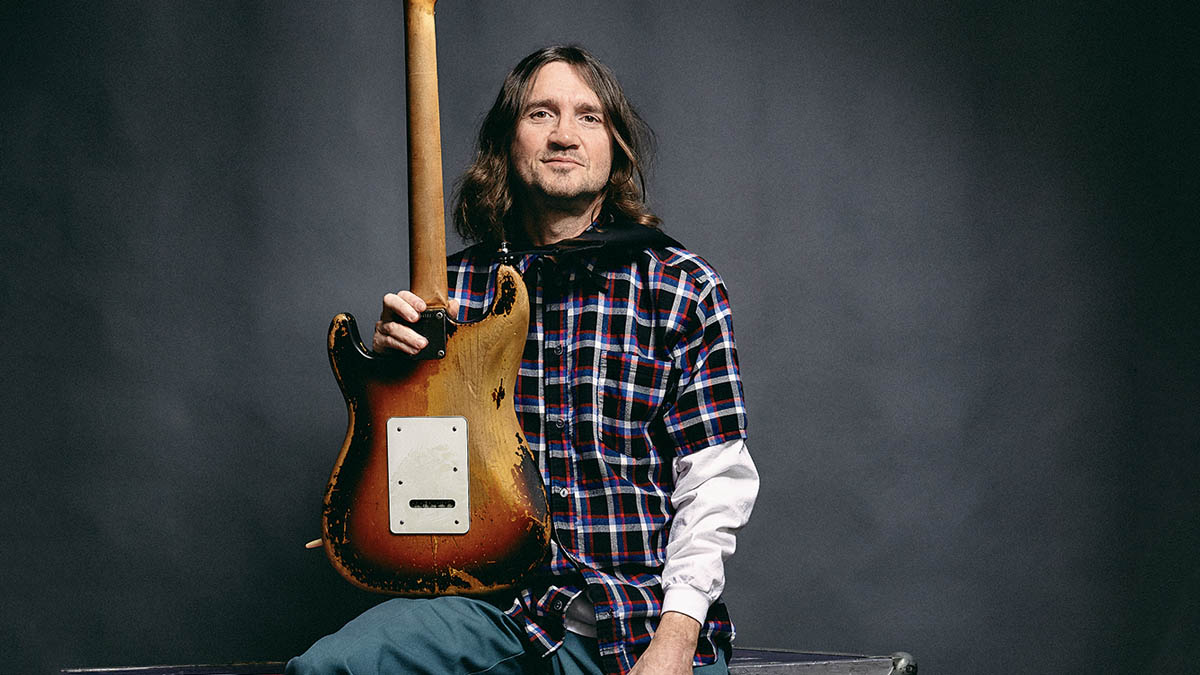

While John sought to explore new ground on Unlimited Love with his songwriting and technical philosophy, his gear ethos saw him reunite with the familiar tools he used to carve his name into the hearts of millions of young players.

“The main guitar that I played was my ’62 Strat, which is the same guitar that I got when I rejoined the band back in 1998,” he says of his go-to, which still features the original hand-wound pickups, but now comes loaded with an ILITCH hum-cancelling system. “Back in ’98 I didn’t have money for a Strat, but I told them all I had was a Fender Jaguar, and I felt that I should have a Strat for it to sound like the band.

“Anthony and I went to Guitar Center and he lent me the money to get a Strat, and it was the one that spoke to me off the wall. And ever since then, I’ve had many other Strats – from that period of time, generally – and that one that happened to be there that day, I’ve never found one better than that.”

Other old favourites also made an appearance: his maple-necked ’55 Strat – whose Seymour Duncans were recently replaced with a louder, better-matched set of pickups courtesy of Fender Senior Master Builder Paul Waller – as well as his ’61 Fiesta Red Strat and a Jaguar or two.

Acoustics – as heard on electro-folk groover Bastards of Light and delicate album closer Tangelo – were all Martin: two 1940s 0-15 mahogany models, a D-28 Dreadnought and a 12-string.

But there were some new-to-the-Chili Peppers additions, too, via a cabal of Yamaha SGs from the late-’70s and early-’80s. These dual-humbucker heavyweights became John’s main squeeze during his time away from the band, but proved to be the perfect guitars for overdubs during the album’s heavier moments.

I really loved both the guitar playing and the engineering of Greg Sage from the Wipers. He’s gotten some of the best guitar tones I think anybody’s ever recorded

He explains: “When there’s a heavy section with distorted powerchords and that kind of thing, a lot of the time the Strat was what I played in the basic track, but [doubled with a] Yamaha SG straight into the Marshall with no distortion pedal or anything, just getting the distortion from the amp. Quite a bit of the time it’s the Yamaha on the left, for example, and the Fender Strat through a distortion pedal on the other speaker. And there are even some mellow, soft things where it’s the SG.”

Amp-wise, the Marshall Silver Jubilee and Major stacks that flanked the guitarist at the Chili Peppers’ biggest shows were dusted off and taken out of retirement for the bulk of the tones, while a Roland Jazz Chorus wound up on a few dubs. But John’s lockdown reading also inspired him to seek out an old classic – which, as it transpired, had an unexpected connection to the band.

“I also had an Ampeg B-15,” he reveals. “I really loved both the guitar playing and the engineering of Greg Sage from the Wipers. He’s gotten some of the best guitar tones I think anybody’s ever recorded. He mentioned that he thought [the B-15] was the best amplifier ever made.

“So I bought one of those while we were recording the record to have a small amp to have a difference in tone for certain things. Then when I brought it in, Flea looked at it and he said, ‘That’s the same amp my stepdad used to have!’ His stepdad was a bass player and upright bass player, and that was the amp he would plug his upright bass into. That was a funny coincidence.”

But it was the Marshalls that would light the tonal fuse for some of the album’s guitar highlights, in particular the visceral, screaming feedback that tears across the solo sections of The Great Apes and The Heavy Wing.

Feedback is one of the funnest parts of making music for me

“Feedback is one of the funnest parts of making music for me,” John enthuses. “The approach to the feedback is just volume: having all four cabinets of two stacks on at once and finding the different places to stand where the really good feedback’s gonna happen, and walking around while I’m playing the solos to get different feedback on different notes.

“And just being extremely loud – like, so loud that if I didn’t have my headphones on, I couldn’t have stood there. The headphones were the only thing preventing my ears from getting blown out!”

The sheer volume meant that while many of the rhythm tracks were recorded live in the room, John was forced to track most of his solos as overdubs to avoid the amps bleeding too heavily into the drum mics.

But those band recordings found the guitarist fine-tuning his core sound, too, making one major adjustment to his Strat and amps compared with previous Chili Peppers outings.

“The bass [neck] pickup is on pretty much everything,” he reveals. “For a period of time, like By the Way or Californication, I was using the bridge pickup quite a bit. So, I noticed that when we were recording this, my treble was up on three on both of the Marshalls – in the old days, my treble was always on zero.”

As a result, the guitarist is still figuring out his pedalboard for the Chili Peppers’ upcoming live dates, and contemplating an EQ pedal to even out the treble response on those neck and bridge pickups. Naturally, the studio was ripe for effects experimentation elsewhere, too: modular and rack units received regular use, alongside more conventional pedals.

“I definitely used more delays on this than I had in any time in the past,” he says. “Mainly because I was inspired by that ’50s stuff – things like Gene Vincent or Elvis, where a lot of the time, there’s a slapback delay, not just on the guitar, but on the drums and on the vocal and bass and everything.

“So, I had a few: I had an MXR analog one, I had a [DeltaLab] Effectron II digital delay. Somebody suggested that I get one of these tape delays that they make now, the Fulltone Tube Tape Echo. That’s the last thing you hear on the album at the end of Tangelo, when all of a sudden there’s a delay that starts and then it builds into a kind of feedback for a second and then it’s noise.”

One new discovery was the Boss SD-1 Super Overdrive for a chunkier rather than more aggressive tone, as well as the MXR Super Badass Variac Fuzz for hairier solos and meatier overdubs. But at the time of writing, it remains to be seen how many of those will make it out onto the road, and whether John’s ’board will approach Slane Castle levels of enormity.

I like to have pedals that are just there for me to do something weird and different if the mood strikes me

“I never used very many!” he laughs at the mention of the cornucopia of stompboxes at his feet during the landmark 2003 show. “A lot of the time, one pedal was just for one particular song, and so I had to have it there just in case we played that song.

“And it was also because sometimes after being on tour for a long time, I get bored with the same sound from night to night. I like to have pedals that are just there for me to do something weird and different if the mood strikes me.”

I Like Dirt

John presents a guided tour of the key elements on his trimmed-down rehearsal pedalboard, stacked with pedals that wound up on Unlimited Love

Ibanez WH10 and Boss CE-1 Chorus Ensemble

“I used a lot of the same things – the same Ibanez wah-wah pedal, the old one. And the same old Boss chorus pedal, the Chorus Ensemble.”

Boss DS-2 Turbo Distortion and SD-1 Super Overdrive

“Normally, I would use the DS-2. But I also used the SD-1 – it’s less distorted. It’s not a super-extreme kind of distortion, but it can give you a powerful tone.”

MXR Super Badass Variac Fuzz and Custom Badass ’78 Distortion

“There was definitely a lot of MXR stuff on the album. They gave me a bunch of pedals early on. I used their fuzz tone quite a bit, not just for solos, but sometimes even for guitar parts for choruses or whatever. And a distortion pedal of theirs, too.”

MXR Reverbs

“That was on almost all the time [at rehearsals – the album features real room reverb]. It’s one of those things that comes from me being an engineer – I don’t think I used to be very conscious of room sounds, but now they’re very important to me to give some sort of sense of space to what you’re recording. And so it’s very subtle. It’s a very short room sound, but I just like to hear the guitar that way. The other is set for a more long kind of reverb.”

MXR Dyna Comp

“Sometimes the Dyna Comp was just exactly what I needed in terms of getting the right amount of sustain on clean things, and having a more Taffy-like kind of sound. I’ve loved the Dyna Comp ever since I was a little kid. I was a big fan of Adrian Belew when I was a youngster, and he had one of those on, like, all the time back in those days in the early ’80s.”

Around the world

Of course, there will be plenty of opportunity for Frusciante to push his tones and his playing on the Chili Peppers’ upcoming world tour.

Unsurprisingly, the setlist is likely to be heavily populated by greatest hits from his tenures with the band, as well as plenty of new material – at the time of Total Guitar’s interview, the band have been almost exclusively rehearsing all 48 of the songs they wrote for this album and its potential follow-up.

So, while the prospect of hearing Unlimited Love and even yet-to-be-released material is a tantalising one for fans, John emphasises how much he’s enjoying revisiting the old classics and adding some fresh, improvisatory twists.

“It really does feel good to play the old songs again,” he says. “There’s been a magic feeling for all of us going back to that material. And, you know, I like improvising on stage. So I look forward to the jamming parts of it, and making up new solos every night.

I haven’t really played in front of an audience in about 12 years. So it’s as new to me as writing rock music was when I rejoined

“[There’s] that reciprocal thing that happens with an audience, where their energy and the pressure of playing in front of them and not being able to rewind the tape and go backwards, it brings something out of you as a musician that there’s no way to recreate as a guitar player sitting in a studio recording your music by yourself, as I have in the past.

“I look forward to playing under that pressure, and letting go, and letting whatever spirits are with us that night come through me, and trying to match that feeling that gets generated between the band and an audience.” He pauses. “You know, I haven’t really played in front of an audience in about 12 years. So it’s as new to me as writing rock music was when I rejoined.”

Yet Frusciante has more than settled into his old role; it’s as if he never left. And while he’s brought some new tricks from an engineering perspective – citing his explorations of backwards delay and reverb and modular guitar treatments as highlights – it’s rediscovering that raw musical connection, and the simple joys of playing with like-minded musicians, that’s kept things exciting and fresh.

All in all, it paints a rosy picture of John’s third act with the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

“There’s an appreciation of the chemistry that I can’t say I really had towards the end of being in the band last time,” he admits. “An appreciation of what we’re capable of – when you get so used to something, you sometimes tend to take things for granted.

“I’d had lots of time making music where I do whatever I want. And that was great. And I continue to do that. But it seemed like a really good step for me as a human being to try to play in a band again. Most of all, I just have a lot of fun playing with those guys.”

- Thanks to John’s guitar tech, Henry Trejo, for his assistance with this feature.

Mike is Editor-in-Chief of GuitarWorld.com, in addition to being an offset fiend and recovering pedal addict. He has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University, and over a decade's experience writing and editing for guitar publications including MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitarist, as well as 20 years of recording and live experience in original and function bands. During his career, he has interviewed the likes of John Frusciante, Chris Cornell, Tom Morello, Matt Bellamy, Kirk Hammett, Jerry Cantrell, Joe Satriani, Tom DeLonge, Ed O'Brien, Polyphia, Tosin Abasi, Yvette Young and many more. In his free time, you'll find him making progressive instrumental rock under the nom de plume Maebe.

“I loved working with David Gilmour… but that was an uneasy collaboration”: Pete Townshend admits he’s not a natural collaborator – even with bandmates and fellow guitar heroes

“This guy kept calling saying, ‘I’ve never been in a band before, but I’m the best guitarist ever.’ When I heard him play it was like a fire from heaven”: The life and times of Killing Joke visionary Geordie Walker – the guitar hero’s guitar hero

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Can't Stop [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/8DyziWtkfBw/maxresdefault.jpg)

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)