“I wanted a whole bunch of pickups, four or five. But Leo said they wouldn’t fit”: The creation and evolution of the Stratocaster, Leo Fender's greatest invention

Timeless, iconic, yet also indisputably a product of the era in which it was designed, the Stratocaster was shaped in huge part by a few oft-overlooked players – one of whom suggested the whammy bar so he could get more money as a session guitarist

The following story was originally published in the July 2004 issue of Guitar World.

On its 50th birthday, which arrives this year, the Fender Stratocaster is looking even more youthful, cool, and ultramodernist suave than David Bowie did on his 50th.

The Strat remains the ultimate playing machine – ergonomic, responsive, sexy.

A young guitarist who picks one up for the first time today experiences much the same thrill players felt in 1954. The thing fits like a glove.

Before your mind even thinks to look for the volume knob and the tremolo bar, your fingers are already caressing them, and before you quite know what’s happening, your hands are producing “that Strat tone.”

It is one of the most distinctive sounds in all of guitardom – crystalline and translucent as clear running water, whether the guitar is plugged straight into an amp or channeled through a shimmering labyrinth of chorus, echo, and reverb. And even under the heaviest, filthiest distortion, that clarity is somehow still there.

“In my opinion, no instrument cuts across as many musical genres as the Stratocaster,” says Richard McDonald, Fender’s Vice President of Marketing. “An amazing body of music has been made on the Stratocaster. And if you’re inspired by that music, if you want to replicate it or if it’s just part of your musical background and learning, the sound of the Stratocaster guitar is embedded in your being.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The list of legendary guitarists closely associated with the Strat is awe-inspiring; it includes Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, David Gilmour, Frank Zappa, Mark Knopfler, Yngwie Malmsteen, Bonnie Raitt, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, to name just the cream of the crop.

What started as a guitar model in 1954 has become an industry in its own right. Fender currently produces some 20 signature-model Stratocasters, and the complete Fender/Squier line embraces more than 100 Strat variations.

Fender Senior Vice President of Market Development – and noted industry wag – Ritchie Fliegler declines to say how many Strats Fender were sold last year, but he offers, “It’s somewhere between a shitload and a fuckload. I can tell you that.”

The genesis of the Strat coincided almost miraculously with the birth of rock and roll. Three months after Fender’s April 1954 announcement of the Stratocaster, Elvis Presley released his first single, That’s All Right, on Sun Records.

Some six months after the first Strats rolled off Fender’s assembly line, in October ’54, the film Blackboard Jungle jolted America and the world with the rebellious new sound of mid–20th century youth gone wild.

All of which meant little or nothing to Clarence Leo Fender, a hardworking guy then in middle age who always said he preferred country music.

Even if he hadn’t invented the Stratocaster, Leo’s place in guitar history was already assured by 1953, when work on the Strat is generally thought to have begun. By this point, Leo had already given the world the Broadcaster (1950), which of course evolved into the Telecaster (1951), the first mass-produced solidbody electric Spanish-style guitar.

It was the instrument that introduced such landmark innovations as the bolt-on (as opposed to glued-in) neck, the one-piece maple neck, six-on-a-side tuning pegs, and distinctively bright-sounding single-coil pickups. Many of these design epiphanies would be carried over into the Stratocaster.

Place a Telecaster next to a Stratocaster, however, and it immediately becomes clear that Leo made a quantum leap between ’51 and ’54.

So what happened? Let’s start with what is arguably the Stratocaster’s most distinctive feature – its contoured body. The general outline is an outgrowth from another major Leo Fender innovation, the world’s first electric bass guitar, the Precision Bass, which had been introduced in 1952.

The PBass was the first Fender instrument to sport a double-cutaway body with extended “horns.” The horns were provided to help balance the instrument, which had a larger headstock than any previous Fender guitar. The Strat body represents an elegant refinement of this concept.

But that’s just the silhouette.

For a true and complete appreciation of the Strat body's beauty, it is necessary to examine it in three dimensions.

The Telecaster peg head was very small. People used to make fun of it – ‘Looks like a bare foot,’ and so on

George Fullerton

While the Tele is a flat slab of wood, the upper bout of the Strat body is rounded and gracefully contoured, scooping dramatically inward at the back, where the guitar meets the player’s torso, and curving more gently at the front, where the guitarist’s forearm rests. It looks like some surfboard designed to ride the rings of Saturn. But it’s all eminently practical.

The Strat’s body contours are the result of input Leo Fender received from professional guitarists working in and around Fullerton, California, the Los Angeles backwater that has long been Fenderland.

A guitarist named Rex Gallion is thought to be the first musician to tell Leo that the back of the Tele’s body dug painfully into the player’s rib cage. This observation was loudly seconded by country-and-western picker Bill Carson, who was to become a key member of the Strat design team.

“We respected [Carson’s] playing and leaned on him for advice,” Leo Fender told one journalist. “He was kind of our favorite guinea pig for the Strat, because we needed somebody who was dedicated to getting the job done.”

Helping Leo interpret the wishes and dreams of his guitarist consultants were Fender staff members George Fullerton, Forrest White, and Freddie Tavares. It was Tavares who first took pencil to paper and made the first sketches of what would become the Stratocaster body.

Guitar historians have a tendency to chase their own tails adjudicating who did what in designing the Strat. But what often goes overlooked is the credit due to the zeitgeist.

While it still looks astonishingly contemporary today, the Stratocaster is a quintessential piece of Fifties Moderne design. Its lines echo the contours of Charles Eames’ epoch-defining molded plywood chairs, of Heywood-Wakefield living room suites, or the coffee shops in the Southern California “Googie” style of architecture.

In his office at Fender’s current Scottsdale, Arizona, headquarters, Ritchie Fliegler fishes in his top desk drawer and pulls out an old Fifties drawing template.

“There isn’t a line on the Stratocaster that can’t be found on this,” he announces.

In our current era, when even squirt guns are designed using thousands of dollars’ worth of CAD/CAM software, this is a point well worth remembering.

The Stratocaster is the product of a more simple and idealistic era – a time when people felt they could change the world with paper, pencil, and maybe a few hand tools. While the Telecaster came out a few years after World War II, it still smacks of wartime attrition in many ways, which is why it’s such a cool, boxy, “commando” type of guitar.

The Strat, however, is an icon of post-WWII prosperity and optimism. It shares the confident flare of a full-length Fifties pleated skirt, the unstoppable thrust of a Cadillac tail fin. This can readily be seen when one compares the Tele and Strat headstocks. The former is small and cramped, like a tenement flat; the latter is spacious and opulently contoured, like a luxe house in the suburbs.

“That Telecaster peg head was very small,” George Fullerton once acknowledged, “and people used to make fun of it – ‘Looks like a bare foot,’ and so on – but there was a reason for doing that.

“Supplies were scarce in those days. We used to buy maple wood, and a lot of pieces were fairly narrow, so we designed a way we could get two [necks] out of it by having one end one way and the other end the other way. That wouldn’t work with the wider Strat peg head, so we had to spend more money on it.”

The Strat headstock seems to have been influenced by the machine head on an earlier guitar, designed by Southern California luthier Paul Bigsby for the legendary picker Merle Travis. Another Bigsby contraption – his vibrato arm tailpiece, which was starting to appear on guitars made by Gibson and Gretsch – may have provided the impetus for the Strat’s own whammy system.

I wanted a whole bunch of pickups, four or five. But Leo said they wouldn’t fit

Bill Carson

This feature was roundly championed by another key player in the Strat story, Fender marketing manager Don Randall. With a keen eye to what the competition was doing, it was Randall who pressured Leo Fender to come up with a guitar that could join the Telecaster in forming a complete line of Fender electric guitars – a range of products that could be offered for sale in music stores.

In 1952 Gibson had introduced the Les Paul solidbody electric guitar, the company’s upmarket response to the Telecaster’s popularity. Randall felt a clear need for Fender to have its own “classy” instrument. Hence, when the Stratocaster was released, it sported a two-tone Sunburst finish redolent of fine woodworking, and up-to-the-minute features like a whammy bar.

Like many great cultural moments, the Stratocaster arose from the union of art and commerce. Another staunch endorsee of the idea that the Strat should have a vibrato arm was Bill Carson, who felt he could earn double scale on session dates if he had a device that would enable him to imitate the glissando of a pedal steel guitar.

Carson was the driving force behind much of the Strat’s distinctive hardware. He was the one who insisted that the instrument have six individual, adjustable string saddles – a first in guitar design.

Leo had gone halfway there by endowing the Telecaster with three saddles, with two adjacent strings sharing each saddle. But with this system, as Carson pointed out, it was impossible to intonate the instrument perfectly.

Carson also had a lot to do with the Stratocaster’s pickup configuration.

“I wanted a whole bunch of pickups,” he told one interviewer: “four or five. But Leo said they wouldn’t fit.”

And so the Strat was invested with its now-classic three-pickup array.

The bridge pickup was placed at an angle so as to coax more treble out of the high strings, but it also lends tremendous aesthetic appeal to the instrument, forming a graceful angle that leads the eye to the Strat’s constellation of three control knobs. The latter are placed within easy reach of the player’s picking hand – a virtual invitation to incorporate volume swells into one’s technique.

The decision to give the Strat no more than three pickups may have also been determined in part by the limited range of selector switches available on the mid-Fifties parts market.

“The switch on the Strat had three positions,” Leo Fender has noted, “and that helped decide the third pickup – and I think that Carson was agreeable that this would be a good idea.”

But players quickly discovered that extra sounds could be wrested from the Strat by jamming the switch between positions. This could be accomplished by inserting a matchbook cover or some other object into the switch. Thus, two pickups could be on at once, and select frequencies from each pickup would cancel one another out.

While the term is, strictly speaking, not technically correct, these sabotaged switch positions have come to be known as the Strat’s “out of phase” sounds. Over time, they’ve become an indispensable part of the instruments’ timbral palette.

When the Stratocaster – Don Randall came up with the name – first hit the market in late 1954, it was only available with a two-tone Sunburst finish and one-piece maple neck.

Several minor details of these first Stratocasters differ from the Strats we know and love today.

A different kind of plastic was used for the pick guard, for instance, and the lower part of the tone knobs, called the skirt, was smaller and less flared, hence the term “mini-skirt” knobs. But it was essentially a Strat, possessing the same distinctive tonal qualities and visual appeal of today’s Stratocasters.

Where the Telecaster was very much a country-and-western guitar, the Strat was a rock and roll machine right from the start.

In the hands of early rock and roll pioneers like Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps, the futuristic Strat seemed custom-made for this exciting new form of music. Meanwhile, early sides by Buddy Guy and Otis Rush showed the Strat’s stinging blues potential to great advantage.

By 1959, the Stratocaster had undergone a few significant changes.

Fender temporarily retired the one-piece maple neck for the Strat and introduced a two-piece design with a rosewood fingerboard mounted on a maple neck. The rosewood fingerboards produced a slightly warmer tone and found favor with many players.

The one-piece maple neck would be reinstated in ’67, giving Strat enthusiasts a choice of flavors. By ’59, the original two-tone Sunburst finish had evolved into a three-tone Sunburst with more of a reddish luster. More dramatically, Fender had introduced bold new custom color options like Fiesta Red. These DuPont Duco automotive paint colors further enhanced the Strat’s “hot rod” image.

As the Sixties dawned, the Strat became the official guitar sound of a new style called surf music, as pioneered by Dick Dale, the Ventures, and the Beach Boys. With the arrival of the British Invasion in late 1964, however, the Strat underwent a temporary eclipse in popularity.

The Beatles, Rolling Stones, and other top groups were more often seen with Rickenbackers, Gretsches, Voxes, and Gibsons in those days. Coincidentally, Leo Fender suffered a health problem around this time, and in 1965 sold the company to corporate giant CBS for a then staggering 13 million dollars.

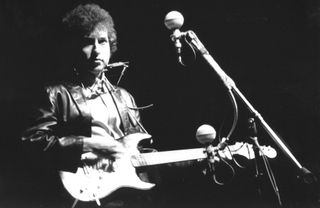

It was the end of the Strat’s first era, but the dawn of an extremely colorful second act. 1965 was also the year Bob Dylan shocked the folk community by “going electric” at the Newport Folk Festival, signaling the birth of folk-rock and the start of what many regard as rock music’s most fertile and expansive period.

The instrument Dylan chose to play on that momentous occasion was a Stratocaster. And by ’66 or so, the Who’s Pete Townshend – initially a Rickenbacker man – was using the more durable Stratocaster for the group’s violently explosive live shows, wresting a wild array of feedback and overdriven tones from his Marshall stacks, then a brand-new innovation.

All this wasn’t lost on the man who was to become perhaps the single greatest Stratocaster icon of all time.

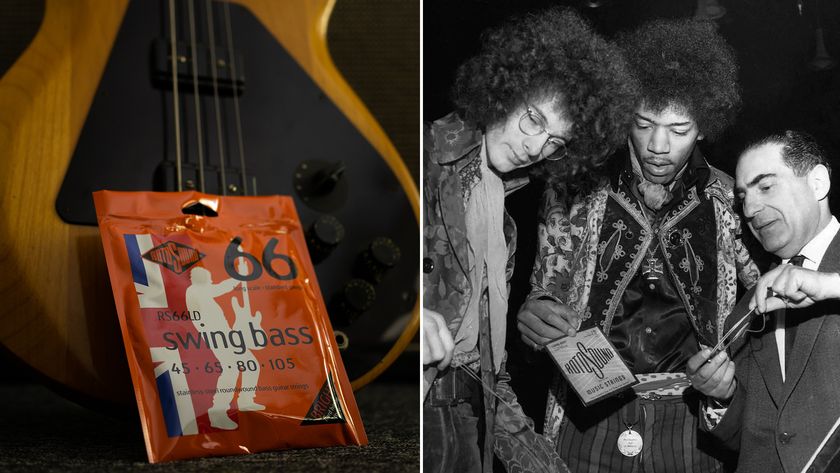

The first album by the Jimi Hendrix Experience was issued in 1967, the same year that the group made its stunning American debut at the Monterey Pop Festival in the hippie haven of Northern California.

A lefty who played right-handed guitars turned upside down and restrung for left-handed playing, Hendrix virtually reinvented the Stratocaster, pushing the instrument to its limits, creating sounds Bill Carson never dreamed of. Hendrix was a pivotal figure in the invention and popularization of psychedelic music, but his music has transcended the era that first brought him to fame.

As the sun rose on the Seventies, heavy metal blossomed as one offshoot of the amped-up Strat style that Hendrix helped forge. One of the music’s first and most enduring guitar heroes was the Strat-wielding Ritchie Blackmore.

By the early Seventies, Eric Clapton had also become a conspicuous Strat player, having previously used Gibsons for much of his Sixties tenures with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Cream.

Clapton’s switch to Strats coincided with his leadership of Derek & the Dominos, whose 1970 album Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs was one of Slowhand’s greatest commercial successes. His ax of choice during this period was “Blackie,” a hybrid instrument assembled from the parts of several vintage Stratocasters.

In 1976, Jeff Beck also went over to Strats, just in time for the making of Wired – one of the best-selling instrumental albums of all time and one of the most precious gems in the entire Beck canon.

It is significant that not one but two of rock guitar’s foremost heroes forged their mature styles on Stratocasters. The Strat seemed to bring out the introspective side of Clapton’s blues classicism. And Beck’s use of the Strat whammy bar is every bit as revolutionary as Hendrix’s. Both Clapton and Beck have been closely associated with the Stratocaster ever since the Seventies.

In 1977, the five-position pickup switch finally became a standard Strat feature. Coincidentally enough, the following year saw the debut of a man whose name would become synonymous with the Strat’s “out of phase” pickup tone.

Leading Dire Straits, Mark Knopfler forged a lyrical, legato style that was far removed from the overdriven frenzy of Beck or Hendrix, but no less expressive.

But while the Seventies witnessed some of the greatest Strat playing of all time, the actual instruments produced during this era are not particularly popular with guitarists or collectors. Among other things, this was the era of the infamous tilt neck, held in place with three bolts, instead of the traditional four. But even these Strats have their aficionados, including Billy Corgan during his Smashing Pumpkins years.

The early Eighties saw a revival of interest in the blues, spearheaded by two towering giants of the Stratocaster, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Robert Cray. The decade will also be forever associated with shred mania, a genre whose patron saint, Yngwie Malmsteen, has always been a devotee of vintage Strats equipped with scalloped fingerboards.

At mid-decade – in March 1985, to be precise – Fender was purchased by a consortium of investors headed by Bill Schultz, a musical instrument industry vet who’d been acting as a consultant to Fender since ’81.

One of Schultz’s prime directives was to restore the Stratocaster to the pristine glory of its earlier years.

To this end, Fender instituted the American Standard Series, which combined classic Strat styling with features, such as the five-position pickup selector, that had become de facto standards through the years. Meanwhile the Fender Custom Shop, also established in ’86, launched a series of meticulously crafted vintage reissues, starting with ’57 and ’62 “Mary Kaye” models (blonde finish with gold hardware, named for guitarist Mary Kaye, an early Fender endorsee).

At the same time, Fender’s new owners sought to bring the Strat and other classic models into the future, forging relationships with innovative designers like pickup guru Don Lace and hardware mavens Trev Wilkinson and Floyd Rose.

The advent of the Stratocaster equipped with a Floyd Rose Tremolo system is what brought Frank Zappa into the fold. This was what Frank used on much of his highly virtuosic latter day work, up until his death in ’93.

The Strat cut a figure on the Nineties grunge scene thanks to the aforementioned Billy Corgan and Pearl Jam's Mike McCready. More recently the Stratocaster has become the instrument of choice for the pop-punk boom.

“Probably the biggest trend in Stratocaster bands over the last few years is guys like Tom DeLonge of Blink-182,” says Fender's Richard McDonald. “Look at all the bands where guys are downstroking on a Strat. And that goes back to Billie Joe Armstrong of Green Day.

“Also recently we've had bands like the Vines and the Strokes using Stratocasters. I'm not sure what category you'd throw them in – just good old rock and roll, I guess.”

Meanwhile, the Strat continues to evolve. Recent design refinements include a contoured neck heel – probably the only surface on the thing that hadn't previously been contoured – and the S-1 pickup system. The latter is particularly cool.

By means of a two-way switch built into the volume pot, any of the five selectable pickup configurations can be wired in either series or parallel. It's an innovation that opens up many new tonal subtleties.

Fender is planning to celebrate the Strat's 50th birthday in grand style. The Fender Custom Shop will issue a limited-edition 1954 replica Strat, meticulously detailed down to specially retooled knobs and tremolo arm tips to match the quirks of the very first Strats.

The company will also issue a limited-edition 50th Anniversary American Deluxe Series Stratocaster and 50th Anniversary American Series Stratocaster, instruments that combine the look of the original '54 model with modern features such as the aforementioned S-1 switching. Beyond this, there will be everything from star-studded concerts to Strat-emblazoned commemorative Miller beer cans.

A fitting tribute, considering that the Stratocaster is the ultimate baby boomer. Born in the Fifties, it refuses to grow up. Having participated in many of rock history's greatest moments, it's still running with the young punks.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“Satin Stratocaster dreams”: Fender and Thomann have produced two new exclusive Stratocaster lines – and their prices rival existing US and Mexico-made models

“A new take on the classic”: Gibson gives its Les Paul Special an ultra-rare pickup overhaul with new Mini Humbucker models

![Green Day - Basket Case [Official Music Video] (4K Upgrade) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/NUTGr5t3MoY/maxresdefault.jpg)