“Ibanez and Japanese brands in general were irritating the hell out of Gibson, Fender and other US companies targeted by copyists”: From copies to innovations – the origin and rise of Japanese electric guitars (and the truth about ‘lawsuit’ guitars)

We dig into the Japanese guitar industry of the 1960s and ’70s and find notable brands, mischievous copies, diligent makers and original designs that led to the instrument’s renaissance in the 1980s and beyond

It’s the late ’70s, and Paul Stanley of KISS tells an interviewer about the band’s great successes – he guesses they’ve sold something like 20 million records, and they’re just back from a Japanese tour.

It was there, he says, that he found out more about the abilities of Japanese guitar makers.

He discovered they have the skills, as he puts it, “to make anything”. That’s a lot more than can be said for America at the moment, he adds. “Japan,” Stanley concludes, “really is the country of the future.”

Japan’s guitar industry was certainly healthy when he made those comments, and it surely had no reason to doubt that the future would be just as rosy. It had overcome a shaky start, when critics said it simply copied well-known designs, and it had weathered some crippling ups and downs.

Now, though, Japanese companies were showing themselves in many cases to be the equal of American makers – and in some cases perhaps to have overtaken them. Let’s take a look at how that came about and who made it happen.

Early Originals

The origins of perhaps the most famous Japanese guitar brand, Ibanez, lie with its parent company, Hoshino. Matsujirou Hoshino started the family business around 1900 in Nagoya, about 175 miles west of Tokyo, when he opened a store to sell books and stationery.

He soon added a section for musical instruments run by his son, Yoshitarou, who set up Hoshino Gakki Ten – the Hoshino Musical Instrument Store company.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Following a tour by the great Spanish classical guitarist Andrés Segovia in 1929, which inspired many Japanese people to take up the instrument, Hoshino began importing Salvador Ibáñez guitars from Spain.

The Spanish factory closed by the late ’30s, so Hoshino adopted the name for itself and made acoustic guitars in Japan, at first branded as Ibanez Salvador and soon simply as Ibanez.

The company began to offer electric guitars around 1957, and from then until the mid-’60s Hoshino made some instruments itself in its new Tama Seisaku Shone factory, set up in 1959, but also bought in guitars from other Japanese firms.

In Japan in the ’60s, many budding young guitarists were just as keen to form groups and find stardom as anyone in America, Britain – or anywhere else that the pop bug had bitten

Some of the early Japanese guitars from this time had features loosely borrowed from American Fender and Gibson, say, or British Burns models. Not exactly copies – they didn’t duplicate every detail of an existing model – but more like Japanese interpretations of Western designs with touches of Eastern taste.

In Japan in the ’60s, many budding young guitarists were just as keen to form groups and find stardom as anyone in America, Britain – or anywhere else that the pop bug had bitten. In Japan, the scene was known as Eleki and then Group Sounds, and bands such as The Spacemen, The Blue Comets, and The Jacks enjoyed success.

Japanese companies, including the big names like Teisco and Hoshino/Ibanez, not only sold electrics to that growing home market but also began to actively export instruments, notably to wholesalers in Europe, the United States, Australia and elsewhere. And a complication arises here for anyone trying to grasp the ins and outs of Japanese guitar history.

It ought to be simple: companies manufactured guitars and either sold them at home or exported them. However, many of the foreign customers who bought instruments from Japan had their own brand names put on the guitars.

This is often called OEM – original equipment manufacturer – which means a company that makes a product to be sold by another company under its own name. It meant nearly identical instruments being sold in various locations bearing different brands and, conversely, guitars with one brand originating from a variety of sources.

Add to this an array of often interrelated factories and sales agents and distributors, and the picture can be a baffling one.

For example, the American and British firms that bought from Hoshino in the early days used brands such as Antoria and Star in the UK and Maxitone and Montclair in the USA, among several others, although some guitars did have Ibanez on them. Some Ibanez catalogues from the period feature guitars with blank headstocks, accentuating the ‘your-name-here’ policy.

There was similar OEM activity at Teisco – a firm born in Tokyo in the ’40s, adding guitars in 1952 and electrics a couple of years later. Its exports to Europe and America had brand names such as Audition, Top Twenty, Gemtone, Jedson, Mellowtone, Kent, Kingston, and Norma.

Teisco also sold a line of models at home with its own Teisco brand and, from around 1965 in the USA, Teisco Del Rey.

Teisco had success through its American distributors – at first Westheimer, who later bought from Kawai, and then WMI, who came onboard around the time the Teisco Del Rey brand name appeared.

The Sears, Roebuck mail-order catalogue company was another US customer for Teisco, who provided some of the guitars Sears sold with its own Silvertone brand.

And here’s another wrinkle: as with many of the firms for whom Teisco made guitars, the Silvertone models exported to America by Teisco were sometimes almost identical to a Teisco-brand instrument sold at home. An example of this is the mid-60s four-pickup Silvertone 1437, which in the homeland was the Teisco ET-440.

In 1965, Teisco sponsored a movie, Eleki No Wakadaisho (‘The Young Electric Guitar Wizard’). It starred guitarist Yūzō Kayama as a member of the fictional Young Beats group, who entered a battle-of-the-bands competition – and, naturally, they all played Teisco guitars through Teisco amps.

Despite such cultural landmarks, as well as the opening of a new factory in Okegawa and the export of instruments to Britain, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the US and elsewhere, Teisco battled with financial problems. It declared bankruptcy early in ’67 and was bought by Kawai, which continued to use the Teisco brand for a few more years.

Guyatone, Kawai, Yamaha, Aria

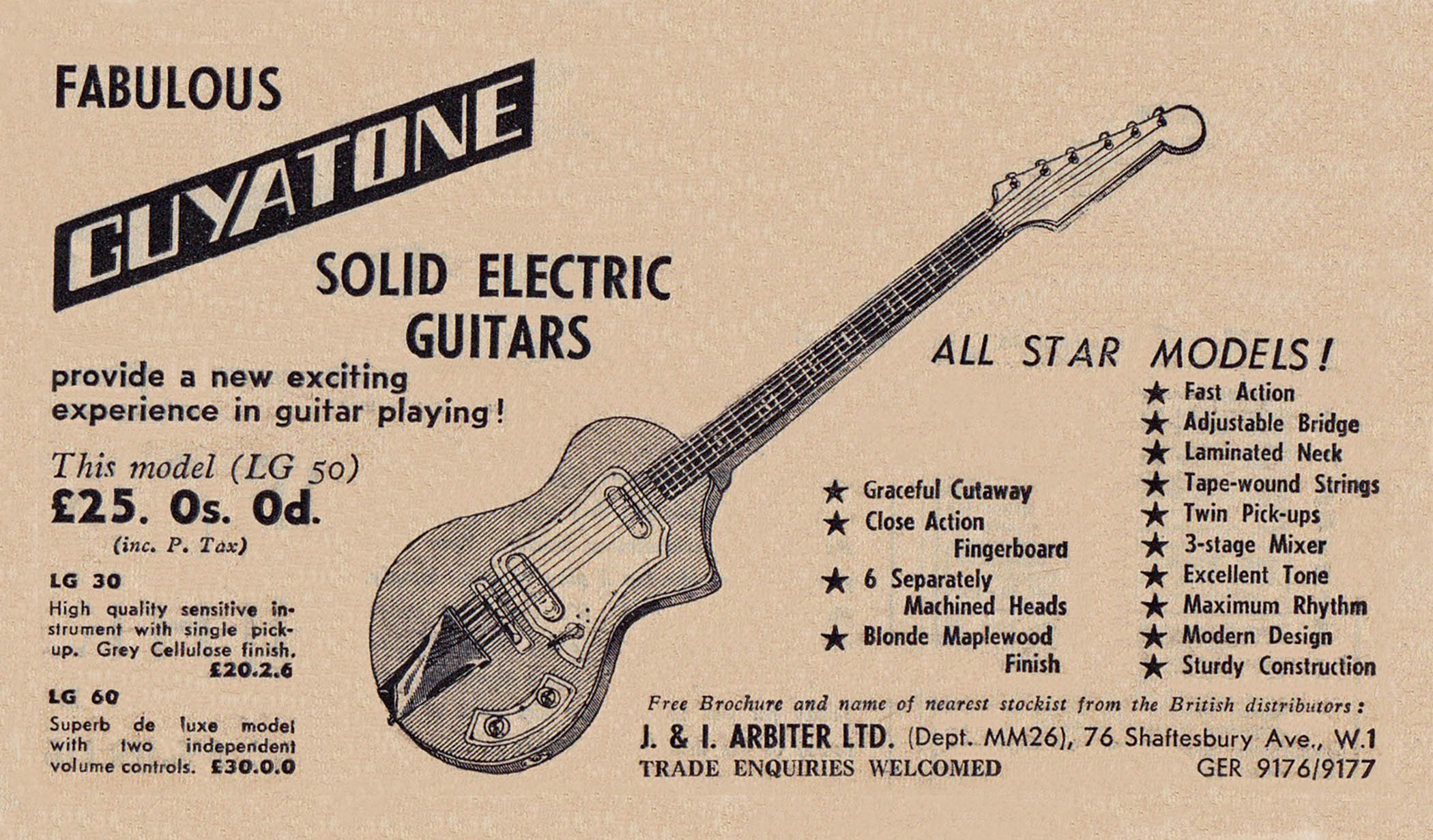

Rivalling Teisco and Hoshino/Ibanez as the big name in ’60s Japanese guitars was Guyatone. It was founded by Mitsuo Matsuki in Tokyo in the 1930s, introduced its first solidbody electric in the mid-’50s, and its LG models in particular proved popular in Britain and elsewhere toward the end of that decade.

These early LGs were sold in America by Buegeleisen & Jacobson (as Winston), and in Britain by Arbiter (as Guyatone) and JT Coppock (as Antoria).

Guyatone’s range and quality expanded during the ’60s, with models such as the LG-160T, complete with a handy body-hole, as well as a couple of SG and MG hollowbodies, and the LG-200T, which had four pickups and multiple push-button selectors.

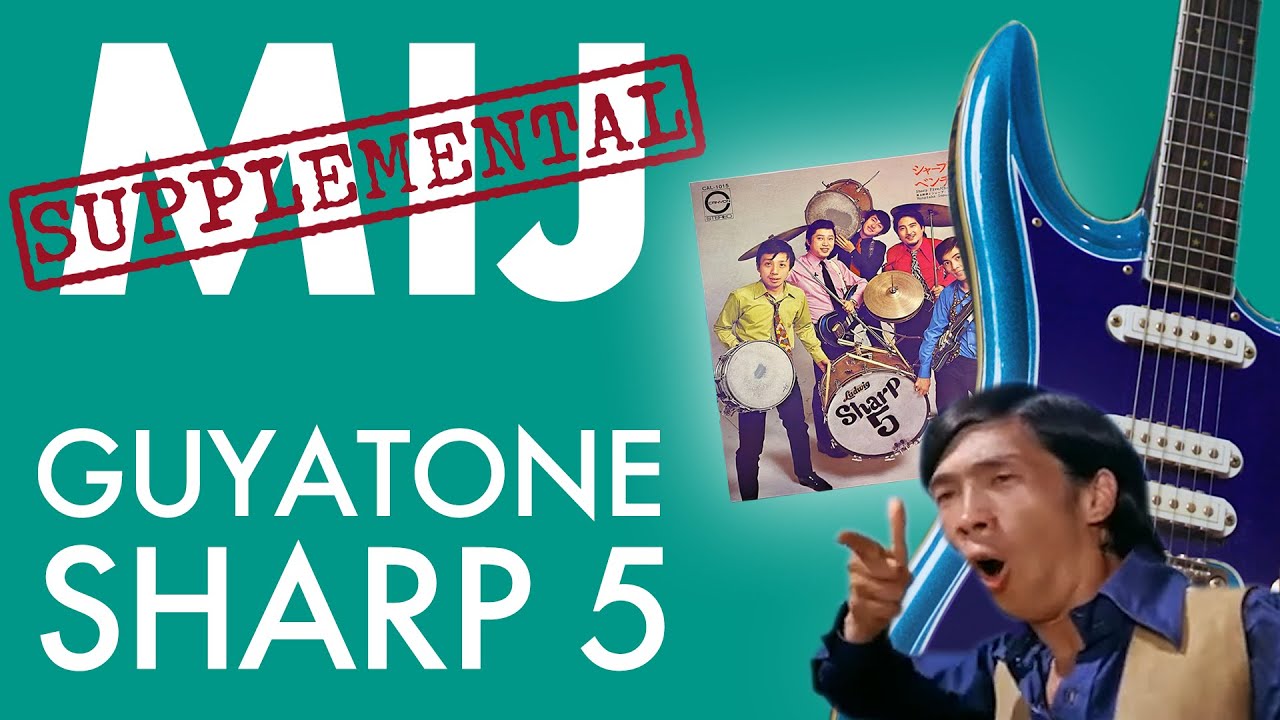

Probably the best-known Guyatone today is the Sharp 5 signature model, introduced in 1967. The Sharp 5 band, part of the Group Sounds trend that spread across Japan at this time, was led by Munetaka Inoue and guitarist Nobuhiro Mine, and their break came in ’67 when they signed to Columbia Records.

Guyatone saw an opportunity for a liaison with the band, renaming its LG-350T guitar as the Sharp 5 model. Mine played the 350 Deluxe, with blue finish, three pickups and gold-plated metalwork.

Kawai dates back to the 1920s, when Koichi Kawai started a keyboard company in Hamamatsu. The firm began making guitars in the 50s, expanding its Kawai-brand lines during the next decade and exporting widely to OEM customers.

Among the brand names used in the US were Domino, Kent, Kimberly and TeleStar. By the late ’60s Kawai had become another big player in Japanese guitar making.

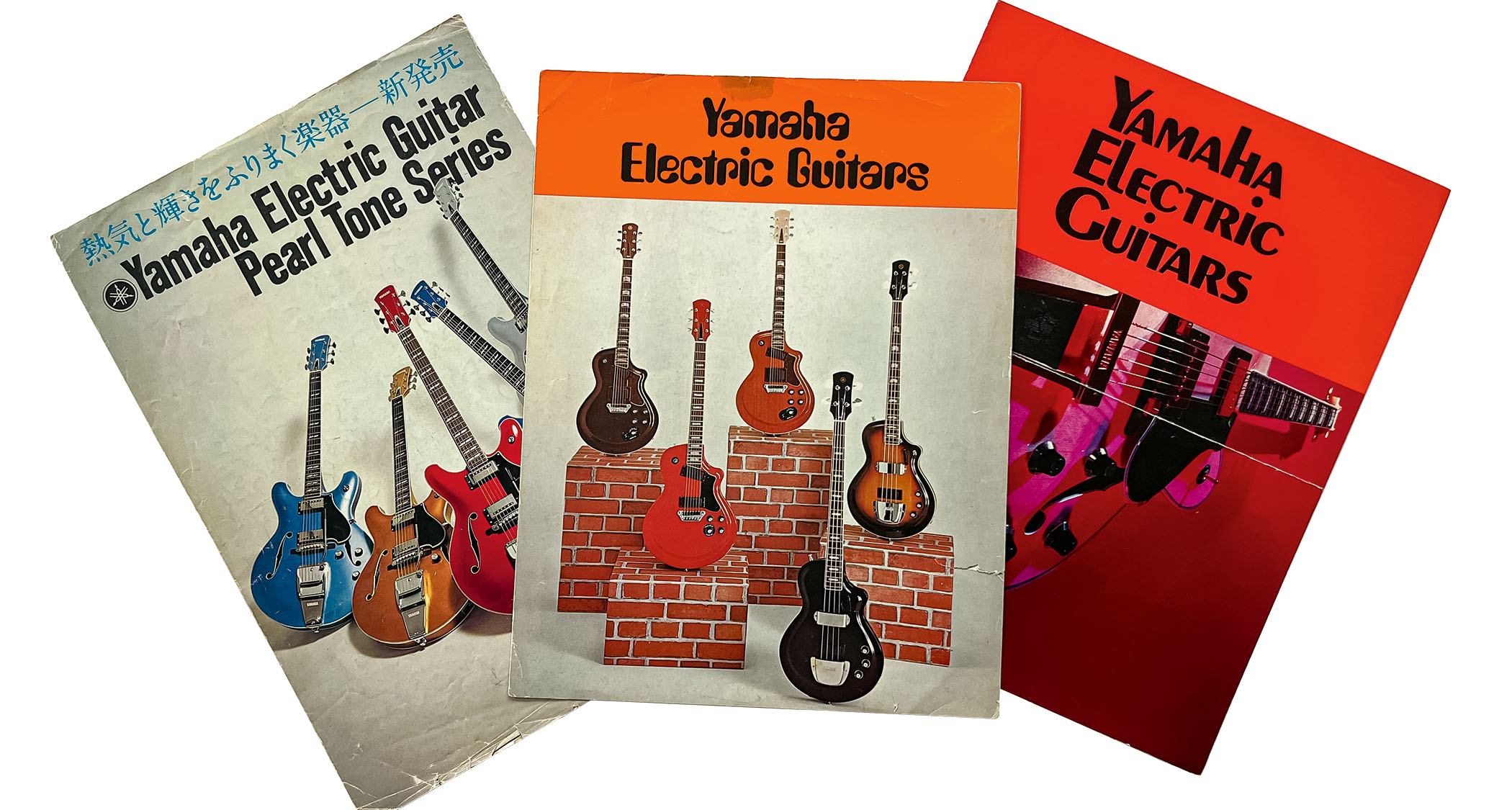

These companies still competed for attention in the home market, and a notable new contender in the mid-’60s was Yamaha. It was, of course, an old name, founded in the 1880s as a keyboard manufacturer and diversifying as the decades went by into many other areas, not least motorcycles.

The first Yamaha budget electrics appeared in 1964, and then the better SG models two years later. Among these early SGs were the conventionally shaped and Fender-inspired SG-2 and 3, along with the reverse-body Mosrite-influenced SG-5 and 7, with an extended lower horn to the body and a long, slim headstock.

The flipped-body style of Mosrite’s Ventures model was a popular shape among Japanese makers following the American band’s successful tour of the country in 1964.

The Arai company, founded in Nagoya by the classical guitarist Shiro Arai in 1956, made classicals at first but added electric guitars in the early 60s, soon using the Aria and Aria Diamond brands. In the ’70s and later the company would become better known for its Aria Pro II brand.

Aria was the Japanese distributor of Fender guitars in the late ’50s, so it’s not surprising that some of its own models were Fender-like in appearance.

The Japanese Guitar Game

Let’s step aside for a moment and play ‘Loser, Looker, Player’. We’ll tell you ours, to get things going, and then you can have a go.

LOSER: Our choice is an Ibanez copy of a Gibson double-neck. Did you say ‘so what’? Ibanez introduced the line in 1974, about six years after Gibson had dropped its SG-style originals, and offered a six-string plus 12-string (model 2402) and a six-string plus bass (2404).

So far, so Gibson. But here’s our choice of Loser: Ibanez Model 2406 boasted two six-string necks. Correct, two six-strings on one (rather heavy) body. Gibson had never made such a thing, of course, but Ibanez had other ideas. This guitar, it enthused, would be good to have to hand in “open-tuning slide guitar and standard tuning”. We rest our (rather large) case.

LOOKER: An impressive example of over-the-top Teisco Del Rey style was the solidbody Spectrum 5, introduced in 1966. It was a luscious creation, with a thin, curving, sculpted mahogany body, covered with what Teisco claimed as “seven coats of lacquer”, parachute-shape fingerboard inlays, a spring-less vibrato, two jacks for mono or stereo output, and three pickups, split so as to assist with the Spectrum 5’s stereo feed when required.

The model name derived from what Teisco described as “five different basic colour tones [that] can be produced with this unusual guitar”, indicating the colourful pickup and phase switches on the upper part of the model’s pickguard. Spectacular!

PLAYER: How about a Tokai Les Paul Reborn? The firm began soon after World War II in Hamamatsu and launched Tokai electrics in 1967. 10 years later, the copies began.

Yes, there were many copies about, but Tokai in particular and its Les Pauls-styles (and Strat-styles and more) made players think anew about what ‘Japanese guitar’ could mean – and sent shockwaves through parts of the instrument industry.

The Les Pauls came with a few different names during the key period from 1978 to ’85 or so, and they looked the part, too, some bearing ‘wow-could-it-be-a-’59’ flamey tops, and many found them to be great players at decent prices. One of Tokai’s cheeky British ads turned the tables with a headline that read: “Beware of imitations.” This did not go unnoticed.

Copycat Crazy

There was boom and bust in the Japanese guitar business in the period from 1966 to ’68. One of the factors may have been the USA’s doubling of customs duties on imported electrics, and domestically some makers were caught with excessive stocks when demand died, at home as well as abroad.

By 1976, Les Paul copies were the most numerous in the Ibanez catalogue, with more than 20 varieties on offer

Whatever the causes, the bust toppled Teisco, Guyatone and others, resulting in a reset of the industry. Some of the stronger businesses survived, including Aria, Fujigen and Yamaha.

But the upheaval at this time provides yet another complication for anyone expecting a straightforward situation where guitar A was made by B, has the brand C, and was sold by D. The rest of the alphabet will come in handy if you want to dig deeper.

To generalise, then, it was in the early ’70s that a wider move to copies began in Japan. These could still be described as interpretations of the real American things, but now there was no doubt about the models that provided the inspiration.

Hoshino had been sourcing guitars from Teisco and Fujigen Gakki since it shifted its Tama factory to drums only in 1965, and by 1970 Fujigen was its main supplier, coinciding with this emphasis on copies. Hoshino continued as a trading company, one that buys and sells products without manufacturing anything itself.

Fuji Gen Gakki Seizou Kabushikigaisha – the Fuji Stringed-Instrument Manufacturing Corporation – was started by Yuuichirou Yokouchi and Yutaka Mimura and produced its first guitar, a basic nylon-string acoustic, during 1960, adding electrics three years later.

It had a new factory operational by 1965, based in Matsumoto, home to several furniture makers and guitar builders. As well as its OEM work, Fujigen had its Greco brand, in partnership with distributor Kanda Shokai.

Fujigen’s Greco and Hoshino/Ibanez copies were among the most popular of the period, and some of the initiative to make and develop them came from American and British outlets.

The first British distributor to buy Ibanez-brand guitars from Hoshino was Maurice Summerfield, who started doing business with them in 1964. From the early ’70s, he added the CSL brand for electrics alongside Ibanez, and then the Sumbro brand as a cheaper line below Ibanez and CSL.

In America, one of the outlets Hoshino worked with was Harry Rosenbloom’s Medley Music store in Philadelphia, and his Elger Company became Hoshino’s eastern US distributor for Tama and Elger guitars, Elger banjos and Star drums.

In 1972, Hoshino and Elger set up a joint venture to become the American distributor of Ibanez guitars as well as Hoshino’s other brands and instruments, and a few years later Hoshino took sole ownership of the operation that had become its valuable American HQ.

Staff at the new offices, both Japanese and American, noticed that at first the quality wasn’t great on some of the guitars shipped over to them, and they fed regular suggestions and ideas back to Japan, many of which were used to broaden and improve the lines.

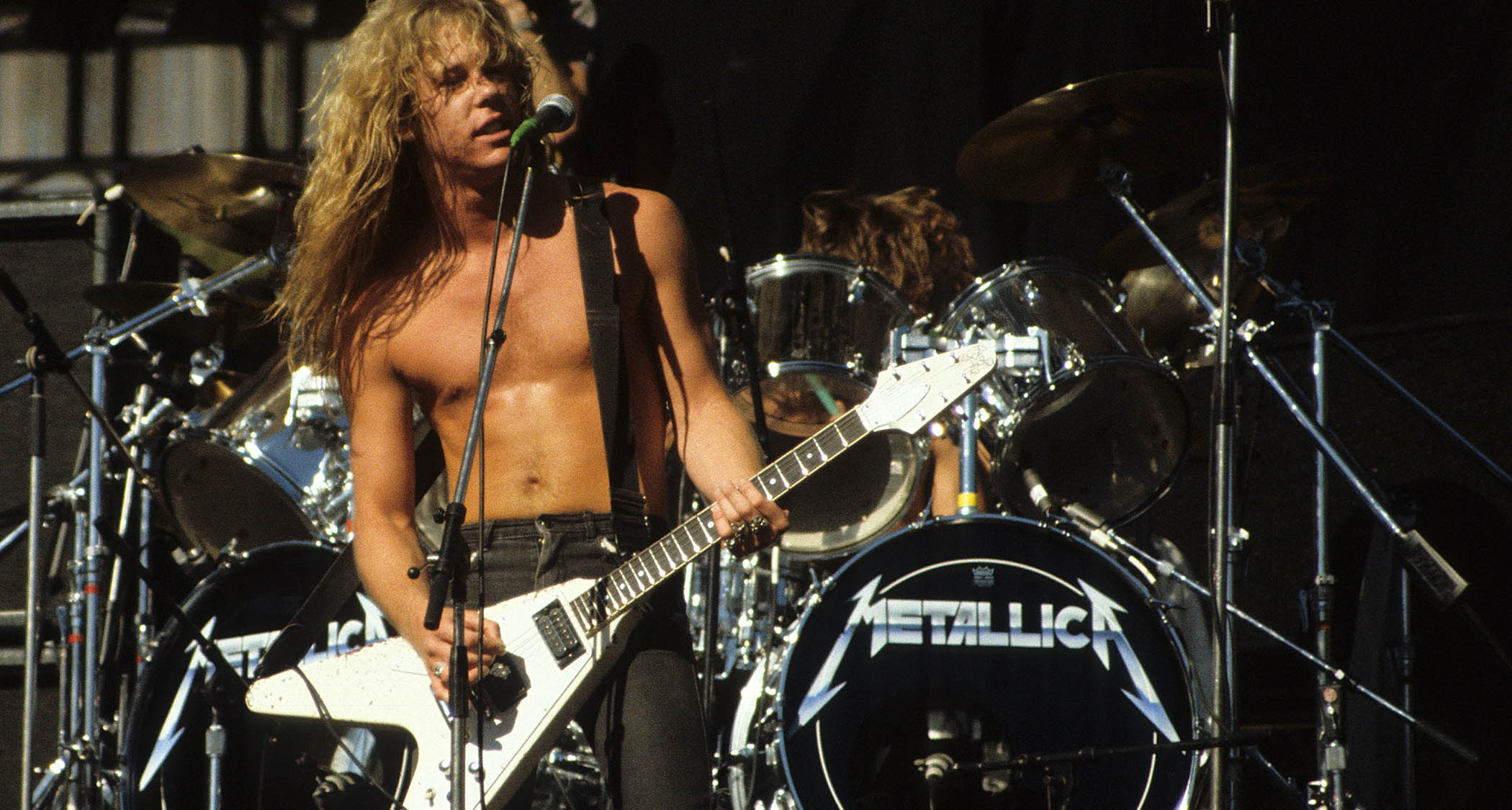

Maurice Summerfield in Britain recommended that Hoshino add to the line a copy of a Gibson Flying V, recently given a low-key revival by Gibson.

As with the original Les Pauls, players at the time were rediscovering the excellence of old Vs. Ibanez launched a Flying V copy in 1973 based on a late-’60s original that Summerfield sent to them, and soon a Gibson double-neck copy appeared, again thanks to Summerfield’s encouragement.

By 1976, Les Paul copies were the most numerous in the Ibanez catalogue, with more than 20 varieties on offer. In the USA, they were pitched from the cheapest, the best-selling bolt-neck $260 Les Custom 2350, through the $299.50 Les Deluxe 59’er 2340 in sunburst and the $340 Sunlight Special 2342IV, and up to the most expensive – a set-neck version of the 2350, the $495 2650CS Solid Body DX.

That same year, Gibson’s regular line of five Les Paul solidbody models ranged from the $599 Les Paul Deluxe to the $739 Les Paul Custom, so it’s not difficult to understand one of the prime attractions of the copies, beyond any considerations of accuracy or quality.

There were many other Japanese companies making copies, of varying quality and exported with any number of brands, including Penco, Mann, Jason, Kasuga, Heerby, Burny, Tokai, Fernandes, Honey, Conrad, Ventura, Fresher, Electra and HS Anderson.

Fujigen and Kanda Shokai’s house brand, Greco, was in the upper bracket of quality, and by 1981 Greco’s Stratocaster copy line ranged from the SE-380, which retailed at 38,000 yen, up to the SE-1200, at 120,000 yen.

A straightforward conversion into US dollars of the time provides an equivalent range of about $260 to $530. That same year, Fender’s cheapest Stratocaster retailed for $720.

Lawsuit? What Lawsuit?

You won’t get far in the world of Japanese electric guitar history without coming across the word ‘lawsuit’. In the ’70s, Ibanez in particular and Japanese brands in general were irritating the hell out of Gibson, Fender and the other US companies targeted by the copyists.

It wasn’t until 1977 that Gibson made a legal complaint to Ibanez (through its US arm, Elger). Gibson and Ibanez/Elger settled out of court, with Elger agreeing to stop infringing Gibson’s trademarked headstock design and to stop using Gibson-like model names in sales material. In February 1978, Gibson’s complaint was closed.

In fact, Ibanez was already using a new headstock design, and had been offering some original-design guitars for a number of years. That term ‘lawsuit’ stems from this brief legal spat and is often used these days to describe any Japanese copy guitar of the period, whether or not the brand suffered legal action.

Oddly, it’s gained a cachet, presumably because ‘lawsuit-era guitar’ sounds more dramatic than ‘70s Japanese guitar’.

One of the reasons Fender chose Fujigen to manufacture its first Squier guitars in the early ’80s was because Fender’s strategy to beat the Japanese copies was simply to make better copies itself, with the added prestige of its own brand. And Fujigen’s existing Greco guitars proved that Fujigen was already good at what Fender required.

Gibson later reset its Epiphone brand in similar ways – and Epiphones had first been made in Japan way back in 1969. These developments, and guitars such as Yamaha’s SG2000 in the ’70s and the Ibanez Steve Vai-related JEMs of the ’80s, would underline a new confidence among Japanese makers.

One of the original designs that Ibanez (and Greco) introduced well before the Gibson legal complaint was The Flash, introduced in 1975 and soon renamed the Iceman (Ibanez) and M series (Greco). There were influences at work, for sure, the body looking as if someone had given a Firebird a curved, pointed base and added a Ricky-like hooked lower horn.

But it added up to an attention-grabbing original. And in 1978, a signature version for Paul Stanley appeared. Ibanez also made him a custom PS10 with a cracked-mirror front, providing sparkling reflections at KISS’s already dazzling shows. No wonder Stanley thought that in the guitar-making world, Japan was the country of the future.

- This article first appeared in Guitarist magazine. Subscribe and save.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar

“Finely tuned instruments with effortless playability and one of the best vibratos there is”: PRS Standard 24 Satin and S2 Standard 24 Satin review