ZZ Top: A Texan in New York

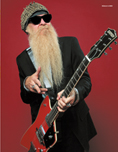

As ZZ Top prepared to release their 1999 album, the rockin’ and raunchy XXX, Guitar World spent a long and fascinating night on the town with Billy Gibbons.

2:47 A.M., ST. MARK’S PLACE, EAST VILLAGE, NEW YORK CITY

“Hey ZZ, rock on!” These words, shouted from a passing car, greet Billy F. Gibbons as he emerges from a corner newsstand and strides to a waiting limo. With Billy’s famous Two- Foot Doorman (one of the man’s many odd names for his beard), it would be hard for a passerby not to recognize ZZ Top’s eccentric, urbane guitarist, particularly on a street that’s all but deserted here in the small hours of the morning. But for Billy, this unsolicited exhortation to “rock on” has an almost occult significance. It underscores a point he’s been making all evening. Back in the limo, he leans in close and speaks low:

“I’m hearing a lot of scuttlebutt saying that rock music is back. People just wanna rock again. And it’s really gonna be wild this go-around, because all the elements left over from whatever was hot on the charts last week are going to be mixed in. Of course, rap and rock have been shown to be able to live together. So we might get this real wacky collision that’s just totally crazed. The wilder the better, I think.”

ZZ Top’s XXX certainly does rock. Released in 1999, at the time of this story, the disc’s eight studio tracks and four live cuts are lavishly doused with some of the lowdown nastiest guitar work ever to emanate from the formidable Mr. Gibbons. And XXX certainly is wild. At times the textures go all grainy and distressed, and beats occasionally loop off into the urban jungle, but the whole thing remains unmistakably ZZ Top. That little old band from Texas has become one of rock’s most enduring and strangest concepts. That’s the best way to put it. For all his prowess as a guitarist, Billy F. is first and foremost a conceptualist: a surrealist bluesman, a gentleman collector of cultural artifacts—clothes, cars, gadgets and sounds—that somehow all have a place in the world of ZZ Top.

“Three X” is the correct way to say the title band’s album. “It means many different things,” Billy says. As he points out, it could be taken as an acknowledgment that the year of its release marks ZZ Top’s 30th Anniversary. “It’s also the name of a great beer. It could mean poison, or a particular type of video entertainment…”

Billy’s mind works in unusual ways, generally moving in several different directions all at once. So it was arranged for me to spend an entire evening in his company, cruising Manhattan after dark in a black Lincoln Town Car. Who knows what insights might emerge?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Maybe we should start at the beginning of the evening, six hours earlier.

9:40 P.M., RIHGA ROYAL HOTEL, WEST SIDE

Billy is looking remarkably crisp for a guy who got off the plane from Texas just an hour ago. The Sharp Dressed Man personified, he’s wearing an immaculately cut blue designer suit, but his choice of accessories is…well… slightly left of GQ. There are loads of Mexican silver wrist bangles, a gold Rolls-Royce lapel pin, a bright red silk pocket square with white polka dots. The crowning glory is a most unusual red-and-green hat—part beret, part shower cap—crowded with 3/4-inch cloth nubs, like dreadlocks just starting to grow in.

“Our new trademark African hat,” Billy announces. “Funny dreadlock hat. Cowboy meets Africa.”

The hat ties in, albeit obliquely, with a song on XXX called “Dreadmonboogaloo,” a jaunty instrumental that successfully combines reggae, blues, techno, talk radio, flying saucers and a cheesy organ. It’s much like Billy’s wardrobe, a mad jumble of unlikely items that ought not to work together, yet somehow do. And as we leave the Rihga, Billy’s headgear is like a beacon, drawing every autograph hound on 54th Street. He patiently and cheerfully signs his name and poses for pictures. Then we’re off.

10:30 P.M., IRIDIUM JAZZ CLUB, WEST SIDE

Billy leans toward me in a conspiratorial manner: “I’m not gonna sit in. We’re just here to observe tonight, okay?”

Guitar legend Les Paul and his trio have a regular Monday night residency at Iridium. Billy smiles through yet another round of autographs and snapshots at the door. Then we’re shown to some seats. The club is crowded and the seating is communal, with audience members packed cheek by jowl at long rows of tables like something out of an ancient Norman banqueting hall. “No private table,” I find myself wincing. “This is gonna be weird.”

But it’s not. Within seconds, Billy is the best of friends with the guys seated near him—fellow Texans, it turns out. They’re soon comparing notes on Austin nightspots. Billy has a great ability to put people at ease. He can read them quickly and zero in on some area of common interest. As he’s interested in just about everything, this isn’t too hard. Everyone’s having a good time, but Billy is holding firm on one point:

“I’m not sitting in.”

Five minutes later, he’s up onstage with a Gibson Les Paul model strapped around his neck, the grinning object of “beard” jokes adlibbed by Les Paul himself. (Example: “Man, how’d you get that terrible fungus?”) Les is 84. Whether it’s a put-on or not, he seems to be only dimly aware of who Billy is. “Do you have a band?” he asks. “What are some of your songs?” Audience members pitch in. “Cheap Sunglasses”! “Sleeping Bag”!

“We do lots of songs about, um, anatomy,” Billy deadpans. “There’s one called ‘Legs.’ And we have another called ‘Tush.’ I guess we’re working our way up.”

The two guitar greats duet on a breezy 12- bar blues. The blues is a language that Billy speaks fluently in all its many dialects. In homage to his host, Billy tells the story of his most beloved Les Paul guitar, Pearly Gates, a sunburst ’59 Gibson Custom that looms large in ZZ Top lore. The narrative is pure Billy: fast paced, with many tangled threads. But it possesses all the essentials of a classic ZZ Top video. There’s a woman, in this case a friend of Billy’s who wanted to go to Hollywood and become an actress. There’s a car, a vintage yet barely roadworthy vehicle that Billy gives his friend for her journey westward. (The automotive gift is another essential ingredient in ZZ Top mythology. Gleaming car keys are invariably tossed to deserving protagonists.) The girl makes it to L.A., finds success, sells the car at way under market value and sends the money to Billy, who resignedly uses it to purchase the aforementioned ’59 Les Paul from a Texas farmer. Since the car had been named Pearly Gates, that becomes the guitar’s name, too. With this instrument, ZZ Top is founded. End of story.

Another 12-bar, a few more jokes and Billy’s back in his seat. All the facial hair in the world couldn’t conceal his ear-to-ear grin. Not gonna sit in, eh?

“Aw come on, it’s Les, man! How could I refuse?”

The L.A./Texas connection is an important one in Billy’s own life story. The son of a musician, he grew up around Hollywood, Las Vegas and Texas, the three places where his father worked most frequently. His family tree also includes noted film set designer, art director and studio exec Cedric Gibbons, creator of the Academy Award’s Oscar statuette. The art gene was passed on to Billy, who earned a degree in the subject from the University of Texas during the Sixties. Yes, the big ol’ beard and wild shit-kicker image is, in Billy’s case, something of a facade. Or rather, a kind of surrealist exaggeration of just one aspect of the man’s socio-musical background.

Billy tried combining visual art with rock and roll in his pre-ZZ band, the Moving Sidewalks, who were known for their elaborately psychedelic stage effects. Shortly after, he met Frank Beard and Dusty Hill. The drummer and bassist had already jelled as a rhythm section, having played together in countless Texas bar bands and the group American Blues, whose two albums, American Blues Do Their Thing and American Blues Is Here, are still a source of embarrassment for the duo. But nobody was embarrassed when Beard and Hill teamed up with Gibbons.

“I attribute a lot to Frank and Dusty,” Mr. Gibbons declares. “Their cohesiveness as a rhythm section. The real functioning cornerstone, the backbone, of any music is the rhythms. And in the case of XXX, Dusty and Frank have learned to create something, in many instances, by way of subtraction. There is a lot of spareness. I’m finding shiny spots where the guitar is actually living in the midst of their absence. That’s in the studio portion of the record. As for the live tracks, they’re full-on thrash-out stuff.”

Texas blues-based rock was still a novel concept in 1970 when ZZ Top’s First Album came out. But the band dug out a niche for itself through a series of hard-grinding albums and relentless touring. The thing broke through to a whole new level with 1975’s World Wide Texas Tour. That outing found Messrs. Gibbons, Beard and Hill performing onstage with an entire menagerie: buffalo, cattle, rattlesnakes, buzzards and other creatures native to the Lone Star State. It set ZZ Top miles apart from what by that point had become a glut of “southern boogie” bands. Rock and roll theme tours were still in their infancy. This one gave ZZ Top an ironic edge that reached out beyond their core rebel-yell audience. Was it a joke? The music certainly wasn’t.

A few years later, during the band’s extended 1977–79 hiatus, Gibbons and Hill both grew beards. Billy quickly turned this chance coincidence into another high-concept/low-comedy visual statement. Beards in place, the band the world now thinks of as ZZ top stepped forward in ’79 with an album called Deguello, recorded for their new record label, Warner Bros. Although the music was still deeply rooted in blues tradition, the visual presentation had more in common with what was being done by another bunch of art students, some guys named Devo, and the new wave of rock groups to which they belonged. ZZ Top’s lyrics also began taking on a kind of ironic undercurrent, as hinted by song titles like “Cheap Sunglasses” and “I’m Bad, I’m Nationwide.”

The phrase, “I’m bad, I’m nationwide,” Gibbons discloses, was co-originated by “Billy Lee Clayton, an old buddy of ours. He and I stumbled out of the Vulcan Gas Company, a nightclub in Austin. We’d just seen Freddie King. And we were searching for a phrase that would sum it up. He said, ‘Man he’s bad.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, he’s nationwide.’ The actual lyrics were devoted to another dear friend, Joey Long. He was this six-foot-tall, white Cajun guy who looked like Wolfman and played the meanest swamp guitar ever. He had a lovely wife named Barbarella, who drove their series of Cadillacs. He didn’t even have a driver’s license. But that made it all the more beautiful. He was definitely bad, and nationwide.”

The advent of MTV in 1980 was like a dream come true for Billy, a brand-new vehicle for developing the visual/conceptual side of ZZ Top. “There’s something real valuable in what MTV managed to bring to moment-by-moment living,” Billy muses, “if you so chose to enter the world of the surreal. Salvador Dali, Picasso and the rest of them were right when they said that some day art will not be inaccessible; art will be in our hands.”

Aided by a string of memorable video clips and a new techno-enhanced sound, ZZ Top enjoyed its greatest commercial success ever with 1983’s Eliminator, ’85’s Afterburner and singles like “Gimme All Your Lovin’,” “Sharp Dressed Man” and “Legs.” ZZ Top were on top, while southern blues–based contemporaries like Lynyrd Skynyrd or .38 Special were names you just didn’t hear anymore. The Eighties were a great time for ZZ, but how does Billy rate the decade in general?

“I think I got it in perspective just a little while ago,” he grins. “I was watching the video for Talking Heads’ ‘Burning Down the House.’ You know the one where they’re projecting this image of David Byrne’s head on this highway with white lines going up the middle? Looking at it, I realized that all those white lines are going straight up his nose. That just about sums up the Eighties, don’t you think?”

1:35 A.M., RESTAURANT FLORENT, MEAT PACKING DISTRICT

“Man, that’s tight!” Billy is grooving to the techno futurist sounds of Photek blasting from the stereo system in this all-night boho hipster diner. An insomniac, round-the-clock kind of guy, Billy knows the all-night places in many of the world’s great cities. He comes to this far west downtown Manhattan spot for the music as much as the food. He soon has a decidedly post-modern-looking waitress up on a chair, retrieving the CD that’s been playing so she can write down the track names for Billy. It’s no secret that ZZ Top’s guitarist is an avid fan of electronic and dance music. No one delights in the seeming incongruity of this more than Billy himself. With considerable relish, Billy tells the story of how he got into a recent soldout Chemical Brothers show just because the guy at the door couldn’t believe that someone in ZZ Top would even want to go near a Chemical Brothers gig.

“You mean you’re into this?” said the astonished doorkeeper, eying Billy’s long beard. “This I gotta see. Come on in.”

Gibbons and ZZ Top have long had a great knack for incorporating contemporary rhythms and sounds into their classic bluesbased approach. They used heavily sequenced Eighties machine rhythms on Eliminator and Afterburner as deftly as they fold drum-and-bass beats into XXX’s “Dreadmonboogaloo.” Another track, “Crufcifixx-a-Flatt,” crosses boldly onto hip-hop’s rhythmic turf.

“The studio sessions for XXX unfolded at Foam Box Recording, our private room in Houston, Texas,” Billy relates. “And we’re right next door to the famous rap studio, John Moran’s House of Funk. He does Scarface, the Geto Boys, Destiny’s Child, Cash Money…all these great things that are having such a tremendous impact in Houston. So we started hanging out over there. In fact, we wound up mixing our tracks at the House of Funk. During that, we were still finding time to go back in our studio and cut new tracks. So we couldn’t help but be influenced by our socializing with the rappers. They were so gracious in doing that streetwise thing with ZZ. And we were willing students.”

XXX, Billy continues, “is the result of almost a full year doing the daily studio grind out at Foam Box. There were hours and hours of jam sessions. And the best of that was taken and reassembled using Pro Tools. ZZ Top have, in my humble opinion, one great true trio record: our last album, Rhythmeen, which had very few overdubs or punch-ins. That’s about as straight ahead as it gets. But on this new record, we have made great strides and taken great liberties with some wonderful drum loops and some great textural background-y things. And its all aimed at giving the guitar player a nice heavy platform to feel solid with. When you get that much to stand on, brother, it’s pedal to the metal. I mean stand on it.”

With all that digital cutting and pasting, there are moments when XXX takes on a kind of Tom Waits scrapyard sensibility. “Tom Waits is one of my all-time heroes,” Billy confirms. “We learned a long time ago that we were better off attempting to emulate Howlin’ Wolf than pretending to be the next Bob Dylan. Yet there are just some charming dramatics in a handful of really visual lyricists like Waits, and that gets us aimed in the right direction, lyrically. Some of it is nothing more than backroom poetry. ‘Crucifixx-A-Flatt’ is our religion-meets-automotive- safety song but attempted from that Tom Waits’ point of view. Like, you know what a crucifix is, and most people know what a can of Fixx-a- Flatt is, but Crucifix-A-Flatt is that gift from God at those times when life hands you nothing but a lonely road and a flat tire. It’s that safety factor.”

Other songs on XXX are more straightforward, like the album’s first single, “Fearless Boogie.” “It’s our best work drawn from that Jimmy Reed tradition,” Billy says. “That little Eddie Taylor [American blues guitarist/singer and friend of Jimmy Reed] hammer-on note is more than an afterthought; it was directed to be just that. It brings into focus the fact that ZZ Top still manage to hold onto that barroom tradition from whence the band originated. It’s a legitimizing factor that balances out some of the craziness on the rest of the album.”

Another key influence on XXX was Jeff Beck. ZZ Top caught one of Beck’s shows at New York’s Roseland. Afterward, they went backstage. “Jeff’s new thing is champagne only backstage,” Billy says. “No beer. No water. Nothing but champagne. Everyone was in a great mood. It was very lively back stage. But suddenly a sort of lull fell over the room. In the awkward silence I suddenly found myself blurting out, ‘Hey Jeff, wanna play on our new album?’ No sooner were the words out of my mouth than I became painfully aware of what a dumb remark that was. Beck doesn’t play on anybody’s album. Not Michael Jackson. Not Prince. Nobody. So to try and save the situation, I said to Jeff, ‘But I don’t want you to play guitar. I want you to sing.’ Beck says ‘Brilliant!’ I don’t know if he was being gracious and rescuing me from my faux pas or if he really meant it. Jeff hasn’t really sung all that much on record. But the next day his manager said to me, ‘He’s really serious about this.’ ”

So Beck wound up overdubbing backing vocals onto the live track, “Hey Mr. Millionaire.” “I went up to Jeff’s hotel room with a Sony MiniDisc recorder and one of those little stereo microphones that go with it,” Billy continues. “And we recorded the vocal right there in the hotel room. The engineer for our album had told me, ‘Just get something on tape and we can insert it using Pro Tools. We can pitch-correct it and time-stretch it if we need to.’ So I just had to get him to sing his vocal part in the hotel room. ‘You know how much trust this entails?’ Jeff said to me. ‘Because I can’t actually sing, you know.’ ”

Beyond this vocal performance, Jeff Beck’s influence can be felt on some of Billy’s guitar playing for XXX as well. There’s a whiff of Beckism in his phrasing, note bends and use of echo.

“Of course, “ Billy concedes. “Beck twisted our minds at that show. He just takes it in his stride and moves onto the next gig, no big deal, while everybody else is still scraping themselves off the floor saying, ‘Wow, man, that was tough stuff!’ So we raced out to get the new Jeff Beck album. And it did influence us quite a bit.”

2:15 A.M., RESTAURANT FLORENT

“Let’s see, give me four of the vegetarian chilis, six of the mushroom salads…” Now Billy’s ordering some food to go. It’s another one of his peculiarities. He likes to order up tons of food. Around him, there are often numerous people rushing off in different directions to fulfill detailed sets of instructions—culinary and otherwise—issued by Billy. Somewhat sheepishly, he tells me how he once commandeered cartons of comestibles at the airport. He knew the food on the plane would be wretched. But once he got onboard, he fell asleep, not eating a thing.

To tell the truth, Billy is something of a pack rat. A hoarder. When he leaves a restaurant or club, he’ll invariably line his pockets with matchbooks, postcards, anything that’s there for the taking. He carries a miniature camera with him to capture scenes that seem important to him at the moment. It could be the inside of a store. Or a street corner. Just about anything. Back in Texas there are said to be eight warehouses filled with ZZ Top memorabilia: stage clothing, props, equipment…

2:30 A.M., GEM SPA, ST. MARK’S PLACE, EAST VILLAGE

Apparently, Billy’s hoarding instinct extends to information as well as material objects. Here he is at one of New York’s best-stocked newsstands buying a dozen hotrod magazines and a few surf mags, having decided that he’s already read all the pertinent music magazines on display. If nothing else, all this voracious reading makes Billy a great conversationalist. Architecture, macrobiotics, obscure blues recordings, automobiles, the design and manufacture of sunglasses… Bring up a subject and he’s just about certain to be in possession of the relevant facts, figures and a handful of original opinions.

3:35 A.M., RIHGA ROYAL HOTEL

The evening winds down where it began, at the bar in Billy’s hotel, which is now deserted. As often happens at this time of the morning, the conversation turns to stupid stuff like, will there be blues in the 21st century?

“Of course,” says Billy, whose devotion to the genre is profound.

And does he have a disaster plan in the event that, as predicted, a computer bug shuts down power grids around the world at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve 2000?

“Well, we have purchased some Baygen radios,” he replies, referring to the handcranked transistorized devices. “They have a rechargeable battery that can provide about a half hour before it needs to be recharged again. The fancier models have a light as well, which means you can have half an hour of light and, during that time, listen to your favorite music. So that, while we might experience a blackout in the new century, we can still have the blues.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“We hadn’t really rehearsed. As we were walking to the stage, he said, ‘Hang on, boys!’ And he went in the corner and vomited”: Assembled on 24 hours' notice, this John Lennon-led, motley crew supergroup marked the beginning of the end of the Beatles

“I pushed myself to down-pick faster and make the riffs more aggressive. Maybe it’s the old man in me struggling to feel young and fighting back against aging”: How Killswitch Engage went to thrash metal bootcamp to deliver their face-ripping return