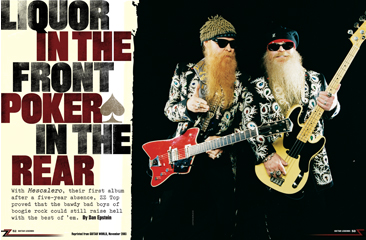

ZZ Top: Liquor in the Front, Poker in the Rear

With Mescalero, their first album after a five-year absence, ZZ Top proved that the bawdy bad boys of boogie rock could still raise hell with the best of ’em.

It’s a gray March afternoon in Houston, Texas. Outside, the rain is coming down in chilly torrents, but inside a hotel suite near the city’s Galleria shopping center, hometown heroes ZZ Top are basking warmly in the toasty glare of a TV crew’s lighting rig. Scheduled to play Rodeo Houston tomorrow night, drummer Frank Beard, bassist Dusty Hill and guitarist Billy F. Gibbons have assembled to good-naturedly answer a few questions about the a three-week rodeo/music event for the local news media. “You’ve gotta put on a good show in your hometown,” Dusty says. “Otherwise, you hear about it the next day at the gas station!” When the interviewer asks them the secret of their success, Gibbons doesn’t miss a beat. “Tone, taste and tenacity,” he rumbles from behind his omnipresent beard and shades. Go ahead—name another rock band that’s stayed together without a single lineup change for as long as ZZ Top. You can’t; even U2, who are generally viewed as the model of longterm band unity, first took the stage almost eight years after Billy, Dusty and Frank’s inaugural jam at a 1969 Halloween party. Put it down to tone, taste, tenacity or anything else you like, but ever since that day, the self-styled “Little Ol’ Band from Texas” has consistently offered up a deliciously twisted, gloriously distorted spin on Lone Star State blues. They’ve incorporated various technological advances along the way, yet they’ve typically ignored the prevailing fads and trends of the moment.

Mescalero (RCA), ZZ Top’s sprawling 16-track album from 2003, adds its own unusual chapter to the ongoing sonic saga. Produced by Billy F. Gibbons at his Foam Box Recordings studio in Houston, the album has a little bit of something for every ZZ Top fan, whether they met the band on 1973’s Tres Hombres, 1983’s Eliminator or 1999’s XXX. “It has some early style, some middle style and then some wild style,” Billy says with a smile. You want some old-school roadhouse crunch? Dig the low-down boogie of “Liquor,” the raunchy “Buck Nekkid” or the greasy cover of Lowell Fulson’s “Tramp.” Need a little blues to go with that heartbreak? Try the tear-jerking lament “Goin’ So Good.” Have a taste for some futuristic, industrial-flavored beats? Help yourself to the goofy “Me So Stupid” or the driving instrumental “Crunchy.” And then there’s tracks like “Mescalero,” “Two Ways to Play,” “Punk Ass Boyfriend” and “Piece,” on which ZZ Top sound both more nastily fuzzed-out and more electronically hotrodded than ever. In fact, if pressed for some sort of shorthand to sum it all up, you could do far worse than to describe Mescalero as “ ‘Tush’ Goes Techno.”

“Hey, not bad! Can we use that?” Billy says, as he and Dusty sit down with Guitar World to discuss the record. According to the guitarist, the album’s genesis began with one of the band’s previous European tours, where the boys were subjected to a steady stream of electronic sounds in the local clubs and watering holes. “Techno is rockin’ over there,” he says. “They do it in a different kind of way than what we might consider it from stateside. It’s a little more heavy. And Dusty’s kind of pushed me off in a direction. He said, ‘Put this into your brain. Think early-style ZZ with the European thang.’ ”

“‘Techno’ is a word almost like ‘disco,’ ” Dusty adds. “It’s got a bad connotation to it—you know what I mean? But there’s cool techno, stuff that has more of an element of rock and roll to it. Plus, when we put our hands on it, it gets dirty. Which, you know, is good, as far as we’re concerned.” Dirty sounds certainly do abound on Mescalero, thanks in part to an odd German guitar called the Teuffel Birdfish. A lightweight aluminum instrument with no headstock, three moon-shaped humbucking pickups and interchangeable “tone bars”— resonators—the Birdfish looks more like a work of postmodern sculpture than a functional ax.

“This eccentric German guy makes them in some hidden-away barn in the dark part of the Black Forest,” Billy explains. “But there was a Teuffel rep based in Orange County, California, and he knew that ZZ Top—both Dusty and I—had an affinity for the odd and unusual. And I’m thinkin’, Well, I’ve heard that before… But he was like, [in Texas approximation of German accent] ‘Oh, Billy, let me zend you zomething!’ Well, we opened the box, and I said, ‘What is this? Whatever it is, I like it!’

“Dusty and I experimented with them, just out of curiosity. But they had our kind of sound right out of the box. And we used them on four tracks—‘Mescalero,’ ‘Two Ways to Play,’ ‘Buck Nekkid’ and ‘Piece.’ They’re quite comfortable, they stay in tune great. It’s adjustable in every way that you’d want: the pickups go up and down, they go forward and back, and you can set your pickup position to the 16th of an inch. It really shines on ‘Mescalero’ because of that dirty, raunchy tone. I defy any other instrument to get that crazy. It would take a line of 50 Fuzz-Tones!”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Of course, it wouldn’t be a ZZ Top album without the presence of Pearly Gates, Billy’s legendary ’59 Les Paul. “Pearly’s on just about everything on Mescalero,” Billy says. “Pearly Gates is the cornerstone of sound, and from all that, others will be judged. I also used an old Gretsch that Bo Diddley gave me, and a ’51 black pickguard Esquire that I think I used on ‘Tramp.’ It was tuned down to low B, which almost rendered it unusable, but it lended that heaviness to it. It’s a strange sound—strange in a good way, I suppose!”

For a band so steeped in blues history and lore, ZZ Top have surprisingly few covers of classic blues numbers in their discography. But the lure of “Tramp,” originally recorded in 1966 by Lowell Fulson—and later covered by numerous artists, most famously as a duet by Otis Redding and Carla Thomas—simply could not be denied.

“I heard it on the radio in Los Angeles during one of the Sunday afternoon blues hours,” Billy explains, “and I couldn’t forget it. It just stuck and stuck and stuck.” After kicking it around a few times during prerecording jams, the band decided to try tracking it. “It just became so much fun to play, we thought, Hey, let’s give this a run!” Dusty says. “Through the years, we haven’t done a lot of other people’s stuff, but occasionally we’ll do something. And with Billy’s voice, it just seemed right.”

Adds Billy, “Lowell Fulson was so great, but somewhat underrated in the grand scheme of who gets mentioned first. You’ve got Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, TBone Walker, Freddie King, Albert King. But where’s Lowell? He was a talent; he could deliver. His records on Kent have a beautiful, warm sound. ‘Black Nights’? That’s some great, great stuff.”

In addition to his Tueffel Birdfish bass (allegedly the only one in existence), Dusty used his trusty early Fifties Fender Telecaster bass on the album, along with an offthe- rack Sixties Jazz Bass reissue. “Dusty’s the only bassist I know that’s got a built-in Fuzz-Tone in his finger,” Billy says, then laughs as Dusty proudly displays his right index finger. Nicknamed “the Pleaser,” the stubby digit hasn’t bent in decades, the result of a football injury in his younger days. “Whatever I’m playing, once I put ‘the Pleaser’ on it, it seems to change the sound anyway,” Dusty says with a shrug.

Dusty’s studio rig, an old Ampeg SVT head with an 8x10 cabinet, made its presence felt during the Mescalero sessions in more ways than one.

“To get a little separation in the recording room, the speaker cabinets were crammed into the corner, turned in to the wall,” Billy says. “Now, our next-door neighbor shares a common wall. Granted, it’s a pretty significant firewall, but the way Dusty plays… Our neighbor is a photographer, and he basically does glamour work. One day he came over and said, ‘So, what’s up?’ And I said, ‘We’re basically just reviewing the tracks, doing a little catch-up and housecleaning. Why do you ask?’ And he said, ‘Because I’ve got these great-lookin’ girls comin’ in, and they always work better when that ‘boom’ comes through the wall!’ ”

“It really shakes their tiara,” Dusty says, grinning.

“I’m glad you said that,” Billy says. laughing. “I was gonna say something else, but ‘tiara’ works.”

Hang out in Houston with Billy F. Gibbons for any decent length of time and you’ll come away with a sense of what it must be like to keep company with royalty. Everywhere Billy goes in H-Town, people call out his name, greeting him like an old friend. Middle-aged men come to his table, hands trembling, to shyly request an autograph; attractive ladies drape themselves around his lanky figure, playfully asking when he’s going to marry them. Through it all, Billy remains remarkably gracious, never pulling a star trip or being anything less than accommodating. It’s been said that no one in rock and roll truly enjoys his fame more than Billy F. Gibbons, and there’s little in his manner that would appear to contradict such a statement.

There are, however, times when the patience of even the most stoic individual can be sorely tested. The night before ZZ Top’s appearance at Rodeo Houston, Guitar World, Billy and a couple of his pals repair to a local cantina for a post-rehearsal round of beer, margaritas and chicken enchiladas. It’s almost closing time, and the place is empty, save for a few customers and one exceedingly drunk mariachi, whose filmy eyes light up as soon as Billy walks through the door. Though the guitarist is too soused to play, let alone drive home, he insists on performing a number or two for Billy and his crew. Billy requests the traditional Mexican ballad “Volver, Volver,” taking the high vocal harmony as the musician happily fumbles his way through the song.

When the performance concludes, Billy’s cohorts offer polite applause, silently hoping that the mariachi will return to his barstool. Instead, fired up by the positive reception, the man begins to yammer excitedly in rapid-fire Spanish, oblivious to the fact that not even Billy, the one person at the table with decent Español skills, has any idea what he’s talking about. Then, satisfied with his monologue, the guitarist breaks into a rendition of “Guantanamera” that can only be described as “grinding.” As his audience looks on in wordless horror, a steady stream of drool begins to pour from the right corner of his mouth while he plays. The saliva waterfall first hits the body of the guitar, then splashes straight into the fresh basket of tortilla chips sitting on the table. “I think these oughta be hermetically sealed or something,” Billy says, chuckling as he gingerly moves the chip basket to the next table, as the restaurant manager finally escorts the sodden guitarist back to the bar. “But what I really wanna know is, what kind of tequila was that cat drinkin’?”

For all his elemental sang-froid, you’ve gotta wonder sometimes if the guitarist’s selfeffacing sense of humor—his business card reads “Gibbons: Friend of Eric Clapton”—and eccentric personal style hasn’t somehow kept Billy F. Gibbons from getting his total due as a musician. To much of the world, Billy is more of a cartoon character than a guitar hero, but his searing approach to electric blues is certainly as unique (and nearly as influential) as that of Clapton, Keith Richards or the late Stevie Ray Vaughan.

Mescalero represents yet another milestone in Billy’s endless quest to refine his saturated, instantly recognizable tone. “I’m not above taking a moment to experiment with this and that,” he says, rattling off a list of effects that includes Vari-Drive, Real Tube, Austone and Expandora distortion units, some ancient DeArmond tremolo pedals and “that Danelectro wah-wah that looks like a car—that’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen!” But for the most part, Mescalero’s sleazy, splooge-encrusted guitar tones are as much the product of a happy accident of physics as they are of well-chosen stomp boxes. Or maybe we’d better just get out of the way and let the man explain.

“I’ve got a nice little 2x10 Marshall that was put together by Brent Magnano’s outfit, Guitar Oasis,” Billy says. “For convenience, a ‘Plexi’ head was stuffed into an old mini-Marshall cabinet; there was just enough space to squeeze two 10-inch speakers into it. That’s panned hard right on the recording, and then we’re using the Marshall JMP-1 pre-amp—it’s got a little 12AX7 tube in it—and that’s direct-signaled to the left side, hard-panned left.

“While recording, we kept hearing what we thought was a delay, a little bit of slapback. But it wasn’t even—some notes were closer together than other notes. And we looked and we searched; we chased all the signal lines down, and we didn’t even have a delay in the line. What we suspect was occurring was a simple law of physics: the paper speakers were making their excursions outward and inward, while the JMP-1 was hardwired. Now, electrons travel much faster down the wire than this primitive method of sound reproduction; the paper was responding slower, but the high notes were close together, and the low notes got wider apart. So it’s this organic delay effect. It weaves all over the place—it’s smeary. We’ve noticed that it even changes from guitar to guitar, particularly Fenders. Because of their longer scale, they have a tighter, treblier sound, and of course it’s reflected in the amplifier end of things. Man, just when you think you know it all, something jumps up to say, ‘Nope, it’s gonna change on ya!’ ”

According to Billy, humidity—something that Houston has no shortage of—also played its part in the recording. “The quality of the air surrounding a microphone can really affect the sound,” he says. “You say, ‘What’s different today?’ Well, it’s 100 degrees and 80 percent humidity; the air is rich, and then if that changes, guess what? The response of that speaker and diaphragm of the microphone, it’s all different, because the air between ’em is different. It’s amazing. It can drive you crazy—good crazy.

“Maybe that’s what contributes to the magic and the mystery that differentiates Texas tone from anyplace else. Particularly on the Gulf Coast—you get players from the Mexican border, all the way through Louisiana and Mississippi. You get in a hot rod and follow Interstate 10 until it ends over in Florida. As long as you stay south, it’s gonna be fat and sassy.”

It’s nearly showtime at Houston’s Reliant Stadium, an edifice so monumentally hulking, it positively dwarfs the neighboring Astrodome. This is the eighth night of this year’s Rodeo Houston, but most of the 60,000- plus people in attendance seem as if they could care less about the evening’s calf-ropin’ and bronc-bustin’ competitions. They’re here to see ZZ Top, who are playing back in their hometown for the first time in 12 months.

After country artist Lee Greenwood gets the crowd pumped with a solo performance of his “God Bless the USA,” set to a backdrop of Space Shuttle and U.S. Air Force footage, Billy and Dusty emerge onto the revolving stage in rhinestone-studded serapes and 10-gallon hats and promptly kick the shit out of a hit-packed 15-song set. Billy plays his Bo Diddley Gretsch for most of the evening, then whips out Pearly Gates for a couple of numbers—only it’s not actually the fabled ’59 Les Paul but rather a hollowedout reissue model that, Billy proudly tells Guitar World, “weighs less than a Martin acoustic.”

“We steamed off the top and went for it,” he says. “I was like, ‘I don’t want a speck of sawdust that isn’t necessary.’ We did four of ’em—standard, right-off-the-rack Gibsons. There was one of the Gibson Les Paul reissues that was quite pricey, but I knew that we were taking a chance on totally trashing them anyway, so we bought the cheap ones.”

In sound and attitude, ZZ Top still come off more like a garage band than a classic-rock institution. Not surprisingly, they’ve been heartened by the emergence of newer, rawer bands like the Hives, the Vines and the White Stripes. “What they’re doing feels closer to the heart of how we started than anything else out there,” says Dusty, who paid his garage-band dues with Frank Beard in the American Blues before they hooked up with Billy, who had been playing with the Moving Sidewalks. “Just bangin’ for it and gettin’ complaints from neighbors, you know? I mean, you’ve gotta get complaints from neighbors, or you ain’t doin’ it right.”

“All of the ‘the’ bands, they’re poignantly expending their personal energy toward ‘getting it right,’ ” says Billy, nodding sagely. “What ‘right’ is, we don’t know. But when you feel it, it’s good. And these guys are doing it.”

ZZ Top are doing it as well, and they’ll probably continue to do so until the Grim Reaper pries their vintage axes from their cold, dead hands. “We’re still the same three guys, playing the same three chords, enjoying it all,” says Billy. “That’s how we started. We’ve always said, ‘Make it loud, and it’ll be fine.’ ” And it always is.