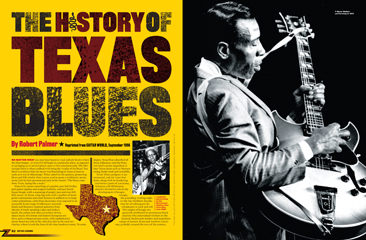

ZZ Top: The History of Texas Blues

Guitar World recounts the history of the Texas blues, focusing on famous guitarists from Leadbelly to ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons.

No matter what you may have heard or read, nobody knows where the blues began—or even if it did begin in a particular place, as opposed to springing up in several places more or less simultaneously. The Mississippi Delta is often credited with being the “cradle of the blues,” but there is evidence that the music was flourishing in Texas at least as early as it was in Mississippi. When asked for his opinion, pioneering blues and folk scholar Alan Lomax used to quote a traditional, anonymous lyric he had encountered early in his travels: “The blues came from Texas, loping like a mule.”

Blues is by nature something of a gumbo: part field holler, part guitar ragtime and songster balladry, and part barrel-house boogie, with a seasoning of gospel, jazz and even hillbilly music. In Texas, a big, big state with a number of immigrant communities and small farmers in addition to its large cotton plantations, early blues musicians were exposed to an unusually broad range of influences: mariachi bands and flamenco-inspired guitarists from Mexico; French-speaking Cajun and Zydeco bands; the polkas and other accordion-driven dance music of German and Eastern European settlers; and a widespread jazz scene, with sophisticated music heard not only in the cities but also in the rural territories, where it took the form of old-time hoedown music. To some degree, Texas blues absorbed all these influences, and the blues was itself a prime ingredient in later Texas styles such as Western swing, honky-tonk and rockabilly.

Texas’ blues pedigree is unsurpassed, and the Lone Star State, along with its bordering territories (parts of Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma), played a formative role in the development of boogie-woogie, the pounding, rocking eight-to-the-bar rhythmic foundation for all subsequent developments in rock and roll. The origins of boogie are generally attributed to anonymous black pianists who entertained workers in the isolated, backwoods lumber and turpentine camps of eastern Texas and western Louisiana, probably around the turn of the century.

A traveling pianist and songwriter from New Orleans, Clarence Williams, reported hearing a Texas pianist playing boogie-woogie bass figures in Houston in 1911, more than 15 years before the first boogie-woogie recordings. (The Texas pianist George Thomas was the patriarch of a piano-playing family that included early recording artists Hociel and Hersal Thomas and their sister, better known as the classic blues singer—and Bonnie Raitt idol—Sippie Wallace. In 1917 or 1918, another pianist, Sammy Price, heard blues guitarist Blind Lemon Jefferson playing bass-string boogie riffs. The term Jefferson knew, however, was “booger rooger,” which was something like an all-weekend house party, what East Texas Cajuns called a “la la.” You can hear Jefferson’s jamming, loose-limbed approach to the “booger-rooger” rhythm in the final choruses of “Easy Rider Blues,” his version of the pre–World War I Texas standard. As with so much of American music’s history, nobody knows for sure whether boogie-woogie was invented by pianists and later adapted to the guitar, or the other way around. However it went down, it probably went down in Texas.

THE FIRST GUITARISTS

Guitars seem to have found their way into the hands of black musicians in Texas earlier than in other parts of the South. The long border the state shares with Mexico meant there was widespread contact with Spanish-speaking immigrants, whose culture has cherished the guitar since the Moors brought prototypes to Spain in the Middle Ages. Centuries later, back in Texas, the first wave of black guitarists we know about had already developed their own style and repertoire well before the initial wave of popularity for the blues. Huddie Ledbetter, better known as Leadbelly, roamed the countryside playing a rolling bass-heavy style of 12-string guitar (then a novel Mexican import) and singing narrative ballads, hoedown tunes and other dance music that predated the blues. “Texas” Henry Thomas was a hobo who ferociously strummed his guitar while blowing on a set of cane panpipes that was rack-mounted around his neck, like a harmonica.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Thomas left an impressive body of recordings, including “Bull Doze Blues,” from which Canned Heat derived their 1969 hit “Going Up the Country.” Of all the Texas songsters (archetypal wandering bluesmen except that they performed more ballads, breakdowns and ragtime than blues), Mance Lipscomb was one of the longest lived and best loved. Unlike Leadbelly and Thomas, he generally stayed in one spot and farmed rather than brave the juke joints and barrelhouses, where murder and mayhem could be counted on to spice up most any Saturday night.

During the first few decades of the 20th century, blues slowly eclipsed the old songster ballads and hoedown tunes as the rural dance and entertainment music of choice. In most of the South, there were considerable social as well as musical barriers separating blues musicians from those who played jazz or sang gospel. Blues was “country,” associated with the “down and out”; jazz musicians considered it musically moronic, and pious churchgoers deemed it the devil’s music.

Texas, once again, did things differently. From the beginning, Texas blues and jazz enjoyed a fruitful relationship, one that worked to the advantage of both. Even the most unreconstructed, musically primitive bluesmen, such as the influential singer Texas Alexander, often recorded with a sympathetic jazz player or two as featured soloists. The jazz musicians, for their part, didn’t share their peers’ disdain for the blues; in fact, jazz bands from Texas and Oklahoma largely built their reputation playing loosely arranged, rhythmically compelling jump blues. This was as true of the Blue Devils, Twenties precursors of the original Count Basie band, as it was 20 years later, when Houston’s Milt Larkin Orchestra introduced a whole new generation of honking, big-toned Texas saxophonists—bluesmen all.

BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON

But when it comes to blues, Blind Lemon Jefferson was the most influential artist Texas produced until the post–World War II arrival of seminal electric guitarist T-Bone Walker. As early as 1915, Jefferson was known around Dallas and in the surrounding countryside as an itinerant street singer. Beginning in 1926, he enjoyed a string of hit records that continued, off and on, until his death in 1929. Nowadays, Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and other Mississippi Delta bluesmen are the best remembered of Lemon’s near contemporaries, but he was arguably a more significant blues artist than any of them. According to blues historian Steve Calt, a Patton champion and biographer, Blind Lemon Jefferson was “as important within the scheme of blues as Elvis Presley is to rock” and “the most famous males blues singer who ever lived, rivaling Bessie Smith for popularity among record buyers of his time.”

Many rural bluesmen habitually drop a beat or a bar from, or add a half bar or more to, the standard 12-bar verse, resulting in actual verse lengths ranging from 11 to 13 and a half bars, often in the same tune. On first impression, Jefferson’s playing was even more anarchic that that: while singing, he would strum quiet chords or softly mark the beat, but his guitar fills, generally tumbling, single-note lines inserted between vocal verses, were liable to meander almost anywhere. Calt describes these fills as “impromptu-sounding riffs of no fixed order or duration.” This edge-of-your-seat approach to improvisation is what makes Jefferson classics like “Match Box Blues,” “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” and “That Black Snake Moan” perennially rewarding and surprising.

In effect, Jefferson developed and popularized “lead guitar” as a style of blues accompaniment. T-Bone Walker, who listened to Jefferson and followed him around Dallas as a youth, later amplified the single-note lead lines he’d inherited. Walker’s combination of melodic invention, bluesy string bending and jazz-flavored chord voicings inspired virtually every blues-based guitarist who’s come along since, including Delta-bred stylists as influential in their own right as B.B. King and Robert Jr. Lockwood.

ELECTRIC TEXAS

Texas musicians took to the electric guitar as rapidly and enthusiastically as they had taken up the guitar itself at the beginning of the century. Eddie Durham, a guitarist from San Marcos, Texas, made his first “amplified” guitar in the early Thirties, using a tin pan as a resonator. Soon he had graduated to homemade pickups, playing through radios and phonographs and leaving a trail of burned-out appliances behind him. When DeArmond came out with its pioneering guitar pickup in the Thirties, Durham was among the first to use it. In 1937, he met another young local guitarist, Charlie Christian, and they traded amplification arcana.

In parallel to these developments, amplified guitar and lap-steel guitar quickly made inroads to the Western swing music scene. The most startling of the early electric steel players was Bob Dunn, a featured soloist with Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies. Dunn played pedal steel like a modernist-leaning trumpeter: isolated bursts of notes, daring harmonic choices, unpredictable phrasing that could be jagged one minute and flow like honey the next. By the end of the Thirties, Milton Brown’s band had broken up (following the leader’s death on the highway), and the best-known, most influential Western swing pickers were guitarists Eldon Shamblin and steel guitarist Leon (“Take it away, Leon!”) McAuliffe, both of whom were featured with Bob Wills. Nobody who’s heard Bob Dunn’s twisted steel lines come cascading out of a charming piece of Milton Brown square-dance hokum can forget the experience. The guy was one of a kind, and his few recording must only hint at his weird genius.

After World War II, electric guitars and guitarists continued to proliferate, challenging and eventually supplanting the saxophone as vernacular music’s principal solo voice. Iconoclastic, quasi-freeform blues guitarists in the Blind Lemon tradition—Lightnin’ Hopkins, Frankie Lee Sims, the Black Ace and others—plugged in and rocked the juke joints and taverns, but the T-Bone Walker mode was dominant, and in the Forties and Fifties Texas produced an astonishing number of influential, wildly kinetic and competitive lead guitarist/ blues singers. Even a limited list would have to include iconic figures such as Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Pee Wee Crayton, Freddie King, Albert Collins, Johnny Copeland, Lowell Fulson, Cal Green (Hank Ballard and the Midnighters’ axman), Clarence Garlow, Roy Gaines and Goree Carter (whose 1949 “Rock Awhile” is a worthy candidate for “first-ever rock and roll record”), not to mention legendary session guitarists such as Wayne Bennett and Clarence Holloman and lap-steel playing bluesmen Sonny Rhodes and Hop Wilson. Most of these guitarists fronted bands with a small horn section of saxes and brass as well as the standard piano, bass and drums. The close connection between blues and jazz in Texas was still much in evidence.

Artists such as these often performed locally, bringing their shows not just to cities and towns but also to rough, rural dance halls. This rich musical environment had everything to do with the growth and development of younger musicians coming of age in the Sixties. For electric guitarists Johnny Winter, Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan and Doug Sahm, as well as for acoustically minded pickers like Willie Nelson and Townes Van Zandt, blues was much more than a musical language acquired from obscure phonograph records; it was a language they shared with the form’s mostly black creators, often from early childhood. As a result, Texas guitarists seem to have a genuine, deeply rooted feel for the blues, whatever their color. When Stevie Ray Vaughan soared on minor-key blues changes, or when Van Zandt picks and sings one of his 10-and 11-bar originals, there can be no doubt this is the blues. We shouldn’t be surprised: from Bob Dunn to honky-tonk’s Lefty Frizzell to rockabilly’s Sleepy LaBeef, Texas guitarists have been playing and singing idiomatic, natural blues for generations.

BIG STATE, BIGGER QUESTIONS

Why is this significant and substantial musical culture still relatively little known and underappreciated? Texas was an incubator— perhaps the incubator—for blues and boogie-woogie at the beginning of this century, and later for electric blues, honky-tonk and important developments in country swing and rock. Yet we hear and read much more about the Delta, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. In part, Delta blues has attracted fans and boosters with its rawer and more in-your-face approach, which features aggressively driving, syncopated cross-rhythms. And Delta music has a potent mystique— hellhounds on your trail, the blues and the devil walking side by side, selling your soul to the dark man at the crossroads. To some degree, this mystique was calculated from the very beginning: early bluesmen such as Tommy Johnson, Son House and Muddy Waters knew that invoking hoodoo not only played to the beliefs and fears of their audience in the joints but also helped them to craft an image. And it sold records.

Texas has its own brand of hoodoo, and it has seeped into tunes like Hop Wilson’s odes to his baby’s black-cat bone. But the deep, heavy, serious metaphysical baggage that comes with so much Delta blues is rare in Texas, where blues is, above all, music for entertainment and dancing, or for chronicling the ups and downs of day-to-day experience, as in the autobiographical blues of Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Delta blues is a kind of sacred music, opposed to the church but espousing its own African-rooted spiritual values. In Texas, on the other hand, blues tends to be resolutely, unapologetically secular, sensuous, even carnal, like rock and roll. The blues scholars may not all get it, but musicians do; there isn’t a blues guitarist alive who hasn’t picked up something from T-Bone Walker or one of his disciples, just as no jazz guitarist for decades has remained untouched by the innovations of Charlie Christian. Among Texas guitarists, musical standards are particularly high, which is why you’ll find even B.B. King worshipping at T-Bone’s feet. That Texas blues just keeps loping along, but these days it’s more like an express train than a mule.

“It's like saying, ‘Give a man a Les Paul, and he becomes Eric Clapton. It's not true’”: David Gilmour and Roger Waters hit back at criticism of the band's over-reliance on gear and synths when crafting The Dark Side of The Moon in newly unearthed clip

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer