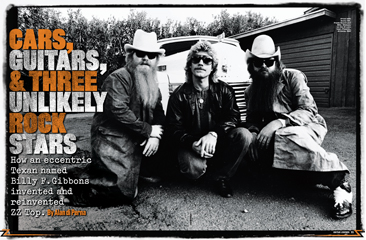

ZZ Top: Cars, Guitars, & Three Unlikely Rock Stars

How an eccentric Texan named Billy F. Gibbons invented and reinvented ZZ Top.

ZZ Top guitarist and mastermind Billy Gibbons is a compulsive shopper. Late one recent Hollywood night he could be found prowling the aisles of the Virgin Megastore on Sunset Boulevard, moving stealthily like some African tribal huntsman, albeit one with a long grey beard, strange tufted hat, natty black suit, ample silver wrist jewelry and a white shirt accentuating the night-owl pallor of that small portion of his face left visible by his legendary chin warmer and bizarre headgear. The Great White Hunter! He swoops down the aisles, deftly picks through stacks of CDs and extracts the discs that capture his fancy: a collection of cuts by Fifties steel guitar legend Speedy West, some Los Lobos albums to prepare for a jam with the famed L.A. band at the Latin Grammys, and a worldbeat compilation for the missus, the comely actress Gilligan, who is approximately half Billy’s age. “She goes crazy for this stuff,” he confides.

For me he selects a CD by country star Brad Paisley, a new friend of Billy’s, whom he rates pretty highly as a guitarist. Next, Mr. Gibbons roots through the bargain bin, commenting authoritatively on tacky but obscure disco tracks that maybe he ought not admit to knowing so well. Then it’s on to the DVD racks. Billy’s craving some film noir tonight, that ominous, black-and-white, B-movie genre, filled with razor-sharp killers, dangerous gun molls and other desperate characters from the fringes of mid–20th century American society. Billy digs and digs, growing visibly frustrated. He can’t find one he hasn’t already seen, but he does present me with a copy of Dillinger, quite possibly the only film noir I’ve never seen.

Billy’s knowledge of film is as encyclopedic as his command of musical idioms both high and low. Just name a cinematic genre: vintage Hollywood, Italian neo-realism, Sixties kitsch, Asian slasher flicks… Billy can name directors, cinematographers, minor actors and actresses. He possesses a highly retentive and wildly associative mind that seems to require constant stimulation. One song or movie title will trigger an avalanche of related titles in his fevered brain. He scurries off to track them down.

The uniquely configured, hyperactive mind of Billy F. Gibbons is the engine that drives ZZ Top, that Little Ol’ Blues Band from Texas, now in its 38th year of operation and likely to keep on running infinitely, thanks to the caffeinated Energizer bunny that resides in the curiously adorned noggin of Billy F. Gibbons.

“Billy’s an interesting guy,” says Dusty Hill, ZZ Top’s bassist and Gibbons’ bandmate for the past four decades. “He’s got a lot of varied interests. If you’re involved in some venture he’s into, you really get into it.”

Everybody knows that ZZ Top are one of the greatest things ever to spring from the Texas mud, but fewer people get the Hollywood connection. Billy’s dad, Fred, was a soundtrack musician and composer for MGM during the Thirties. His uncle Cedric is one of the most celebrated cinematic art directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. In fact, Billy inherited the family manse in the Hollywood Hills. The adobe-style dwelling is brimming with further artifacts of Billy’s mania for shopping. Museum-quality pieces from his world-class collection of African art adorn the rooms. A number of vintage automobiles, all of them black, are parked out front. And, of course, there are guitars and amps everywhere—rare ones, new ones, the weird and the wonderful: a Billy Bo Gretsch Jupiter based on an ax given to Billy by rock and roll legend Bo Diddley, a brand-new black JB Tele adorned with sparkling jewels, a few pawnshop specials, three Watkins Dominator amps of different vintages and a Marshall Bluesbreaker in red-orange Tolex.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There’s even more stuff at Billy’s house in Houston, the city in which he was born. Houston is also the site of ZZ Top’s recording studio, Foam Box, and eight warehouses containing the bulk of Billy’s African art collection, hundreds of guitars, amps, effects and Lord knows what else. Billy divides his time between the L.A. and Houston residences as well as various other locales. No one fully understands the comings and goings of Billy F. Gibbons. That’s one of the rules.

The Houston Billy is the one everybody knows: the deep-talkin’ Texan with a passion for barbecue, roadhouses, mud-flap gals and stockcar racetracks. But Billy’s Hollywood flair is every bit as crucial to ZZ Top’s identity and longevity as the group’s deep Texas blues roots. His penchant for showmanship and sharp eye for visuals (a genetic legacy from Uncle Cedric, perhaps) has enabled him to reinvent the band for each succeeding era.

Any one human being’s conception of ZZ Top depends heavily on the decade in which that particular human being made the passage through adolescence into adulthood. For those who came up in the Seventies, ZZ Top are the ultimate beer-drinkin’, hell-raisin’, good-timin’, ass-kickin’ party band. This is the ZZ Top of “Tush,” “La Grange,” “Whiskey’n Mama” and “Enjoy and Get It On.” For Eighties fans, they’re one of the most ubiquitous, albeit unlikely, icons of the MTV era, three sharp-dressed men with a sound as gleaming and streamlined as the custom hot rods and curvaceous cuties seen in the video clips for “Gimmie All Your Lovin’,” “Legs” and “Sharp Dressed Man.”

In the Nineties and beyond, ZZ Top returned to their roots and emerged as curious curators of the blues legacy. Bearded barrelhouse gurus, semi-mythical characters, they came to remind us that rock and roll ain’t nothin’ but the bastard offspring of the blues and hillbilly music. This is the group that brought us “My Head’s in Mississippi,” “Fuzzbox Voodoo,” “Poke Chop Sandwich” and “Buck Nekkid.” Bless their grizzled beards.

One common denominator in the whole grand pageant of ZZ Top reincarnations is that rich tone and distinctive guitar style of Billy F. Gibbons. Every note is steeped in the rich American musical heritage that Billy absorbed growing up in Houston in the Fifties. Some of his earliest musical memories are of the diverse sounds coming out of the radio, what we now call “roots music.”

“The favorite channels on the dial,” Billy recalls, “seemed to be the R&B stations KYOK and KCOH that played all the blues you could use and also country-and-western tracks of the day, back when Hank Williams reigned king. In those radio offerings, one could hear the crossover elements that led to the birth of rock and roll: the blues meeting country, meeting hillbilly and even bluegrass—all of this wild, ‘nonlegitimate’ music, a heartfelt, more soulful kind of invention. Radios were still in a rather primitive vacuum tube state back then, so you could turn them up loud and get beautiful rich distortion.”

Billy’s dad had moved on from Hollywood’s studio orchestras to become a conductor of the Houston Symphony Orchestra and high-society bandleader. But Billy’s musical education continued on an entirely different track at age seven, when a reckless babysitter began to bring young master William and his five-year-old sister out to the local Houston nightspots, where the future leader of ZZ Top got his first taste of live blues and R&B music, played in the smoky dives that are the proper environment of these musical idioms. The next major turning point occurred on Christmas morning of 1962.

“I got my first guitar on Christmas day, shortly after I’d turned 13,” Billy says. “It was a single-pickup, single-cutaway Gibson Melody Maker, with a Fender Champ amp. I immediately retired to my room and learned how to play the intro figure from Ray Charles’ ‘What’d I Say,’ and by sundown I had started learning the signature Jimmy Reed rhythm lines.”

HANGIN’ WITH HENDRIX: LIFE BEFORE ZZ TOP

Billy played in a variety of junior high and high school rock bands during that golden mid-Sixties era when groups were forming in garages and basements across America, knocking together their own rough take on the British Invasion sounds of groups like the Rolling Stones, Kinks and Yardbirds. But his first fully professional act was the Moving Sidewalks, a psychedelic blues outfit patterned after Texas’ celebrated 13th Floor Elevators. The late Sixties had arrived. Hippiedom was taking hold.

“There was this big house in Houston called the Louisiana house,” Billy recalls. “It was this giant, beautiful 1920s mansion, and it became the big hippie house in town. There were little cubicles that became rooms to live in. The Elevators lived there. We moved in. The Red Crayola, another remarkable psychedelic band, lived there too. Those guys were artists of all sorts. Visual artists. The house was a real interesting kind of artistic enclave. It was not restricted to just musicians; there were light-show guys, all kinds of people.”

Billy himself had considered a career in the visual arts shortly after high school. “I had enrolled in art college and then went up to Austin to go to the University of Texas to study art,” he says. “But the music was a stronger call at that time. It was either one or the other, and I chose music, although I kept on with my art fixation, this never-ending quest to figure out how to draw a line from point A to point B.”

But the art school refugee soon found ways to manifest his bizarre visual sensibilities through music gear. Billy’s mania for the wild customizing of guitars dates back to his Moving Sidewalks days. Evidence of this can be found in his recent coffee table book, Rock and Roll Gearhead. On page 152, we find a photo of a strange, square-bodied custom job lined with pink fur, the forebear of the well-known fuzzy guitars from ZZ Top’s MTV era two decades later.

“I was always a big fan of Bo Diddley,” says Billy. “And if you look closely at the cover photograph on the LP entitled Bo Diddley Is a Lover, as he sits on the floor, he’s got his famous rectangular Gretsch on one side and on the other side there’s a single-cutaway Gibson Les Paul Jr. that was covered in shag grey carpeting. This was truly the inspiration to emulate that kind of crazy guitar craft, which I did on a butchered Telecaster, aided and assisted by D.F. Summers, the bass player for the Moving Sidewalks. He was also quite talented as a craftsman in guitar building—only in those days, it wasn’t so much guitar building as guitar aberration. We learned how to ruin quite a few guitars real quick.

“But Mr. Summers helped bring those early custom guitar ideas into reality, even going on to create the first spinning guitar. He devised a spinning device that he added to his Flying V bass during the Moving Sidewalks’ tour with Jimi Hendrix. There were a couple of moments in the set where we turned D.F. loose. Of course, he had to unplug his bass to avoid getting the patch cord tangled up when the instrument was spinning. [This was years before wireless, of course.] But it was such a magnetic visual thing. D.F. Summers loaned his talents years later to the ZZ Top spinning furry guitars. So what goes around comes around.”

“It was unspoken but quite evident that Hendrix threw caution to the winds,” Billy notes, “and decided to do things to and with a guitar that were not necessarily written in any of the how-to books. For instance, it was considered a no-no to chain two Fuzz-Tones together. But I saw Hendrix chain five of them together! And he’d do this personalized dance, stomping on five different pedals, sometimes playing with all five of them on at once. I think it’s fair to give him the award for breaking the rules and starting to do things that no one dared do before. That was part of his genius: a total lack of fear.”

ENTER PEARLY GATES: THE BIRTH OF ZZ TOP

By the start of 1969, the reverb-drenched, combo-organ enhanced, early psychedelic sound of the Moving Sidewalks had been all but totally eclipsed by the heavier power-trio vibe initiated by groups like the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Cream and Blue Cheer. Around this time, which coincided with the United States’ escalation of the Vietnam War, the Sidewalks’ bassist and organist were drafted into the army. This left Billy free to pursue his dream of forming his own power trio.

And so ZZ Top were born. The original incarnation featured Billy, Moving Sidewalks’ drummer Dan Mitchell and Lanier Greg on bass. This lineup recorded one single, “Salt Lick,” backed with “Miller’s Farm.” It was okay, but things didn’t really gel until the drummer Frank Beard and bassist Dusty Hill fell into place as the ZZ Top rhythm section that would reign supreme for the next four decades.

Hill and Beard had played together in their own psychedelic blues outfit, American Blues, which released two albums: American Blues Do Their Thing and American Blues Is Here. “There were song titles like ‘Chocolate Ego’,” Hill says, laughing. “You get the idea. Also, I’d played with Freddie King on and off. I played at the Fillmore in San Francisco for two weeks with Freddie. Ike and Tina Turner were on the bill, along with Buddy Guy, Blue Cheer and Electric Flag [a Sixties act that featured guitarist Mike Bloomfield and future Hendrix collaborator Buddy Miles.]”

Clearly, Dusty and Frank were a seasoned rhythm section by the time they joined forces with Gibbons. “Billy’s band opened for Hendrix,” says Dusty. “American Blues opened for the Animals and Herman’s Hermits. In fact, we had a little party with Herman’s Hermits after the show. You can imagine. It didn’t go on all night long. Well, at least nobody hit anybody. I think it broke up just in time.”

“I don’t think they were the partiers that we were,” Beard adds.

Beard joined ZZ Top first and then brought Hill into the picture. Dusty beat out a bunch of other potential bassists. His audition quickly morphed from a try-out to a joyous, hour-long jam on a blues shuffle. It’s one of the legendary episodes in ZZ Top lore.

“Dusty and I knew each other’s tricks,” Beard explains. “So automatically his audition sounded four times better than the other bass players we were auditioning. I really wanted Dusty in the band. So when the other bass players were up there, I made sure it was plenty lame. When Dusty got up there, we knew all these little punches and kicks we could do together at certain points. And it was like, ‘Wow! Oh man!’ ”

Nearly as important as finding the right rhythm section—even more some might say—was finding the right guitar rig to bring that raw, raunchy ZZ Top sound to life. In the Moving Sidewalks, Billy had used mainly Strats and Teles through American-made Vox Super Beatle amps. Now he was after a heavier sound and had decided he just had to have a Les Paul and a Marshall. In 1969, mind you, this was far from being the standard gear configuration it is today. Marshall amps were brand new in the States, and guitarists were just beginning to recognize the value of the Les Paul as a weapon of rock destruction.

“The mystique of the sunburst Les Paul,” Billy explains, “was first ignited by Keith Richards, who had what is thought to be the first sunburst that made the London scene. You’ve probably seen pictures of Keith Richards’ ’burst with a Bigsby. What makes that instrument intriguing is that you also see photographs of it being played by Jimmy Page, Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Jeff Beck. So it must have been passed around a bit. But what really got me excited about the sunburst Les Paul was the back cover of the first John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers LP [released in 1965], the ‘Beano’ album [Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton]. There we see Eric Clapton with a Les Paul and a Marshall combo amp in the background. And immediately those who could put two and two together began to suspect that this wonderful guitar sound and its richness of tone might be the result of that combination of guitar and amplifier. So the quest was to go find a Les Paul sunburst and a Marshall amplifier.”

Billy got the guitar first: a 1959 sunburst Gibson Les Paul that has passed into legend under the name Pearly Gates. There are many myths as to where Billy obtained Pearly, the most prominent being that the guitar was found under a bed. Billy will admit to paying $250 for the guitar, an incredible deal when you consider not only what the instrument is worth today but also the staggering amount of good use Billy has gotten out of Pearly on every ZZ Top album from the very first to the most recent.

“Out of the 1,750 or so sunburst Les Pauls made between 1958 and ’60, although each has its own stylized personality characteristics, I’ve yet to find one that is not rip-roarin’ groovy,” Billy declares. “They’re all wicked. But Pearly remains the queen. I guess she was just made on the right day, with the right piece of wood, right amount of paint, right amount of wrapping on the pickup. I can always rely on Pearly to make the amp stand up and bark. Pearly is such a powerhouse, high-output instrument. It will kick the preamp’s butt. And when the preamp barks, the amp will follow.”

With his coveted sunburst Les Paul in hand, Billy set about acquiring the amp of his dreams. The magic wizard who made this wish come true was none other than Jeff Beck. Or more accurately, Jeff Beck’s roadie.

Fellow hot-rod enthusiasts and guitar aces both, Gibbons and El Becko bonded on one of Beck’s very first U.S. tours.

“Jeff stopped at Houston for a show, and I had the opportunity to hang out with him a little,” Billy recalls. “And I was fascinated by these giant, tall amplifiers he had, these Marshall 100-watt rigs. It was the Super Lead 100, model number 1968. And it was Jeff’s roadie who had a friendship with Jim Marshall and had a way to buy Marshalls cheap and get ’em into the States. Interestingly enough, we used the same Marshall rig for Dusty’s bass playing. The wealth of grind that those amps offered worked just as well for bass as for guitar. So we had two identical amp stacks, both being guitar rigs, that we used for guitar and bass. They were purchased for $800 U.S., delivered. And they didn’t require transformer voltage power supplies. They were some of the first ‘made for U.S.’ 110-volt Marshalls. We bought two and very quickly reordered two more. One is good, more is better.

“Those amps played a big role in how to solve the trio puzzle: how to make three sound bigger than, or more than, three. Those distorted tones interacted to fill the holes. The once skinny sound of three instrumentalists suddenly became real wide, no holds barred and all holes filled. It was great for us, because we didn’t have to hire sidemen; we kept the band three. It was a lot more affordable. Fewer arguments, too.”

THE LONDON YEARS, PHASE ONE (1970–72): MICK DIGS ’EM!

By now, ZZ Top were starting to attract attention. Their manager, Bill Ham, secured them a deal with London Records. The guys were delighted to be on the same record label as the Rolling Stones. They promptly holed up in a small Texas recording facility, Robin Hood Brian Studios, and knocked out their debut disc, aptly named ZZ Top’s First Album and released in 1970.

“We attempted to create material written by the three of us, with no idea of where it would go,” Billy says. “What you hear is what you get. The tone of that record is appealing in that we were merely upstart copyists attempting to present our version of the blues, coupled with what we thought would sound like Keith, Beck, Page, Clapton, Mick Taylor, Peter Green…those guys. Growing up, Frank and Dusty had listened to the same radio stations I did: the late-night station out of Nashville, WLAC, and the same Mexican border blasters. So we had a shared experience from the start that was able to be brought forward in the creation of ZZ Top, plus the bonus of having newfound heroes in the British Invasion guys. It was a handy way to start.”

The album is very much a “live in the studio” affair, recorded with the group’s newly acquired touring rig. “The first album is all Pearly Gates through a 100-watt Marshall,” Billy explains. “Dusty was playing a Danelectro Longhorn bass through his 100-watt Marshall. In famous Dusty fashion, he forgot to bring his ’51 Tele bass to the studio, so he had to use the house bass at the studio, which was this weird Danelectro Longhorn. I think it was a two-pickup model, or maybe a single. And that’s what made up the sound.”

Shortly after the debut album was completed, Billy took his first steps toward amassing the impressive guitar collection that he possesses today. “Pearly had such a robust and distinctive personality, and it was my goal to get a spare,” he says. “Looking at Pearly, I thought, Let’s see, this is just a chunk of wood. It must be these humbucking pickups that make it sound so great. So my goal was not, ‘Let’s get another sunburst Les Paul!’ it was, ‘Let’s get another Gibson guitar with these humbucking pickups!’ We didn’t even know that the sought-after humbucking pickups were the ones marked ‘PAF’—Patent Applied For, the first early humbuckers.

“But my second two-humbucking Gibson was a 1958 korina Flying V. A buddy down the street said, ‘Hey man, you wanted a Gibson with two humbuckers. I got one I don’t need. I’m still playing my Fender. So do you want to buy this Gibson? I don’t even know what it is. It’s kind of odd. It’s hard to hold on your leg and play. But it’s got the pickups you want.’ I said, ‘Well, if it’s got the pickups, bring it over. How much you want?” And he said, ‘Three hundred bucks.’ That was $50 more than I paid for Pearly, but I said, ‘Okay, fine.’ And yes, it had a great sound. It was a far cry from the shape of the Les Paul, but it had those early PAFs.”

Billy’s guitar collection had grown appreciably by the time sessions for the second ZZ Top album, Rio Grande Mud (1972), rolled around. “I had acquired some more of those two-humbucker Gibson guitars,” he says, “none of which were matching up to Pearly. They were a little less loud, so I remained on the quest. I said, ‘Certainly there’s another guitar out there that sounds like Pearly.’ But I’ve yet to find one. Close, yes. But Pearly is still the benchmark.”

Nonetheless, several of those other guitars came in handy for overdubs on Rio Grande Mud. Billy made extensive use of a 1956 sunburst Fender Stratocaster, which provided a nice single-coil counterpoint to Pearly’s throaty roar. “Moving from the first album to the second,” Billy notes, “we thought, It’s not out of our realm to use a few different guitars and amps to get some different sounds. The music explosion that was taking place at the time was providing a wide range of tonal variances, and that’s when we were willing to get inventive.”

Slide guitar overdubs made their first appearance on Rio Grande Mud. Billy used a 1958 Sunburst Les Paul—not quite Pearly but not at all shabby—for the slide leads on “Just Got Paid.” He plays slide in a variety of open tunings. “ ‘Apologies to Pearly,’ also from Rio Grande Mud, is an instrumental slide number played in open E,” he explains. Open G [D G D G B D] and open A [E A E A Cs E] are two more favorites.

ZZ Top’s initial “Southern Man” persona started to come into focus on Rio Grande Mud. Songs like “Just Got Paid” and “Chevrolet” project a strong, blue-collar, workin’-man identity. But their fondness for cowboy hats and western garb was known to cause confusion back in 1972. For instance, the crowd was a mite perplexed when ZZ Top opened for the Rolling Stones in 1972.

“We got word that Mick Jagger heard our first album and liked it,” Dusty Hill relates. “And he wanted us to open for the Stones in Hawaii. That just blew us away. But the next thing I heard was that Stevie Wonder opened for them here in the States and actually got booed at one show. So I was scared to death. We get onstage in Hawaii with our cowboy hats, boots and jeans and you could hear a pin drop. Somebody went, ‘Oh no, they’re a country band.’ ”

“But we had our Marshall stacks cranked and we were ready to pounce for the kill,” says Billy, taking up the tale. “We very quickly had to get grinding to dispel the myth: Yeah we may look like we just fell off a wagon, but we’re here to entertain.”

“We got an encore on all three shows we did,” Dusty adds. “And it was written up in Rolling Stone or something like that. It was one of the first big steps for us. And I’ve got great memories of that, like meeting Charlie Watts down at the bar and having a few.”

THE LONDON YEARS, PHASE TWO (1973–76): SHITKICKERS ON ACID

The album that put ZZ Top on the map was Tres Hombres. Released in 1973, it was the record that crystallized ZZ Top’s sound and early style.

Like Rio Grande Mud, the title Tres Hombres reflects the influence of la Frontera, the Mexican border flavor that creeps into Texan culture in general and the ZZ Top aesthetic in particular. And by this point, ZZ Top had become a highly seasoned live act, an inevitable byproduct of almost constant touring.

“Not to knock London Records, but they didn’t do a great deal for us,” says Hill. “We were humping every night. Any gig. Every gig. Opening for whoever we could.”

At the same time, with two albums under their ornate western belt buckles, ZZ Top had become comfortable and highly competent in the recording studio. All of these factors helped to make Tres Hombres the group’s first Platinum album and an enduring catalog item to this day.

“Tres Hombres was our first breakthrough, and it’s still a favorite disc with fans and the band,” says Billy. “One of the reasons for that is that it has our first Top-10 hit, ‘La Grange.’ ”

ZZ Top’s tribute to a legendary Texas brothel, “La Grange” is a shuffle boogie in a style initiated by bluesman John Lee Hooker and revived by late- Sixties blues group Canned Heat. ZZ Top put their own stamp on the idiom, although Billy’s low-pitched lead vocal came about somewhat by accident.

“We’d cut the music track, and I was working on the vocal,” Billy recalls. “But somehow it was not gelling. We worked and worked on it. I remember the session had started early, and we’d gotten to the point where everyone was getting fatigued and hungry. So I said, ‘Look, take a lunch break.’ And I remember, I was sitting in a metal folding chair, having stood up in front of the vocal mic for hours. I pulled the microphone down and asked the engineer to give it one more try. But he was having some kind of technical difficulty and said, ‘Uh, you’ll have to wait a minute until I figure this out.’

“After a little while he said, ‘We’re running, but I’m not sure if we’re taking [i.e. recording] this. You’ll probably hear it in your headphones, but don’t pay any attention to it.’ So I heard the music start. And it was just one of those things where I started horsing around with this low voice. I got through the first stanza of the two. I happened to glance up through the control room glass and the engineer was looking happy and excited, making gestures that seemed to say, Keep going. You’ve got something here and we’re getting it on tape! And that was the take and the final keeper—the vocal you hear on the record.”

The extra beefy guitar track combines two of Billy’s favorite guitars: Pearly Gates and a 1955 maple-neck, hard-tail Stratocaster, both pumped through 100-watt Marshalls. The combination of Pearly’s Les Paul/humbucker low-end growl and the Strat’s crisply defined, singlecoil sparkle is a potent one. The Strat is heard first, stating the song’s main chordal theme. Then the Les Paul comes in when the drums and bass enter, doubling the Strat’s rhythm pattern and kicking the groove into overdrive.

“That ’55 Strat is just one of those great-playing, great-sounding instruments,” Billy says. “I still have it. By the time we recorded Tres Hombres, we’d entered the era of the overdub. So it gave us a glorious opportunity to bring both Pearly and the Strat into the picture.”

Billy also used the Strat to play both of the song’s memorable solos. The second lead is the first ever on a ZZ Top disc to incorporate pinch harmonics, a technique that would become a signature element of Billy’s guitar style. “And that happened quite by accident, too,” he notes. “I had not studied it or anything. I just really came across it and said, ‘Gee, this is an odd effect.’ At that time it was quite novel. Those harmonics can be highly unpredictable. But the technique is basically pick followed by flesh from the thumb. My question is how does Dusty do it without a pick? How does Dusty play at all is my question. But he plays very well. He’s the best, and very loud.”

Like ZZ Top’s First Album and Rio Grande Mud before it, Tres Hombres was recorded at Robin Hood Brian Studio in Texas, but it is the first ZZ Top album to be mixed at Memphis’ legendary Ardent recording studio, one more factor that puts it in a different league than its predecessors. Memphis, Tennessee, is one of America’s great music cities, known, with some justice, as the Home of the Blues. B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Otis Redding came from Memphis. With Sun Studios, Sam Phillips’ Memphis Recording Service and Stax and Ardent in town, Memphis has always been a great recording destination as well. ZZ Top first came to Memphis to play a blues festival. The promoter had heard their records and assumed they were black. This misunderstanding made them the only white artists on the bill, but everything worked out fine in the end.

“There were a lot of local musicians hanging about,” Billy narrates. We made such a good impression that we had the opportunity to meet them after the show was over. All the local hotshot gunslingers were there. And a couple of them said, ‘Gee whiz, you guys make some pretty good records. Why don’t you consider recording here in Memphis?’ I said, ‘We’ve just completed a series of recordings which we’re ready to take to the next level. We call it Tres Hombres, in keeping with our Tex-Mex origins.’ They said, ‘Since you already recorded it, would you consider mixing it here? We have a studio here in Memphis called Ardent, and there’s some real handy talent on the engineering staff. As a matter of fact, Led Zeppelin have just finished recording their Led Zeppelin III album at Ardent.’

“Well, that was big news. After a brief discussion, we decided, Let’s give it a try. And having mixed our first Top-10 record at Ardent, which was a big deal, we now had a bond with music made in Memphis. And we worked at Ardent recording studio for the next 20 years.”

It was a no-brainer for the band to head for Ardent when the time arrived to record the follow-up to Tres Hombres. The studio sessions would yield half of what became ZZ Top’s second Platinum success, Fandango. The other half of the album was culled from a hell-raisin’ live show in New Orleans. So fans got the best of both worlds: some first-rate ZZ Top studio tracks and a taste of the live sound that had made the group a hot concert draw in the Seventies. The album also offered the wider palette of guitar tones than any of its predecessors.

“Fandango was when we were starting to show up bringing truckloads of guitars,” Billy says. “This was a real turning point in learning how to experiment with unusual gear. It turns out that the engineers who worked at Ardent—John Hampton, Terry Manning and Joe Hardy—were all gearheads and had rooms of off-the-wall equipment they had managed to amass. One of the favorite amps on that album was a Silvertone 2x12 combo that had belonged to Alex Chilton [Memphis legend of Box Tops/Big Star fame who frequently recorded at Ardent]. Many of the artists who passed through Ardent ended up using it. And there was a 4x12 tweed Fender Bassman and a little top-loading tweed Fender Harvard with a 10-inch speaker that had belonged to Steve Cropper [Memphis guitar legend of Stax Records/Otis Redding/Booker T. and the MGs fame].”

Billy’s distorted tones on Fandango tracks like “Nasty Dogs and Funky Kings” hit a new level of graininess—a tough, squared-off, highly clipped tone that would become another signature Gibbons guitar timbre. Billy attributes the tonality in part to the advent of solid-state compressors, mic pre-amps and other studio gear coming into currency at studios like Ardent in the mid-Seventies. Elsewhere on the disc, “Heard It on the X” is a superb slide workout in open G, and “Blue Jean Blues” features some of the most lyrical, minor-key, slow-blues playing Billy has ever done. For the song, he played a maple-necked ’59 Strat, and the resulting clean tone shimmers with amazing depth and clarity.

“That was another studio experiment,” says Billy. “The guitar was plugged directly into the board. Our equipment truck had broken down and we had no amps, but the clock was running and the engineer said, ‘Well, if you just want to get something down on tape, we can plug your guitar straight into the board.’ Of course, Fenders are by nature ultra-clean and bright, so putting that Strat through the board worked for that particular tune. ‘Blue Jean Blues’ could be called one of the more haunting slow-blues-based numbers that we’ve managed to get down. The quietness of it all allowed that clean effect to be used to good advantage. It’s very different from what we’re known for—a kind of rash, hard, distorted tone. But it’s still a favorite.”

By far the best known track on Fandango, however, is “Tush,” a brash uptempo shuffle that became a major hit for ZZ Top. There are numerous, varied and highly imaginative interpretations of what the word “tush,” as applied in the song, actually means, but it’s clearly the tale of one man’s quest for something fine, sung with fearsome upper-register intensity by Dusty Hill.

“We wrote ‘Tush’ at a soundcheck in Alabama in about six or eight minutes,” the bassist recalls. “It was hot as hell, and with the exception of a very few words the song you hear on the record is what we wrote that day. We always tape our soundchecks for that very reason [i.e. songwriting]. Usually, though, it’s a little lick or a vocal line or something, not a whole damn song!”

The only thing that could match the intensity of “Tush” is a full-on live set by ZZ Top, which is exactly what five of Fandango’s songs deliver.

“For that particular show, we were at a famous New Orleans venue called the Warehouse,” Billy recollects. “It’s a great room, a turn of the century, wood-and-brick warehouse right on Tchoupitoulas Street in a line of many old warehouses. Not only was it a popular place to go but the sound inside was fabulous. With that much brick and old wood, it was just this resonant box of tone. It didn’t really matter what you brought into there, the room made it sound great. Everybody I’ve ever talked to who played at the Warehouse has said, ‘Yeah, isn’t that a great-sounding place to play?’ ”

The Platinum success of Tres Hombres and Fandango enabled ZZ Top to mount one of the most ambitious and bizarre tours in all of rock history. ZZ Top’s World Wide Texas Tour was billed as “Taking Texas to the People.” They meant that literally. The 35,000-square-foot stage was hewn in the shape of Texas and weighed 35 tons. It took five massive trucks to transport this mammoth stage and all its attendant rigging, not to mention ranch-hand props that included fences, windmills, live cacti and livestock. Yes, a live steer and buffalo, along with assorted breeds of buzzard and rattlesnake, all had roles in the big extravaganza. They were attended by fully qualified animal handlers, who also traveled with this rolling rock and roll circus. Nonetheless, sometimes the critters got loose, terrorizing concertgoers.

As for Gibbons, Hill and Beard, they were decked out in elaborately stitched and ornately studded western suits designed and handmade by the famous country-and-western tailor Nudie Cohn. The outfits included big ol’ cowboy hats, naturally. Billy and Dusty played custom axes with Texas-shaped bodies. By this time, Billy’s lifelong quest for a guitar equal to Pearly had led him deep into designing custom instruments. Gibson made him the Texas-shaped guitars, but over the years, Billy has hatched increasingly outrageous guitar designs with a number of top luthiers, John Bolan being a particularly favorite accomplice.

By way of context, the Worldwide Texas Tour rolled down the highway at a time when musical stars like David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Kiss and Parliament-Funkadelic were mounting highly elaborate concert tours, bringing larger-than-life guillotine executions, spaceship landings and other spectacles to the rock stages. Seen against the backdrop of these big shows, the World Wide Texas Tour functioned as both competition and parody.

The mid Seventies were also a time when glam was very much the prominent fashion mode in rock. A lot of groups and their fans were trying to look like androgynous, decadent, urban, ultrahip space aliens. Meanwhile, ZZ Top were going around like shit kickers on acid—very much the antithesis of glam, although every bit as dressed up and image conscious as the glamsters. The cowboy hats that had been a liability in ’72 had been transformed into a high-concept statement, a kind of redneck drag. This wry over-insistence on their Texas roots was one of several factors that separated ZZ Top from the herd of “southern boogie” bands that had also gained currency in the mid to late Seventies.

And like all great concepts, it functioned on several levels. More down-home fans could raise a longhorn Bud in the air and holler “hell yeah!” while hipsters could feel like they were sharing an inside joke. ZZ Top were following the age old showbiz maxim: Take whatever it is you’ve got and exaggerate it.

“Well, we had a glaring awareness of our inability to look like fashion models,” Billy deadpans. “To this day, one of the band in-jokes is aimed at our fearless bass player, Dusty Hill, who is known for being immune to fashion. Be it clothing, the favorite guitar of the day, the newest amp, you will not find it in Dusty’s closet. In the beginning, we didn’t have time to design wardrobe; we were touring too hard, busting our ass to get to the next show and going onstage in whatever we happened to be wearing. That in itself became part of the perception of ZZ Top: ‘Oh yeah, they’re those Texas guys, I’ve seen them. They wear cowboy hats and cowboy boots a lot.’ What started out as every day clothing to leave the house in over the years became a trademark, whether intentional or not.”

Keeping the Longhorn State motif going, ZZ Top decided to name their next album Tejas, the Spanish spelling for the territory that had once been part of Mexico. It’s another classic, bluesy ZZ Top disc, but a pronounced country influence also creeps into the mix. The album’s hit single, “It’s Only Love,” is not only one of catchiest things the band has every done but also possesses an unmistakable twang. And “She’s a Heartbreaker” is as country as it gets.

“Oh, without question,” Billy concedes. “Around that time I was driving from Houston down to Austin a lot of hear the Fabulous Thunderbirds, who were just getting started and playing ‘Blue Monday’ nights at a pizza joint in Austin called the Rome Inn. And halfway down, you could start to pick up this great Austin radio station, KOKE-FM. One of the DJs on there decided to turn the playlist upside down and create a format that could go from George Jones to the Rolling Stones, back to back. That certainly had an impact on me.

“And at the time, there was this great wave, a new movement coming out of California: country rock. It had started when Roger McGuinn allowed the Byrds to go in that direction on Sweetheart of the Rodeo: the cowboy-ification of rock, with pedal steel guitar showing up on rock records. And coming out of that lineup of the Byrds you had Graham Parsons and his band, the Flying Burrito Brothers. And Graham was of course hanging with the Stones in the era when they were doing things like “Wild Horses,” “Dead Flowers” and “Country Honk.” Along with that there was Poco, the Eagles…just a real fun, ‘let’s be cowboys for a day’ kind of thing.

“So not wanting to be left behind, we took measures to see if we could stay in step with the trend. Some fans were surprised. But some of them remembered that our second single, ‘Shakin’ Your Tree,’ had pedal steel on it. And one of my all time favorite country-tinged ZZ Top numbers is ‘Mexican Blackbird’ from Fandango, which is definitely a slidester’s chewed-up version of rock-meets- country, inspired by that particular period.”

But what’s interesting is that there’s a bit of Keef in Billy’s country playing. The chordal voicings and edgy clean tones on both “It’s Only Love” and “She’s a Heartbreaker” owe a lot to Keith Richards’ London take on the country idiom.

“Oh, without a doubt,” Billy admits. “The Stones have been a benchmark for so many aspiring rock musicians. They’re true-blue interpreters of American music. They took up the blues and R&B at a time when it was by and large being dismissed at home. And they explored country music in the same way. They were pals with some of those California bands. And, yes, I would spend hours upon hours studying Keith’s playing style and his chord voicings. It took me a long time to realize he played a five-string Telecaster in open G. Boy, that was a brand-new day when I figured that one out!”

THE LONG HIATUS: ZZ TOP EXPLORE THE GLOBE

Shortly after the release of Tejas, ZZ Top decided it was time for a break. They’d been touring hard and heavy since 1970, and the logistical rigors of the Worldwide Texas Tour would’ve been enough to kill lesser men. “It started out that we were going to take a 90-day hiatus from public appearances,” Billy says. “That allowed us to enjoy a little getaway. Frank went to Jamaica, Dusty went to Mexico, and I was off to Europe. Well, three months became six months, which became a year, which became two years. We were still in touch, but it was kind of a long-distance love affair.”

Asked what brought him to Europe, Billy promptly answers, “The first Fripp and Eno album, No Pussyfooting.” Gibbons had become intrigued with the European art rock movement of the Seventies. Former King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp and Roxy Music vet Brian Eno had become part of a scene that also included players like Pink Floyd associate Robert Wyatt and guitarists Fred Frith and Kevin Ayers, playing in bands like the Art Bears and Henry Cow. It was all a mighty long way from Texas, but it did involve making noises with guitars. So Billy was down.

“Granted, during the Moving Sidewalks days, we got to know Robert Wyatt from the Soft Machine,” Billy says. “Talk about headtrip, way-out-there art rock. And in the Seventies there was a lot of that scene going on in England. And if you check out the liner notes to some of those early Fripp and Eno releases, they go to great lengths to reveal their studio system: ‘You have to go through an echo unit here, then run the signal through this…’ It becomes quite fascinating, not only as an insight to what they’re doing; it also stimulates one’s own curiosity: Wow, if they can do that, I wonder if I can do this. But some of the really obtuse art rock was coming out of Paris, France. So I spent some time there, too.”

Billy also got interested in reggae music. The Jamaican musical idiom was at a high point in the Seventies and very much a part of the decade’s “alternative” musical Zeitgeist. Billy got to know both Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, spending some time in Trinidad with Marley.

“Bob was an intense kind of guy,” Billy says of the reggae icon: “very set on doing things his way. He was a great leader for that outfit [the Wailers]. He had an incredible rhythm section behind him: [drummer] Carly and [bassist] Aston Barrett. Carly Barrett’s treatment of the beat was so unique. There isn’t a two or a four in early reggae. There was a name given to that beat: “the one drop.” The reggae sound coming out of Jamaica in that glorious period from 1971–77 is to this day considered the real essence of when reggae ruled.”

THE WARNER YEARS, PHASE ONE (1979–81): NEW STYLES IN MUSIC AND FACIAL HAIR

So when ZZ Top finally reconvened in 1979, Billy’s musical perspective had been stretched in several new directions. Frank had picked up some Jamaican influence as well. It was the start of a new era for the group in many ways. They had also left London Records and signed a deal with Warner Bros.

All these paradigm shifts are reflected on the band’s first album for their new label, Deguello (1979). There is a greater emphasis on clean chorusy guitar tones than ever before, and an arch sense of postmodern irony in songs like “Cheap Sunglasses” and “Fool for Your Stockings.” It all very much reflects the impact of new wave, the postpunk musical style that rubbed shoulders with art rock in the late Seventies. (Eno had gone on to produce Devo and the Talking Heads; Fripp had formed the League of Gentlemen with a trio of new wave musicians.) In true DIY punk/new wave fashion, the members of ZZ Top even taught themselves to play saxophone in order to add some horn charts to the disc.

“One of the highest compliments at the time,” Billy recalls, “came from the late rock critic Lester Bangs, who said that ‘Cheap Sunglasses’ was chosen as a favorite by someone wearing purple hair who did not realize who they were listening to. Thank you Lester, thank you purple hair, thank you cheap sunglasses, thank you Ray Charles.”

The cowboy hats all but disappeared around this time. But there was plenty on Deguello for old-time fans to dig, like the bluesy fave “I’m Bad, I’m Nationwide,” with its searing lead tones. The guitar solo in “She Loves My Automobile” quotes the Freddie King blues instrumental classic “The Stumble,” popularized by Peter Green in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. A double-entendre lyric to “She Loves My Automobile” is very much in the risqué R&B style of Forties great Louis Jordan. ZZ Top had managed to reinvent themselves for a new era while remaining firmly grounded in their blues roots.

But just to help smooth the way into this new era of ZZ Top, the band unleashed the greatest and most protracted PR stunt of its career: the beards. While on hiatus, Billy and Dusty had gotten out of the habit of shaving. Hanging with the Rasta men, Billy must have received extra encouragement to throw away the razor. And when they got back together Gibbons and Hill decided to keep the beard thing going. Despite his name, Frank Beard refused to participate. He does however, sport the occasional moustache and/or goatee.

The ZZ Top beards are rock’s greatest Mac- Guffin. A MacGuffin is a cinematic trick invented by the great director Alfred Hitchcock. It’s an object that captures the audience’s attention (a mysterious box, which may or may not contain a bomb, for instance) while key plot developments are snuck past the viewer in order to prepare a surprise ending. So here ZZ Top had appreciably changed their musical style and signed with a new label, but all anyone could talk about were the beards. Press for the album tended to revolve around beard jokes, beard cartoons, funny fake beards on people who weren’t in the band… From this moment forward, ZZ Top would be “those guys with the beards.”

And in growing those whiskers, they’d written themselves an unlimited musical license. They could decide to become a classical string trio or a trad jazz outfit and they’d still be “those guys with the beards.” As with the Worldwide Texas Tour, they’d taken some natural aspect of their lives and found a way to put it to creative use.

ZZ Top’s next album, El Loco (1981), continued in the vein of Deguello: clean, chorused/ phased/flanged guitar tones and rampant double entendres. You don’t have to be a lit major to catch the phallic references in “Tube Snake Boogie” and “It’s So Hard.” “I Wanna Drive You Home,” could be an answer song to “She Loves My Automobile.” And “Pearl Necklace” is their famous poetic euphemism for fellatio.

THE WARNER YEARS, PHASE TWO (1983–1992): MTV’S MOST UNLIKELY IDOLS

The reinvention of ZZ Top really kicked into high gear on ZZ Top’s third Warner Bros. release, Eliminator (1983). The band’s most successful album ever, it is also their most controversial recording. Some longtime fans were horrified by their embrace of synthesizer and drum machine technology, not to mention their ascendancy on MTV, the then-brandnew medium that had become the domain of Duran Duran, Michael Jackson and Madonna. To this day Billy is loathe to talk about the electronic elements of Eliminator. “My guitarcollecting, screw-counting buddies don’t want anything but tube amps and Pearly Gates,” he says, visibly squirming in his chair.

But the controversy over the instrumentation on Eliminator tends to overlook a more important point: the album contains some of the best songs the band has ever written. “Gimmie All Your Lovin’ ” is perhaps the hookiest, most infectious thing in the entire ZZ Top canon. It’s not that far removed, lyrically or melodically, from “It’s Only Love,” a highlight of the cowboy hat period. And, like it or not, Eliminator classics like “Gimmie All Your Lovin,’ ” “Legs” and “Sharp Dressed Man” had an enormous impact on the popular culture of the early Eighties and are the songs for which ZZ Top will most likely be remembered in 100 years.

“‘Legs’ wouldn’t be ‘Legs’ unless it had that driving synth bass,” Dusty Hill points out. “We wrote the song with that in mind. We wanted it to be a big part of the song.”

“It was a brand-new day, in terms of how records were made,” Billy adds. “And guess what? We were listening to and liking records made using this new technology. Take one of my favorite bands at the time, Depeche Mode: they were producing some of the heaviest stuff I ever heard. Some people didn’t get it, but I think that was a perceptual thing. You look onstage and see a guy singing. And behind him there’s three guys with black boxes. But where’s the drums? Where’s the guitars and amps? There was an assumption on the part of some that the music couldn’t be heavy without drums or guitars. But man, you crank some early Depeche Mode on a big sound system with some giant subwoofers, and it’s some of the heaviest stuff ever.”

Those who focus unduly on the presence of synths and drum machines on Eliminator are also overlooking some of the most inventive and downright nasty guitar work Billy F. Gibbons has every laid to tape, or any other recording medium, for that matter. The album was created at Ardent, the same studio that produced Fandango and Tejas, and ZZ Top were doing exactly what they did on those albums: going crazy with the gear they found in Ardent’s storage rooms.

“When we went back into Ardent after our hiatus, the storage vault for gear had increased threefold,” Billy recalls. “And the uncharted rooms had all this weird new stuff: new amps, studio gear and things with keyboards, but they had knobs on them. Like, ‘That looks like a piano, but it sure ain’t no piano!’ So there was a timely, unplanned and unexpected coupling of this unknown world of new gear with what we knew. What we focused on was making good, solid tempo the new champion of the groove.” Meanwhile, Billy’s own vintage amp collection had increased exponentially. “I began collecting the 2x10 Fender Dual Professionals. We had found a bunch of them. They were 18-watt amps, and like all vintage gear—particularly tube amps from the Fifties—each one I found was a little bit different tonally. We also just loved the sound of Fender Champs, Harvards, Princetons, Pros, Bassmans, Tremoluxes... And we said, ‘Why restrict it to just one? We may find a combination of a few of these amps that works.’ ”

However, this proved a logistical nightmare when it came to miking so many amps. Thus, Billy’s infamous “amp cabin” came into being. “Instead of lining up 10 or 15 amplifiers with a mic on each one,” Billy explains, “or having to move a mic each time we wanted to try a different amp, we built a square of amps all facing inward, with one microphone in the middle. And we put a second stack of amps on top of those—all different ones. The idea was, Let’s put every type of amp on there. As for the third row of amps, we didn’t want them to get too far from the mic, so they were put on top, aiming down. And somebody said, ‘Looks like a little ol’ cabin,’ so we named it the amp cabin. We had one of every odd, previously unused amp in this structure, just to see what would happen. This was an extreme example of ZZ Top learning how to experiment with different things.”

But it wasn’t all small combo amps on Eliminator. “One of the great tonal combinations,” Billy says, “is a 100-watt Marshall, either single cabinet or a stack of two, and a solid-state Vox Super Beatle. The Super Beatle does something that the Marshall didn’t, and vice versa. But combined, the sound is really rich. I’m pretty sure that ‘Gimmie All Your Lovin’ ’ and ‘Sharp Dressed Man’ enjoyed that combination.

“Another oddball amp we had was a Legend 50, a 50-watt 2x12 combo made by a company called Legend Amps. It had a raw wood cabinet with a cane grill. That became a cornerstone amp on Eliminator. That was part of the formula. It consistently sounded good.”

As for guitars, Billy says, “Pearly was always present, and there was a Dean guitar that worked consistently. It was a weird half Explorer, half Flying V Dean, but with a small body. It was a tuning nightmare. Hours at a time. But it sounded really good. Besides that, there was always a Fender Esquire at hand. I’ve got two favorites, a ’51 with a black pickguard and a ’56 with a white guard and bigger neck.”

The title Eliminator comes from drag racing. It’s a term for the winning car in a race, the one that eliminates the competition. The Eliminator is also the name of an actual car, a heavily customized early Thirties coupe that Billy had created in tandem with a small army of automotive chop artists. His passion for wildly customized guitars is equaled only by his fascination with tweaked-out automotive custom jobs. The Eliminator coupe is depicted on the cover of the Eliminator album and it became a main protagonist in the series of video clips that the band created for the Eliminator singles: “Gimmie All Your Lovin’,” “Sharp Dressed Man” and “Legs.”

It was the early days of MTV. The channel had been created in 1981 around the concept of showing music videos nonstop, all day long. There was a shortage of material in those early years, and the clichés of rock video hadn’t been invented yet. ZZ Top were initially unsure if they should even enter this new medium. As Billy has pointed out, they’re hardly fashion models. But he had an idea. Rather than make the group the focus of the video clips, he decided to fill them with the things he loves most: hot cars, bizarre custom guitars and sexy chicks—the main components of the male American dream.

It a sense, the ZZ Top videos are all MacGuffins. They’re filled with eye-catching distractions that draw attention away from the three aging rock and rollers who actually created the music. In that regard, they do the opposite of what a music video is supposed to do: spotlight the artist. Ironically enough, it proved to be a wildly successful formula.

“We decided, ‘Why don’t we let the story tell itself?’ ” says Dusty Hill. “And let’s have some girls in there to look at. We’ll be more observers and advice-givers or whatever. The girls were a real easy decision to make. I didn’t hear a ‘no’ vote anywhere.”

And so three grizzled sidewinders who had been around since the days of love beads and Nehru shirts found themselves prominent members of the new, Eighties pop pantheon, sharing the limelight with pretty-boy synth bands and singing, dancing disco divas. In keeping with the eternal generosity of the freak circus called rock, the bearded misfits were accepted with open arms. Eliminator went 10 times Platinum.

The Eliminator coupe morphed into a hotrod spacecraft on the cover of Afterburner (1985). The sound offers the same blend of Eighties synth sparkle and vintage mid-century guitar tone. Perhaps the trio was doing a lot of camping at the time. This was the album that gave the world “Sleeping Bag,” “Woke Up with Wood” and “Velcro Fly.” It also contained the only power ballad in the ZZ Top canon, “Rough Boy.” With cavernous, digitally detuned drums and layers of velvety synth chording, it was another huge hit for them: a slow dance fave, but also somehow believable. How else can guy who hasn’t shaved in eight years seduce a lady than by offering himself up as a “Rough Boy.”

“I don’t think we lost any male fans with that one,” Hill says, “but I think we got a lot more female fans. Women really liked ‘Rough Boy.’ ”

Recycler is the third and last in the series that Billy calls ZZ Top’s “-er” albums. Recycler is perhaps too aptly named. Synth-pop was dead as a doornail by 1990, when the disc was released, and the Eliminator formula, so fresh at first, was starting to sound mighty stale. The band seemed to realize it. Recycler’s most successful track, “My Head’s in Mississippi,” harks back to the bluesy grind of ZZ Top’s earlier days, while also hinting at what was to come. The guitar track features another Billy custom guitar, La Warpa, a surrealistically contoured cross between an Explorer and a Strat, equipped with a single humbucker.

Billy’s head had indeed been in Mississippi during that period. In 1988, he’d collaborated with Pyramid Guitars to create the Muddywood, a guitar constructed from a roof timber taken from the cabin in Mississippi where blues great Muddy Waters had been born. Once completed, the guitar was presented by ZZ Top to the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi, an institution dedicated to the preservation of blues traditions that the band had helped establish and continue to support. At the dawn of the Nineties, there was every indication that the synth thing was over. ZZ Top were ready to return to their roots.

THE RCA/BMG YEARS (1992–present): REFUGE IN THE HOME OF ELVIS

In 1992, ZZ Top signed a new record deal with RCA for what was reported in the trade press to be a whoppin’ great chunk of money, a phenomenal deal even for those wild, crazy, high-flyin’, Bill Clinton, dot.com bubble Nineties. A bonus for Dusty Hill was that RCA had been the label of his number-one rock and roll hero, Elvis Presley.

“Yeah, that was the reason we signed with RCA. It had nothin’ to do with the money,” Hill joked at the time.

ZZ Top’s first album for their new label was Antenna (1993), a stripped-down, lean-andnasty restatement of the core ZZ Top values: gritty blues and the sound of steel strings amplified through vintage tubes. The title of the album paid homage to the lawless Texas radio stations that had inspired Gibbons, Hill and Beard when they were kids.

Rhythmeen (1996) came next. It too is a raw and bluesy outing, but as always, Billy had a few twists to add to the plot. “During the recording of Rhythmeen,” he explains, “[producer] Rick Rubin had turned me on to one of his acts called Barkmarket. Wow. Just a scary band. And the guitar players’ favorite tuning was down to Cs and B, so we began experimenting with really low tunings. Rhythmeen is probably the best example of ZZ Top’s foray into the super-low frequencies. It not only changes the way you play but the way an instrument begins to sound. There’s a standard tuning, but who says so? It’s whatever you come up with.”

Billy’s fascination with collecting African artifacts began around the time of Rhythmeen. This, too, is reflected on the disc: several tracks feature African tribal percussion instruments from Billy’s collection, including massive log drums. Some of these currently reside in the front yard of the guitarist’s Hollywood residence, beautiful lawn sculptures that, like most African objets d’art, are functional as well.

“When we were in the studio recording the log drums,” Billy says, “the engineer kept coming on the talkback saying, ‘Is something broken in there? I keep hearing this rattle.’ We checked the drum kit, the guitars and amps, but finally we realized the sound was coming from the log drums. Inside we found these bits of rubber, shapeless chunks right from a rubber tree. Apparently they’d been put in there deliberately, to create this buzz when you hit the drum. So those African tribesmen, they knew about distortion, man!”

ZZ Top celebrated their 30th Anniversary in 1999 with XXX, another fine collection of Delta musings and double entendres, this time with a hip-hop influence thrown into the mix. The band’s most recent release is Mescalero (2003), a potent distillation of all that is intoxicating about ZZ Top. Against a grainy backdrop of dirty guitars, Billy sings in a sepulchral croak that could peel the paint off of Tom Waits’ barn. There’s even a leering, leather- lunged Dusty number, “Piece.” The disc brings the boys back to La Frontera—there’s the occasional dash of marimba, concertina and lyrics en Español—and the cover art replays the “Eliminator” video as a Mexican Day of the Dead cartoon. Though drunk and long deceased, the guy gets the girl and roars off down the highway. On the roadside, three bony hands flash the victory sign. Los Tres Hombres rock on.

POSTSCRIPT: BIG PLANS FOR THE FUTURE

At the time of this writing, Billy Gibbons is in the midst of installing a recording studio in the ground level of his Hollywood place. At the time I visited him, the project (or perhaps Billy’s marriage) was at a stage that necessitated that he camp out on the barren, exposed-brick ground level of the house rather than sleep in any of the beautifully appointed rooms upstairs. And so a mattress lay in the middle of the floor, with the strange paraphernalia of Billy’s unorthodox lifestyle strewn around it in every direction. There were vinyl records, CDs, high-tech computer gear, phone equipment, teddy bears, ketchup bottles, mailing tubes, sundry stationery items, cardboard boxes, boom boxes and, of course, guitar gear of every description. It looked like an adolescent boy’s messy bedroom or some kind of hippie squat.

Leading the way through the rubble, Billy outlined his plans for the place. His intention is to configure it identically to Foam Box in Houston, matching the gear and room acoustics as closely as possible. Doing this will make it easy for Billy to move his musical projects from place to place, following the ramblings of his peripatetic mode of existence. Among the projects he is planning are a solo album, an EP with his pal Keith Richards and a disc of ZZ Top classics as performed by the band today.

Will any of these recordings ever see the light of day? With Billy F. Gibbons, there’s no way of telling. That’s another one of the rules. But it’s nice to know that his hyperactive, uniquely creative brain shows no sign of slowing down.

“I always felt like that record could have been better if we had worked on it some more”: Looking for a blockbuster comeback album, Aerosmith turned to Van Halen producer Ted Templeman. For Joe Perry, it served as a learning experience

“It's like saying, ‘Give a man a Les Paul, and he becomes Eric Clapton. It's not true’”: David Gilmour and Roger Waters hit back at criticism of the band's over-reliance on gear and synths when crafting The Dark Side of The Moon in newly unearthed clip