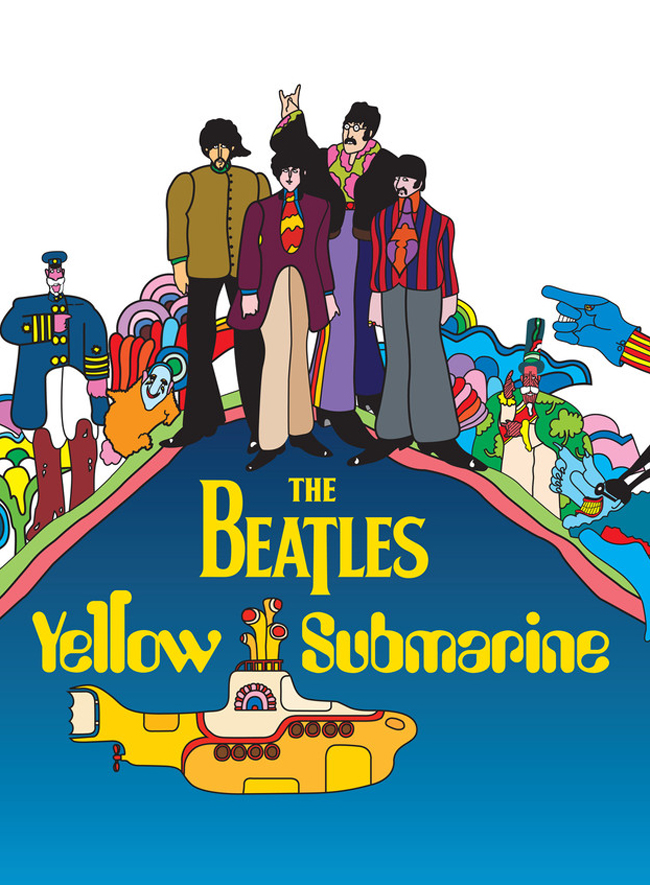

'Yellow Submarine' Sails Again: Director/Animator Bob Balser Recalls the Making of the Classic Animated Beatles Film

In 1967, American-born animator Bob Balser was working on a project in Spain when he received an invitation to fly to London and try his hand at designing animated characters based on the Beatles. The project? A full-length cartoon feature film called Yellow Submarine.

“They had to get started quickly, because they had a screening date set for July of the following year,” Balser recalls. “They had just one year to do an entire feature-length animated film.” The schedule was tight, and the budget was small: slightly less than $1 million.

But among the talents assembled for the film were special effects director Charlie Jenkins and celebrated illustrator and graphic designer Heinz Edelmann—not to mention the Beatles, whose music would be featured throughout and who would themselves make a cameo in the film. When Balser was offered the chance to work as a director on the film, he took it. “It was,” he says, “probably one of the best years of my life.”

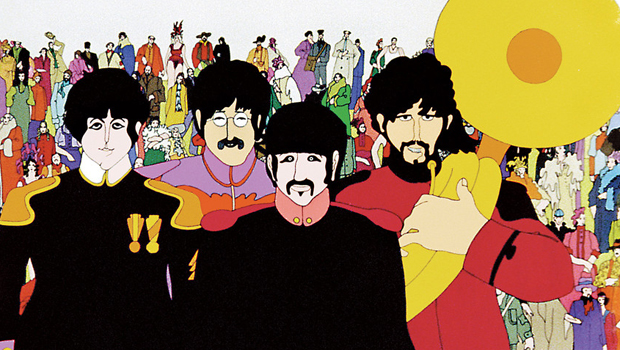

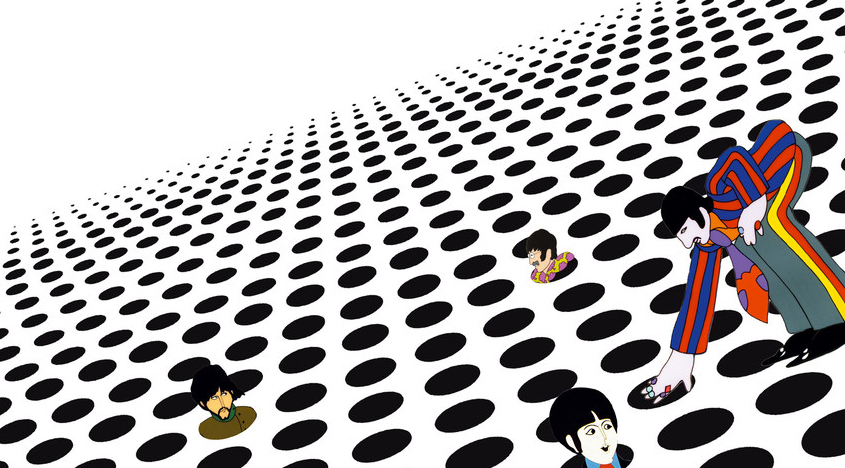

Yellow Submarine, of course, went on to become one of the most popular and influential films in the history of animation. When it premiered in 1968, audiences had never seen anything like. With its pop-art visuals, Day-Glo color scheme, and cast of bizarre characters and creatures, the film was like something out of an LSD trip. Subsequent releases on videotape and DVD were poor representations of the film’s original splendor, and are no longer in circulation.

Fortunately, Yellow Submarine, will sail once again when the film is reissued on DVD and Blu-ray this month. The new editions, to be released in the U.S. on June 5, have been restored frame by frame, entirely by hand, from the original hand-drawn animated artwork.

Both the DVD and Blu-ray releases will come with bonus features, including a documentary on the making of the film, audio commentary by producer John Coates and Heinz Edelmann, the original theatrical trailer, interviews with participants involved in the film, behind-the-scenes photos and reproductions of pencil drawings. In association with the film’s reissue, the Yellow Submarine soundtrack album—including the songs “Nowhere Man,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “All You Need Is Love” and the title track—will be reissued on CD.

The new restoration has been not only much needed but also much deserved. Nearly 45 years since it made its debut, Yellow Submarine remains a visual treat, with its brilliant design, rich color palette and frequently wondrous use of special effects such as rotoscoping and multiple exposure.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Ironically, for all of its cutting-edge animation and design, Yellow Submarine was the brainchild of two men who had worked on the decidedly downmarket TV cartoon series The Beatles. The program, a Saturday morning staple in the U.S. during the late Sixties, was created by Al Brodax and directed by George Dunning for King Features Syndicate. Brodax and Dunning had higher ambitions for Yellow Submarine, and set about assembling an international cast of animators and artistic talent for the film.

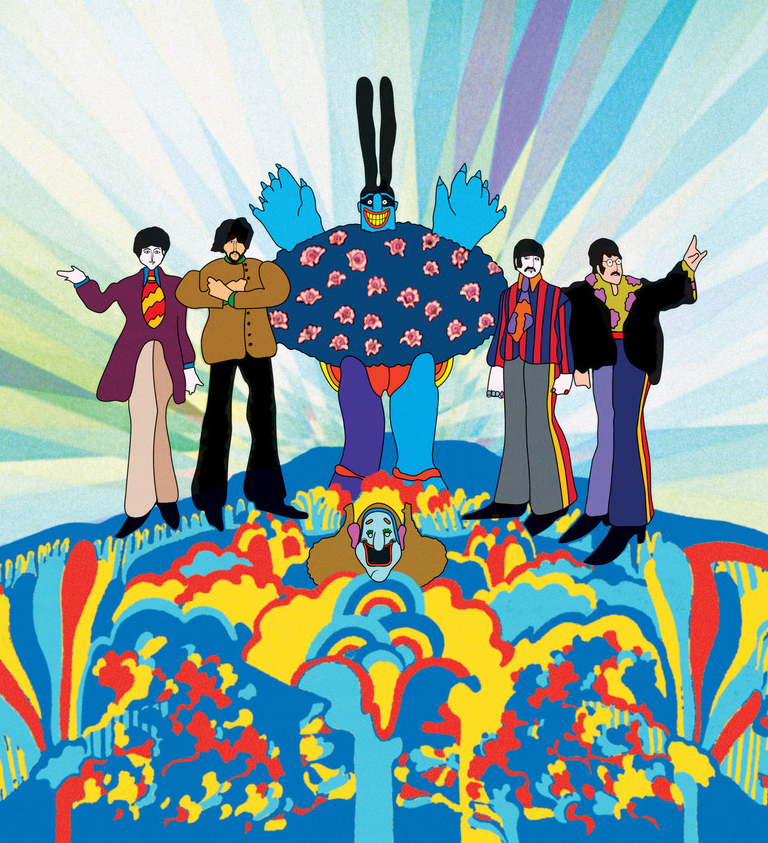

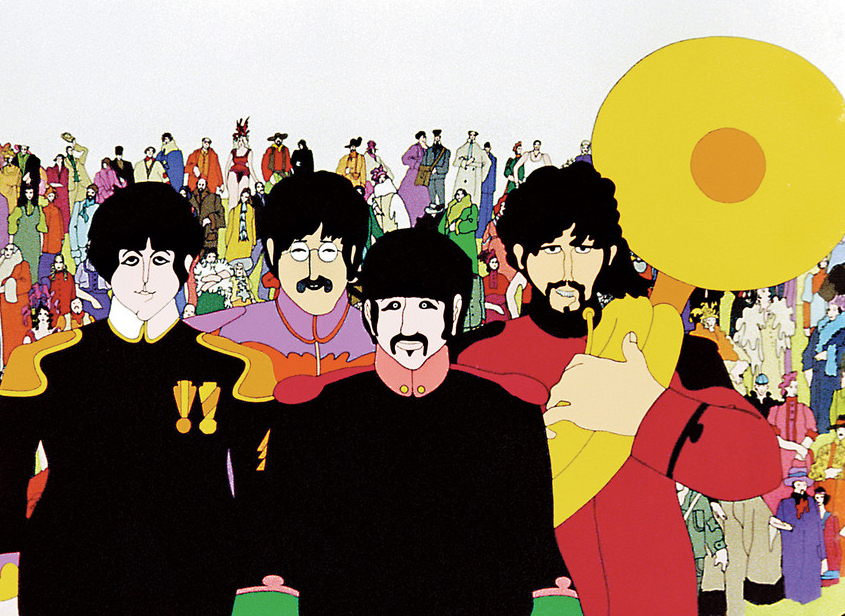

Balser recalls that Dunning originally planned the film as a series of 10 animated sequences set to the Beatles’ music. Eventually, the filmmakers decided on a plot about Pepperland, a musical fantasyland that is overdriven by music-hating Blue Meanies. Pepperland’s Lord Mayor sends an aged sailor named Old Fred off in a yellow submarine to find the Beatles and persuade them to help defeat the Blue Meanies and return Pepperland to glory.

Though the Beatles had allowed their music to be used in the film, they initially had no interest in the venture. They’d hated The Beatles cartoon series and figured a full-length King Features movie would be no better. At the outset of the project, they saw Yellow Submarine merely as an opportunity to fulfill their three-film contract with United Artists, which released A Hard Day’s Night and Help! (As it turned out, the Beatles’ brief onscreen appearance in Yellow Submarine was not substantial enough for United Artists to consider the contract fulfilled.)

Eventually, though, they were won over by Yellow Submarine’s highly original animation. “Once they came to see what we were doing, they were completely supportive of the film,” Balser says.

One of the few Americans to work on Yellow Submarine, Balser directed and storyboarded the scenes depicting the Beatles in Liverpool, where Old Fred finds them, and traveling to Pepperland through a number of seas, including the Sea of Nothing, where they meet “Nowhere Man” Jeremy Hilary Boob PhD. Though Yellow Submarine was Balser’s first feature-length film, he had previously worked on a number of award-winning commercials. Most notable among his early achievements is his work with revolutionary graphic designer Saul Bass on the innovative (and nearly seven-minute long) animated title sequence for the 1956 film Around the World in 80 Days.

On the occasion of Yellow Submarine’s new DVD and Blu-ray reissue, Balser took time out to talk with GuitarWorld.com about the making of this historic film.

GUITAR WORLD: How did you become involved in Yellow Submarine?

I had been working in Europe and had won a few prizes for some commercials. They were looking for people [to work on the film], and they invited what they considered were the eight or 10 best people in Europe to come to London and try out by designing and showing an animation style. There was sort of a common style of animation at that time, and [the Yellow Submarine team] wanted to break out of the mold and do something different.

Those of us who were invited to try out were asked to come up with a design for the Beatles’ characters. The film uses a huge variety of animation styles, and the biggest problem was finding a style with which to animate the Beatles themselves. For the trials, you didn’t have to do all four of them; they just said, “Do any character you like. We just want to see what you’re going to come up with.”

Before I went to London, they sent me home movies of the Beatles, and photos and so forth, so I had a lot of reference material to work from. What happened was that Charlie Jenkins, who brought me in on the project, also brought in Heinz Edelmann, who worked on [German publication] Twen magazine and was a very avant-garde artist at that time. Heinz’s original drawings for the Yellow Submarine animation were very beautiful, and when those came in, everybody said, “This is the style we want.”

So after they went with Heinz Edelmann’s design, they called me back in and asked me to be one of the unit directors. Well, it so happened that there were no units—there was nobody available to direct but me and Jack Stokes. [Stokes, along with Dunning, had directed The Beatles cartoon series and also designed the titles for the Beatles’ 1967 film, Magical Mystery Tour. He directed and storyboarded all the Pepperland scenes in Yellow Submarine.] We ended up being the only two directors on the film. This is what you call destiny, luck…god only knows!

What did your particular job entail?

I was basically directing my sequences in the film, but I did work on characters. I worked on the “Nowhere Man” character with Heinz Edelmann. When you’re talking about animation production, you’re talking about a team operation. It always is a collaborative situation. We had a basic team of maybe six or eight people who really set the style and planned and prepared the film, but we ended up with about 240 people working on the film. At the end of the film—and remember this is classic animation; there was no computer-generated images at that time—at the last minute, with the push to finish the film, they emptied out all the art schools in the London area and brought people in and worked them all night long to trace and paint animation cels.

What kind of changes did the film go through as it developed from concept to completion?

When I came in on the film, the day I started there was no script. Actually, there were lots of scripts but nothing was planned or accepted or prepared. George Dunning originally was going to do the film as 10 little short films that they would tie together with music.

How did the script come about?

We’d sit around and say, “We could do this and this,” and somebody would say, “Okay, that sounds good.” And somebody would scribble out some lines, we’d have a recording sessions and record the dialogue. Now, this is an hour-and-a-half film, but we must have recorded maybe a hundred, two hundred hours of dialogue. And it was not recorded just capriciously. We thought, Okay, this is what we’re gonna do, and then someone would say, “That’s not gonna work.” So we’d change the dialogue and plan another sequence and go back and record some new dialogue.

It’s been reported over the years that the Beatles were not interested in the film until they’d been shown a segment of it while it was in production.

That’s correct. They hated the Beatles cartoon TV series so much that it has never been shown in England. They hated the voices—you know, Hollywood actors imitating Englishmen—and they didn’t want to have anything to do with Yellow Submarine. George Dunning had worked on the Beatles cartoons, but his involvement I think was minimal.

George was tremendously creative; he did some fantastic films. I won’t say the Beatles cartoons were beneath him, but when you have a company, you just take whatever work you can get in order to keep your crew together so that you can eventually do the work that you want to do. He certainly wasn’t involved in the creative aspect of the series, but the Beatles didn’t know that. They thought Yellow Submarine was going to be more of the same—just like the cartoons, except longer.

Eventually, they came to see what we were doing. And when they saw what design Heinz had come up with, what the look was, what the people were pouring into it with their creative collaboration, they liked it. And, of course, then they said, “We want to do the voices.” But by the time they came in and said all of this, we were coming up to the end of the film, and there was no way we could record them. First of all, you can’t say to the Beatles, “We’re going to record at 10 o’clock in the morning,” and expect them to be in the studio.

Secondly, this film was done for just under a million dollars, and of that, $250,000 was paid to the Beatles for their live-action section in the film. So you’re talking about working on a shoelace. Recording their voices just wasn’t going to happen. As it turned out, the actors who were voicing their characters were all from Liverpool, and they captured the character of the Beatles perfectly.

I’ve read that the Beatles had contributed some plot ideas…

Nothing.

…that John had suggested the sequence early in the film when the yellow submarine is following Ringo down the street in Liverpool.

They may have said something to Jack Stokes or somebody on the project. But it was certainly nothing formal.

Were any of the sequences in the film particularly difficult or costly to create?

Yes, the sequence for “When I’m 64,” when the Beatles are traveling through the Sea of Time. It was late in the production and we were running out of money. Heinz Edelmann said, “I have an idea where we can do one minute of film very cheaply, just with numbers.” [The second half of the “When I’m 64” sequence consists of the numbers one through 64 illustrated in the film’s signature pop-art style.] Well, it turned out that was probably the most expensive sequence in the film. It was not as easy as just putting a bunch of numbers in there, because of the way it was animated, the way it was structured and so forth. But I love that sequence. That’s one of my favorites. Of course I love the “Nowhere Man” sequence, That was the first sequence that I storyboarded and that we put into work.

There had been nothing like Yellow Submarine in the world of commercial animation. Did you feel you were breaking ground with the film?

The biggest thing was that we were using lots of the techniques that had been used in experimental films leading up to this. And so this was a chance to have complete freedom to use all those techniques and incorporate them into the film.

Why would you have had that extra measure of creative freedom?

Because this being a Beatle film, nobody really cared what we did. Once the designs of the Beatles were approved, as long as there was Beatles music, King Features was assured it was going to be a success. As a result, nobody ever said, “No, you can’t do that,” or “You must do this.” And also, we never had to say, “We’ve got to be careful about the content because of kids.” We just made and did what we felt was the right thing to do.

The British version of the film contained a sequence with the song “Hey Bulldog,” which was omitted from the U.S. version. Has that been restored for the new, restored release?

Yes. Actually, there were three versions of the film: There’s the English version, with “Hey Bulldog.” Then they wanted to change it for the American market, so I redirected the film for a version without “Hey Bulldog.” And then, in 1999, when they first restored the film, they put everything together from both versions. This is the film that you’re going to be seeing now, complete with all the scenes. And you won’t believe how good it looks. The restoration work on this is amazing. It really is a revelation.

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.

“I loved working with David Gilmour… but that was an uneasy collaboration”: Pete Townshend admits he’s not a natural collaborator – even with bandmates and fellow guitar heroes

“You’ve gotta lose the fuss. You grab the new guitar, you scratch it. Grab the key right away": Kiko Loureiro on why players shouldn’t be too precious about their guitars

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)