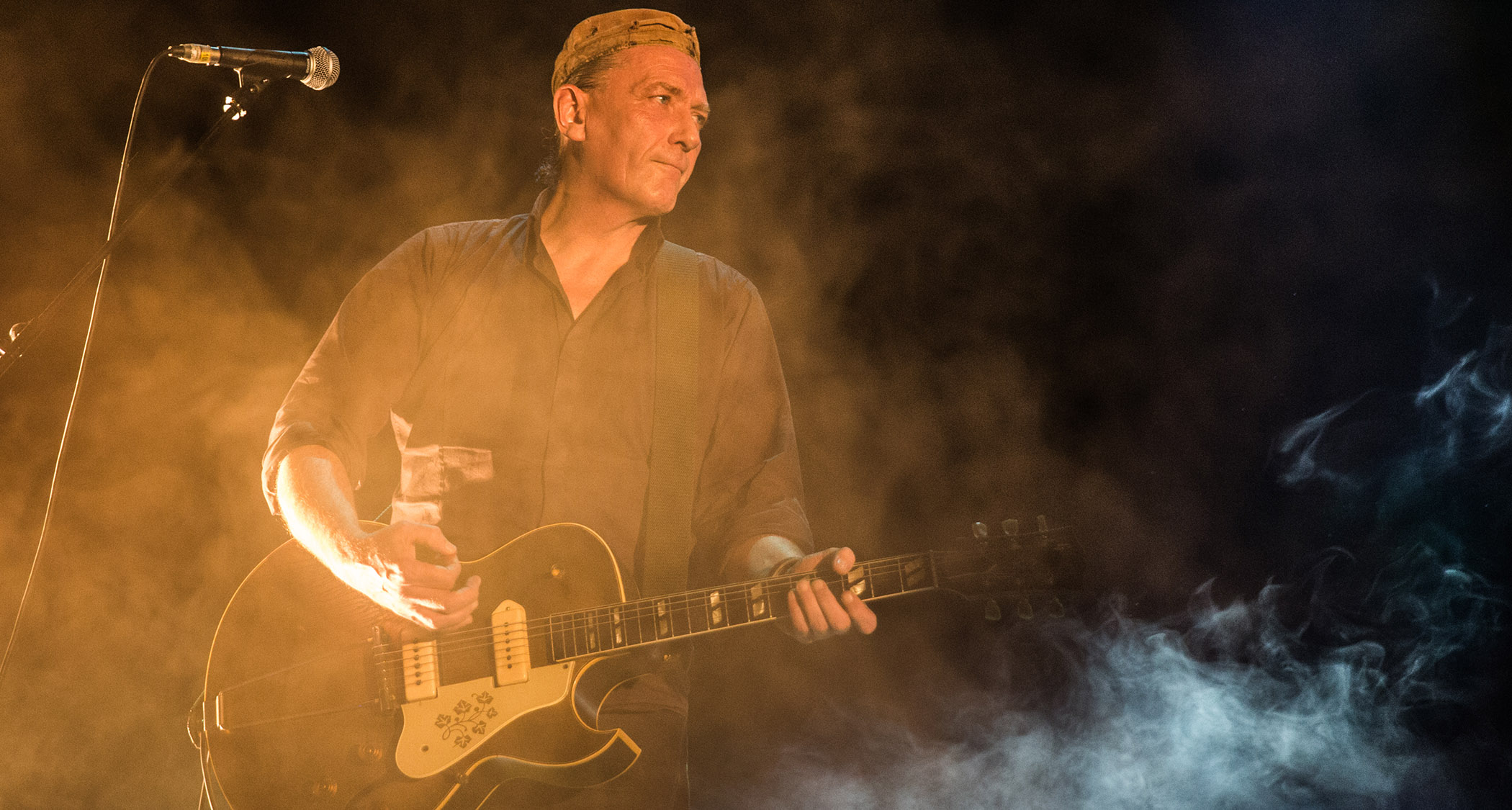

Xavier Rudd: “I am very connected to Country in a way that speaks through my music”

On his milestone tenth album, Xavier Rudd embraces culture, Country and community with inimitable passion

Born and raised in the coastal Victorian town of Jan Juc, Xavier Rudd has always been passionate about his spiritual connection to the Earth. Culture and community were ingrained in his soul from the second he first smelt a cool ocean breeze, and such has been a central theme of his music thus far. So for his milestone tenth album, Jan Juc Moon, Rudd endeavoured to embrace his roots more poignantly than ever before. And from the moment that the first gauzy, glittering synth on ‘I Am Eagle’ rings out, it’s clear he succeeded.

Don’t let the 70-minute runtime throw you off: on Jan Juc Moon, Rudd explores everything from twee folk-rock and sunkissed indie to kaleidoscopic psych-pop, whiskey-soaked blues and belting hip-hop. Imbibed with the influence of traditional First Nations music, it’s a riveting listen that, at the end of the day, feels oddly short. It’s no hyperbole to say that Jan Juc Moon is Rudd’s magnum opus – and he knows it, with plans to spread it to the farthest corners of so-called Australia on a 37-date road tour.

Before he kicks that off at the end of May, Rudd hung out with Australian Guitar to fill us in on the origins of Jan Juc Moon.

What made you want to really dig back into your roots for this record?

After 20 years of doing the overseas touring circuit, I took a break. And that’s when the pandemic started, so I hadn’t planned on making a record, but I felt like during that time, everything was so bizarre, the world changed so much. We were travelling – we went up to the cape, and we were in a pretty remote, country area, so whenever I’d come into civilisation, I’d sort of hear about what was going on. And I guess it was a state of reflection, y’know? Everyone was in this reflective period, wondering what was happening and where they were going, and where the world was at – and so I was I. I was reflecting back a lot on my life and my career... It was kind of like this big reset.

So I started writing the record in that frame of mind, looking back and reflecting on everything. ‘Jan Juc Moon’, the song, I wrote that… It would be more than ten years ago now – around when I recorded the Spirit Bird album, I actually recorded a version of that song but I never released it. And so that came back up for me. It felt like the right time to re-record that track, and then it ended up being the title track.

So did the rest of this record sort of bloom from the revitalised ‘Jan Juc Moon’?

Not really. I had already been writing a bunch of music when I revisited the old recording of that song. I’d been thinking about a lot of stuff. But when I wrote that song, it was a difficult time for me. I was down in Jan Juc at the time, I was living down there and there was this massive moon – the scientists were saying back then that it was the biggest moon we’d ever seen at the time. I was going through a bit of a tough time, and just staring up at that moon, I felt like everything was getting pulled away by it. It was like this big moon was just dragging me away from everything I knew.

It was taking me away from my son, and that was tough; there was a lot of family stuff happening then. And when I recorded [the new version of ‘Jan Juc Moon’], my fourth boy was in the womb. I recorded his heartbeat from ultrasound, when he was still in the belly, and I actually used that throughout the track. So that was kind of cool for me – it was like this new breath, a new beginning for a new decade – all that stuff really came into focus around that song and my re-recording of it. It was a very ‘full circle’ kind of thing, and that’s when I thought, “Yeah, I’m going to call this record Jan Juc Moon.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Having made this record, do you feel like you now have an even stronger bond with your culture and heritage?

Yeah, look, my heritage is unknown. It’s been printed that I’m Wurundjeri, but we don’t know that. My great grandmother was taken from a Wurundjeri country, but we don’t know anything about her – it’s an ongoing journey, but it seems to get misprinted all the time from that story. It’s a personal search that I’m on, to find our history there. I definitely feel the presence of my culture in the music, and I am very connected to Country in a way that speaks through my music.

Often, the spirit that comes through my music doesn’t feel like me. It feels like it comes from another place – it’s relatable when I’m writing music that’s about, or comes from an emotional place in me, and it’s pretty clear that it’s me, or something that I’m feeling, but then sometimes there’s all this other music that comes through me, that just feels like it comes from somewhere else. I attribute that to spirit, ancestors, whatever – and I respect that. I think the spirit of this country resides in all of my music. But y’know, it’s so hard to put that into words – what that is, or who that is, or whether it’s related to me – those questions are always there, but I kind of treat it like it’s separate to me.

I have this huge amount of respect for the spirit in the music, but the way I treat it… It’s like if you were to take your grandmother to church – you just take her to church, you wouldn’t tell her what to wear, y’know? It’s kind of like that for me – I let the music come through me, and I try not to let my ego get too involved. I try to just let it be pure and just be a vessel for it. And then on this record, I was able to link up with other mob – there was some Bundjalung mob who shared their traditional song on ‘I Am Eagle’, which was really beautiful. And then J-MILLA was the perfect artist to come in and do his verse for ‘Ball And Chain’, based on what that song is about. They were the only collaborations I had on the record, and they were perfect. I did everything else myself, which I hadn’t done for a long time.

This record runs for over an hour, but it’s so musically diverse and expansive that it could be twice as long and still feel short. Where do you glean all the inspiration for these sonic detours?

I don’t know – they just sort of come to be, y’know? I’ve always made music, since I was little, and I’ve never really been one to sit down and write a song. They just sort of come to me, as I’m doing whatever. And I’m not really very strict with it, either – I kind of let it flow, and if an idea stays with me, then I’ll eventually produce it. Sometimes a song will be floating around in my head for a year before I even take it to an instrument. I’ve got to construct things in my mind first, and I’m in no rush, usually, to take them anywhere. The ideas that disappear from my head, I don’t really care about those, because I feel like the ones that are meant to stay will stay. And then eventually I get to a point where I think, “Alright, it’s time to dump this stuff out.

Ellie Robinson is an Australian writer, editor and dog enthusiast with a keen ear for pop-rock and a keen tongue for actual Pop Rocks. Her bylines include music rag staples like NME, BLUNT, Mixdown and, of course, Australian Guitar (where she also serves as Editor-at-Large), but also less expected fare like TV Soap and Snowboarding Australia. Her go-to guitar is a Fender Player Tele, which, controversially, she only picked up after she'd joined the team at Australian Guitar. Before then, Ellie was a keyboardist – thankfully, the AG crew helped her see the light…

- Ellie RobinsonEditor-at-Large, Australian Guitar Magazine

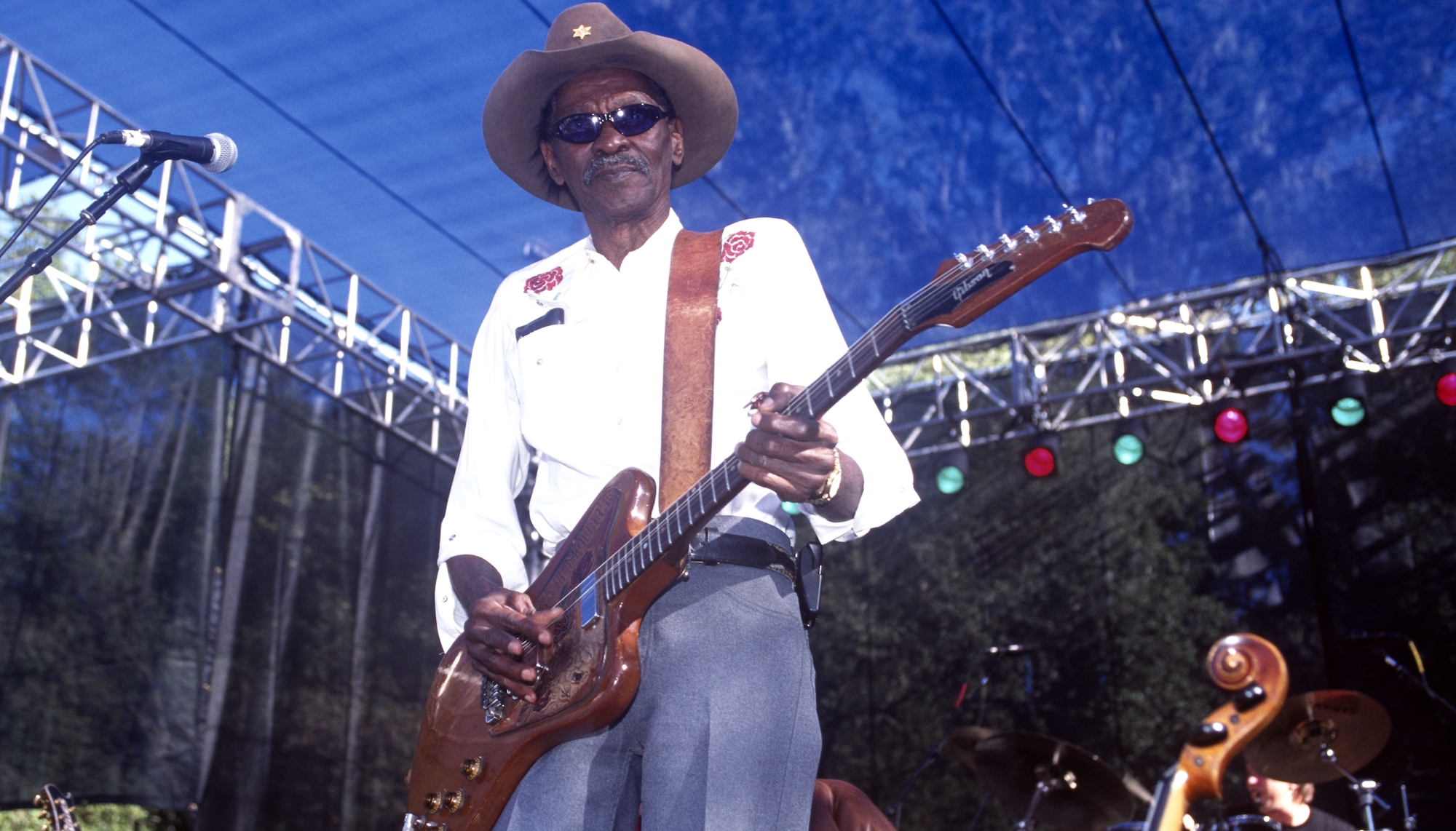

“Chuck Berry's not a very good guitar player. He's a clown. He runs all over the guitar, just like any one of these old rock players would do, and makes no sense”: Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown pulled no punches when speaking about his fellow guitar heroes

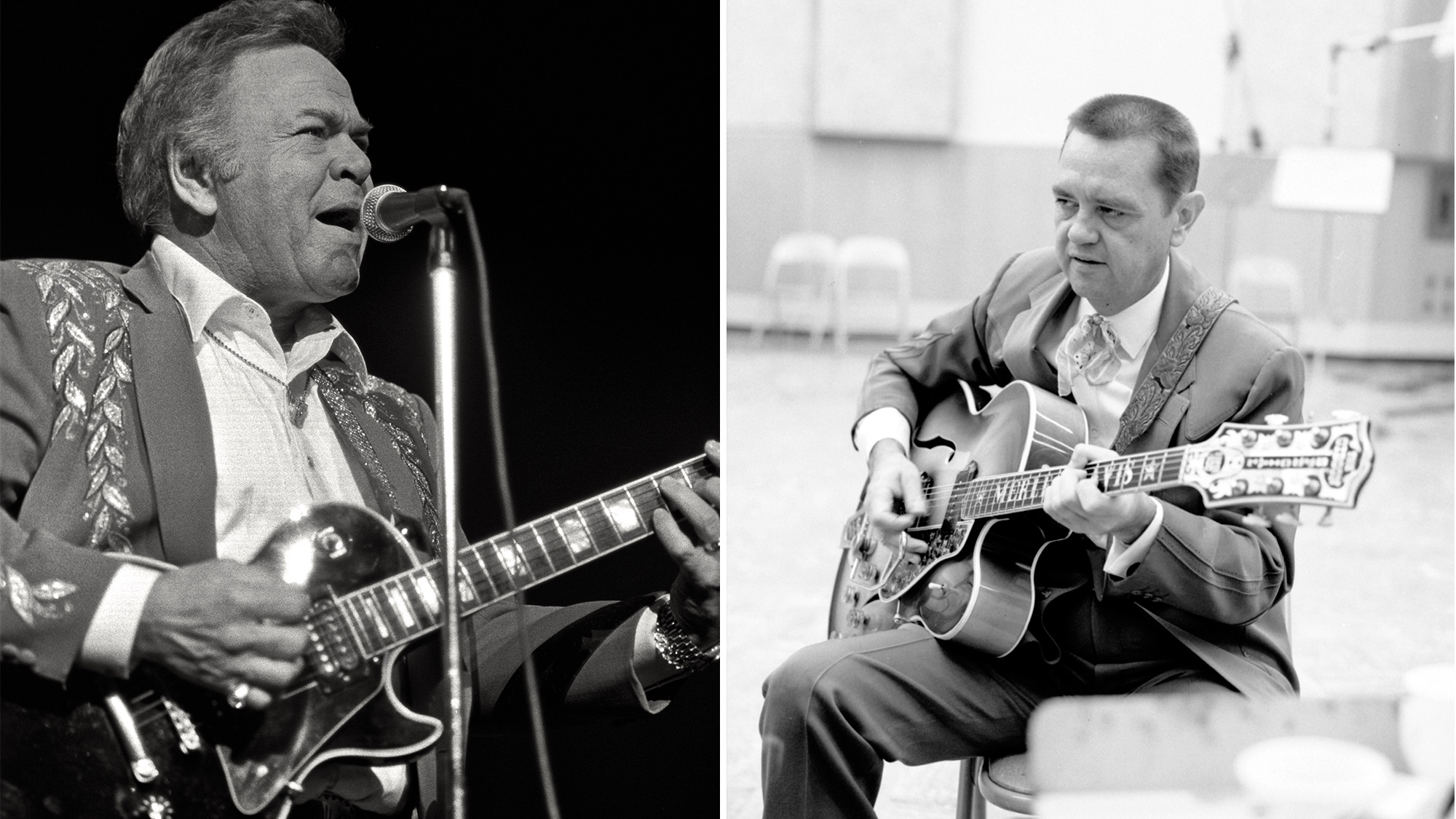

“I said, ‘Merle, do you remember this?’ and I played him his song Sweet Bunch of Daisies. He said, ‘I remember it. I've never heard it played that good’”: When Roy Clark met his guitar hero