Woodstock 1969: High Times

Originally published in Guitar World, September 2009

For three days in August 1969, America´s youth culture came together

for Woodstock, an event that marked the peak of the country´s counterculture revolution. On the eve of its 40th anniversary, Carlos Santana, Pete Townshend, John Fogerty and other guitar heroes recall their moments at the world´s greatest music festival.

At 5:07 p.m. on Friday, August 15, 1969, rock and roll’s greatest gathering of artists got underway in an alfalfa field, no less, located in upstate Bethel, New York. The hills of the land sloped downward like a great bowl, into a flat plain, as if nature had created her own amphitheater. In this respect, geology had set the stage for an event of monstrous proportions. Now, on this particular evening, humanity was doing its part to make nature’s gift a counterculture experience that would, figuratively and literally, take a young and vibrant generation, in the words of folksinger Joni Mitchell, “back to the garden.”

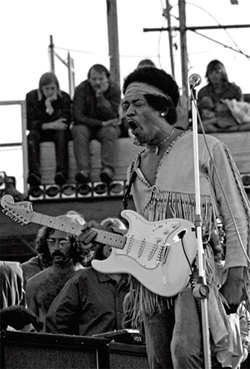

The event was Woodstock, the music and arts festival that signaled a paradigm shift in modern Western culture. Subtitled “An Aquarian Exposition,” Woodstock was billed as “3 Days of Peace and Music.” Over its course, from the evening of August 15th to the early morning hours of the 18th, nearly half a million people, most of them in their early twenties, came together for a weekend of peace, free love and music (along with the various substances that frequently go with them). More than 30 artists played at Woodstock, including some of the Sixties’ greatest and most influential performers: Creedence Clearwater Revival, Sly & the Family Stone, the Grateful Dead, Joan Baez, Santana, the Who, Crosby, Stills & Nash, and, most memorably perhaps, Jimi Hendrix.

But for America’s counterculture youth, Woodstock was more than a symbol of sex, drugs, and rock and roll—it celebrated a new way of living and looking at the world. In this and other respects, Woodstock was a seminal event that epitomized the ways in which the culture, the country and the core values of an entire generation were shifting as the Sixties came to an end.

The previous year had been as tumultuous and divisive as any of the 20th century, marked in blood by the assassinations of Martin Luther King and presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, and the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The Vietnam War was still raging, even as public favor began to turn against it. Many of the twenty-something male members of Woodstock nation lived in fear of being drafted and sent across the world to fight in a war they didn’t agree with. But in this one glorious weekend, the new generation found its voice in a celebration that demonstrated not money nor hostility nor anger but freedom, harmony and serenity via a potent brew of folk, blues and rock and roll.

None of this came easily. Dreamed up by two musically oriented hippies, Michael Lang and Artie Kornfeld, and funded by two young businessmen, John Roberts and Joel Rosenman, Woodstock turned out to be a bigger event than its planners had ever dreamed. The location was moved twice, with many area landowners protesting the staging of a music festival that would bring an onslaught of dirty long-haired hippies into their midst. The festival might not have happened at all were it not for an 11th-hour rescue by a dairy farmer named Max Yasgur. Persuaded by his son, Yasgur negotiated a deal that allowed Woodstock’s founders to set up on a parcel of land at his dairy farm in rural Bethel, not far from the real Woodstock, New York.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The challenges didn’t cease once the festival got underway. A change in weather brought downpours and a steady drizzle that drenched the unsheltered crowd. Food shortages and unsanitary conditions developed as the audience grew beyond the number anticipated. For the performers, the difficulties came in ongoing weather-related delays that kept many of them waiting hours to perform. And still the show went on, peacefully, despite every attempt from man or nature to stop it.

Woodstock has continued to live on in the American conscience, thanks in great part to two multiple-disc albums of music from the festival and the Michael Wadleigh–directed concert film. As we approach the event’s 40th anniversary, the time is right to revisit this signpost that pointed the way from the polite rock and roll that defined much of the Sixties to the unrestrained hard rock that infiltrated, then permeated, America’s mores and psyche in the early Seventies. In this exclusive oral history, Guitar World looks back at the memorable guitar performances that took place that weekend—from Richie Havens’ legendary opening set to the Who’s thrilling and triumphant conquest of an American audience to Jimi Hendrix in one of his most memorable and incendiary onstage moments.

Friday, August 15

Woodstock got underway Friday evening with a mix of famous and lesserknown folk artists. Among the former were folksinger/guitarist Joan Baez, Lovin’ Spoonful guitarist/singer John Sebastian, blues folk artist Tim Hardin, and Arlo Guthrie, son of American folksinger Woody Guthrie. But many of the day’s performers, including Country Joe McDonald, folk-pop flower child Melanie, Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar, and traditional folk artist Richie Havens, would find fame via their Woodstock appearances.

First up was Havens, who took the stage to play for the gathering throng. Much of the audience was late in assembling, largely due to the immense amount of traffic that clogged the surrounding roads and led to the eventual closing of the New York State Thruway. Havens was originally scheduled to perform late on the bill, on Friday night, but since he had the least equipment and could get onstage the fastest, he was pressed into service. Performing his own songs as well as a medley of Beatles hits, Havens played well past his allotted 20 minutes. Though he tried to leave the stage, festival organizers insisted he continue performing until another act could be found that was ready to play. Havens was back onstage when, he says, “I really had an inspiration.” It resulted in a spontaneous improvisation from which came his classic song “Freedom.”

RICHIE HAVENS I looked out over the audience and I said, you know, “Freedom isn’t what they’ve made us even think it is. We already have it. All we have to do is exercise it. And that’s what we’re doing right here.” So I just started playing, you know, notes, trying to decide what am I gonna sing, and the word “Freedom” came out. And that led into [the traditional black spiritual] “Motherless Child.” And then there was another part of a hymn that I used to sing back when I was about 15 that came out in the middle of it. And that’s how it all came together.

By the time Havens finished, festival artist coordinator John Morris had persuaded Country Joe McDonald to take the stage. McDonald and his band, Country Joe and the Fish, were slated to play Woodstock on Sunday, the 17th. For now, however, Morris needed a performer, and Joe, hanging around backstage, was pressed into service. Playing as a solo act for the first time, Joe was inexperienced at holding a crowd’s attention without a band behind him.

The audience roundly ignored him, until he got a radical idea that would produce one of Woodstock’s defining moments. At Fish shows, the band would get the crowd going with the “FISH Cheer,” an audience-participation chant performed in the style of cheerleaders at sports events. At Woodstock, Joe decided to rouse his indifferent audience with an inflammatory variation on the cheer just before launching into his jangly anti-war tune “I-Feel-Like-I’m- Fixin’-to-Die Rag.”

JOE McDONALD At our earlier shows, we’d shout, “Gimme an F, gimme an I,” and so on. “What’s that spell? FISH!” When we played the Schaefer Music Festival in New York City, our drummer got the idea to change “FISH” to “FUCK,” and we did it for the first time there.

I did it again at Woodstock: “Gimme an F, gimme a U, gimme a C, gimme a K. What’s that spell?” It established a mood, a political and social credibility for the Woodstock generation. Prior to that the attitude of protest music was “Try and be polite about it, try not to be offensive.” But the “FISH Cheer” at Woodstock was an energizing moment. I kicked into my folksong singer mode and segued into “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” and the crowd was mesmerized.

Saturday, August 16

In a weekend of few expressly political moments, Country Joe’s performance stood out as something special. And it was just the beginning of the revolution that Woodstock would give birth to.

While Friday night had been designed to induce good vibes and a peaceful mood, Saturday was calculated to ramp up the festival to a new level of excitement. A remarkable host of hot rock, blues and soul acts were scheduled for the day, including Santana, Canned Heat, Mountain, Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Sly and the Family Stone, the Who and Jefferson Airplane. These were among the most anticipated acts of the entire festival, as the large influx of new attendees demonstrated. Roughly 200,000 people had been expected to attend Woodstock, but by Saturday that number had clearly been exceeded. When the surging crowds overwhelmed the ticket collectors, the organizers announced that admission was now free. A chain-link fence was cut open, and the masses poured into the field.

By then a new complication had developed: rain had begun to fall, turning the trampled alfalfa field to muck. Saturday afternoon brought a brief respite from the storm, but by then, the summer heat, food and water shortages, sanitary problems, sheer boredom and overcrowding were beginning to take a toll on the attendees. If the promoters lost the goodwill of the audience, they would have lost everything.

Rescue came from an unlikely and unpremeditated source—a man and a band named Santana. Carlos Santana was unknown at the time, and his group’s debut album was still a month away from wide release. As a result, no one in the audience knew the songs Santana performed, including “Waiting,” “You Just Don’t Care,” “Savor” and “Jingo,” as well as the song that established them as superstars at Woodstock, “Soul Sacrifice.” How an unknown band came to play at the festival was remarkable. At the time, Santana were part of the thriving San Francisco rock scene and a favorite of Bill Graham, owner of the Fillmore East and Fillmore West concert venues. They were the only group to headline the Fillmore West without having made a record. Not surprisingly, Bill Graham was behind their Woodstock appearance.

CARLOS SANTANA Bill was approached by Michael Lang to help him out, because Bill certainly had experience putting concerts together. Bill had a fascination and an obsession with us, like he did with the Grateful Dead. He said to Lang, “I’ll help you, but you’ve got to put Santana on.” They didn’t know us from Adam, but Bill stuck to his guns and they let us play.

It’s always a compliment to be on the same stage with Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone, Ravi Shankar, Richie Havens, and of course everybody else. But Jimi and Sly were just on a whole other level; we knew that they had different kinds of spirits hovering around them. But everybody else—I felt that we could give them a good run. At that point we had been opening up for Janis Joplin in Chicago, and Paul Butterfield, and we saw how the band was taking the audience. They would boo us because they wanted to hear more Janis Joplin, but as soon as we played, they went, “Oooh! More!” All of a sudden, the women started discovering spiritual orgasms. They started dancing and their eyes rolled back to their ears. And they were laughing and crying and dancing at the same time, pretty much like a Grateful Dead concert. So we had confidence that we had brought something else to the table.

It’s always a high to remember the sound. I heard it before it came out of my fingers; then I heard it come out of my fingers and into the guitar strings, to the amplifier and to the P.A., and then from the P.A. to a whole ocean of people. And then it comes back to you. You never forget that. That’s where I discovered my first mantra: “God! Please help me stay in time and in tune!” I was totally peaking on mescaline, because they had told me I didn’t have to play until two o’clock in the morning and we ended up playing at two in the afternoon. I just repeated that mantra, and it got me through our performance.

Like Santana, Mountain were relative unknowns at Woodstock. The festival was only their fourth appearance together, but guitarist Leslie West and bassist Felix Pappalardi were an impressive duo. West, a New York native, had made a name for himself as a hotshot guitarist, while Pappalardi had crafted his career as a producer, most notably for Cream. The two men met when Pappalardi produced a record by West’s previous band, the Vagrants. When Leslie decided to go solo, Pappalardi was brought in to produce his debut solo album, called Mountain in reference to West’s then-substantial girth. By the summer of 1969, Felix began playing bass in concert with Leslie, accompanied by drummer N.D. Smart and keyboardist Steve Knight. This was the quartet booked to play Woodstock on Saturday night after Canned Heat, the band that had followed up Santana’s set.

LESLIE WEST We flew up in our own helicopter. Unfortunately, because I was much heavier at the time, the helicopter pilot did not want to fly one trip, so he took us up in two trips.

We were scheduled for Saturday night. We got a great time period, but since we got up to Woodstock earlier that day, we had to hide until it got dark, because they would have put us on sooner, since some of the bands before us weren’t ready to play. It was chaos in the beginning.

We went on at night, just as scheduled. But at about two or three in the morning, after we’d played, we were starving. [Mountain manager] Bud Praeger’s wife had given him six barbecued chickens to bring to the show. He didn’t want to take them; he told her, “They have food there, they have everything for the entertainers.” Well, that was gone in the first hour—Janis Joplin ate everything. So we were starved. There was nothing, and then Bud whips out these chickens! There were people coming up to eat it, ’cause it smelled pretty damn good. I think we fed 48 people that night.

Joplin performed after Mountain, turning in a loose and reportedly drunken performance that resulted in her omission from the Woodstock album and the original film (though one of her songs appears in the 25th anniversary director’s cut). Still, her presence at the festival was well known. On the other hand, few people today know that her set was followed by a performance by the Grateful Dead, largely because the world-acclaimed jam band was neither on the Woodstock soundtrack albums nor in the movie. The same was true of the follow-up act, Creedence Clearwater.

Ironically, while Woodstock’s freewheeling style was ostensibly in sync with the Grateful Dead’s laid-back jam shows, they were unhappy with the festival and with their own performance, which was plagued by technical problems and the band’s discomfort with the disorderly atmosphere both backstage and onstage. Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead’s late guitarist, described the experience in an interview some years after the festival.

JERRY GARCIA Woodstock was a bummer for us. It was terrible to play at. We were playing at nighttime, in the dark, and we were looking out to what we knew to be 400,000 people. But you couldn’t see anybody. You could only see little fires and stuff out there on the hillside, and these incredible bright spotlights shining in your eyes. People were freaking out here and there and crowding on the stage. People behind the amplifiers were hollering that the stage was about to collapse—all that kind of stuff. It was like a really bad psychic place to be when you’re trying to play music.

We didn’t enjoy playing there, but it was definitely far-out. It was like I knew I was at a place where history was being made. You knew that nothing so big and so strong could be anything but important, and important enough to leave a mark. I was confident that it was history.

John Fogerty certainly agreed with Garcia’s appraisal of the Dead’s performance. The leader of Creedence Clearwater Revival, Fogerty griped that the Dead “gave a sleepy performance” that caused the audience to slumber before Creedence could hit the stage. Not that Fogerty and his band needed to score at Woodstock—they had already made a name for themselves with hit records that had placed them at the top of AM radio charts, all without sacrificing their credibility with the hip FM radio crowd. Naturally, Woodstock’s promoters were eager to get CCR on the bill. In fact, the band was the first big-name attraction that agreed to appear at the festival, which helped to draw additional top acts.

While a band of such stature rightly should have gone on during prime-time concert hours, Creedence found themselves pushed back in the schedule just like every other band. They didn’t come onstage until late Saturday evening, after the hour-long, problematic Grateful Dead set. Unfortunately, the technical gremlins continued during CCR’s performance, affecting the sound of the guitars and bass for at least half of their set, which included such hits as “Born on the Bayou,” “Green River,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Proud Mary” and “Susie Q.”

Despite the problems, one good thing came out of CCR’s performance. In the months after the show, Woodstock’s persistent deluge inspired Fogerty to write “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” which mixed images of what he observed at the festival with dark, brooding reflections about American involvement in Vietnam. The song raced up the pop charts in the winter of 1970. Today, Fogerty cryptically introduces it in his solo concerts, saying, “I went to Woodstock, then hitchhiked my way home, then wrote this song.” At the time, however, the perfectionist Fogerty was disappointed with the band’s performance and claims that, for this reason, he refused to have CCR included in the Woodstock movie and album.

JOHN FOGERTY We didn’t do very well at Woodstock because of the time segment and also because we followed the Grateful Dead, and therefore everybody was asleep. It seemed like we didn’t go on until two a.m. Even though in my mind we made the leap into superstardom that weekend, you’d never know it from the [film] footage. All that does is show us in a poor light at a time when we were the number-one band in the world. Why should we show ourselves that way?

CCR’s fame notwithstanding, the most anticipated act of Saturday was the Who (though technically speaking they actually performed Sunday, given the late hour). The British group was an international sensation in 1969, thanks in no small part to Tommy, their groundbreaking rock opera. Woodstock’s organizers were desperate to get the group on the bill, though, reportedly, upon their arrival the Who insisted on being paid $11,200 before they would play. Perhaps part of their irritability was due to the late hour of their performance. Thanks to the day’s delays, the Who didn’t take the stage until 4 a.m. They started their set with a pair of songs that included their early hit, “I Can’t Explain,” before launching into Tommy, playing a slightly truncated performance of the record, including its hit tracks “Pinball Wizard” and “See Me, Feel Me.” With singer Roger Daltrey out front posing like a Summer of Love Titan, the Who enthralled the sleepy crowd to a new level of excitement.

B

ut by then, Townshend was grumpy about the late hour. Given the guitarist’s penchant for smashing his axes onstage, most people would know better than to get on his bad side during a performance, but that’s just what political activist Abbie Hoffman did. As a volunteer in one of the medical tents, Hoffman had been consuming large amounts of LSD to keep himself awake. Festival organizer Michael Lang suggested Hoffman take a break, chill out and enjoy the Who’s set from the side of the stage.

It turned out to be a bad idea. As the Who concluded “Pinball Wizard,” Hoffman, still under the drug’s effects, stalked across the stage, grabbed a microphone and began a political rant against the proceedings. Townshend cut him off, yelling, “Fuck off my fucking stage” and proceeded to hit Hoffman with his guitar, sending the dazed activist into the front pit as the audience cheered. “The next fucking person who walks across this stage is going to get fucking killed,” Townshend fumed moments later. It was one of the festival’s rare episodes of anger. But even that could not mar the Who’s performance, which provided one of Woodstock’s most definitive moments, as Roger Daltrey would later describe:

ROGER DALTREY The sun coming up to “See Me, Feel Me” was the top. I mean, that was an amazing experience. As soon as the words “See me” came out of my mouth, this huge, red August sun popped its head out of the horizon, over the crowd. And that’s a light show you can’t beat!

To me, the success and importance of Woodstock was that it was a triumph for humanity. The audience was the star of Woodstock. We were the catalyst that brought them there, but this was the first time that this young generation had got together in such numbers. American youngsters at that time were under incredible pressure from the Vietnam War, and it made people in power take notice. That was the importance for me at Woodstock.

Townshend has a different memory of the event, which isn’t surprising given the Hoffman incident and the lateness of the Who’s performance.

PETE TOWNSHEND Woodstock was horrible. It was only horrible because it went so wrong. It could have been extraordinary. I suppose with the carefully edited view that the public got through Michael Wadleigh’s film, it was a great event. But for those involved in it, it was a terrible shambles, full of the most naïve, childlike people.

What ultimately alienated the Who from our fans was the way Woodstock turned us into superstars in a clutch with Sly & the Family Stone, Ten Years After, Santana, et cetera. In some ways that was wonderful: we went from being a band with a predominantly male following to one where Roger seemed to be like a new kind of rock sun god. And we had a few women in the audience for a change.

But in other ways it was disarming, because the natural, easy connection between me, as the writer, and the audience was broken. “Baba O’Riley” [from the 1972 album Who’s Next] is about the absolute desolation of teenagers at Woodstock, where everybody was smacked out on acid and 20 people, or whatever, had brain damage. The contradiction was that it became a celebration: “Teenage wasteland, yes! We’re all wasted!”

Sunday, August 17

In terms of music styles, the final day’s lineup was the most varied of the festival. Artists like British singer Joe Cocker, guitarist Johnny Winter and Paul Butterfield each delivered his own distinct forms of blues rock. The Band, critically acclaimed for their work with Bob Dylan and their albums Music from Big Pink and The Band, performed their signature style of country rock. Crosby, Stills & Nash, riding high on the success of their self-titled debut released just three months before, played acoustic and electric sets, with new, but unbilled, member Neil Young sitting in on many of the songs.

Other acts on this day included jazz rock group Blood, Sweat and Tears, Fifties-style rock-and-roll revival group Sha Na Na and, the festival’s final performer, Jimi Hendrix. Billed as “the Jimi Hendrix Experience,” the lineup actually consisted of Hendrix backed by Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell, bassist Billy Cox and guitarist (and longtime Hendrix and Cox pal) Larry Lee, with additional performers rounding out the lineup.

But the band that had the most to gain that day was a little-known English group called Ten Years After. The quartet’s name came from the fact that the band got going “10 years after” the beginning of rock and roll, but their true roots went back much further than that, to the classic blues of Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, Sonny Boy Williamson and similar artists. At a time when these masters were being ignored in their own country, they were being lionized by British musicians, including Eric Clapton, Fleetwood Mac, the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds and Savoy Brown.

To this mix, Ten Years After brought a heightened level of intensity, stamina and indefatigability. Much credit was due to guitarist Alvin Lee, who was described as having the fastest fingers on the planet. His raw tone and style were key to the group’s sound and credibility among electric blues players and enthusiasts, and his playing helped induce hysteria among audience members. Still, only a small percentage of U.S. rock fans knew of Ten Years After when they performed at Woodstock. That was about to change.

For the show, Lee played his cherry-red Gibson ES-335 embellished with peace-sign decals, the same guitar he used from the band’s 1967 debut and well into his subsequent solo career. The group’s set included their lascivious version of Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Good Morning, Little School Girl” and their own songs “I May Be Wrong, But I Won’t Always Be Wrong” and “Hear Me Calling.” But the pièce de résistance was the set closer, “I’m Going Home,” a performance that raised the audience’s level of excitement and joy to a new level. The song became a highlight of the subsequent Woodstock soundtrack album and film, raising Ten Years After to star status and securing Alvin Lee’s place in the pantheon of guitar heroes.

ALVIN LEE Woodstock was just a name on a date sheet. We were in the middle of a tour. It meant nothing to us until we got there and they said, “You can’t get there by vehicle, you have to go in by helicopter.” And that was the first inkling that it was going to be a different sort of day.

After going on at three in the afternoon, we ended up playing for about an hour. It was a pretty high-energy set. That’s what Ten Years After is all about: to boogie down, have a good time and play lots of riffs around, and that’s basically it. I thought a lot of the things being said from the stage were embarrassing. They were all going on and going, “Oh wow, man, we’ve got a whole city here,” and that kind of stuff. I think it’s best to go on and say, “Let’s have a good time, rock and roll, bang the drums and just boogie down.” That’s my message.

It was some 12 hours after Ten Years After performed that Crosby, Stills & Nash went onstage, with Neil Young accompanying them on some of the songs. By then the audience was starting to thin out. Hunger, filth, incessant rain and general exhaustion had taken their toll, and undoubtedly many attendees hoped to depart before the roads became clogged again with traffic. But the numerous people that remained were among the first ever to see Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young perform together. As individuals, each had made a name for himself: Crosby with the Byrds, Stills and Young in Buffalo Springfield, and Nash with English pop group the Hollies. Together, however, they were a force to be reckoned with. Though Young had joined so near to the Woodstock performance that he barely considered himself part of the band, rock’s newest supergroup arrived at the festival less to perform than to be coronated as the hippies’ new reigning kings.

LARRY JOHNSON (Woodstock sound supervisor) Neil didn’t want to be in the movie. He didn’t want to be filmed, so you can only see his arm. At that point and time he was a sort of add-on to CSN; they hadn’t actually become “& Young” yet. It was only the second gig they had played live. Young felt that he was a sideman and didn’t want to be a part of it. He felt, “You can film those guys,” and that’s just how he is. I don’t know if he regrets that now or not, because we could’ve certainly have used the footage.

STEPHEN STILLS Our equipment almost didn’t get there. We were going to use a potpourri of the Jefferson Airplane’s and the Band’s equipment to play, but it showed up just in the nick of time.

DAVID CROSBY It was incredible. It’s probably the strangest thing that has ever happened in the world. Can I describe what it looked like flying in on the helicopter, man? Like an encampment of the Macedonian army on the Greek hills, crossed with the biggest batch of gypsies that you ever saw. I’m asked about Woodstock so often I usually feign only a dim recollection of it. But the truth is my memory of it is very good. I loved it. I thought it was a very heartfelt, wonderful, accidentally great thing where a lot of incredible music got played. There was a genuine feeling of brotherhood among the people who were there.

Due to weather-related days and a desire to have the crowd exit in an orderly fashion, Sunday’s show was extended into Monday morning. By the time Jimi Hendrix appeared, most of the attendees were on their way home. Hendrix—wearing jeans, a white leather jacket with heavyduty fringe, and a pinkish red scarf, wrapped around his carefully coiffed Afro—stepped onto the stage and introduced his ensemble, an untested band assembled just weeks before and about to make its first-ever performance.

BILLY COX [Hendrix] got in touch with me and told me he needed my help very desperately. I just dropped everything here in Nashville and I went to New York and we got together. We did some other small jobs down in the Village and some other places. But otherwise we constantly stayed in the recording studio, coming up with ideas for songs.

We found out that there was this festival that was fixing to happen in Woodstock. We just thought it was going to be an ordinary event; we didn’t realize how astronomical it was going to be. We rehearsed in Chopin, New York, which is maybe 15 minutes away. We got together with Larry Lee, a guitar player who was a friend from years gone by, Mitch Mitchell, Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez on congas, and Jimi and myself.

The band played a dozen songs that morning, including “Message to Love,” “Spanish Castle Magic,” “Foxey Lady,” and “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return).” Although the crowd had thinned to about 30,000, according to one estimate, Hendrix played as if the festival was at its peak. In a sense it was, thanks to his incendiary show, which culminated in Woodstock’s high point: his solo performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

COX I remember specifically when he did “The Star-Spangled Banner.” If you listen to the first five or six notes, I’m playing with him, and then I said, “Wait a minute, I better get out of this—we didn’t rehearse this.” And what a performance! What a solo! I’ve never heard another to compete with it. We did not have a set list; we just followed Jimi’s lead. We never rehearsed that at all. I will never forget that, and that will always stay with me and be on my mind.

Three songs later, Hendrix was done, and Woodstock was history, immortalized in not only its albums and film but, more significantly, the empowerment of a generation and the transformation of society.

“This particular way of concluding Bohemian Rhapsody will be hard to beat!” Brian May with Benson Boone, Green Day with the Go-Gos, and Lady Gaga rocking a Suhr – Coachella’s first weekend delivered the guitar goods

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour