Women in lutherie: how female builders are rewriting the rulebook and pioneering new guitar design

Going behind the scenes with esteemed builders Linda Manzer, Kathy Wingert, Rosie Heydenrych and more

What connects Paul Simon, Carlos Santana and Milton Nascimento? Answer: they all own guitars made by the same pair of hands. Well into her fifth decade building guitars, Linda Manzer is one of the most esteemed luthiers of modern times.

A pioneer and inspiration to generations of other guitar makers, she creates instruments that command ardent fans, decent money and the occasional museum plinth.

Convention-defying flat-tops, archtops, sopranos, baritones, sitar guitars and jaw-dropping one-offs such as the 42-string Pikasso for Pat Metheny – Manzer’s oeuvre and impact are all the more remarkable when you consider she’s done what she’s done in a business that might at times appear to have operated a ‘no girls’ rule.

So, what makes Manzer – and other luthiers who chose to ignore that rule – tick? Boutique builders from North America and Europe reveal their inspirations, signature models, choice of materials and thoughts on working in a world where women are still out-numbered, though not outdone.

Linda Manzer – Manzer Guitars

It all started when…

“I went to the Mariposa Folk Festival, late 60s, and saw Joni Mitchell playing a dulcimer and went to buy one at the local folklore centre in Toronto and it was too expensive. The fellow there suggested I buy a kit for half the price and make one myself, which I did. That’s when the bug bit.

“I continued to art college in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I kept finding myself making dulcimers. I realized that making musical instruments, specifically guitars, combined my love of art, woodworking and music. I heard about Jean-Claude Larrivée in Toronto. After spending a couple of months trying to persuade him to hire me, he eventually did.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I learned how to make steel-string and classical guitars with Larrivée from 1974 to 1978. During my apprenticeship we made over 1,500 guitars. As his small company grew, I realised I preferred to work in a more solo environment. I felt it served the resulting guitar better as it would have one set of hands guiding its path.

“I studied with James D’Aquisto in 1983 to ’84 in his ’shop in Long Island, New York; I learned how to build archtop guitars from him. He had studied with John D’Angelico, so I was immersed in a workshop rich in history and tradition. It was a huge honour to work alongside him. From him I learned to trust my intuition.”

For me, the most important aspects are: how the instrument sounds, how it feels to play, and finally how it looks – in that order

Linda Manzer

What do you think other guitar makers will learn from you?

“I have been told that people like my design sensibilities and, more importantly, the sound and feel of the guitars I make. The secret sauce is the passion you put into it.

“I think those who ‘get’ my guitars sense a ‘feel’ I try to get into each guitar. Each guitar has a little bit of me in it. Technically, I match the woods as best I can so they work as a team.

“For me, the most important aspects are: how the instrument sounds, how it feels to play, and finally how it looks – in that order. It’s also really important to listen to the person you are building for. Ultimately, it’s their guitar, so I try to listen and bring their musical dream to life.”

How did you work out how to make extraordinary instruments such as the Pikasso you made for Pat Metheny?

“Through experimentation and boldly going where no guitar maker had gone before? [laughs] Luckily, I was a bit naïve about the complexity of what I was undertaking and therefore undaunted. I had an incredibly willing partner to work with in Pat Metheny. I am forever grateful for his inspiration and support.”

What are your main considerations when choosing tonewoods?

“I listen to each piece of wood with my eyes closed – tapping it. I’m looking for sensitivity and responsiveness. And stability. I know the woods are going to be thinned and then have braces added. You have to intuit what it can and will become. I read that Michelangelo said he was just chipping away stone to reveal the statue inside, and I sometimes feel I’m doing something similar with the wood.

“When I began building guitars there were no endangered wood species. I have enough aged wood to last a lifetime, but I am very concerned about what the future holds for next generations of builders.

“I am glad for CITES [Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species] designations of woods. And it’s great to see people using locally sourced woods, recycled materials and windfall. But I think there will have to be controlled forestation of musical-instrument wood. And the time to start that would be right now, as the best woods are 100-plus years old.”

What challenges, if any, have you faced as a woman in lutherie?

“When I began building guitars there were no women in the field at all to my knowledge. Being the only one meant I was the icebreaker at the front of the ship. It was exhilarating and tiring. I cut my own path in a very welcoming field.

“I still occasionally have to prove myself when I go into an unknown hardware store and have to convince them I know what I’m talking about. But at the last hardware store I went into there were more women working there than men. That kind of blew my mind in a good way.

“The challenges can be subtle, though. When I started out there were many bumps in the road and they potentially added up to say: ‘You’re not welcome.’ Luckily, I had two older brothers. The big eye-opener was when I was about eight and I wasn’t allowed in the tree fort because my brothers had a ‘no girl’ rule. I fought my way up the ladder and once I was in the tree fort I realised they actually liked having me there.

For years I was the only woman working at Larrivée. But the men I worked with in the mid-70s never made an issue of my gender

Linda Manzer

“That’s when I realised ‘girls’ could do anything. Yes, there would be issues in front of me – for instance, I don’t have the strength most men have, but I work smart. I discovered a thing called ‘leverage’. Very handy for lifting heavy shit. Problems usually have solutions.

“There are definitely fewer women than men in this field, but the numbers of women grow each year. I think it’s less intimidating than when I started.

“For years I was the only woman working at Larrivée. But the men I worked with in the mid-70s never made an issue of my gender and, in fact, probably became slightly protective about me, because they saw some of the stuff I was experiencing. These same fellows, the original six apprentices of Jean-Claude Larrivée and Larrivée himself, are my dearest friends and inspiration.

“We are better if everyone can enter the field they excel at or have passion in. This works both ways. Society should also welcome men doing traditional female jobs. We are all stronger if these artificial walls come down.”

Kathy Wingert – Wingert Guitars

It all started when…

“I needed a life change and a career direction. I loved playing guitar, but I was a terrible performer. A few life events ended with me standing in the middle of the library wondering what I was going to do. Some soul-searching and a card catalogue lead to books on guitar making and repair. The book was pretty awful, but it planted a good seed.

“The journey to my first guitar meandered through the search for suppliers and tools, a class at a junior college and a job at a workshop that specialised in high-level instrument restoration and repair. The owner was an expert in violin family instruments.

“He didn’t teach me methods but how to see and how to listen, how to do a really good setup, and a handful of things in construction. And how to be really, really snooty about wood.

“If you count the first instrument that I built, though, it was in high school. If you count all the years I bought, fixed and flipped guitars, that was all through my 20s. As for when I hung a shingle and started selling guitars as a career choice? That was 1996.”

What sets your guitars apart?

“It’s hard to stand out for fit, finish, aesthetics and originality, because there are so many truly fine builders doing perfect work. There are a lot of us who stand shoulder to shoulder about the things that mean the buyer will get a guitar that is worth what they pay.

“What sets mine apart, I believe, is the time I take to voice the tops, and the voice I’m going for – as dark as possible while being fully articulate. I’ve been accused of getting cello-like tones. My necks and setups are very good.”

Most of the great guitar makers I know were more driven by music, guitar and art than by exposure to woodworking

Kathy Wingert

Why so few women in lutherie?

“Women with children usually do most of the care. Guitar making takes a tremendous amount of time: there aren’t enough hours in the day for one of those things, certainly not both. Family roles are changing and there is a better division of childcare. I don’t know if that is playing out yet in guitar world, but it will.

“I suppose you were expecting me to say girls are less likely to hang out with their dads at the workbench, but most of the great guitar makers I know were more driven by music, guitar and art than by exposure to woodworking. And guitar has tended to be more popular with men than with women.

“At the dawn of the guitar, after it began to supplant the lute, it was very much a woman’s instrument. Over time, guitars got bigger – whether because men got interested, or if the fashion for larger instruments made it less appealing to women, I don’t know.”

Will more women in lutherie change the norm of ‘designed by men for men’?

“I assume so. But there’s a funny thing about girls with guitars. Have you ever noticed that when a woman takes the stage with a guitar, it’s likely to be big and well worn? I think women often feel that if they show up with a ‘girly-looking’ guitar, they have just increased the barrier to credibility.

“For years I would go to concerts and search the backup band for a woman ‘sideman’. Women could be stars, or they could be an all-girl band, but outside of orchestras it appeared a woman couldn’t just have a job playing guitar. Then I chained myself to the workbench and didn’t come up for air. When I finally did, I found the world had finally changed.”

Rosie Heydenrych – Turnstone Guitar Company

Finding out about Linda Manzer, among other female luthiers, encouraged Rosie Heydenrych, in her mid-20s, to sign up for a guitar-making class at London Metropolitan University.

She followed up with a two-year internship with a local maker, and volunteered with repairer Celine Camerlynck in London’s Denmark Street, before starting the Turnstone Guitar Company in 2015.

What sets your guitars apart?

“I’d like to say tone and playability, but that is for the player to identify. It’s exciting to use new woods, feel their differences in my hands and anticipate the contribution they will make to a finished instrument.

“I like to use different woods for bracing to emphasise tonal characteristics that a species excels at – walnut for warmth, padauk for clear treble, mahogany for crispness. I have become very interested in the use of English timbers [see more in the Winter 2019 edition of Guitarist Presents Acoustic].”

It comes down to wanting a better playing experience, so for women I think in terms of smaller guitar bodies, less weight in the instrument and easy playability on the neck

Does it matter that there are so few women in lutherie?

“Lack of diversity in any industry is a shame. Things are changing, but when I was at school I was the only girl in my year to take woodworking. I think to this day it still breeds an undercurrent of insecurity. I worried about what friends and family might think when I told them I was interested in working with hand tools, machines and glues.

“One of the first things I did was research if there were any female guitar makers, and I found out about Kathy Wingert, Linda Manzer and Judy Threet. It gave me the courage to walk through the door of that evening class.

“I see so many small women who are swamped by a dreadnought-size guitar. I don’t think women [guitar players] want anything that’s aesthetically different, but they do sometimes have different physical requirements. It comes down to wanting a better playing experience, so for women I think in terms of smaller guitar bodies, less weight in the instrument and easy playability on the neck.

“Being a custom maker I can help spec a guitar that caters physically to a person’s requirements. That goes for men and women.”

Angela Waltner – Waltner Guitars

“When I started, I was very exotic as a woman building guitars,” Angela Waltner, whose classical instruments sell worldwide, tells us from her base in Berlin.

“Today, it is more common. The classical guitar world is still dominated by men, but there are signs that future generations will be female. The instrument will benefit. But when it comes to the soul of an instrument, of music, it doesn’t matter whether I am a man or woman.

When it comes to the soul of an instrument, of music, it doesn’t matter whether I am a man or woman

Angela Waltner

“I can’t list all the great people who taught or supported me and I’m very grateful. To name one: from the late Benno Streu, a restorer of old Spanish guitars, I learned sound adjustment on the finished instrument, which is my specialism besides building guitars. Sonority, clarity and sound colours are attributes that characterise my instruments.

“Sustainability is very important to me. Classical guitarists are often conservative and expect rosewood in their guitars. Nowadays, several suppliers offer beautiful local woods that work very well.”

Claudia Pagelli – Pagelli Guitars

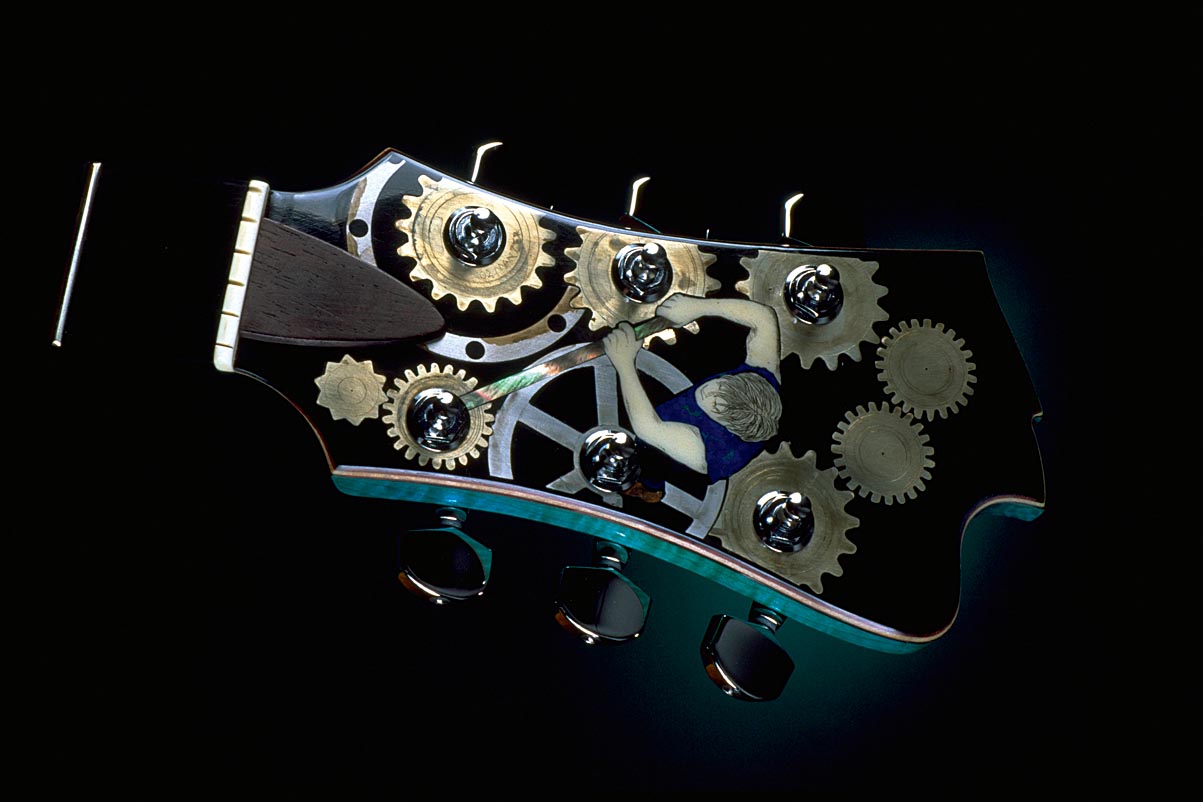

Claudia Pagelli designs guitars and husband Claudio builds them. Together, the Pagellis have been described as not so much top of their league but in a league of their own. Asymmetrical acoustics, open headstocks, even a stone soundboard – the wife-and-husband team long ago threw the rulebook out of the window.

“My apprenticeship as a decorative designer and graphic artist, my time at art school, and my various jobs in the creative field were an advantage when it came to guitar design,” says Claudia, a co-founder of the Luthiers Beyond Limits group.

“I wasn’t committed to guitar history, and I didn’t know how a guitar was constructed. So I have no limits when drawing or thinking of the end product. There is really no reason why a woman can’t work as a luthier.

“Their work has to be good and authentic, of course. Our experience is that women are very welcome in lutherie. A new male luthier has a harder time gaining a foothold.”

Joshia de Jonge – Joshia de Jonge Guitars

“When I first started, I think I knew less than five female builders. That’s beginning to change, but we’re still in the minority. People would assume my father was the builder, and later my husband.”

Celebrated classical guitar maker Joshia de Jonge has been steeped in lutherie since childhood. Her father, and teacher, is the luthier Sergei de Jonge, and sibling rivalry spurred her on, aged 13: “My younger brother started building a guitar and I was jealous and wanted to build one as well, so I did.”

She cites Linda Manzer and Grit Laskin among her inspirations, and credits renowned American luthier Eric Sahlin for the subtle twist she likes to plane into the neck for a comfortable playing position.

“All in all, the guitar making-world has been a really positive atmosphere for me,” says de Jonge. Her handmade instruments, also notable for her mosaic rosette, top bracing pattern and French polish, attract international stars such as Otto Tolonen from Finland and Welsh composer Stephen Goss.

Shelley D Park – Shelley D Park Guitars

Boutique builder Shelley Park describes her take on Gypsy jazz guitars as “a thoughtful modern interpretation of a classic design. It is my intention to provide the fit and finish expected by today’s acoustic player while respecting the work of Selmer-Maccaferri.

“I think my instruments offer playability and a sweet, nuanced tone while maintaining the responsiveness and projection these guitars are expected to have in a Hot Club swing context.”

Park worked at Larrivée then for fellow Canadian David Webber before setting up on her own ’shop in Vancouver, British Columbia, “a province where I have access to local materials, both softwoods for soundboards and hardwoods for backs and sides. I am always glad to work with local spruce, maple and walnut.

“I’m excited about some of the composite replacements for ebony and rosewood components and suspect they’ll start to show up in the instruments I build.”

She says: “I’ve never attributed my successes and disappointments in the guitar-making world to my sex.”

Martina Bartovka & Zuzana Jarjabkova – Dowina

Martina Bartkova’s grandfather was a carpenter, so she was naturally drawn to the hands-on, creative nature of guitar building.

Zuzana Jarjabkova, who works on necks and backplate design at Slovakia’s Dowina, believes that lutherie is still a man’s world.

The Dowina Bona Vida (meaning ‘good life’) is a parlour-style guitar, available in steel- or nylon-string versions, that uses granadillo, American walnut and cocobolo woods.

“My grandad was a carpenter and as a kid I spent a lot of time in his workshop, so I always liked manual work, being creative and making something of great utility,” says Martina Bartkova who has worked on binding, sanding, frets, dovetails and laser-cutting for Dowina in Slovakia.

“This is dirty work. There is a lot of glue, wood dust. I like my work, but I think not a lot of women are inclined to do this. Guys didn’t believe in me; I needed to show them each day I was capable.”

Currently working on necks and backplate design, Martina’s colleague Zuzana Jarjabkova aims to move on to design complete guitars. “Guitar making is still considered a man’s work. I don’t know if that is changing. But my colleagues changed, for sure.”

Would more women in guitar making have an impact on design? Jarjabkova is sceptical: “I don’t think design depends on gender.” But Bartkova thinks so: “Women have a different aesthetic sense,” she offers.