Why Canada is home to some of the world's most exciting hard-rock guitar players

The Dirty Nil, Monster Truck, David Wilcox and PUP offer a guided tour of the Canadian six-string scene

Alex Lifeson. Neil Young. Frank Marino. Jeff Healey. Canada has never had a shortage of guitar heroes. But for every six-stringer who braved the winter cold in their youth before going on to international fame and fortune, there are tons more who have settled for being beloved heroes at home.

The average American might not know who Paul Langlois and Robbie Baker are, but every Canadian can sing the intro riffs to Tragically Hip classics like Little Bones or New Orleans Is Sinking.

Over the past decade, Canada’s musical reputation has only grown – the world’s biggest pop star (Justin Bieber) and rapper (Drake) were both born and raised in the province of Ontario, as was the Weeknd.

But when it comes to rock, Canada has flown largely underground in recent years. During the early 2000s, an influx of guitar-based bands made the pilgrimage south to dominate American airwaves.

Sum 41 and Avril Lavigne were the darlings of the mall punks. Nickelback and Theory of a Deadman were beloved by aggro dudes and Metallica tribute aficionados.

And then, the heavy guitars from north of the 49th parallel went quiet. Sure, Canadian indie acts like Arcade Fire were big among the cool kids with interesting haircuts, and they technically had guitars as part of their sound, but they didn’t rock.

So what happened? Did the entire country forego Gibson Les Pauls and Marshall stacks to join accordion-heavy art collectives? Have we decided to change our National Anthem from O, Canada to Hotline Bling? The answer, of course, is no. Canada’s long legacy of hard rock and loud guitars is still strong.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“They say in England – reference to the '60s guitar scene there – that rainy cities make good guitar players. When you’ve got snow in cities, that gets amplified because you can’t leave the house at all,” says Luke Bentham, guitarist and singer for The Dirty Nil.

“I think there’s a lot of motivation to get together with your friends and play some loud rock and roll in the basement here. Especially living in Ontario, there’s complete times of the year when going outside, unless you have a strict purpose, is not an advisable undertaking.”

Judging by their output, the Dirty Nil did plenty of woodshedding during those frigid Januarys in their native town of Hamilton.

Their sound veers between the high-energy power chording of early punk like the Ramones, though there’s a sheen of catchy craftsmanship reminiscent of power-poppers such as Cheap Trick, all combined with a thinly hidden love of the harder stuff; the band’s shows often end with a spot-on take on Metallica’s Hit the Lights.

While the band has been kicking around for more than a decade, it’s only in the last few years they’ve started feeling the love in Canada.

At the 2017 Junos, they took home the award for Breakthrough Group, while their album Master Volume was nominated for Best Rock Album at the 2020 edition. (Canada doesn’t just have its own beloved rock bands, it also has music-industry infrastructure that’s uniquely its own.

The Junos are like the Grammys, except politer). Not that they haven’t had any success in the U.S. – they’ve shared bills with bands like Against Me! and the Menzingers. But Bentham credits their Canadian start for making their career possible.

If you get your own momentum going and prove you’re in it to win it, the government will assist you in going to play abroad

Luke Bentham

The country has extensive funding programs for young artists, allowing fledgling bands to record proper demos, shoot music videos and plan tours that would otherwise leave acts with a financial loss.

“We’re very fortunate to have the government-funding systems here to help us play abroad in our earlier years,” Bentham says. “If you get your own momentum going and prove you’re in it to win it, the government will assist you in going to play abroad.

“There are incentives that way that are really, really critical at a time when bands are making no money but have the drive to go do the thing.

“We’ve spent the majority of our time over the last seven years in the U.S. so we have a lot of American bands we’re friends with. They have their minds blown every time we talk about the whole thing. It’s almost like a myth in the U.S.”

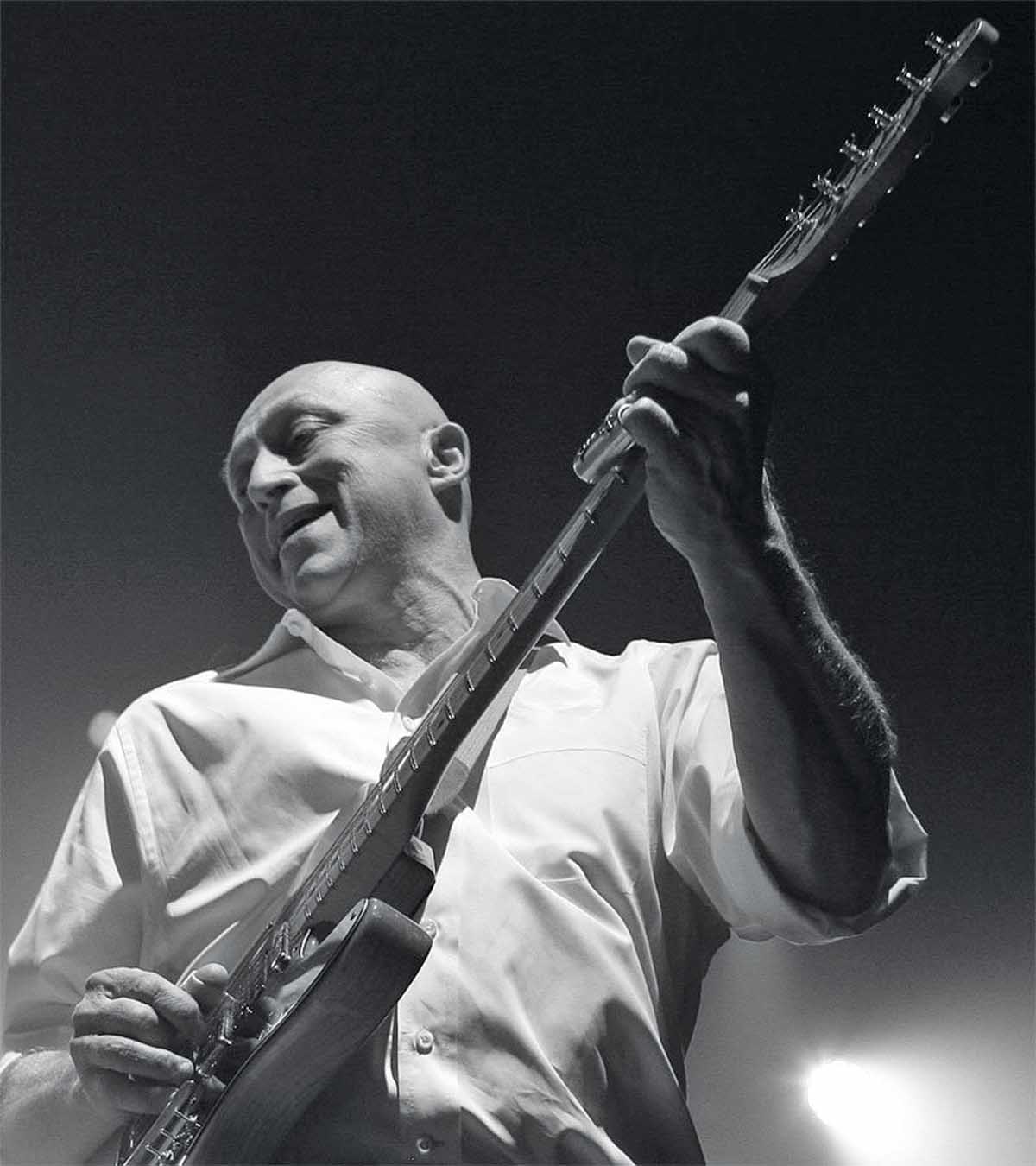

Of course, Canadian guitar heroes predate the grant system. At 70, David Wilcox has seen the evolution of the country’s music scene, from proto-rock up to the modern day.

Inspired by Elvis, he first picked up the instrument in the '60s and over the course of his long career collaborated with Canadian greats like Anne Murray and country-rock band Great Speckled Bird, as well as American icon Carl Perkins.

One of the things I’ve noticed with Canadian artists in different media is there’s a lot of individuality. Everyone from Neil Young to Joni Mitchell

David Wilcox

He then went off on a lengthy solo career, scoring hits with bluesy, off-beat tunes like his signature Do the Bearcat. Though originally from Montreal, he spent years in Toronto, witnessing the growth of one of the most under-appreciated guitar scenes in history.

“Toronto, for many years, has been a fabulous guitar town,” he says. “We had everybody from Lenny Breau to Ed Bickert, Liona Boyd, Donna Grantis. Sonny Greenwich, who lived in Montreal but came to Toronto frequently and was a favorite of mine.”

Despite that history, rock has become just as niche in Canada as anywhere else. The irony is that while a lot of young Canadians are able to pick up a Les Paul and make a career of it because of that financial help, some are seeing their greatest success elsewhere.

Power trio Danko Jones, for instance, has been pumping out barebones rock and roll for 25 years but has seen its greatest success in Europe. That’s a continent that Monster Truck guitarist Jeremy Widerman has become extremely familiar with over the past 10 years.

Also hailing from Hamilton, Monster Truck take the best bits of Deep Purple, AC/DC and pretty much every other classic rock band you can think of and smashes them together into a deliriously raunchy modern sound.

Where rock bands once ruled the radio and television roost in Canada, the genre has not only lost ground to hip-hop and pop but also lost some of the major promotional tools that got guitar rock to the people.

While there are still classic rock radio stations and festivals like Heavy Montreal to play, other support systems have atrophied.

Take MuchMusic, the Canadian take on MTV, for instance; whereas it was once dominated by music videos from huge-in-Canada acts like Our Lady Peace, Matthew Good Band, Sloan and, yes, Nickelback, it has since rebranded and become a lifestyle and comedy channel aimed at teenagers.

“We tour Canada once a year, and the whole infrastructure of the scene, whether it’s live music or the radio market or television or magazines, is kind of non-existent at this point,” Widerman says. “When I’m on tour, it’s mostly in the U.K. and Europe.”

And yet somehow a cohesive scene persists across the gigantic land, even as myriad rock bands all pursue dramatically different sounds. The Dirty Nil and Monster Truck count each other as friends. Bentham and his bandmates used to live with members of more roots-oriented rockers Glorious Sons and expressed solidarity with power-pop group Arkells.

Another band he counts as friends are Toronto’s PUP, who play a more aggressive, shout-y form of punk. Widerman credits Sum 41 guitarist Dave Baksh for giving invaluable help during Monster Truck’s early years; their 2011 EP Brown is named for the swarthy guitarist, who lent a ton of gear for its recording.

While there isn’t necessarily a well-defined Canadian sound, one thing many players have in common is a focus on subtlety rather than pyrotechnics.

“One of the things I’ve noticed with Canadian artists in different media is there’s a lot of individuality,” Wilcox says. “Everyone from Neil Young to Joni Mitchell to whoever. Partly because there’s a certain feeling of isolation in winter. I don’t know.”

I prefer guitar players who are able to tell stories through what they play

Steve Sladowski

“I prefer guitar players who are able to tell stories through what they play,” says PUP guitarist Steve Sladowski, who cites Mitchell and Bruce Cockburn as some of his favorite Canadian players.

“Even someone like Alex Lifeson is somehow an understated guitar player. Playing in Rush, in a power trio, he’s happy to play what needs to be there. There’s some way of playing this really technical music and really proggy but never overplaying.”

While the sounds might vary, one thing that unites guitar bands is the hours they spend slogging it out on Canada’s endless highways (when you calculate the distance between Canada’s big cities, it starts making a lot of sense that Tom “Life is a Highway” Cochrane is a canuck).

Sladkowski points to two other highly aggro bands who have managed long careers in the north as examples of the creative risks bands can take in Canada.

“The common thing that unites Fucked Up, Cancer Bats and us is touring,” Sladkowski says. “Fucked Up tour less now but the amount they grounded out on the road and the same for Cancer Bats and for us is what has allowed that sort of creative risk taking. It’s never been about selling records. It’s been about being on the road and willing to make the tremendous sacrifice that touring demands.”

Focusing on Canada as a market comes with its own challenges, though. With just 36 million people, many of whom are concentrated in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver and a few other large cities.

“The distance is insane. We know a lot of bands from the early 2000s that didn’t do a lot of work in the U.S. They focused on Canada and honestly, the Trans-Canada highway will break a band,” Bentham says. “It’s a long-ass distance. Especially when you get out of Ontario and head west, there’s just outposts between the major cities.”

Despite all the challenges, Canadians will still jealously guard their own. When the Tragically Hip played their last-ever concert in 2016, it was televised nationally and watched by around a third of the country.

When their singer, Gord Downie, died a year later, even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was among the very public mourners. For years, the Hip were touted as “Canada’s band,” but they aren’t the only ones who got promoted to a higher status at home than they ever did abroad.

Take, for example, a bill the Dirty Nil found themselves on last year. The headliners were Alexisonfire, a band who saw some success in the U.S. during the screamo boom of the early 2000s, but who are mostly known there for the City and Colour side project of singer/guitarist Dallas Green.

Between the two bands were pop-punk icons the Offspring – a surefire headliner if they were playing with almost any other band.

Part of the reason a band like the Hip or Alexisonfire can become absolutely massive in their home country and more of a cult band elsewhere is because of laws stipulating radio and television stations have to play a certain amount of Canadian content. But Widerman believes there’s more to it than that.

“It has a lot to do with being able to focus on a market,” he says. “We’re always going to have our stalwart markets in London (Ontario) and Ottawa and Toronto just because that’s where we are and the opportunities that arise from being geographically close, whether it’s radio stations, festivals or a fanbase connected to your band. There’s always going to be a little bit of a thing where we find ourselves at a festival and can’t believe the bands we’re gonna headline over.”

I’m not a huge humbucker guy and I’m not really a huge Les Paul guy, but when Tom Bartlett asked me to play this guitar, which is such a huge honor, I said yes. It’s a living piece of history

Steve Sladowski

If some idle hands spend the long winters noodling on guitars, others end up making them. While not home to a powerhouse like Fender or Marshall, there are ample boutique manufacturers for acoustics, electrics, amplifiers and pedals. Godin and Prestige make high-quality instruments.

Montreal’s high-end Greenfield Guitars have found their way into the hallowed hands of Keith Richards. Widerman credits amp manufacturer Yorkville and its subsidiary Traynor (which touts itself as the makers of “Canada’s sound”) as a major ally when it comes to helping out with gear.

It’s rare for musicians to dedicate themselves entirely to homegrown gear, but you do see rigs with a distinctly different flavor.

While Bentham and Widerman favor the classic combo of Gibsons into Marshalls, Sladkowski’s pedal board has a patriotic vibe, and he’s the current keeper of one of the two guitars built by luthier Tom Bartlett in 2013 that have been passed between acts like Blue Rodeo, the Tragically Hip, Royal Wood and Sam Roberts Band.

“I love Empress Effects; they’re based out of Ottawa,” he says. “I think there’s a really, really great history of luthiers and guitar building that’s finally getting its due. I’m playing the Maple Leaf Forever guitar right now.

“I’m not a huge humbucker guy and I’m not really a huge Les Paul guy, but when Tom Bartlett asked me to play this guitar, which is such a huge honor, I said yes. It’s a living piece of history.”

While the comfort of home is nice, and grants can be a great way to get a start in the music industry, there is an economic reality to coming from a country with one-10th the population of the U.S., the potential audience being that much smaller. True economic success means expanding that, and the U.S. is the biggest potential goldmine.

“Based on what some of our peers are doing in the U.S., if you could make some bread and butter down there, then that’s a really, really smart thing to do,” Bentham says. “We’re pretty determined to keep going to the U.S. because it’s been, after the last album cycle, quite fruitful. I love Canada, I love living here, but I grew up worshipping rock and roll. So America is a little bit central to that for me.”

It’s something we never want to take for granted, that this country has such an incredible infrastructure for bands that are from here

Steve Sladkowski

Even though all roads to megastardom and big money lead through the U.S., most bands will tell you that no matter how the crowds get in Austin or Milwaukee or Miami, there’s no place like home.

“Canada is the best market in the world,” Bentham says. “I love it. There’s so many cities that feel like a second home to us at this point.”

“We’ve played every province and we’re playing our first show in the Northwest Territories,” Sladkowski says. “It’s something we never want to take for granted, that this country has such an incredible infrastructure for bands that are from here. As much as we work elsewhere and spend a lot of time touring internationally, you can’t ever forget where you came from.”

Adam is a freelance writer whose work has appeared, aside from Guitar World, in Rolling Stone, Playboy, Esquire and VICE. He spent many years in bands you've never heard of before deciding to leave behind the financial uncertainty of rock'n roll for the lucrative life of journalism. He still finds time to recreate his dreams of stardom in his pop-punk tribute band, Finding Emo.

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83