Why 2020 marks a new golden age for Fender

How the world’s biggest guitar company takes the guitar world’s most-loved instruments and remakes them anew

70 years have passed since Fender launched its first solid-body electric. A slab of pine with a solitary single-coil pickup appropriated from a lap steel, the Esquire showcased an adjustable three-saddle bridge, a bolt-on maple neck and a very appealing shape...

In short order, via two quick evolutionary and appellative leaps, the Esquire became the Telecaster, and the rest is Fender history. But history has weight. Music, and popular culture as a whole, is governed by a nostalgia that can be gravitational, pulling anyone who thinks outside the box back to earth. It is no different for Fender.

How Fender deals with this – the idea that says the best guitars have already been made – is instructive for anyone interested in guitar culture.

A lot of other people would have designed the Esquire and thought that was good enough

Maybe the answer is right there in front of us, the clues to be found in the guitar store and online; it is the guitars, amps and effects that show us how Fender placates vintage purist and neophyte alike.

Such an approach won’t work for all guitar companies. Each brand has its own pressures and expectations – to thine own self be true. But as Justin Norvell, Executive Vice President, Fender Products, explains, Fender’s evolution is one that can be shepherded along by using its design language and the vast vocabulary of spec at its disposal, paying dues to the past where appropriate.

Maybe you’ve got to know where you have come from to know where you are going...

Of all the modern inventions, the electric guitar is unique. Like the television set or telephone, it too has evolved out of sight, incorporating new technologies, different builds, assuming new shapes, and yet many of the electric guitar’s earliest designs are still considered the gold standard.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

There is a sense that they pretty much got ‘em right the first time around. Where does that leave a company such as Fender? Well, you keep at it. As Justin Norvell reminds us, respecting heritage and pushing design forward might be a “delicate dance”, but its evolution was how Leo Fender built the company. ”

Going back to Leo’s earliest days, nothing is sacred. You can just try another model, try another set of pickups, wire it differently, change the neck shape. The history itself doesn’t put you in a box

Justin Norvell

“I think a lot of other people would have designed the Esquire and thought that was good enough, and it wouldn’t have become the Broadcaster/Nocaster/Telecaster,” says Norvell. “A Strat in ’54 was ash-bodied, U [profile] neck, and it changes, so by ’57 it is V neck and alder body, and then the rosewood fretboard comes in, and then everything keeps evolving.

“It has always been changing. Going back to Leo’s earliest days, nothing is sacred. You can just try another model, try another set of pickups, wire it differently, change the neck shape. The history itself doesn’t put you in a box.

When we look at Fender’s 2020 line-up, it is the product of a Janus-faced evolution.

Series such as the Mexican-built Vintera and the US-built American Original face backwards, strip-mining Leo’s old notebooks to offer guitars that place Fender’s history front and centre. Fender’s entry-level brand, Squier, does something similar with the Classic Vibe models.

Fender’s pedal game has impeccable under Stan Cotey’s watch. Anodized aluminum enclosures, with switchable LED knobs, magnetically-latched battery doors and – chef’s kiss! – a Fender jewel power light... Lovely!

Check out the Tre-Verb as an alternative to the Strymon Flint, or the Compugilist for a very useful compressor/distortion.

Then you have the contemporary, affordable Player Series, the workhorse American Professional models, each pointing ahead to the forward-facing American Ultra series, home to Fender’s flagship US production line models, and the Acoustasonic Series, which takes the Telecaster and a Stratocaster and makes multi-voiced electric-acoustic hybrids of them.

When the American Ultra series was ushered in, it was the textbook example of how Fender refreshes its top-line instruments.

Across the range, the ‘Modern D’ neck profile was rolled out, with compound 10-14-inch radius fingerboards, newly wound Ultra Noiseless pickups, a gold-foil Fender headstock logo, revised body contouring, locking tuners and an eye-popping complement of new finishes.

It is guitar-making as showing off, with Texas Tea and Mocha Burst up there with Surf Green and Fiesta Red among Fender’s finest finishes.

The Acoustasonic is Fender through the looking glass, but it is funny how, 18 months on, we have absorbed the shock of the new, with the hybrid format delivering something that we never knew we wanted in the first place.

There is something sacred about the design language and the tonality in the sound

Justin Norvell

Maybe it’s precisely because the Fender thumbprint is all over such an avant-garde guitar design is what inspired our initial bemusement, then acceptance. If so, it’s deliberate on Fender’s part.

“There is something sacred about the design language and the tonality in the sound,” says Norvell. “We really branched out and expanded the roster, but in a tasteful way, and in a very Fender way, adhering to some of those design elements and cues, where you can bring something new to the market but also something that feels [right].”

The Acoustasonic is not the sort of guitar Fender would have made 20 years ago. It took partnering with Fishman to develop the guitar’s acoustic engine to make it sonically viable, to make a tool of it. Very Fender. After all, Leo’s brand of genius was strictly utilitarian.

Some of Fender’s contemporary designs require new tech to breathe life into them. Others, such as the Paranormal and Parallel Universe series, the latter in its second generation, require new thinking, and the spirit of Victor Frankenstein at the workbench.

Consider the Parallel Universe Volume II Maverick Dorado. A heavily contoured offset with a Bigsby, and Tim Shaw-designed humbuckers hiding under Filter’tron pickup covers, it’s like a Jazzmaster designed by committee – using leftovers. That hockey-stick headstock? The neck is from an Electric XII.

“It’s really an area to not take ourselves as seriously and also to be a little more edgy, experiment, and offer something different,” says Norvell.

Some of the more outré designs hark back to the 60s and 70s, when there was a growing radicalism in guitar design. The 70s CBS-era saw Fender’s reach oft-exceed its grasp, leaving forgotten models ripe for rediscovery.

“That hasn’t been historically the brightest time in Fender’s history, but there is a lot of odd stuff like the Swinger, the Bronco, the Starcaster, the Maverick,” says Norvell. “They were just trying to mash up different pieces of different instruments to see what worked.”

A semi-hollow offset, now built under the Squier name with three versions to choose from, the Starcaster is proof that odd works, only sometimes it has to wait its turn.

It’s tempting to interpret the Parallel Universe models as test balloons for new series. Each is deserving of an essay in its own right.

The Mágico started off as a Custom Shop one-off that Ron Thorn did. Ideas can come from anywhere

Justin Norvell

Norvell describes them as testing grounds for spec, citing the Telecaster Mágico as case in point, with its gold-foil pickups and ‘cut Telecaster’ bridge, sporting three compensated brass saddles to offer a similar look to vintage three-saddle Tele bridges but with improved intonation.

“The Mágico started off as a Custom Shop one-off that Ron Thorn did,” says Norvell. “Ideas can come from anywhere.” Oftentimes, that ‘anywhere’ is the artists. The signature guitars of Fender’s Custom Shop and Artist Series are designed in collaboration.

Among the current signature lineup are two Jim Root Jazzmasters, a Tom Morello Stratocaster, a very cool 60s-style Tim Armstrong Hellcat electro-acoustic, Teles for Brad Paisley, Brent Mason, Britt Daniel, and some guy named Jimmy Page.

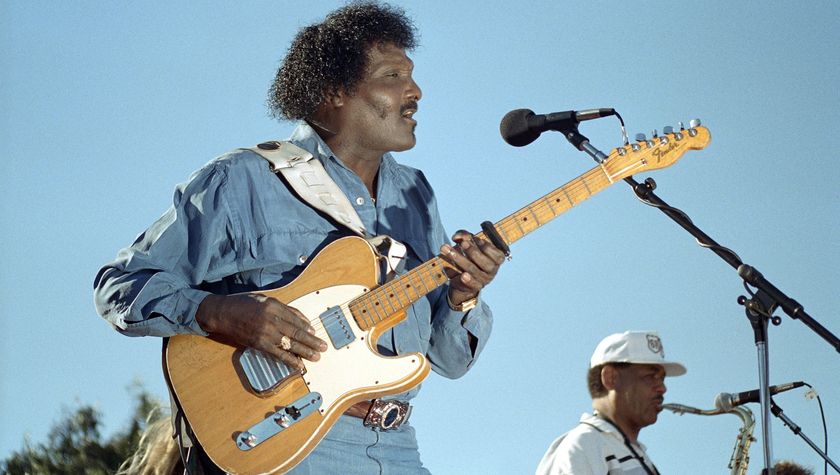

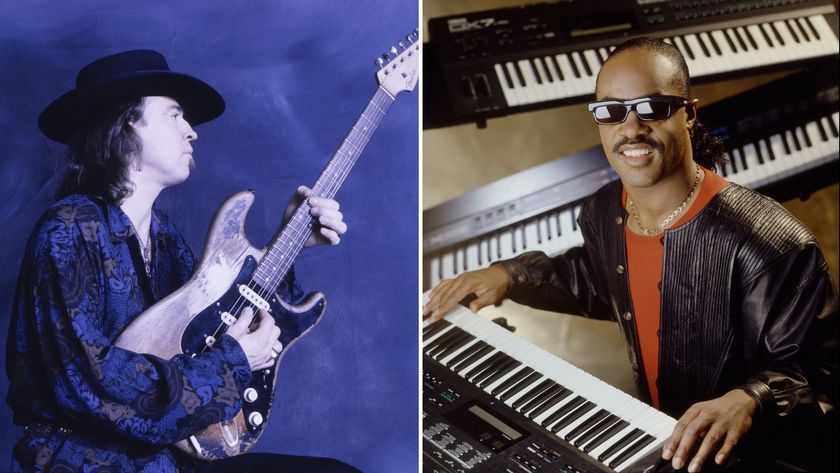

The list goes on. The are Strats for Buddy Guy, Eric Johnson, and Kenny Wayne Shepherd. Each brings something different to the table.

Shepherd’s Strat is fresh out the shop. It has a chambered ash body with a Transparent Faded Sonic Blue finish, a four-ply pearloid pickguard matching the fretboard’s block inlay, newly voiced pickups, and reverts to a 7.25-inch radius fretboard. It’s a Shep Strat dressed in a Tux.

“I wanted this guitar to have its own identity,” says Shepherd. “Just because my last signature guitar had a 12-inch radius does not mean that is the only way I like to play guitar.

Fender’s amp development has mirrored that of the guitars. There are the vintage reissues of the Princeton Reverb, Deluxe Reverb and the Twin Reverb – the perennial valve-combos in the line.

But with the Mustang and Tone Master series, Fender has embraced amp modelling tech, the Mustang’s offering onboard effects, digital connectivity and a options for the domestic shredder.

The Tone Master series, meanwhile, offers uncanny modelling replicas of the Deluxe and Twin. In a blind taste test, you’d do well to sort valves from digital processor. Lift them up, though, and the Tone Masters are super-light. And that’s progress.

“This neck is a much more true example of what I have been playing onstage whenever I pick up any of my Custom Shop Strats, and the goal was to try and get as close as possible to the feel of the neck on my ’61 Strat which, to me, is the best feeling Stratocaster neck out of all the guitars that I own.”

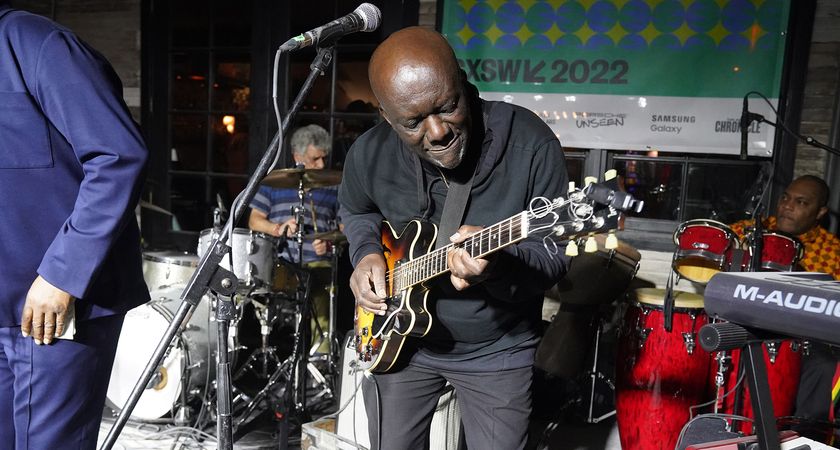

Even without their name on the headstock, artists influence design. In 2020, the age of the offset, it feels like we’re cresting a wave that started in the late 80s gathering steam through the 90s, when the likes of Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr. and Nirvana picked up Jazzmasters and Jaguars because they were cheap, odd and dispensable. What was designed for a sit-down jazz session was tossed around and scarred by a new generation of punk rock.

As a child of the 80s, Norvell acknowledges the feedback loop, and the internet-driven aftermarket that accelerated the offset’s resurgence. “A whole industry popped up around them,” he says. “Buzz Stops and different bridges, different tremolos.

Those guitars were so modifiable because they were so inexpensive.” Norvell sees it as a form of crowdsourcing. “Fender has always been about constant feedback from players and artists, and that continues to this day.” But what till tomorrow bring? Norvell says it will follow the music.

With services such as Fender Play complementing a wide variety of entry-level guitars with learning materials, he sees Fender’s job as creating paths for guitar players, but especially beginners.

“Everybody thinks the guitar is cool. Everybody wishes they played. But there’s always some excuse or reason why they never did. We just want to lower all of those barriers. I mean, if you get bitten by the guitar bug it is consuming, and so fulfilling.”

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

One of the UK’s biggest music retailers takes website offline and shuts store for “maintenance”, fueling closure speculation

“If fashion brands and computer brands can do it, why can’t we?” I journeyed to the only dedicated Fender store in the world – and found out how it could change the future of guitar retail as we know it

![[L-R] George Harrison, Aashish Khan and John Barham collaborate in the studio](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VANJajEM56nLiJATg4P5Po-840-80.jpg)