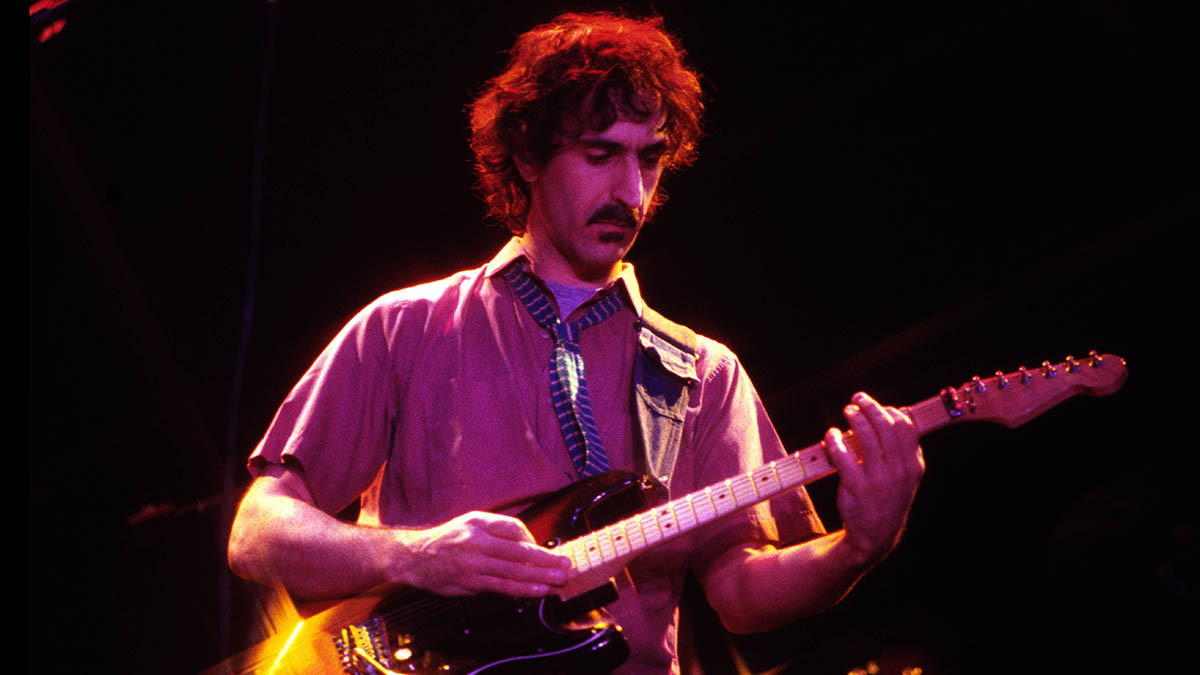

The opening frame of Alex Winter’s 2020 intimate-portrait “biopic” documentary, Zappa, shows Frank Zappa onstage at the Sports Hall in Prague, Czech Republic, in 1991 holding the Stratocaster you see on the cover of The Guitar World According to Frank Zappa, a 34-minute collection of rare Zappa solos on an audio cassette that Guitar World released in 1987.

“This is the first time I’ve had a reason to play my guitar in three years – and now I will try and tune my guitar,” he says. It was to be his penultimate recorded guitar performance. (The Prague date was June 24, 1991, followed by his performance in Budapest at the “Farewell Festival,” celebrating the withdrawal of Russian troops from Hungary, June 30, 1991.)

In fact, it was several years before that – in October 1986 – that I interviewed Zappa at his Laurel Canyon Fortress of Solitude, later occupied by Lady Gaga and sold just before we went to press, to plan out the tracks of that very same Guitar World cassette – and talk about guitar stuff. [A vinyl edition of the album was re-released on Record Store Day, April 13, 2019.]

As we – GW associate publisher Greg Di Benedetto and I – descended with Frank into the bowels of his private inferno, otherwise known as the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (U.M.R.K.), he told me with a straight face that he hadn’t played serious guitar in two years and that he’d even lost his calluses.

After viewing the documentary, I put on my Sherlock Holmes hat and weighed his statement about giving up on the guitar back in ’84 against his liner note on the cassette about the song A Solo from Atlanta, recorded live in autumn 1984: “There weren’t very many people at this concert. Too bad they missed it. This was toward the end of the 1984 tour. The last concert of the tour was the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles, December 23. I haven’t played the guitar at all since then.”

So... with the benefit of hindsight, having watched the Zappa documentary, am I to deduce that Frank missed his beloved ax so much that he picked it up again in 1991, practiced with it, jammed enough to build up his calluses to the point where he could regale the Czech faithful one last time with his finger-lickin’-good chops on that Strat before shedding his mortal coil to join Jimi, Janis and Johnny “Guitar” Watson in that great jam session in the sky?

Yes, he did. Because even though he denied it, Frank loved the guitar, and the image of him with that Les Paul with the cigarette always stuck in the nut endures.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

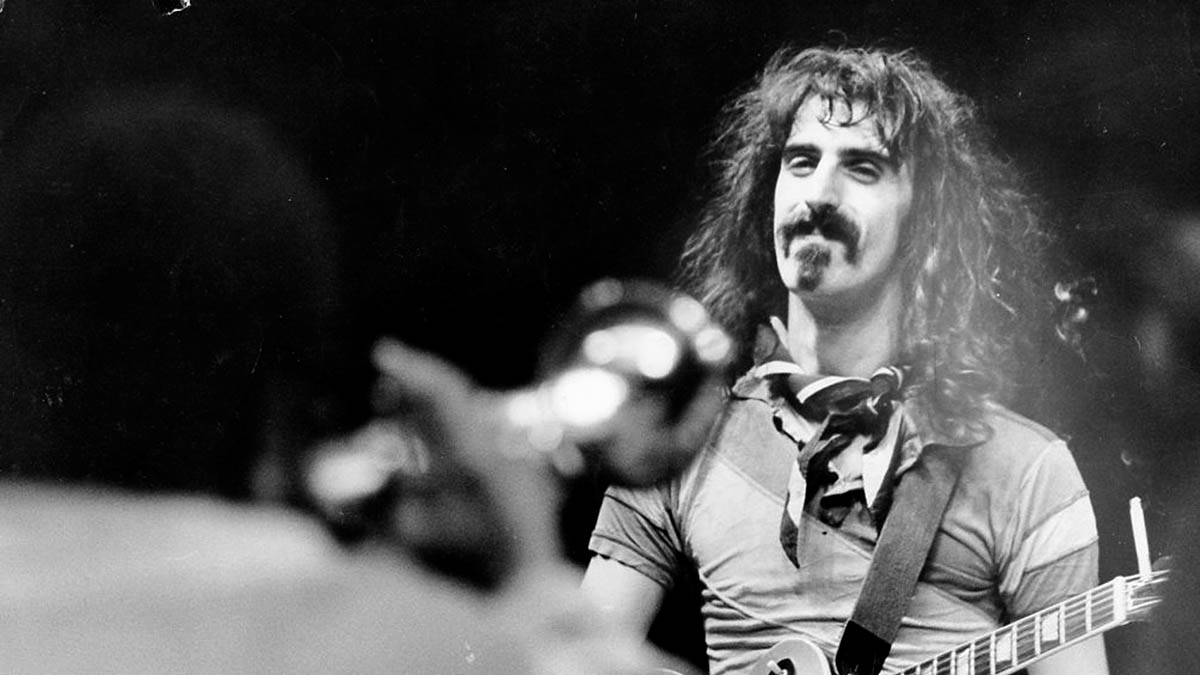

“Once I figured out that the pitch changed once you put your fingers down on the fretboard, I was hell on wheels,” he says in the film. Whether he acknowledged it or not, Zappa had been admired by guitarists for years because of the sheer free-flying gonzo-ness of his solos within the otherwise-precise organization of his compositions.

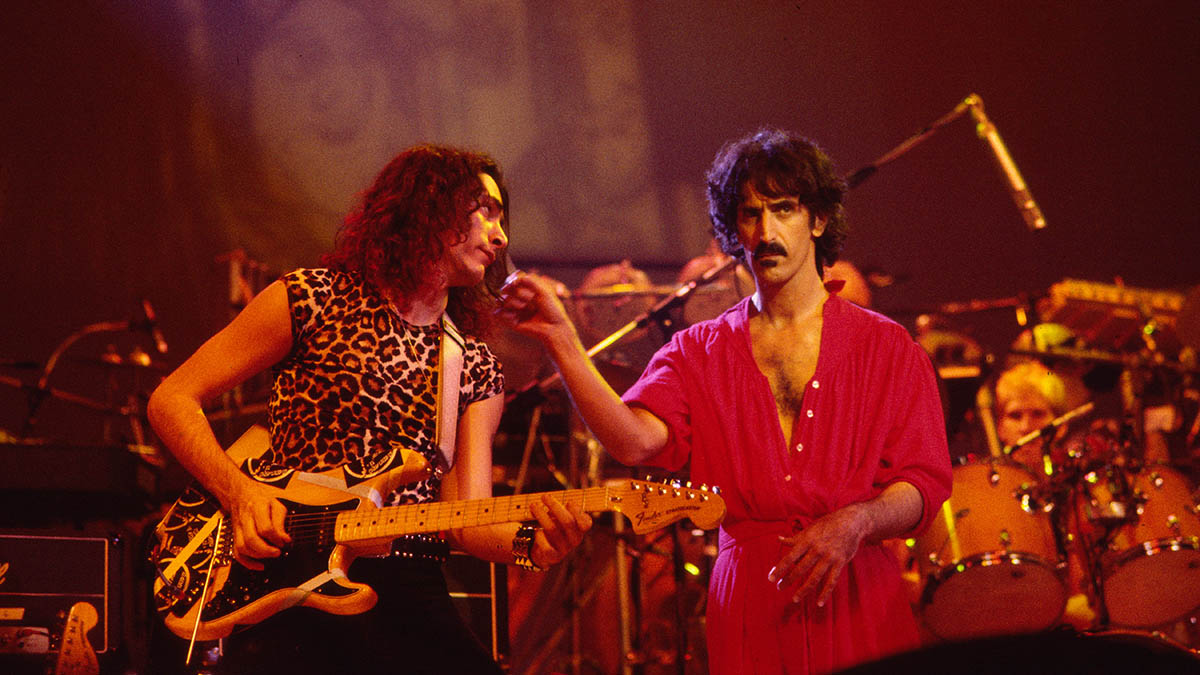

He was always a real Mother of a player. As a bandleader, his insistence on perfection brought out the best in his players, especially the guitarists he introduced to the world through his succession of bands; Lowell George, Adrian Belew, Warren Cuccurullo and Steve Vai all cut their teeth in Zappa’s marching society.

I asked Frank about some of his protégés. “Steve Vai, for instance. Does he keep in touch with you?”

“Yeah, he comes over every once in a while.”

“How did you first meet up with him?”

“He sent me a cassette when he was 17, a student at Berklee.”

Steve Vai sums it up about FZ’s bandleader profundity in the film: “My perspective of it is when I was in it I was a tool for the composer. Whatever is in there, he uses as he deems fit. Zappa was draconian and he saw us as components in his master plan.”

A couple of years later, Vai went down to a rehearsal studio to audition. “When I went down there, he was brutal on me. I’m 20 and green and eager. He would play something on guitar and then he would say, ‘Now play it in 7/8,’ and I do it and then he says, ‘OK, now play it reggae style 7/8,’ and I do that and he says, ‘OK, now add this note... and that was impossible, not just for me but for anybody.

“So I go, ‘I can’t do that.’ He goes [Laughs], ‘I hear Linda Ronstadt is looking for a guitar player.’

“So at the end of the rehearsal I go up to him and I say, thanks for the opportunity. I’m really sorry, I’m gonna go home now. He goes, ‘You’re in the band.’ And I hugged him. He was always cool, he was always great. I think the definition of a genius is somebody that can call into play – organically – this inspiration anytime they want, and I’ve seen Frank do this over and over again. This one time, Halloween at the Palladium in New York, Frank just played the guitar like I’ve never seen anybody in my life.”

Steve is referring to the last song of that set, a cosmic rendition of Black Napkins. I can testify to that because I was there; photographer John Livzey and I have the backstage pass to prove it. I just rewatched it on YouTube and my head is still spinning from his absolute joy of playing the guitar.

“He knew how to get the best out of people. In my case, I would test myself with things that seemed impossible to play, but which he knew I could do. He could get things from me that were unimaginable if he had not thought of them,” Vai says. “And that gave me confidence, because he was not going to ask for something I could not do well.”

Eddie came by to visit every now and then. He made a huge difference to my brother; that’s how I got into Van Halen – through Dweezil’s unholy fascination with that mighty group. Eddie and Frank were friendly

Ahmet Zappa

I have always been an FOZ – Friend of Zappa. In my Guitar World days, I hung out with Dweezil as we rode around L.A.; I accompanied Gail Zappa and her kids one memorable night in Trancas when we saw a performance by Van Halen at a little club in the hills above Malibu; and later, as the managing editor of VJ scripts and news segments at VH1, I worked with Moon in New York.

And John Livzey, my friend who joined me in a recent interview of Ahmet Zappa and Alex Winter, was Frank’s go-to photographer for album covers and shoots on-stage and off.

First the introductions.

“My name is Noë Gold, founding editor of Guitar World. My story with Frank goes back to the ’60s, when I got an assignment to go to the East Village and cover this band called the Mothers of Invention. A little bit later in my career I got to do the liner notes/press package for Over-Nite Sensation. Later on when I was with Guitar World I got to come out to L.A. and sit down with Frank to talk about guitars.”

AHMET ZAPPA: “Awesome, a ton of awesomeness. All I got is, he was my dad.”

Zappa represented to my group not only a masterful musician but an artist who had a razor-sharp wit and a very astute political mind

Alex Winter

ALEX WINTER: “My journey began in the ’70s growing up with a musician brother and a predilection for cultural personalities like Zappa’s who were engaged with their art but equally engaged with the times around them. Zappa represented to my group not only a masterful musician but an artist who had a razor-sharp wit and a very astute political mind.

“So he took a bigger place in our minds than these guitar heroes, what they could actually be. I always felt his story was so compelling outside of his musical journey. He seemed like a ripe character for a documentary.”

Gail Zappa made Winter’s wish come true six years ago, when she gave him full access to the very same vaults I visited.

JOHN LIVZEY: “Ahmet, the period that the film traverses, I believe you were around 5 or 6. Your dad came to my studio only once in ’81 before they went on the European tour kicked off by the Halloween show. The all-night session that wound up being a cover shoot for Shut Up ’n Play Yer Guitar, that was in the Laurel Canyon house. I came up about midnight and I was there till about 4. We had a good time.”

AHMET ZAPPA: “How many beers and how many packs of cigarettes did you go through?”

JOHN LIVZEY: “There weren’t any beers, but he had plenty of cigarettes and plenty of coffee. He had that coffee-plunger thing. He loved coffee.”

AHMET ZAPPA: “Tell me about it... that was my first job, making coffee.”

“I am interested in the guitar aspect,” I countered. “Did you have any discussions with people like Steve Vai about the guitar? The Strat that belonged to Jimi?”

“You can’t talk about FZ without talking about the guitar,” Ahmet says. “We’re always discovering great new music with blistering guitar solos. There will be future releases where he plays that guitar. Eddie came by to visit every now and then. He made a huge difference to my brother; that’s how I got into Van Halen – through Dweezil’s unholy fascination with that mighty group. Eddie and Frank were friendly.”

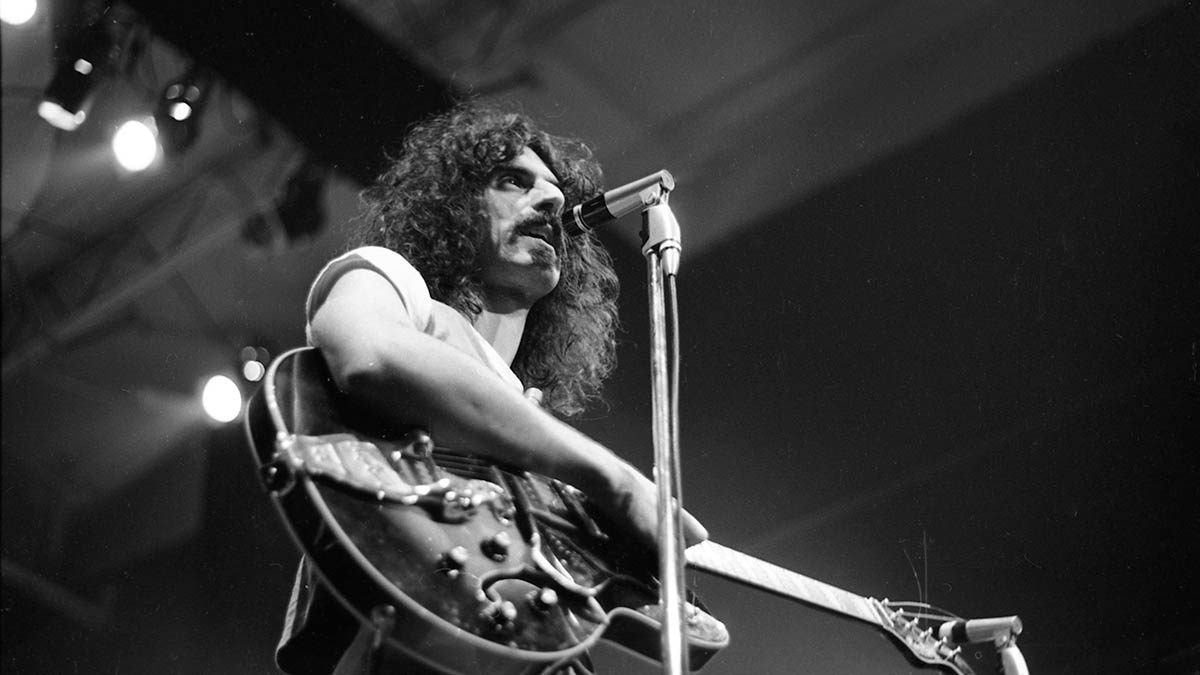

Flash back to my interview with Frank. I opened the conversation with: “Do you see a conceptual continuum between Call Any Vegetable and Shut Up ’n Play Yer Guitar? Or between the Mothers of Invention and The Mothers of Prevention?” – which I thought would open him up to some disquisition about needling versus noodling.

His response: “There are some links, yeah. The main drawback of the medium I’m working in is, until I got the computer, I was locked into making music based on the assets and/or liabilities of the guys in the band. In other words, if you want to write something that’s faster than what the guys can play, you can’t hear it, because they can’t play it that fast. But now that I can do it with a computer, that’s not a problem anymore.”

In other words, the master was doing a lot of tapping, but not on any guitar neck. With the synclavier, his new-found instrument of choice, he said, “I can enter information with the octapad; you can take a completely improvised line and build an entire composition out of it.

“You see, it’s still a single line. But with this, you can improvise a single line and have that line being played by a whole ensemble of instruments and actually have those instruments play that line in harmony.”

“What is all that activity doing to your guitar playing, per se?” I asked.

“Haven’t touched it in two years. I don’t even have the calluses on my fingertips.”

When you see what the guitar solo has been reduced to in contemporary music, it’s like an eight-bar fill... you’re supposed to play every hammer-on lick that you know as fast as you can play it, followed by 15 feedback noises and then get the fuck out

Frank Zappa

There was a brief pause as the interviewers collected what was left of their minds from the floor. Then he took us down into the vaults, the vast collection of tapes, reels and canisters filled with every single piece of music he had ever created.

“Here’s Eric Clapton when he came over to my house,” he said. And as to the reams of tape with blistering solos we were digging through in those vaults, since they seemed to be popular, he fully intended to release them over time – which the family has done faithfully over the years. And the guitar solos that punctuated his best work?

“Well, look at it this way: I got plenty of tapes of these things. I can release another guitar solo album. And, when you see what the guitar solo has been reduced to in contemporary music, it’s like an eight-bar fill. And during that fill, you’re supposed to play every hammer-on lick that you know as fast as you can play it, followed by 15 feedback noises and then get the fuck out of there. You know, that’s what the guitar solo has been reduced to, and that’s not the medium I’ve ever worked in.”

“But the actual playing – you don’t miss it at all? Because I – and a lot of our readers – love your guitar sound. To me that always meant your personal voice within whatever music we were hearing. When you hit the guitar solo, it was not precise at all. It was something transcendent, something out.”

Most of the best stuff I will physically be able to do on the guitar is already on tape. You just haven’t heard it yet

Frank Zappa

“Every once in a while, I miss it,” he says, noting again that he’s lost the blisters on his fingers. [Zappa sits back in his chair, letting this one sink in.] But I don’t play a style that is contemporary, you know? I don’t do all the 1980s guitar noises. If you don’t sound like Eddie Van Halen, then apparently you don’t actually play guitar anymore – the current audience would listen to it and go, ‘That’s not a guitar. It doesn’t go ‘wee wee wee wee, wee wee wee wee.’ So why do it?”

“Dweezil would probably rebut that,” I say, “what with his own infatuation for Eddie Van Halen – and he is on MTV.”

“Well, I can’t help the way he looks. And he chooses his own wardrobe, but the fact of the matter is that Dweezil can actually play an instrument.”

“So that’s a fluke, according to your theory of how musicians make it these days.”

“Yeah, yeah. Uh, he’s a mutation. I’m not saying anything against Eddie because I think what he’s done for the guitar is wonderful. But the thing that’s tragic about the marketplace is that everybody decided that they were all going to do that, and then the competition is not musical.

“It’s gymnastic. Okay, they say, ‘I want to sound like Eddie, but in order to be better than Eddie I have to be faster than Eddie.’ Meanwhile, Edward probably sits back and goes, ‘These guys are really stupid.’ Because I don’t think that’s what he had in mind when he developed the style.

“The problem is, most of the best stuff I will physically be able to do on the guitar is already on tape. You just haven’t heard it yet. I mean, I don’t have much incentive to play it. I can still think guitar. But to physically manipulate it, I would have to go back in and woodshed for months on end just to be able to do it. Dweezil practices non-stop, day in, day out,” he says.

“I recall you saying once that the hardest thing to accomplish in a guitar solo is to come up with a distinct melody within that solo. When you’re working with the Synclavier, and you get to a point where in the old days you were thinking about composing for the guitar as well, what do you do at that juncture? Do you put a coda-type thing in there?”

“It would be difficult to talk about what I’m doing over there since you don’t know what it is. I should just stop the tape and go over there and show you what I’m doing.”

[Stops tape and we get a demo of Frank composing on the Synclavier. He taps out a few seemingly random rhythms, makes some observations of the CRT screen and manipulates parameters of music around the “random rhythms”. The music coming out of the Synclavier is many-faceted, but typical Zappa, with percussive, marimba-esque runs and odd cat growls prancing about together.]

“That sounds like your music. Same guy.”

“Are you familiar with the piece on the Shut Up ’n Play Yer Guitar album called While You Were Out?’” he says. “Well, on the new album [Jazz from Hell, 1986] there’s a deluxe computer version of that [While You Were Art II]. But it’s not played by a guitar. I look at that thing – the recording console – and it’s like a musical instrument, if you use it the right way. You’ve gotta start with a musical idea. if it’s not a musical idea, what is it? An equation?”

“How do you get that? How do you start? Do you have entire complicated things full-blown that spring out of your brain, or do you start with something small and you build it up?”

“Sometimes I have a complete vision of what the thing is, and it’s just drudgery to go in there and execute the vision, and if you like it you save ’em and make a piece on it, and if you don’t you throw it away.”

Again, the interviewers have to pick up their splattered brains from the floor. “How do you keep track of everything? On each floppy, there’s like a million things –”

“Aaah! Then you have to have a good memory.”

“Yet, when we first started talking, we discussed guitar noisemakers and these devices that you seem to have a fondness for – the Green Ringers and the Uni-Vibes and such. Things that give that idiosyncratic, anarchic tone.”

“Well, I like the sound of a guitar. My idea of the best use of a guitar is something that’s personal... not necessarily commercially viable. There are things I like to hear coming out of a guitar. But that’s my personal taste.”

“The Shut Up ’n Play Yer Guitar series. How did the three records do commercially?”

“Real good, as a matter of fact,” he counters. “And it surprised the shit out of a lot of people. When it was first released, there were 30,000 units of that three-record box sold in France alone. It’s done well and it’s still selling.”

One thing I always hated to do was play guitar in a studio. I always thought it was an incredibly boring experience. Like playing in a vacuum, isn’t it? So therefore, in order to really play guitar, you’ve got to hire a band, and that becomes cumbersome

Frank Zappa

Again, I ask him about getting out of the house. “Do you have any urge to play at all in public anymore?”

“I’d have to have an awful good reason, and in order to play in public I’d have to learn how to play the guitar again – literally. I couldn’t bend the strings.”

“It’s weird because we’re from a guitar magazine and you’re not really into playing guitar anymore.”

“What’s that got to do with releasing guitar records? As I told you, there’s plenty of stuff on tape. I can play you some stuff – examples of what’s lurking in the archives. One thing I always hated to do was play guitar in a studio. I always thought it was an incredibly boring experience.

“Like playing in a vacuum, isn’t it? So therefore, in order to really play guitar, you’ve got to hire a band, and that becomes cumbersome. And I guess nobody’s going to want to audition just to be in Frank’s backup band, just so Frank can play guitar. If it’s not necessarily going to go on a record or something. It’s the law of supply and demand, you know? There ya go.”

And that is how I wound up working with Frank Zappa on The Guitar World According to Frank Zappa.

- Adapted from Conversations with Rock Stars, coming soon from a major publisher.

Noë Gold was the founding Editor-in-Chief of Guitar World magazine.

“There’d been three-minute solos, which were just ridiculous – and knackering to play live!” Stoner-doom merchants Sergeant Thunderhoof may have toned down the self-indulgence, but their 10-minute epics still get medieval on your eardrums

“There’s a slight latency in there. You can’t be super-accurate”: Yngwie Malmsteen names the guitar picks that don’t work for shred

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)