Warren DeMartini on the ‘80s: “Everybody wanted to play like Eddie, and every band wanted to hit it big like Van Halen”

Nineteen-year-old Warren DeMartini made the move from San Diego to Los Angeles in 1982 just as the Sunset Strip glam metal scene was on the cusp of exploding nationwide. For a young hotshot guitarist looking to get noticed, L.A. in the early Eighties was like a mecca.

There were clubs teeming with women and A&R scouts. There were parties and strip joints. And there were thousands of other like-minded budding shredders hoping to be the next Eddie Van Halen.

“Back then, Eddie was sort of the apex of a new direction for guitarists of my generation,” DeMartini remembers. “If you were just getting in the game like me, he was the guy to look up to. He made it all seem so exciting. Everybody wanted to play like him, and every band wanted to hit it big like Van Halen.”

While most of his six-string peers hustled for gigs, putting up flyers and advertising their services in local musician’s papers, DeMartini arrived in L.A. with something of an ace up his sleeve: He had already accepted an invitation to join the up-and-coming outfit Ratt, replacing his friend Jake E. Lee, who had signed on with Ozzy Osbourne following Randy Rhoads’ passing.

For the next few months, Ratt played every gig that came their way, soon becoming the house band at Gazzari’s, the same club where Van Halen got their start.

“The competition was fierce, but it was also healthy,” DeMartini says. “I thought the whole thing was fun, and I really loved performing. There were a lot of things that could break your competition, but I didn’t let anything get in the way. I kind of kept my head down and worked on music. I just wanted to play guitar as best I could and learn to write songs.”

Ratt (which also included singer Stephen Pearcy, rhythm guitarist Robbin Crosby, bassist Juan Croucier and drummer Bobby Blotzer) made a sizable splash with the release of their self-titled 1983 EP, and a year later they hit triple platinum with Out of the Cellar, which featured the smart-alecky pop metal smash Round and Round (written by DeMartini, Pearcy and Crosby).

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Halfway through Van Halen’s set, I realized I left my jacket on the stage, right behind the PA speakers on Ed’s side. My keys were in the jacket, and losing them wasn’t an option. So I went for it...

Throughout the decade and into early Nineties, DeMartini’s energetic and snaky solos – a deft mix of fluid legato lines, spunky whammy bolts and a sinuous vibrato – highlighted a number of memorable hits that saw the band graduate to arena headliners before a combination of internal squabbles, substance abuse and the rise of alternative rock stopped them in their tracks in 1992.

Since that time, there have been a number of Ratt reunions, some involving DeMartini but none comprising what is regarded as the “classic” lineup (Crosby passed away from a heroin overdose in 2002).

The subject is a thorny one for the guitarist – there have been numerous lawsuits between members as to ownership of the band’s name – but in the following interview he looks back at his time in the Ratt race.

You mentioned Eddie Van Halen as being the top guy for guitarists when you were coming up. How much impact did he have on your playing?

“Oh, a lot, sure. There was his sound, but there was also his whole style. He had a shuffle that nobody else had. I was crazy about that shuffle in I’m the One. I think Eddie got some of that from listening to Eric Clapton, although he played much slower. There was the same kind of snappiness, though.

“Kind of a funny story about Eddie: Robbin knew him a bit, and I think he also knew some people on Van Halen’s crew, so we got passes to the band’s show in San Diego during the Women and Children First tour. I drove us there, and we got to the arena before the opening act went on. A crew guy that Robbin knew showed us Ed’s rig, and we talked for a bit.

“A while later, halfway through Van Halen’s set, I realized I left my jacket on the stage where we were talking, right behind the PA speakers on Ed’s side. My keys were in the jacket, and losing them wasn’t an option. My pass got me backstage again, so I climbed the stairs to the stage level and saw my jacket 20 feet away.

Nobody was looking, so I went for it – halfway to my jacket, I paused and took in the view from Ed’s world. The band was surrounded by the sold-out arena. Then Ed started moving to his left, and for a few moments his spotlight hit the two of us. Right when the monitor guy noticed me, I took a few more steps, grabbed my jacket and booked.”

Wow, that’s a great story.

“Yeah, that was as scary as it was exciting. My first view to the stage! [Laughs]”

People often cite your vibrato. How did you start to develop your technique?

“From Jake E. Lee. I went over to his house, and it was the first time I saw somebody really play that way up close. I was pretty mystified about how to use vibrato, and Jake told me that I had to start slow and then go wide. After that, you don’t have to think about it anymore. That was one of the few times I got advice from somebody and was able to put it to good use.”

You replaced Jake in Ratt. What was the band like with him?

“They were great – really great, in fact. Good songs, and Jake was killer. I think there might be cassettes of their rehearsals floating around out there, but I don’t know about any videos.”

When you joined Ratt, did you and Robbin Crosby hit it off right away?

“Oh yeah. I was friends with Robbin before he knew any of those guys. He and I went to the same junior high school – not at the same time, but we lived in the same area. I was interested in the guitar, and he was already in a band that played all the time. So when I first got into the guitar, he was out of high school and living the life. His band played covers, but they did some originals, too.

Did it take a while for you two to mesh as guitarists?

“It was pretty easy, actually. I got turned onto a lot of cool stuff because of him – he always knew the stuff that wasn’t being played on the radio. Playlists in San Diego at that time could be on the conservative side, but Robbin was listening to Pat Travers, Scorpions with Uli Roth, UFO – and way before they got on the air. We had a great time listening to that stuff together.

Lead guitarists usually get more of the attention from the press. Do you think Robbin ever minded the spotlight falling more on you?

“If he did, he didn’t mention it. I mean, he never said anything like that. And you know, I didn’t think about that sort of thing. I was just very focused on making my own contribution to the band and doing the best I could with the time I had.”

One of your first compositions for Ratt was Round and Round. Did you originate the song?

“After high school, I moved to L.A. in a Fiat piece of shit, and about all I had was a guitar, a Marshall stack and a little tape recorder. On that recorder was Round and Round in its earliest form. I’d been working on it for a long time, just crafting it.

“I remember thinking, ‘How do you even write songs?’ I kept trying to come up with parts and then make them all fit together. About a year later, Robbin, Stephen and I completed the song one afternoon in a small apartment we shared in North Culver City.”

Robbin and I drove out to Charvel, and Grover said, ‘You guys are obviously Charvel fans. I’ll build you the best guitars I can, and we’ll work something out later when you can afford it’

You seemed to have figured out songwriting quickly. You were also a writer on Lay It Down, Dance and Way Cool Jr. Did the band kind of look to you for hits?

“I don’t know. I think the tendency back then was to think your stuff was going to do well. Everyone’s ideas got worked up, but not every song got recorded. We had to narrow it down to ten tracks because at that time we only got paid on ten songs per album. We did the best we could, and then you’d get word from the label [about] what’s going to be a single. There was a pattern that the stuff I brought to the group was on that list.”

Your solos were always very memorable. Did you demo them as you wrote, or were they off the cuff?

“Both. Back then, we’d record basic tracks with maybe a scratch vocal, but a lot of times you wouldn’t get the kind of guitar sound you wanted to commit to record. After we’d get most everything down, I’d go back and work on the guitar sound. I’d refine ideas.”

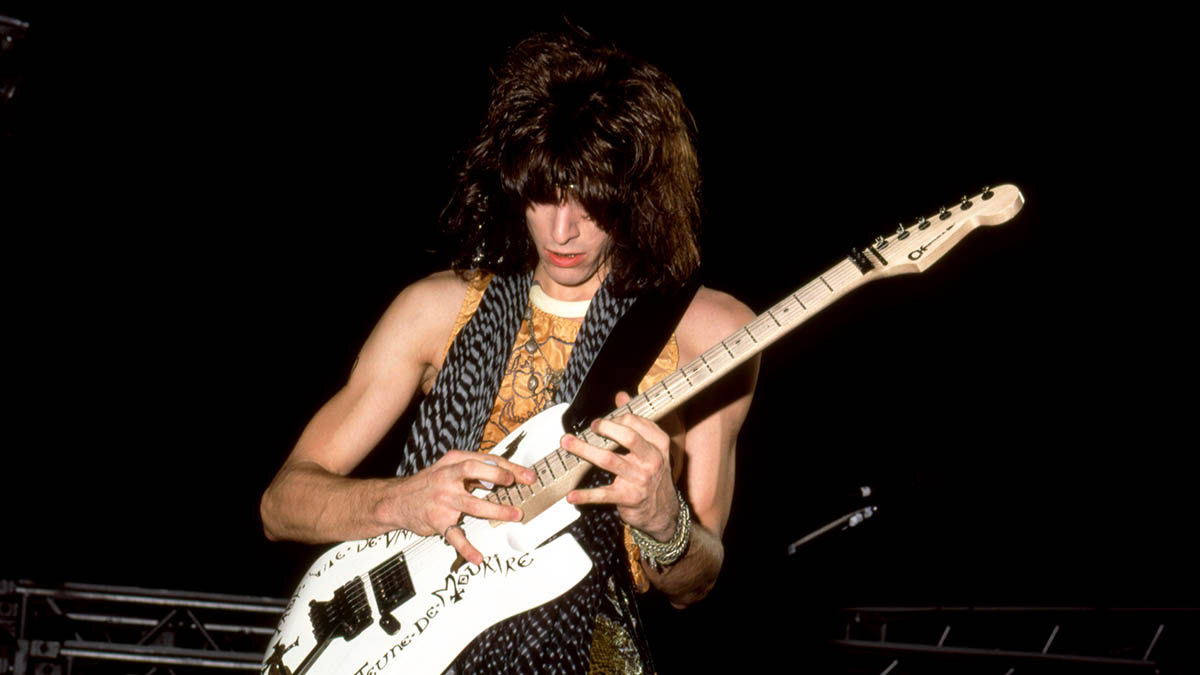

You were playing Charvel guitars pretty exclusively at the time.

“Right. That started because of those first two Van Halen records. The first Van Halen album was a Boogie Body, but the second one was clearly a Charvel. That was part of the revolution Ed started, where you could put together your own guitar.

“A friend of ours happened to get a job at Charvel, and for a little while we could buy guitars and necks that were seconds – the stuff Grover wanted to throw away. You could get a guitar or a neck for cheap, so that’s what I did; then I’d buy hardware and pickups and that kind of thing.

“Skip ahead a few years and I got a message from a friend who was a graphic artist at Charvel: ‘Grover Jackson wants to see you. I immediately thought, ‘Oh, man, he wants me to rat out whoever was selling me these seconds.’

“Robbin and I drove out to Charvel, and Grover said, ‘You guys are obviously Charvel fans. I’ll build you the best guitars I can, and we’ll work something out later when you can afford it.’ Which was awesome. That’s right around the time when the ‘crossed swords’ guitar was built.”

Ratt broke up in 1992 but regrouped a short time later. Through the years, there were several iterations – some with you, some without. When you finally left, was it a difficult time for you? Were you ready to move on and try something new?

“It was not a great time, because prior to that there was a lot of litigation about who could use the name. That got worked out and it seemed like we were in a good way to continue, but then it quickly turned into one step forward, four steps back. In hindsight, it really wasn’t worth the trouble in trying to keep it together.”

When I played that riff from The Mob Rules and Ronnie came in, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. But then as we got into his solo stuff, it just didn’t match my style very well

You did some stints in Dokken and Whitesnake, and for a brief time you were in Dio.

“For a brief time, yeah. I got a call from [bassist] Jimmy Bain, who asked me to come down and jam. I said sure, and I went down to Joe’s Garage in the valley. I plugged into my rig and started warming up on Man on the Silver Mountain. Ronnie [James Dio] walked in and said, ‘You got the gig.’ He said, ‘We never played it like the record. We always played it really fast.’

“After that, we started working up material sort of chronologically, starting with Rainbow and then on to Black Sabbath stuff. It sounded amazing. When I played that riff from The Mob Rules and Ronnie came in, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. But then as we got into his solo stuff, it just didn’t match my style very well. The mirage of it working out kind of evaporated. But man, for a few days, it was heaven.”

What happened with Whitesnake?

“That was different, because other than the John Sykes stuff, I really wasn’t familiar with Whitesnake. We did a tour right when Geffen put out a ‘best of.’ It was in the middle of the Nineties, kind of when rock wasn’t doing so well. We toured Japan and Europe, and that was awesome because Ratt didn’t play Europe that much. We played in Russia, too, and had a great time. As a permanent thing, though, I don’t think that was ever taken seriously by David [Coverdale] or me.”

Ratt continues on without you. You last played with them in 2018. Would you say that band was a difficult alliance?

“You could put it that way.”

We talked about Charvel. You have a line of signature guitars with them.

“That’s right. We just came up with another color we’re going to add to what they call the ‘French’ graphic. There’s a red ‘French’ graphic that looks awesome, so that’s coming out. My Seymour Duncan RTM Rattus Tonious Maximus pickup is going to retail from the Custom Shop.”

Are you working on new music or planning to tour?

“Yes. I’m working on music all the time, but it’s hard to pin down when that’ll be ready. I have a lot of material, and it’s going to be completed when it’s completed. And at some point, if I live long enough, it’s probably going to be a solo effort, but I’m in no rush to put it out.

“As for touring, I love it. I’ve done that on and off for 35 years, so I don’t mind not being part of that world right now. I’ve been doing Kings of Chaos with Gilby Clarke, Matt Sorum, Kenny Aronoff and James Lorenzo. We do gigs once in a while, and there’s always three singers.

“The last gig we did featured Dee Snider, Ann Wilson and Billy Gibbons. That was a lot of fun. I do get out and play live, but no actual tours recently. It’s so hard these days with everything going on – there’s Covid and all. I think it’s better to wait for things to calm down out there.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Tom would say, ‘Play your guitar with a car key.’ It was very experimental”: Little Feat's Fred Tackett recalls Tom Waits' left-field approach to guitar playing – and his one-of-a-kind studio sessions

“Seeing friends and heroes of mine having their solos plagiarized broke my heart”: Giacomo Turra used their solos note-for-note for his own viral content. Now the guitarists who had their playing “stolen” are speaking out