Walter Trout: “I played with John Lee Hooker, with Big Mama Thornton, Percy Mayfield, Bo Diddley, Lowell Fulsom, Pee Wee Crayton… The list just goes on”

The blues-rock legend explains why he abandoned trying to play like Yngwie Malmsteen and Joe Bonamassa during lockdown, recalls the time John Mayall sent him a tape of his farts, and takes us on the emotional road he travelled for his 30th solo album, Ride

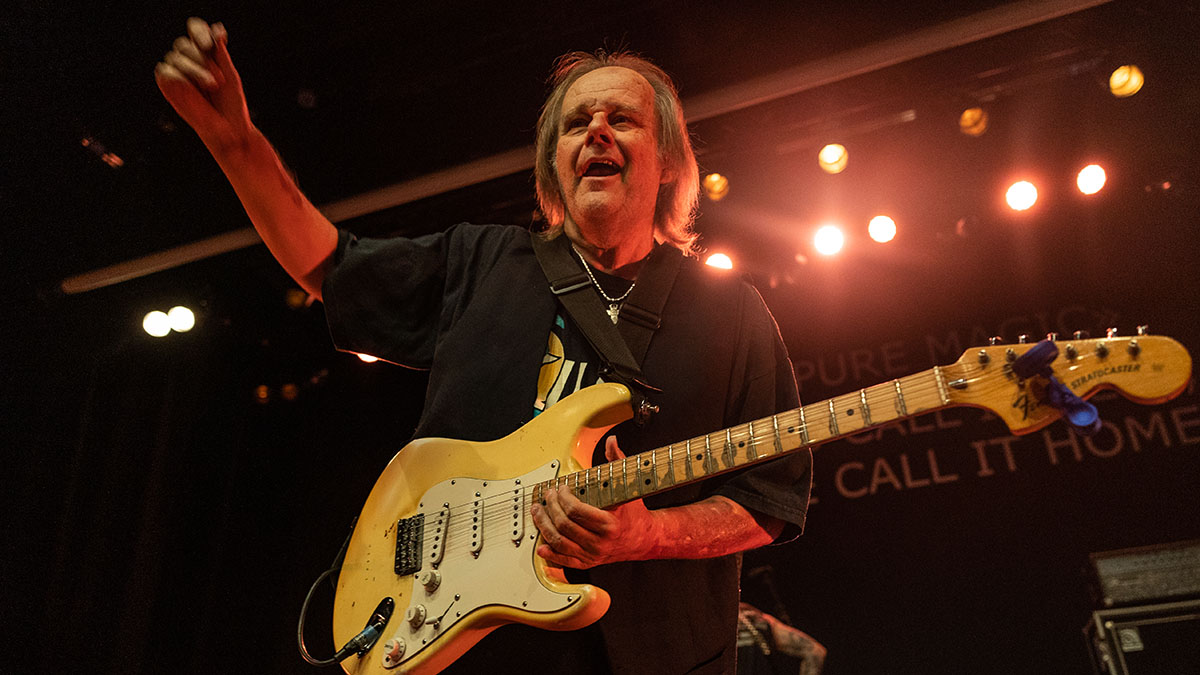

We are just five minutes into our interview with Walter Trout when he starts to well up. It’s been an emotional time for the 71-year-old. A few years ago Walter became so unwell that he required a liver transplant. He was holed up for eight months in hospital and it very nearly killed him. When he finally returned home he couldn’t walk, let alone play the guitar.

He recalls a conversation he had with his longtime partner-in-sound, Mesa/Boogie. Walter told them: “I can’t play any more, it’s gone from my memory, I don’t know how to do it. I’m going to start over.” They responded by sending him two guitar amplifiers. “They’ve never asked me to pay,” he tells us. “They just said, ‘We hope you get your music back.’”

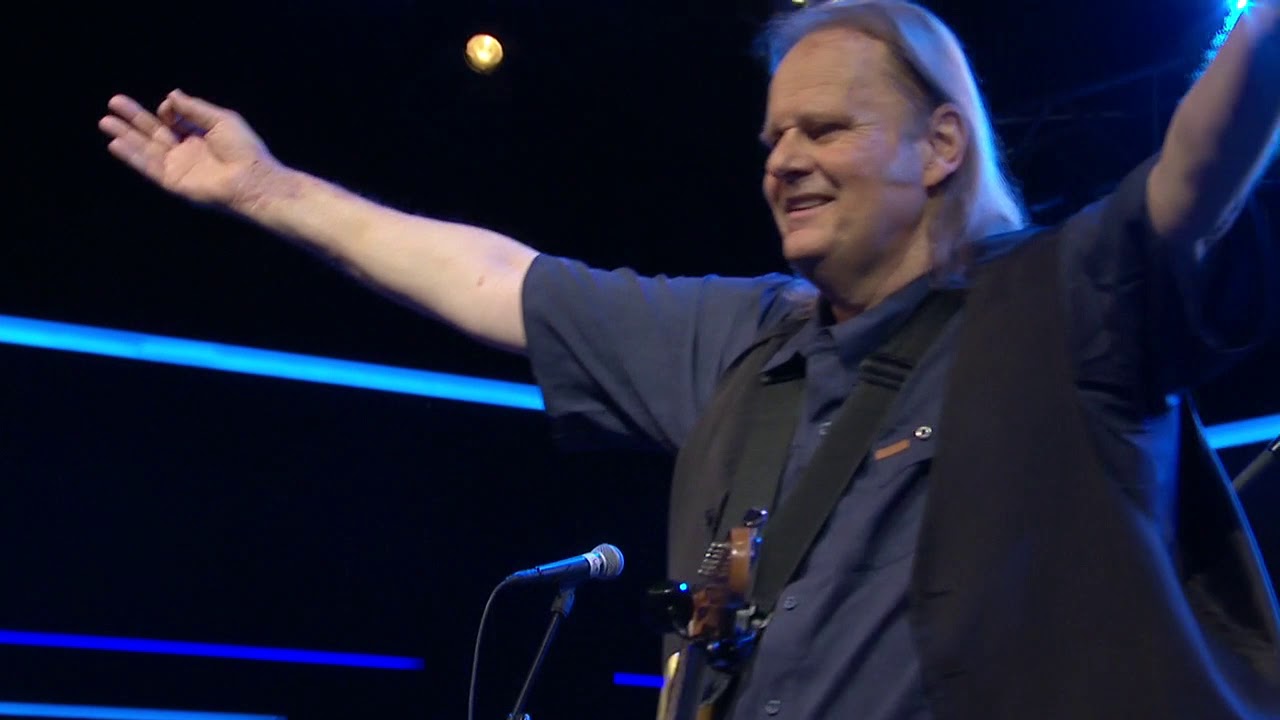

Talking in person to Walter it is easy to understand why Mesa/Boogie made this gesture; he is a smart and kind man. If you’ve ever witnessed Walter on stage you’ll understand that he goes into everything he does with full commitment.

Looking at his tour schedule, it’s hard to imagine where anyone would get the energy to continuously hop both sides of the Atlantic, let alone with a new liver and all the complications that puts on the immune system, especially in a world still dealing with the aftermath of Covid.

In fact, it was just a few years before the pandemic that Walter finally got back on stage, making a triumphant return at the Royal Albert Hall. He was frail and thin, but the fire never left him. Having finally got his groove back and his chops up to gigging speed, it all came crashing to a halt again, as the pandemic hit.

“We were out there killing it and suddenly it stopped, everything stopped,” he remembers. “And it’s hard to even find the words for what that felt like. One of the reasons is that after I faced death every day for eight months in that hospital, I am deeply aware of mortality – and how much longer do I have to do this? I am deeply grateful, I’m even going to lose it here,” he says as his voice starts to crack.

“Every day that I get to go on stage, and play to somebody, and look them in the eye, and see if I can create a feeling and an emotion in that person, and we can communicate – every day that I get to do that I’m overjoyed, and I’m grateful and thankful.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I’m a driven artist, I’m driven to create, and I’m driven to play, and I’m driven to write and to sing – and that’s my calling

Nevertheless, the forced hiatus sunk him into a state of depression, heightened by the realisation he was here on borrowed time. “[It created a real] depth of depression. I fought the depression, and I went and stayed in our house in Denmark with my wife and my family – we have a house in a little fishing village on the North Sea, population of 500 people.

“We’re in the middle of a national park, so we sequestered, and I spent time walking in nature with my wife and my kids, trying to just stop and enjoy life. But it’s very difficult. I’m a driven artist, I’m driven to create, and I’m driven to play, and I’m driven to write and to sing – and that’s my calling.”

Got the blues

During lockdown, Walter would spend hours every day trawling YouTube for lessons, staying connected to his guitar and his passion.

“I would go on there, and it would say, ‘Learn to sweep-pick like Yngwie Malmsteen.’ So I’d sit there and I’d do that for hours and for days, and see if I could get it down until I would say to myself, ‘I really don’t give a fuck about trying to play like this. I want to play blues-rock. Bloomfield! I want to be Mike Bloomfield; I don’t want to be Yngwie Malmsteen.’ But I was trying to expand my technique, especially because I only have three fingers.”

As if he didn’t have enough to deal with, Walter recently broke the little finger on his left hand, rendering it unusable. “It doesn’t work,” he says, “so I did spend a lot of time on [YouTube] trying to learn new techniques and new approaches. But that kept me involved, and I also wrote a lot of songs. I tried my damnedest to stay connected to my music.”

Walter came out of the pandemic with hundreds of song ideas, recorded on his American phone, his Danish phone and on his computer. Then, one day, his son Dylan asked his dad to join a Zoom call. And there, alongside his wife (and manager), Marie, were his band, his producer, Eric Corne, and Ed van Zijl, owner of the Mascot Label Group.

My wife said, ‘We’re doing this because your soul is melting away sitting on the couch, trying to learn how to sweep-pick,’ or whatever the fuck I was trying to do

With a chuckle he recounts: “Marie and Ed said, ‘For your birthday, we have negotiated a brand-new record deal.’ Then Eric said, ‘And I have booked a studio.’ And the band said, ‘We have gone and given our okay to the studio.… It’s now March 6, and in April you’re going home and making a record – and that’s your birthday present.’ My wife said, ‘We’re doing this because your soul is melting away sitting on the couch, trying to learn how to sweep-pick,’ or whatever the fuck I was trying to do.

“One day – I think Joe Bonamassa will appreciate this – I went on [YouTube] and it said, ‘Learn to play like Joe Bonamassa,’” Walter continues. “And I’m sitting there, playing this, and my keyboard player came on Zoom. He said, ‘Walter, play like Walter. You’re 70 years old, you already play like yourself – just play.’”

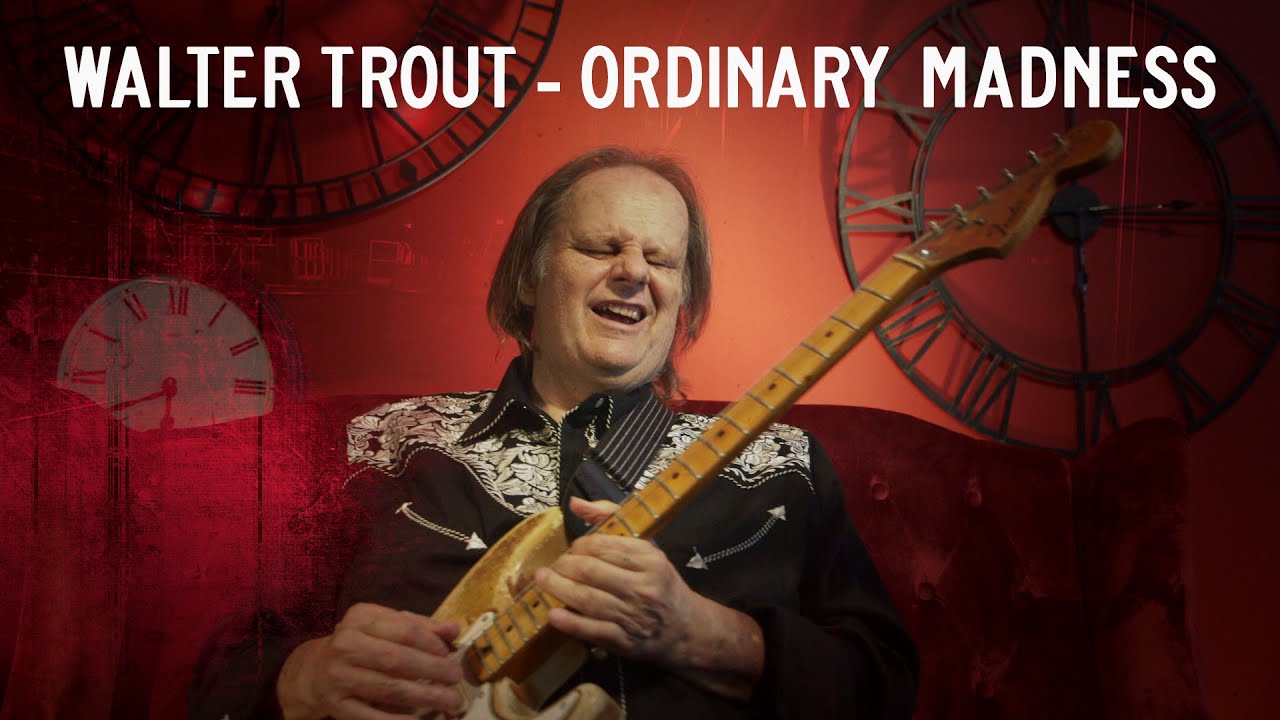

The resulting album, Ride, features 12 tracks full of fire, passion and a reflective honesty, with themes of life and death, and a strong thread of childhood memories.

“I started thinking about my youth, when I lived in a town called Laurel Springs, New Jersey – a little farm town,” Walter says. “We lived in a big old house right next to a railroad track, and I would lay in bed at night, and that train would go by, and the whole house would shake, the bed would shake.

“In the first couple of weeks it pissed me off, and then it calmed me down and it soothed me. I would fantasise about getting on that train and getting the hell out – because I was going through some real sort of traumatic stuff for a kid at that point with my home and family life.

The weird thing is, after the record was done and I sat and listened to it, I realised, ‘My God, probably 70 to 80 per cent of this album is about when I was a kid’

“I started thinking about that, and I took this song idea, and within about 10 minutes I had this song about that house. It took me three days to actually get the first song, three days of sitting around really kind of frustrated. ‘I’ve got all these ideas, what am I going to do with this?’

“And then that song came out about the house in New Jersey, and it’s called Ride, and it’s actually the title track of the new record. The weird thing is, after the record was done and I sat and listened to it, I realised, ‘My God, probably 70 to 80 per cent of this album is about when I was a kid.’”

Wild Ride

Walter credits John Mayall as being incredibly influential in his journey to where he is today. Mayall called Walter one day in the ‘80s and asked him to join his band. Previously, a chance jam with a blues band on a pier in Redondo Beach, California, had led to Walter joining John Lee Hooker’s backing band.

“I did that for two years with them. And with those guys, I played with John Lee Hooker, with Big Mama Thornton, Percy Mayfield, Bo Diddley, Lowell Fulsom, Pee Wee Crayton… The list just goes on. I was the guitar player and I learned so much about playing the blues from these guys. Because that was the real thing. I had not been in a blues band before.

“One day I was playing at The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, a legendary jazz club, and some kind of crusty biker-looking fellas came in and listened, and the next night they came back, but there were more of them. They came up and said, ‘We are Canned Heat. Would you like to join our band?’ The next thing I knew I was out on tour with Canned Heat, and about a year later Mr Mayall had the original Bluesbreakers back together, with Mick Taylor, John McVie and Colin Allen. We did three shows and opened for them.

“The first night John came up to me and said, ‘Man, I love the way you play.’ And at the end of the night he and I sat and talked for a couple hours about music, and we hung out. And I actually have a photo taken that night, a guy walked by with a Polaroid and took a picture of the two of us [pictured overleaf]. I took the Polaroid and asked him to sign it. I didn’t know I’d ever see him again.”

This was during Walter’s wild years – he is now 34 years sober – but back then the rock ’n’ roll excess was easy to fall into. The day after meeting John Mayall he stumbled across the Bluesbreakers back at the hotel and introduced himself: “‘Hi, I’m Walter, I play in Canned Heat. You guys sounded great last night. Why are you drinking rubbing alcohol?” To which John McVie replied: “89 cents a bottle.”

Walter had a better option: “I got a fifth of Smirnoff in my room,” he recalls saying. “Let’s go up. I’ve got the real thing.” They ended up drinking the whole bottle. “Got rip roaring drunk. McVie was passed out unconscious on the floor. I had music playing. I got up and said, ‘What does anybody want to hear?’ Suddenly, McVie’s head popped up off the carpet and he said, ‘Please, no Stevie Nicks.’”

John Mayall is one of the great band leaders of history. And he has this knack of finding musicians that can play with each other,

After those three gigs, John Mayall asked Walter to join the original Bluesbreakers, playing rhythm behind Mick Taylor. In 1984 he would join the band full-time in its new line-up, sharing guitar duties with Coco Montoya. Walter still has great respect for Mayall.

“He is one of the great band leaders of history. And he has this knack of finding musicians that can play with each other, and complement each other, and create the sum of the parts to become this great thing. And that’s one of his great talents, but he’s also, to me, one of the greatest songwriters in blues history, and he doesn’t get enough credit for that.”

Mayall also had an influence on Walter branching out as a solo artist. A promoter in Europe heard a tape of Walter’s band, who would play bars back in California. He offered Walter a run of shows. With the Bluesbreakers on a hiatus, Walter took a couple of the band members to back him up.

Walter always had great respect for the way Mayall would deal with band members on the road and before this trip Mayall himself warned Walter that, two weeks into the tour, they were all going to hate each other. In preparation, Mayall handed him a cassette tape, saying, “When that happens, I want you to play this tape.”

Sure enough, a fortnight into the tour, tensions were rising. Walter pulls out the tape and puts it into the vehicle’s cassette player. “Well, I guess it’s time for this mystery tape that Mr Mayall has given me,” he told the occupants of the van. “So I unwrapped it, I put it in – and it was 45 minutes of him farting! He had walked around for three weeks with a recorder, and every time he had to fart he recorded it. And he had done a beautiful label on it that said, The Farter of British Blues.” A different kind of ‘breaking’ than the blues for which we know Mayall!

As a band leader, Walter learned a lot from those years. “I try to, in many ways, emulate what I saw him do,” he says. “I want it to feel like a family, I want it to be joyous, happy, and we’re having fun out here. If things get tough, like you’ve got to do a 12-hour drive and a gig at the end and you’re all burned, let’s go out there like a team and let’s do it.”

Musical memories

Walter’s solo career really took off in the early ‘90s when he had a big break in Europe. “I had a hit in Europe on my second album, [Prisoner Of A Dream, 1991], a huge, massive MTV and radio hit called The Love That We Once Knew. And I still have charts from 1990 where it’s me, then Bon Jovi, Madonna and Bryan Adams – I was a one-hit wonder.

That was a song that I wrote about my high‑school girlfriend. It’s a power ballad, a ballad I did on an acoustic guitar, and we put it on the record. So I was writing songs back when I was 16 and 17, and my first two albums were basically 90 per cent songs I had written when I was just starting out.”

The colourful tales of touring are often thrown to the forefront when reflecting on a life lived in rock ’n’ roll land, but along with the laughs there is also a constant reminder of darker times.

“Sometimes, I wish I could maybe escape a little bit from getting caught up in the past, in reliving stuff. But sometimes I just can’t help it – I’m still very affected by memories, you know? I can’t block them out and they affect me deeply. There’s a lot of people that I loved who are gone, and I’m like, ‘What am I still doing here?’, you know?”

You hear a song and it takes you back to your living room, in that house by the train, when I was listening to Meet The Beatles!, and my stepfather’s drunk, chasing me around with a fucking axe, this kind of shit

Nothing encapsulates this sentiment more than the opening track on his recently released Ride album, Ghosts. He was driving through Denmark during lockdown when inspiration hit by way of a familiar tune from his youth. It was a trigger for Walter, both creatively and emotionally.

“It was something like House Of The Rising Sun by The Animals, or something by The Beatles,” Walter tells us, “and it brought back these memories of shit in my youth – some of it good, some of it bad. And I was weeping like a baby.

“I realised that nothing will do more to a person to bring back memories than music. You hear a song and it takes you back to your living room, in that house by the train, when I was listening to Meet The Beatles!, and my stepfather’s drunk, chasing me around with a fucking axe, this kind of shit. So I just pulled over and I wrote those lyrics down on a napkin.”

The lyrics tell the story: “I close my eyes and it don’t take long, ghosts appear to me.” It’s this unfiltered approach that makes Walter continue to stand out in a scene that owes him a big debt.

In the ‘90s when every guitar-led blues band seemed to be emulating the Texas shuffle of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Walter stayed true to his own approach to the blues – slowly but surely building a loyal following, not letting his ‘one-hit wonder’ status define him, all the time tuning the ear of his audience onto guitar-driven songs that weren’t afraid to mix incendiary riffs with an accessible and heartfelt vocal.

His influence and shaping of the genre is undeniable, especially in the UK, where the likes of King King, Aynsley Lister, Danny Bryant, Laurence Jones and Chantel McGregor are all crafting their own careers, using the bedrock of the blues-rock audience that Walter has nurtured throughout his last 30 years as a solo artist.

In another 30 years, it won’t just be his songs that serve as ghosts to those he influenced but also his overall resilience to push through any obstacle and continue to do what he loves.

His positive impact on all those musicians he has met – and invited onto his stage along the way – will stay with them, just as John Mayall did for him, ready to surface as inspiration when they find themselves in a funk. “What Would Walter Do?” should ring true on stages across the world.

Back here in the present, Walter has no intention of letting up. “I intend to go out as much as I can, and to keep doing this till I can’t do it any more,” he says. “Being a musician, I consider that a very, very noble pursuit. That is a beautiful, higher spiritual endeavour that we try to do, to bring some joy into someone’s life. And I intend to keep doing that as long as I can, whatever the circumstances.”

- Ride is out now via Mascot Label Group.

Robin Davey is is an English-born, LA-based musician, record producer, musical director and videographer. Robin formed UK blues rock band The Hoax, who were signed to East West records in the mid-90s. Other bands include The Davey Brothers, The Bastard Fairies, Well Hung Heart and blues rockers Beau Gris Gris & the Apocalypse, who also feature his partner Greta Valenti on vocals. The two run a video production house, Growvision, and produce our Pedalpocalypse series.

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“Such a rare piece”: Dave Navarro has chosen the guitar he’s using to record his first post-Jane’s Addiction material – and it’s a historic build

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)