“Prince liked the band. He would come see us. He would mysteriously appear and disappear, which always made me mad – ‘Damn it!’” How Vernon Reid’s expressionist shredding juiced Living Colour and won fans in Prince and the Rolling Stones

Unlike many bands that got big in the late ’80s, Living Colour’s sound didn’t require an overhaul to avoid obsolescence once the new decade hit. The prismatic metallics and social consciousness on the New York band’s 1988 debut album Vivid scanned alternative immediately.

Their dino-riff breakthrough hit, Cult of Personality, in addition to being one of rock’s best-ever singles, was an off-ramp from ’80s hedonism to the next decade’s underground-music uprising.

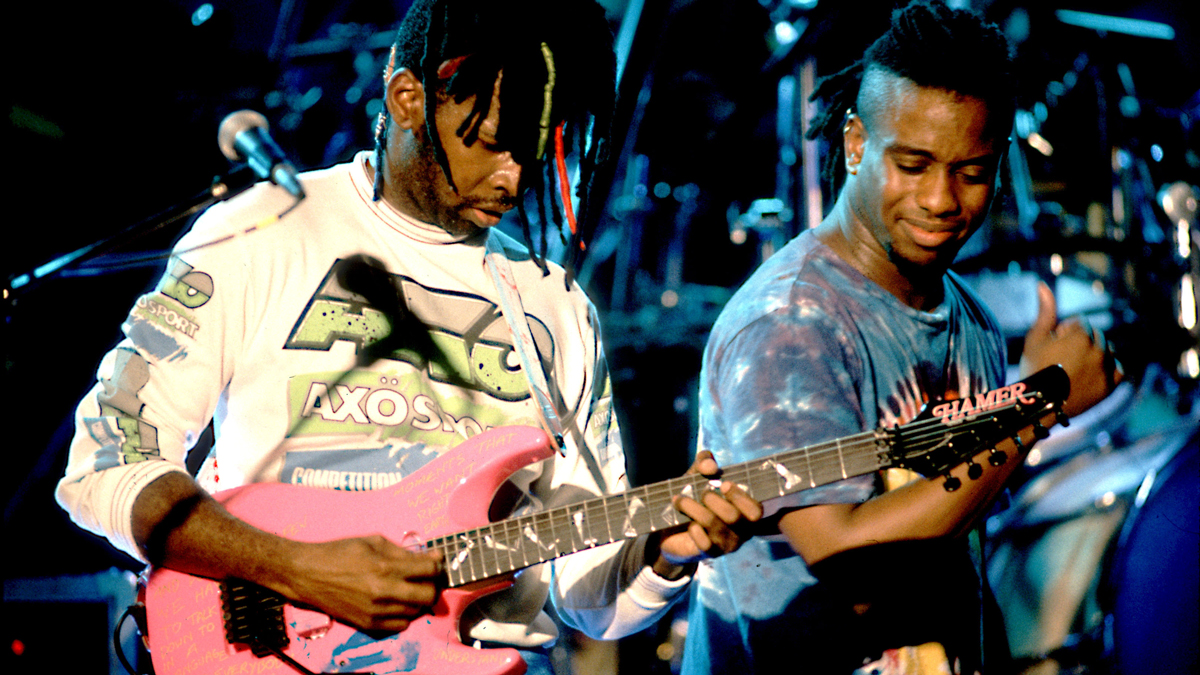

In a Reagan-rock sea of perma-sloshed white dudes, Living Colour was full of thoughtful Black virtuosos. So the band, which featured singer Corey Glover, guitarist Vernon Reid, bassist Muzz Skillings and drummer Will Calhoun, was a refreshing contrast to say the least.

Although they were future-proof, during the ’90s Living Colour’s music grew new vines.

“We evolved with the times in a way,” Reid, the band’s guitar-artiste, tells GW. “Vivid is a very upbeat record, even though we talked about social things. We were on our mission. We were happy to be in the mix. We were filled with a kind of realistic optimism, you know?”

In the coveted opening slot for the Rolling Stones’ 1989 U.S. stadium tour – Stones frontman Mick Jagger was a fan and did some production on Vivid – Living Colour saw plenty to reflect on. “And on [1990’s] Time’s Up,” Reid says, “we kind of took on a lot of the landscape around us.”

Time’s Up’s opening and gnarly title track served as a tip of the cap to another great all-Black band: Bad Brains, the Washington, D.C., hardcore combo whose roaring 1982 debut album has influenced musicians from Soundgarden to the Roots. “Without Bad Brains,” Reid says, “we probably wouldn’t exist. They were such an essential component of how we arrived.”

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Glover’s lyrics to Time’s Up were about the environment, a brilliant counterpoint to the track’s brass-knuckle grooves. “It was like, ‘This is novel,’ ” Reid says. “We just wanted to say something, and Corey came up with this completely unexpected conversation – and it worked.”

Without Bad Brains, we probably wouldn’t exist. They were such an essential component of how we arrived

Glover’s yearning, asphalt-opera vocals always peeled ears. On social media and elsewhere, Reid has maintained that Living Colour’s frontman is one of the greatest rock singers of an era overpopulated with star throats. And he’s not wrong. Meanwhile, the guitar-and-drums canyons Calhoun and Reid carved out are in the Page/Bonham ZIP Code.

“We have a lot in common in terms of our families,” Reid says of his connection with his bandmates. “We’re all children of the civil rights movement, those kinds of aspirations. That whole time period had a huge impact on us. The promise, the fear, the hope and all of that.” It’s a musical connection that energizes every Living Colour track – past, present and future.”

Love Rears Its Ugly Head was Time’s Up’s hit single and MTV video. (The song has since been streamed more than 13 million times on Spotify.) It’s a swinging, Prince-worthy mix of R&B and hard rock, and Reid peels off sauntering lead lines wiggled with a Cry Baby.

“During the making of the album, I bought a [Gibson ES]-345,” says Reid, who’s known for playing distinctively post-modern ESPs and Hamers. “I went to Norman’s Rare Guitars [in Tarzana, California] and we were kind of making a deal. I was getting a [Don] Musser acoustic and [the 345]; the salesman looked up the serial number and it turns out the Gibson was 10 years older [than what it was listed as].

“He was kind of freaked out. [Store namesake] Norman Harris came out and said the deal was made in good faith and the deal will stand. It was very formal. And it’s one of those great bargains. The Vari[tone] switch [which tweaks the 345’s tonal spectrum] didn’t work. But basically, I bought this guitar as if it was from ’68. And it turned out it was a ’58 or a ’60. I played that guitar on the track and in the video for Love Rears Its Ugly Head. ”

Reid says he and Prince shared a short yet sweet connection. “I did have a couple of moments with him. I wish we’d had more moments, you know? He liked the band. He would come see us. He would mysteriously appear and then he would mysteriously disappear, which always made me mad – ‘Damn it!’”

During sessions for Living Colour’s multi-platinum debut album, Reid’s guitar rig had been catch-as-catch-can. “I had a Dean Markley [RM-]150 amp when I was working on Vivid, plus a Fender Bassman and a Marshall,” he says. “It was a mess. It was a lot of different things. And then it became a little more systematized by the time of Time’s Up.

“I was using the MP-1 (guitar preamp by A/DA) and VHT power amps. It’s a pretty great combination. I’d started getting into the MIDI control system to organize everything. The MIDI Mitigator from Lake Butler Sound, rest in peace! A great company from Florida. They did MIDI control in a way that was practical and really cool.”

On the cinematic/frenetic Time’s Up cut New Jack Theme, Reid deployed a Bomb Squad-style tonal collage. Public Enemy’s landmark album It Takes a Nation to Hold Us Back frequently soundtracked Living Colour tour-van rides.

“That influence in that particular time period was very much in evidence,” Reid says. “I was messing around with different kinds of samples – and even Sustainiac coils in some of my Hamers. And there was a DigiTech delay, I think the [DSP] 256XL – it had some sample-and-hold stuff. It was definitely marrying a lot of different kinds of proto-electronics and things.”

In addition to his Walter-Payton-in-open-field fretboard burn, Reid’s tones and phrasing evoked visual artists like no other guitarist back then. Listeners could see Reid’s solos as much as they heard and felt them.

After I tell him his guitar playing sounds like Jean-Michel Basquiat’s expressionistic paintings look, Reid sounds legitimately touched. “Well, thank you for that. I’m not gonna make a big claim, but I knew Jean-Michel a little bit. He was on the downtown [NYC] scene. And I remember the first time I saw a Jackson Pollock painting, and that struck me.

“This is going way back to when I was playing with [avant-garde jazz group] the Decoding Society. Right when you got off the elevator in the Centre Pompidou in Paris, it was really the first time a painting kind of put me into shock. It was so visceral. And his rage, his thing, was so coming out of the canvas. That really struck me.”

One of my primary cultural and media experiences that really had an influence on me was The Twilight Zone. In the score, the first thing you hear is that guitar figure that lets you know you’re going into a dimension

Reid drew inspiration, like many guitarists before and since, from Jimi Hendrix’s Voodoo Child (Slight Return), which he connected to the voodoo-tinged imagery in Basquiat’s visuals. The work of genre-leaping writer James Baldwin affected Reid’s lyric writing, on tracks like Vivid gem Open Letter (to a Landlord).

“Baldwin’s whole concept was that he’s a witness,” Reid says. “So there were many different things that influenced me. I do believe in things having connections across boundaries.

“One of my primary cultural and media experiences that really had an influence on me was The Twilight Zone. In the score, the first thing you hear is that guitar figure that lets you know you’re going into a dimension. [Laughs] I didn’t start playing guitar until two years later. But as a kid, that show scared the shit out of me, and I couldn’t wait to see the next episode.”

There are only 12 notes. But Reid is one of a select group of guitarists who sound like they’ve found a 13th note all their own, as heard on his leads on Time’s Up sidewinder Pride.

“I’m kind of more of an improviser. But there’s a feeling that I want the solo to be,” he says. “There’s an effect I want to have, which is an outgrowth of whatever the song is saying. And very much so, in terms of Pride or the solo on Ignorance is Bliss from [Living Colour’s third album] Stain, I wanted it to be its own statement.

“Because the lyrics and melody are making one statement, and the guitar – particularly in how it comes in – has to stand as an adjunct to the voice. That kind of immediacy. And there’s a feeling of pleading on the solo on Pride. I’m really happy with how that turned out.”

The William-Burroughs-cut-up guitar intro to Time’s Up’s Information Overload, which sounds like a Tom Morello prequel, is one of Reid’s favorite personal guitar moments.

“It’s completely bonkers,” he says with a laugh. “That was, like, my first real experiment with extreme electronics. I’ve had a warm relationship with Eventide ever since. They’re very innovative. They’ve tried to stretch the boundaries of mad sonic innovation, and I’m very grateful to have the relationship I have with them.”

Living Colour was the only band that could’ve been a part of both the Stones reunion tour and the first Lollapalooza, the 1991 Jane’s Addiction-led traveling cavalcade that brought alt-rock to the masses.

“That’s pretty crazy, right?” Reid says. “Totally different modes. It’s pretty insane that we did both of those things. And they were both really important moments in the band’s life.” (Likewise, it’s difficult to imagine another rock outfit that could convincingly cover bluesman Robert Johnson and rap-god Notorious B.I.G., as Living Colour has done.)

By Stain, Living Colour’s 1993 album, the band had rebooted its low. Doug Wimbish, previously a part of early rap label Sugar Hill Records’ house rhythm section, replaced Skillings on bass guitar. Reid declines to compare the playing of Wimbish and Skillings.

“They’re both great in their own space,” he says. That said, he adds, “Doug is a master sonic craftsman. His command of sound effects… He kind of changed the game for bass in the way effects on the bottom are utilized. It’s incredibly inspiring.”

That manifested on songs like Stain closer Wall, where Wimbish’s bass goes from chain-link-fence to extraterrestrial.

“He exploits the full range of the bass,” Reid says. “That song dates back to Living Colour’s early days at [NYC punk-club mecca] CBGB. It was a good song, but it really wasn’t working. Basically, it just got completely rethought and resurrected. We were a different band from Vivid to Time’s Up to Stain, and, of course, the change in bass players was a major factor.”

The nose-punching Stain, released amid grunge cha-ching, out grunged the grunge bands without resorting to flannel-clad gravy-training. In an era when guitar solos were uncool, Reid’s arthouse shredding remained intact, as heard on songs like Mind Your Own Business. On Nothingness, the band was brave enough to sculpt soundscapes that weren’t particularly valued in mainstream rock back then.

Since they’ve started to introduce them, I’ve been a guitar synth advocate. I love it

Reid says, “We just wanted something completely with a different sonic palette that still had the force of something heavy. And it made that song very elegiac, really going for a sense of grandeur.”

Reid says Nothingness also shows his fondness for guitar synths. “Since they’ve started to introduce them, I’ve been a guitar synth advocate. I love it. A bunch of my guitars have the 13-pin Roland setup. I used the VG-99 for years, and one of the things about those early days was, are you going to get glitching? And what have you.

“But the thing is, we played that track straight [through]. It wasn’t like he had to piece it together, you know what I mean? And I think it’s also MIDI-ed to string things, so it’s a combination of tones, but it really worked well. It was like the universe had said, ‘OK, you can do this now.’ It was pretty cool.”

Amp-wise, by Stain, Reid says he’d “pretty much completely transitioned to [Mesa] Boogie and the Dual and Triple Rectifiers.”

Now in 2023, with Vivid having turned (gulp) 35 this spring, upcoming band projects include a Living Colour documentary, Reid says. The band also turned in a memorable set at Rock in Rio with Steve Vai guesting and trading alchemy with Reid.

Even though Reid’s a guitar-seeker in the truest sense, to this day he’s mesmerized by the simple symphony of a good riff. Smoke on the Water. Sunshine of Your Love (of which Living Colour notably Living Colour-ed a cover). The Isley Brothers’ It’s Your Thing. Even more recent stuff by the likes of Queens of the Stone Age.

“When you hear one of these riffs that are kind of basic or whatever,” Reid says, “you always go, like, ‘Damn. I wish I thought of that!’ Remember when [the White Stripes’] Seven Nation Army came out? Everybody caught that riff.”

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo