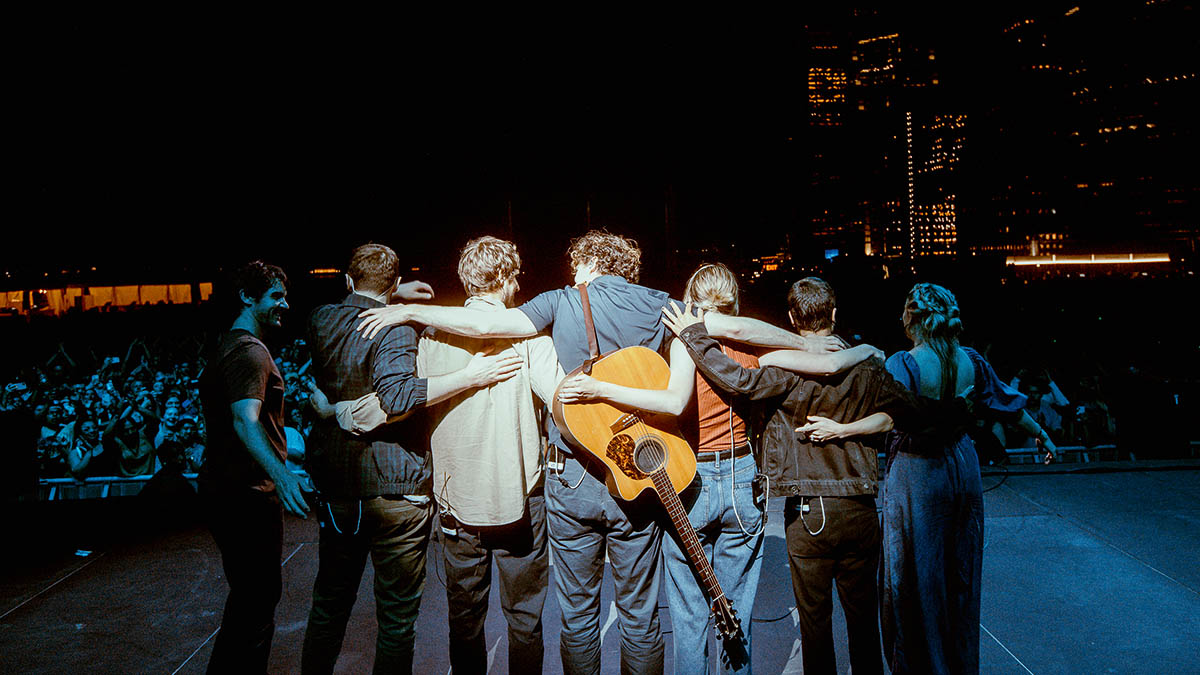

Vance Joy: “When you write a great song you’re just like, ‘How did I do that?’ You get chills or the hair stands up your neck. That’s what keeps everyone going”

The modern singer-songwriter fingerstylist keeps cranking out hits – but doesn’t care what gear he uses to make them... In fact, he doesn’t even know the names of his guitars

It’s rare for a new song to crack the list of essential beginner guitar tunes, but Vance Joy’s 2014 breakthrough single Riptide did just that.

Hitting just as school ukulele orchestras were becoming popular, the uke-powered folk-pop number proved an ideal starting point for strummers of all ages. It made Joy not just one of the world’s most visible young guitarists, but also one of the major inspirations for new beginners. Vance is still pleased at the impact it’s had.

“When I’m learning a song I go on tab websites. Sometimes there’s a list of all the most tabbed songs and Riptide’s in the top few,” he smiles. “I’ve walked past people busking it, and I’ve walked past kids playing it in little groups if one of the kids plays guitar. It’s cool that it’s had that effect. It feels like some people’s first song they learn either on ukulele or guitar, and that is cool. You just learn that down-up up-down-up rhythm and then you’re off.”

Now returning with his third album, In Our Own Sweet Time, Vance’s sound is still guitar driven. His fingerstyle patterns are more involved than we usually hear from pop stars, and this time the sophisticated guitar lines are augmented by lush arrangements including woodwind, horns, and piano for an epic indie-pop sound. Amidst all that, guitar holds the album’s centre of gravity. Vance is happy to discuss how he developed his style.

“When I was learning guitar, the songs I wanted to learn were just the most classic guitar riffs, and then Red Hot Chili Peppers songs and some Metallica intros,” he says. “The fingerpicking songs that I was inspired by and tried to play were Nothing Else Matters, then in one of the early theory books that I got when I was 11 or 12 there was a Spanish song, Asturias [by Isaac Albéniz], and then also Classical Gas [by Mason Williams] when I got a little bit better. I never really mastered that, but enough to play parts of it.”

Learning to play guitar while singing is a challenge for everyone, and Vance admits he prefers to stick to favourite patterns. “When I was 14 or 15 that was such a hurdle to get over, playing and singing even just simple chord structures. When I’m playing my own songs I usually stick within rhythms that I have down pat.

When I was 14 or 15 that was such a hurdle to get over, playing and singing even just simple chord structures

“There’s a few different fingerpicking rhythms I’m usually moving between. In all the songs it’s one of those three or four, probably. It’s always cool to learn a new one but when I’m playing those rhythms, singing is easy for me.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Every now and then if I’m doing a cover or playing a riff that I’ve overdubbed in a song and I want to include it live – that’s the stuff that does that thing [Vance pats his head and rubs his stomach]. Also, playing with the click in my ears, trying to stay in time with the fingerpicking rhythm. The more I do it the more I enjoy trying to trying to fit that those pieces together.”

In Our Own Sweet Time was driven by lead single Missing Piece, with a foot-tapping palm-muted riff. Vance thinks this is where his best songs start. “The riffs that feel the strongest begin the song and they inspire the melody. The whole song is built around it.”

He will sometimes begin with basic chords and develop a more involved guitar part later, but that’s not how he prefers to work.

“The times when I’ve just had a melody and chords, I’ve tried to make a guitar riff, and if it’s not really supposed to be a guitar riff vibe, I’ll just put it on piano and approach it from a different angle,” he says. “Starting a song it’s always good if you have a cool riff, but they don’t always come along so I guess you have to noodle around until something comes. I think the best riffs that I have, I wasn’t looking for them. They were just mucking around.”

When he was developing his fingerstyle technique, Vance was inspired by English folk singer Johnny Flynn, “because he has a lot of cool hammer-ons and pull-offs and little noodling cool bits.”

Vance discovered Flynn accidentally while working as a gardener, when a friend loaded Flynn’s songs onto his iPod.

“I was listening randomly to Johnny Flynn who I didn’t know about. I was like ‘This is awesome, I love these songs!’ and then I looked online and he was actually in Melbourne that night. I was like: ‘the stars have aligned!’”

He’s also a fan of Chris Cheney of Australian rockabilly punks The Living End. “When I watch him play I’m like, ‘Wow, this is like what a really gun guitar player sounds like. I suck compared to this guy!’”

Many of Vance’s songs make use of major and minor 10th intervals, made by playing the root of a chord plus the 3rd one octave higher. Typically he’ll play them using the A- and B-string notes from A-shape barre chords. Depending on the key, he’ll allow open strings to ring out too. They’re bright and colourful voicings that he stumbled upon by trial and error.

I don’t know the names of the guitars. I don’t pay great attention to it

“I got those shapes probably playing a cover of something. It might have even been an Incubus song. I used to play E minor shape with the two notes, and when I started moving that around I just saw it’s a nice simplified chord shape, with the open notes in the middle. I just explored that.”

Tracy Chapman’s Fast Car uses similar shapes, and Vance is conscious of the comparison.

“It’s actually hard when you’re playing those notes because that riff is just so memorable and classic. As soon as you hit some of those notes, someone listening might say ‘I just thought you were playing a Fast Car rip-off.’ You have to find a way to do your own thing.”

And yet for someone who loves the guitar so much, Vance is amusingly uninterested in gear. “I’ve got guitars floating around in different places,” he says. “Some of the songs I recorded guitar just into this laptop and in that case it probably would have been a Gibson that I have. I have a Maton which I’ve played on songs throughout, and then a Martin as well. I don’t know the names of the guitars. I don’t pay great attention to it.”

My bandmate, Sam, he’s just a great guitarist. If I talked to him about guitars I’d probably learn a lot, but for me I just pick it up and play

For Vance, guitars are tools for expression and if it works, he’ll use it. “Some of the tracks we recorded before Covid and on those songs it would have been the producers’ guitars. Whatever was available on the day we made the demo is often the finished product. I’ll pick up and play anything.

“My bandmate, Sam, he’s just a great guitarist. If I talked to him about guitars I’d probably learn a lot, but for me I just pick it up and play. Especially when you’re playing with in-ears, you don’t really always get a true reflection of the sound of the guitar.

“When I’m making decisions about guitars for the live show it’s more about getting information from the front of house techs. If everyone’s like ‘this feeds back a bit; this has a bit of a ringy string’ I’m like, ‘Let’s find the guitar that has none of those issues and then I’ll just play it.’ I don’t have any criteria so far.”

His lack of curiosity about gear extends to the rest of his rig, which was designed by a former tech and is maintained by his current one, Claire Murphy. He doesn’t know the details of how it works; lights on the inputs show where to plug in and which guitar is currently active.

“I’ve got three or four different guitars. I can just see which guitar is lit up, and I just have a tuner. I don’t think I have any preamps or anything like that,” he says uncertainly.

“For Saturday Sun on the uke, the tuning is totally whack. I only play it with a three-string uke because when we wrote we were trying to figure out the chord shapes on a ukulele where the tuning was really off. I don’t even know how to tune it up! Claire knows what the tuning is,” he laughs. He also has one Maton acoustic guitar tuned to D standard for songs that were recorded in that tuning.

Vance’s ignorance about technical details is because he cares more about the guitar’s creative possibilities. He loves the feeling of when, like “getting struck by lighting”, a song comes from nowhere.

“When you write a great song you’re just like, ‘How did I do that?’ You get chills or the hair stands up your neck. I think that’s what keeps everyone going.” Joy’s passion for invention is palpable. “There is a sense of cracking the code. You want those lightning moments and every day you go into a session excited by the possibility of that happening.”

- In Our Own Sweet Time is out now via Atlantic.

Jenna writes for Total Guitar and Guitar World, and is the former classic rock columnist for Guitar Techniques. She studied with Guthrie Govan at BIMM, and has taught guitar for 15 years. She's toured in 10 countries and played on a Top 10 album (in Sweden).

“I met Joe when he was 12. He picked up a vintage guitar in one store and they told him to leave. But someone said, ‘This guy called Norm will let you play his stuff’”: The unlikely rise of Norman’s Rare Guitars and the birth of the vintage guitar market

“This would make for the perfect first guitar for any style of player whether they’re trying to imitate John Mayer or John Petrucci”: Mooer MSC10 Pro review

![John Mayer and Bob Weir [left] of Dead & Company photographed against a grey background. Mayer wears a blue overshirt and has his signature Silver Sky on his shoulder. Weir wears grey and a bolo tie.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/C6niSAybzVCHoYcpJ8ZZgE.jpg)