“Why wouldn’t you stay in the Sphere and make a lot of money? Because it’s not as much fun. It doesn’t last forever. Look at how many musicians have passed away. What are you going to do with what you have?” Trey Anastasio explains Phish’s joyful rebirth

Most bands that survive for four decades enter into a nostalgic phase of their career. But Phish is on fire in year 41. The quartet, which formed in 1983 in Burlington, Vermont, released Evolve, their 16th studio album, in July.

Their 26-date summer tour includes Mondegreen, a four-day gathering in Dover, Delaware, that is their 11th festival and first since 2015. And they launched the year with a New Year’s Eve performance of Gamehenge, a song suite they hadn’t played since 1994, and which had taken on almost mythical status amongst fans. The two-hour performance included a cast and a production team that rivaled a Broadway show.

Other highlights of Phish’s year include a run at the Sphere in Las Vegas that featured 68 different songs across four nights with each song having original visuals – and their annual Mexican retreat.

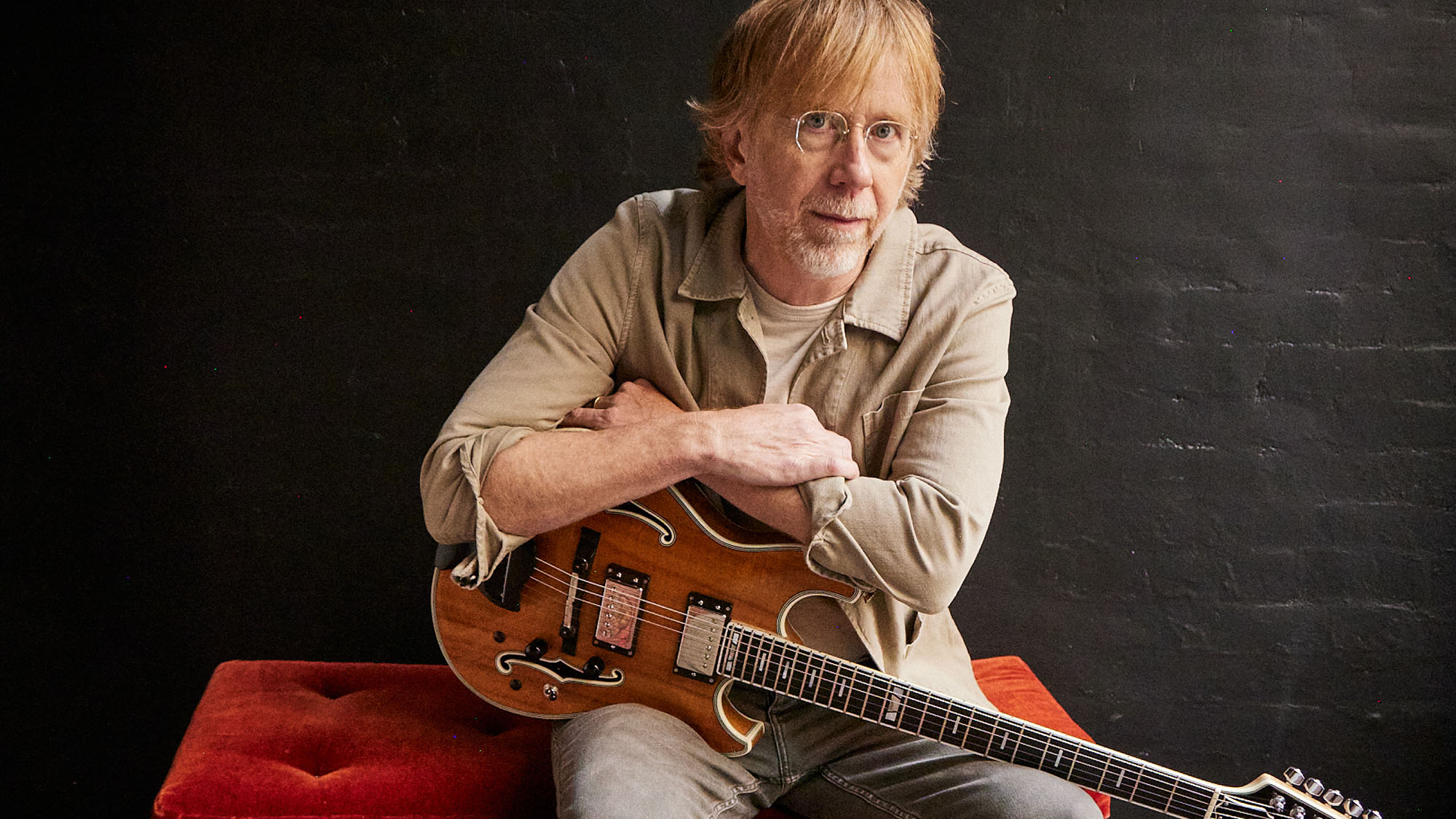

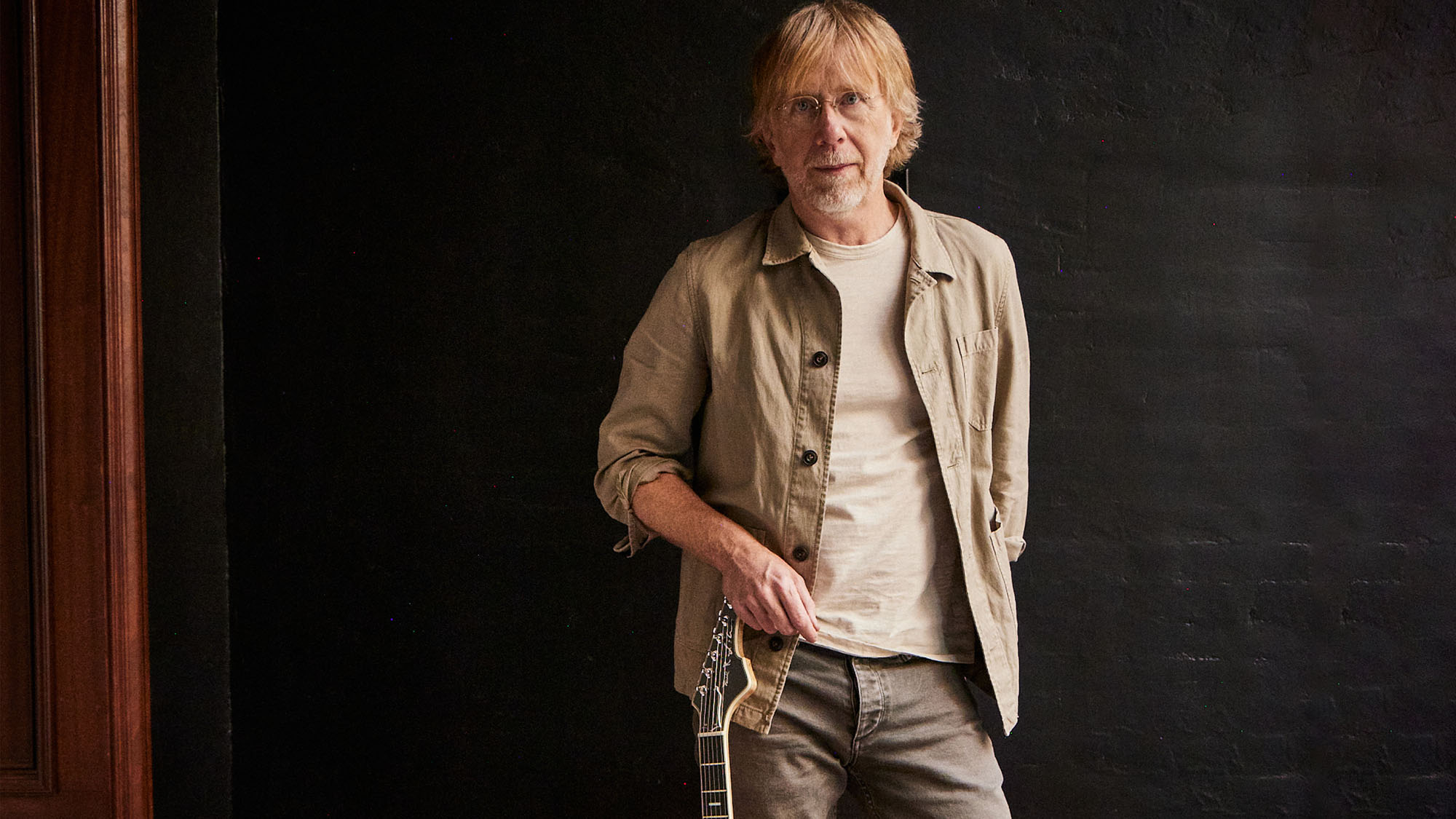

“This feels like a renaissance period for Phish,” says guitarist/singer/chief songwriter Trey Anastasio. “We don’t feel stagnant at all. This is a very vibrant period in our band’s life.”

As vibrant as Phish is right now, it is hardly Anastasio’s sole creative project. He is a man in constant motion, displaying boundless creative enthusiasm and energy. In addition to Phish, he tours regularly with the Trey Anastasio Band (TAB), a hard-charging outfit that includes a horn section. Additionally, New Yorkers have gotten used to Anastasio popping up on stages around the city, sitting in with the likes of Billy Strings, Goose, Tedeschi Trucks Band and even Billy Joel.

At 59, Anastasio says, he “feels like a kid again,” secure in his relationship with the three other members of Phish – drummer Jon Fishman, bassist Mike Gordon and keyboardist Page McConnell – and his 30-year marriage to his wife, Sue, and he’s happy that his daughters have launched into adulthood.

“It’s a new era in my life, and I’m loving it,” Anastasio says over a Zoom call from his New York City apartment, cradling one of his trusty Languedoc guitars.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Let’s be real – I’m lucky to still be here

Anastasio, one of the greatest and most influential guitarists of his generation, was particularly fruitful during the pandemic, when so much of the music world shut down.

He recorded and released four very different studio albums: December (2020), featuring duet versions of Phish songs recorded with McConnell; Lonely Trip (2020), which he calls a “demo album” on which he played all the instruments except some drums laid down by Fishman; the solo acoustic Mercy (2022); and January (2023), featuring new originals performed with McConnell.

Additionally, he put out the live TAB albums Burn It Down and The Beacon Jams, which was garnered from eight consecutive weekly shows played in an empty Beacon Theatre and broadcast on Twitch. Those free shows raised more than $1 million in donations to launch the Divided Sky Foundation, a Vermont facility dedicated to helping people recover from addictions, which is now open.

Anastasio’s own life was turned around in 2007 after he pled guilty to a reduced felony drug charge after failing a field sobriety test following a traffic stop in upstate New York.

He spent 14 months performing community service and participating in daily meetings in a drug court program, which he has credited with saving his life. Divided Sky, he says, is his way of giving back.

“I’ve never been part of anything that was so heart-filling, because let’s be real – I’m lucky to still be here,” he says. “Everything started again at that moment. I got so much help and want to help provide that for others.”

You came out of the pandemic like a fireball of creativity. How did that happen?

“When I started my sobriety journey in 2007, there was this feeling of reconnecting with everything joyous that you loved as a child. The pandemic was the next chapter in a weird way. Sue and I stayed in New York, and as soon as we were locked down, there was this feeling of joy that’s going to be hard for people to understand.

“I started my music career with a four-track machine in my bedroom. There was this magical moment that happened in the late-’70s, when I was in 10th grade, where the battery-powered four-track machine appeared and you could do a multitrack recording without having to go to a studio.”

“It was the beginning of this new world and I jumped in. That’s still the way I like to write. I love songwriting and the simplicity of recording myself. I’m such a dork, but I want you to see my little area. [He gets up and carries his computer into the corner of a room.]

“Every morning, I have my coffee and sit down here and write and it’s like going to heaven. I have a little keyboard, a little headphone, an acoustic guitar and something on my phone that’s the equivalent of a four-track machine.

“So why did I write so many songs during Covid? Because the road shut down, and suddenly I was home with the cat and Sue. My kids are grown up now, so I’m at a different stage and it felt like being given permission to do what I truly love, which is being creative.

“I started taping the camera to the wall and making all those videos; everything was with these great limitations. If I needed something, I got it. Like, I bought a bass on Amazon because I wanted it on those Covid albums, Lonely Trip and Mercy.”

So the isolation allowed you to re-set?

“Yeah. I know in different places in the country the lockdown wasn’t so big, but here in Manhattan, we never left. I just dug in and wrote so many songs, and a bunch of them are on this album. Three songs from Lonely Trip, which I call the demo album, are on Evolve – A Wave of Hope, Evolve and Lonely Trip – along with two from the acoustic album, Mercy.

“They’ve all developed so much. It’s not that different from how I’ve always done things, except I released the demos in real time because of the pandemic, because you couldn’t do anything else.

“The album Trampled by Lambs and Pecked by the Dove is a collection of four-track demos that Tom [Marshall, songwriting partner] and I made, which ended up being the first big round of Phish songs, like Twist, Limb by Limb and Water in the Sky, but people heard those demos after they knew the fully formed songs. This was the equivalent of releasing that in real time.”

The path that some of these songs took to be on a Phish album is a little different from the past, right? For instance, Hey Stranger started on Mercy, then you started playing it with TAB, and then it was a Phish song.

“It’s not that different, but people didn’t hear the demos like they heard these, and there’s nothing that unusual about songs crossing bands. Bug, Sand, First Tube and Everything’s Right were all TAB songs. A good song can move around.

“Quincy Jones really hits the nail on the head in this documentary where they ask him what he learned being the greatest arranger and producer in music for 50 years, and he says the main thing is that you can’t polish a turd. It’s either a good song or it isn’t. And the way for me to find that out is to play it in a lot of different contexts.

“I’ve now done six or seven acoustic tours and have found out that a good song will work solo; if you can’t play it on a stool with an acoustic guitar, it’s probably not good. Like Quincy said, the greatest arranger in the world can’t make a bad song good, and the worst arranger can’t mess up Somewhere Over the Rainbow. For me, it has to pass the alone-on-a-stool test.”

But some of your most beloved songs are the product of collaboration. I’m thinking of Reba, which is based around parts you and Page play together.

“Except that it started 100 percent on the guitar! I have a demo of it. The entire form of Reba was demoed on the guitar. Same with Harry Hood, which was an acoustic song I played on the beach start to finish, including all the time changes. Online, you can find the acoustic demo of Time Turns Elastic, which is a 28-minute orchestral piece. It didn’t become that until I sketched the whole thing out.

“When I was 18, my composition teacher taught me that all the composers started off by writing piano pieces, then orchestrated out. That’s where I got that concept – studying greats like [Maurice] Ravel. Here’s a good example: Before It’s Ice ever existed as a Phish song, it was a solo acoustic song.

“I walked around my hotel room every morning for two years writing the song until I could play it from start to finish. Then I taught it to everyone at band practice. You’re really onto an interesting subject – at least to my geek brain! But this is Guitar World, and I think it might be of interest to other guitar players. Do you agree?”

Yes – it’s something we all struggle with. Keep going.

“I write a song on acoustic, then I do four-track demos playing everything and figuring out the form. Then I write the lyrics down in my notes and go over them again and again. I edit freely until I have it exactly where I want it. Then I teach people the songs.

“For these new ones, I booked a round of shows at the Mission Ballroom in Denver with one person from TAB [bassist Dezron Douglas] and one person from Phish [Fishman], and we played all these potential songs as a trio. We did 25 songs, which was my attempt to put them through the birth canal and see what they sounded like in front of people.

I walked around my hotel room every morning for two years writing the song until I could play it from start to finish

“Playing with one member of TAB and one member of Phish was a conscious choice. There wasn’t a band attached to this. Then I asked our manager to look online and see what fans liked and what they said about the songs that resonated.

“I then played them on both a TAB tour and on the summer Phish tour. Then we played them in Mexico in 2023. When I got home, I did the most important part of all; I tossed all the band versions in the garbage and recorded solo acoustic versions of every single song that’s on Evolve.”

Did you have a vision of this entire process right from the start?

“Yes! Because I’ve been developing a system for 40 years, and before the Evolve album, I said, ‘This time I’m not skipping any steps.’ So step number one is home recording. [Holds up his phone and shows a series of recordings.]

“Then I go to a space with a bunch of instruments with Ben Collette, our engineer, and re-record all the songs with me playing everything in rudimentary form – Rhodes, bass, whatever. I call those four-track versions. My phone has tons of these.

“Then I teach the band and play a run, and the ones that rise to the top get played with both TAB and Phish. Now you’re at the Quincy Jones point. Then I strip it back down to acoustic; I did the whole Evolve as a fully realized acoustic album. This is the step that most people skip, but when you play it solo acoustic, the warts reveal themselves. Like, it’s not really in the right key; I need to slide that capo up so I can sing it better and then it can all change!”

“Now this gets exciting… Hold on. Just give me two seconds. [Anastasio walks away, then returns with his Languedoc ‘Koa 1’ guitar.] Alright, check this out. There can be magic to the key you write in, but when I go to solo acoustic, I often find it’s not the perfect place for my voice. I wrote Oblivion in C#, but that key wasn’t in the meat part of my voice, and it also doesn’t have any open strings or lend itself to sounding great.

“On the acoustic, I realized it sings better in B, and with a guitar in my hand, I realized B minor has open strings, and this riff got so much more rockin’ with them ringing out. [Plays riff.] You hear that?”

I sure do. In my notes on Oblivion, I wrote ‘very riff driven’. I was going to ask you if it started with the riff.

“You’re on it now! If you want to help young songwriters, this is it. I didn’t go to the key because of the riff. I went there because I sat on the acoustic guitar and worked on my vocal, which led me to the riff, which changed the arrangement and made the whole song so much better. None of that happens if I don’t go down to solo acoustic.

“Several great producers tried to tell me this. The first day I worked with Brendan O’Brien [on 2005’s Shine], he said, ‘Here’s a stool and an acoustic guitar. You’re not allowed into the studio until you can play me 12 songs fully formed in the right key. I’m not going to dork around until you have songs to work on.’ Steve Lillywhite told me something similar – and then it’s back to Quincy Jones: ‘It’s either a good song or it isn’t.’”

After you’ve gone through that whole process and you feel great about a song, does the band ever say it isn’t working?

“No, not really. [Laughs]”

Is there ever a disconnect – something you felt really strongly about but the audience didn’t seem to connect to?

“No. I’m now so enmeshed in the magic that our community has a lot more impact on where this band goes than they think. I find so much joy in writing that I’ve gotten comfortable accepting that if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. I can’t push an agenda. Let Me Lie is the big example. I really thought it was gonna be the best Phish song, but it wasn’t.

“I think it’s on three different albums, but it didn’t get legs, and when one does, you have a visceral, tangible feeling of communication when you play it live. Sometimes I get overruled, which happened on this album with Valdese, which I kept trying to cut because I don’t like long albums, and people kept saying it was their favorite song on the record, so I gave in to that.”

Since you’re so focused on composition, how do you look back at your ’90s self, guitar-playing wise? Was your approach similar? Because the general impression is that you were more focused on intricate guitar playing back then – and some of that stuff is awfully complex. Do you ever look at some of your old songs and say, ‘I can’t play this!’?

“I hope I don’t say I can’t play it, but there are definitely times where I wonder what the hell I was thinking. But my big secret is that the other thing that happened in this rebirth period is that I started practicing the guitar a lot more again. I have a pretty good practice routine now, and I’ve just found the joy in it all.”

I never used to practice singing, but anything you want to be good at requires practice and discipline, including singing.

In all playing?

“In all music, including practice. I never used to practice singing, but anything you want to be good at requires practice and discipline, including singing. I’ve been inspired by Jon, who does nothing but practice drums all day long on the road.

“A couple of tours ago, he reminded me of something I had shown him years ago, where Segovia said, ‘I practice two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon, no more, no less.’ It’s not an insane amount of practice, and I have a real system now, which Jon helped me with because he always knows what to do when he sits down, which is important.”

“On a good day, I have my technical hand practice, then my music practice. I do my finger exercises to music, usually dub reggae, Fela [Kuti] or King Sunny Adé, because there’s space and I try to always be playing music in lieu of a click. I’ll do them at the top of the neck and then the bottom. Then I play chords up and down, trying to connect the neck.

“Even though I’m not in the key that the song is playing, I still do it to music so that I’m jamming with somebody all the time. You’ve got to let go of the fact that the keys don’t always match or even embrace the question of how does this key relate to the wrong key I’m playing in? Then I go through the circle of fifths.

“Then I deal with ninth chords, or a circle of fifths where I walk up basslines in any position. Then I do another 1234. Then I do minor chords, like C minor up and down the neck. And I’m doing Hanon for guitar now, adapted from piano exercises.”

“This whole thing takes about an hour; I do it before every show now, and it’s just liberating. Then, most importantly, I do bends – all kinds, up and down the neck, always with the message that I learned from B.B. King. He said the worst thing that ever happened to guitar players is the electronic tuner because they don’t have to bend to pitch anymore. You have to practice bending to pitch, like a singer.

“I practice bending with my fourth finger, then my third. Then I practice vibrato. If you do all this to music, it’s not that disconnected from just having fun. I also do right-hand 1234s and then sometimes a little bit of chicken picking. If I had my way, I would do all this every day ’til I die.”

If life intervenes and you don’t do that for a day, what happens?

“It goes away really fast. After two days I feel terrible. Two days and it’s gone. Then you gotta get it back.”

Is it really gone, or is it psychological?

“I think it’s actually physical. Tension emerges. When I’m doing it every day on tour, everything feels so loose, and then you get in one of these jams and it just flows. I need to add the second part of practice I’ve had longer, it’s so simple: just listen to a song and play the melody. Any song. You think that’s easy? Try it.”

A reader told me that they had spent so much time trying to get Fly Famous Mockingbird perfect, only to realize that there were compromises in any position he played it in. He wanted to ask you if it just can’t be played at that original BPM.

“It can be played at that BPM, though I don’t know if I can play it the way I did when I was 25. [Laughs] That was before I had kids and I practiced guitar 10 hours a day. All I ever did was play the guitar.

“Then you have kids and it’s the greatest thing ever; you’re making breakfast, drying tears, walking to school and going to PTA meetings, and suddenly your 11 hours to practice are gone. And when the band starts taking off, you’re traveling so much… and all of that is why this is such an exciting period. I can pick up my guitar and play it all day, and it’s the best thing ever.

“But back to Fly Famous Mockingbird and your reader. If you’re not in the right position, you’re never gonna play it. It starts in second position, and then it slides up. Someday I should really do books about You Enjoy Myself, Fluffhead and Fly Famous Mockingbird and show the fingerings. I get asked to do it all the time but I’ve just been lazy.”

“But I’ve really always tried to find the easiest fingering. Joe Pass is the greatest jazz accompanist who ever lived. if you’re a guitarist who hasn’t listened to his work with Ella Fitzgerald, put this down and put that on right now, because that’s it! And his rule was ‘never play anything hard’ that something hard to finger leads to showing off, not playing music.

“His thing was figuring out what notes of this chord he can drop out so it can be easy and he can just react to something Ella sings. It’s the best advice. He didn’t mean, ‘don’t play a complex jazz song’; he meant ‘play it the easy way’ – and there are many ways to play a C9 chord; some of them a child could play.

“When I was writing all that complex stuff, I was obsessed with Joe Pass and asking if there is an easier way to finger this. But to get back to your actual question: no, I can’t play it anymore. [Laughs]”

As consistent as you’ve been with your guitar, you’ve messed with your guitar amp setup recently. Let’s discuss.

“I did a deep-dive amp study and I’m very happy with where I am. I played a Mesa Boogie Mark III for many years. This is gonna sound like an oversimplification, and I don’t want to start arguments in Guitar World, but the original Boogie was a souped-up Fender with an extra channel.

“It was basically a Fender Princeton custom-built for Carlos Santana, and a lot of people think the Princeton and Deluxes from 1965-67 were the high-water mark of Fender tone – and then the early Marshalls up to 1972 are the British tone.

“The Boogie I played was a slight variation away from a Fender, so in the Nineties, I went over to a Fender Deluxe. Starting on this last TAB tour, I’m playing through a Komet [60], which is like a hand-wired 6L6 Fender-y tone, and it sounds gorgeous. And then I’m very blessed to have a Ken Fischer Trainwreck for my lead tone.”

Is that the heart of your sound?

“Half my tone – the lead tone. I went on a crazy tone journey starting in about 2015. We were going to do this Bowie thing. I love Jimi Hendrix and I love the solo at the end of Kate Bush’s Wuthering Heights, which is the greatest tone. I wanted to try the soaring EL-34, British, Jimi Hendrix tone, which opened up this whole journey that I went on through about 2019.

Anyone who likes Layla knows the power of small amps, because that’s what they used. As did Jimmy Page in Led Zeppelin

“I started using these Komets, made by great guys who learned their craft from Ken Fischer, who built the Trainwrecks. And I got amps from Ken for my band in high school in New Jersey! Around 2019, I got this purple Komet, the same amp Mark Knopfler uses now. It’s essentially a really nice Fender.

“[Engineer] Vance Powell carries a vintage Princeton to every session, and he did Chris Stapleton, who also uses Princetons. Vance thinks it’s the only amp worth owning. Anyone who likes Layla knows the power of small amps, because that’s what they used. As did Jimmy Page in Led Zeppelin. On stage, he used all that shit, but in the studio he used a Telecaster and Princetons and other small amps. They sound the best.”

How did you go about playing without amps on stage at the Sphere?

“No one will ever have an amp on stage at the Sphere. They might have dummies, but they’re not on. The 52,000-speaker sound system comes down right behind your back. So there’s a slap back. That’s why anyone who will ever play there will have to have the drums wrapped in plexiglass.”

When you played the Sphere, you made the decision to do something different and special and take full advantage of the room. I understand you asked your tech people how many shows you could do where each one will be different. Is that accurate?

“One hundred percent accurate.”

U2 had a great one night. It’s just the Phish mentality that we didn’t want to repeat or have any cut-and-paste content. We wanted to use the thing, not just play another show in a new venue

You didn’t think that if you’re making all this effort, you should play 10 instead of four?

“We could have played 20 if we wanted to keep repeating. We had a lot more content than either of the other two bands that have played there. I think Dead & Co. mixed it up a little, but they were repeating by the second night. They probably have two and a half nights of content and they’ll just run it over and over again.

“U2 had a great one night. It’s just the Phish mentality that we didn’t want to repeat or have any cut-and-paste content. We wanted to use the thing, not just play another show in a new venue. We wanted it to be an art installation, and the best way to do that was to do the four.”

You have an amazing relationship with your fans. Often, when any artist has such a dedicated base, part of the tradeoff is that you have to give them what they want. But what your audience wants is for you to keep trying new things.

“It’s a give and take, which goes back to how, when and where we started, what Burlington was like in 1983. The drinking age was still 18, which was important not because of drinking, but because there were more bars per capita than anywhere else in the United States, and they all wanted bands.

“There wasn’t an emphasis on nostalgia and covers as much as on creating interesting and unique original music, which is what drew people through the door. So by 1984, we were playing songs like You Enjoy Myself and Maze. We were trying to find our place, and the crowd was smart and paying attention.

“We knew the original OG fans and what their favorite songs were, and it still feels like that. I just played eight brand-new songs over the course of 10 TAB shows, and there was this one dude standing in front of me the whole tour. I talked to him outside one night and thanked him, and when I got on stage I was thinking that I gotta honor this guy. He gave me the confidence to try a couple of new songs, which can still be scary.”

“It’s always been like that, which leads to the Sphere, where I wrote all this music for the atrium, so there was original music when you walked in the door and different walk-on music every night, Easter eggs that led you to the opening song. And we had special between-set music every night, and every single song had a visual that alludes to the narrative but was never literal.

“We had conversations about every one of these things, which I believe is honoring your fans’ commitment. Everybody wins, and hopefully it never feels like we’re just here making money, playing our hits repeatedly. Like, the Gamehendge thing was so much work for a solid year, so everybody goes, ‘Why don’t you just keep doing it after all that?’ Because we did it! [Laughs]”

I watched the video you put together of the rehearsals and realized that you worked up a Broadway show to do a single performance.

“Yes, and a lot of people thought this was insane, certainly those whose job is watching the books! I’m sure an outside person would wonder why anyone likes this. Well, I looked over and Page was crying because we did that at Nectar’s [the Burlington club that was their early home base], then a couple more times.

“It’s like, we’re still here, we’re alive, we love each other and we know who’s out there. We know what it means to them, too. Ninety-eight percent of humanity would see this craziness and ask, ‘What the hell is this shit?’ [Laughs] That’s what’s so great about it! It’s a strange band.”

And that long game is part of what keeps you so engaged. Are you excited about going back to having a festival this year?

“Oh, beyond excited. It’s bookends. The last three New Year’s things at the Garden were really fun – and building up to Gamehendge and the Sphere. The Mondegreen Festival is the bookend to this time period.

Our history with festivals is pretty deep, and it draws a straight line back to Bread and Puppets, a group of politically-minded hippies who had moved up to Vermont from New York in the Sixties and Seventies

“We love doing festivals, and we’ve been working for months with a really cool team. Our history with festivals is pretty deep, and it draws a straight line back to Bread and Puppets, a group of politically-minded hippies who had moved up to Vermont from New York in the Sixties and Seventies, some of whom have come on to work for us as art directors and other things.

“They made these giant puppets and they did these gorgeous fests, which inspired our first festivals, where we built in quiet time so that people could meet with their friends and experience the art. Modern festivals have a ‘more is more’ philosophy, with 110 bands and three playing at once, hitting you over the head. We’re going to try to bring back a little bit more pacing, and also the Phish weirdness.”

Let’s talk about Divided Sky, your residential drug treatment facility in Ludlow, Vermont, and what it means to you.

“It means so much. I had the idea for a while and the funding organically happened during the Beacon jams. I love those shows for so many reasons, mostly because it was free for people during that whole Covid craziness and it ended up being for a purpose. All these people in the community came forward and talked about their brother or sister or their best friend who struggled with addiction, and donated money, and we bought the place. It’s a 46-bed facility and we’re now open.

“On my last tour I met with John Curtiss, who started a program in Minnesota called The Retreat and has helped 30,000-plus people get sober. Our clinical director Melanie was my case manager in drug court when I got sober, and everybody who works there is sober.

Look at how many musicians we love who are passing away. It doesn’t last forever, so what are you going to do with what you have?

“It’s this beautiful spot amidst the leaves, but the final part was the reality check: if you want to do this nice thing and offer it to people, you must raise money. It’s a nonprofit, but you have staff, and we’ve been trying to figure out how to make this work. And John has taken a mentorship position, and he is such a help.

“I’m going to cry talking about this, but we’ve assembled an amazing board, and we have a viable program that’s working. It’s been a joyous experience. It’s a lot of work, but the clouds are parting and there’s a light shining through. I think it’s going to work.”

This explosion of creativity you’ve had all grew out of your sobriety, right?

“No question. I’ve been sober since January 5, 2007, and I’m very lucky in that I haven’t had to pick up a drink or drug in that time, and I’m grateful for that. It was the beginning of a long, slow journey.

“You have to find a different mojo than ‘I’m going to do a shot of tequila and be the funniest guy at the party.’ And then realizing that you weren’t really the funniest guy at the party except in your own mind. [Laughs] It’s also reconnecting with your real self, which got me into all this in the first place.

“I’m 59 years old, and I’ve been with Sue for 35 years. My kids are grown up. I drive a 2010 Volvo. I have the same guitar. So, what’s the point of all this? The sheer joy of writing and the birth of a song and then seeing people dancing in the audience and being with my friends on stage. In a weird way that answers all the questions you asked me.”

“Like, why wouldn’t you stay in the Sphere and make a whole lot of money? Because it’s not as much fun and what’s the fucking point? Look at how many musicians we love who are passing away. It doesn’t last forever, so what are you going to do with what you have?

“Why work for a year on Gamehendge? Because of the moment when Annie Golden [actress and performer known for the band the Shirts, the Broadway musical Hair and TV shows like Orange Is the New Black] dropped the needle on that record. Annie Golden and Tina Weymouth were my high school crushes, the two hottest girls in the game, and on New Year’s Eve, there’s Annie Golden up there with me.

“Gamehendge! Then the place goes wild and it’s a magical moment. Everybody’s laughing and crying and their non-Phish friends are scratching their heads and going 'Why would you care about this?' I can’t explain why it’s magical, but it is.”

Just having an unchanged band lineup for 40 years is magical, and the relationships that develop and grow and how well you can know each other. Like you, Trey, I’ve been married for more than 30 years and I know that when you get to a certain point in that relationship, it provides a terrific sense of security and a freedom to be yourself. I feel like that’s what has happened with Phish.

At a certain point in a marriage, you don’t fight anymore, because it’s like… we had that fight 10 years ago, so what’s the point? It’s like that with the band right now

“Yes! It’s so similar. At a certain point in a marriage, you don’t fight anymore, because it’s like… we had that fight 10 years ago, so what’s the point? It’s like that with the band right now. We’re really also conscious of what a blessing it is for the four of us to all still be in good health and to like each other after 41 years.”

And you had the good sense to realize at what point you needed to take a break in 2004, rather than ride it until it fractured.

“That goes back to driving the old car and having the same guitar. Because a lot of times people will keep grinding it out for money, but it’ll kill you in the end. And, like, what’s the game here?”

- Evolve is out now via JEMP.

Alan Paul is the author of three books, Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan, One Way Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as Managing Editor from 1991-96. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers, with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort.

“The main acoustic is a $100 Fender – the strings were super-old and dusty. We hate new strings!” Meet Great Grandpa, the unpredictable indie rockers making epic anthems with cheap acoustics – and recording guitars like a Queens of the Stone Age drummer

“You can almost hear the music in your head when looking at these photos”: How legendary photographer Jim Marshall captured the essence of the Grateful Dead and documented the rise of the ultimate jam band