Them Crooked Vultures: Top Flight

Originally published in Guitar World, March 2010

Combine Led Zeppelin's blues-inspired riff rock with Nirvana's post-punk aesthetic and the stoner metal sounds of Queens of the Stone Age. What do you get? Them Crooked Vultures, rock's latest supergroup, featuring John Paul Jones, Dave Grohl and Josh Homme.

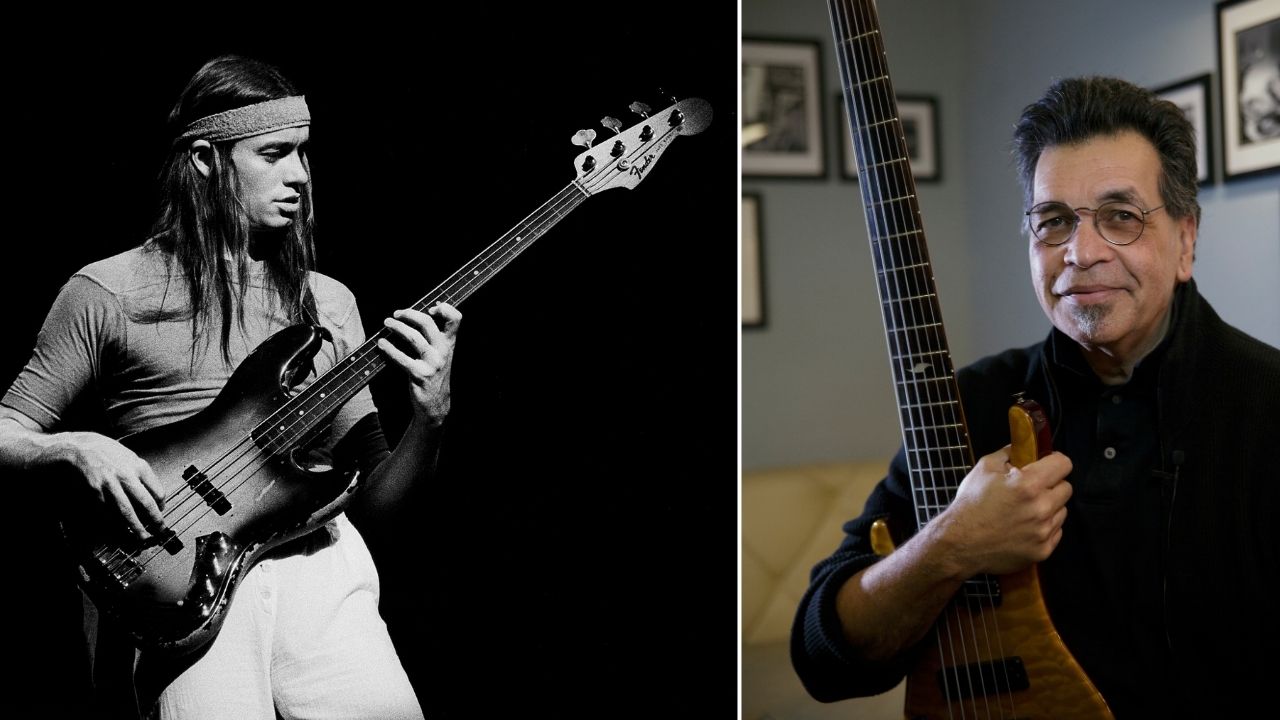

"All three of us have that gene that makes people want to do some crazy shit.” Dave Grohl is explaining the unlikely, but highly effective, chemistry of Them Crooked Vultures, the supergroup sensation that teams Grohl (on drums) with John Paul Jones (bass/keyboards) and Josh Homme (guitar and lead vocals). The group reflects the collective mojo of Led Zeppelin, Nirvana, the Foo Fighters, Kyuss, Queens of the Stone Age and the Eagles of Death Metal. Or to look at it another way, the band’s membership represents two of rock’s most influential decades—the classic rock Seventies and alt-rock Nineties—harnessed to some of recent rock’s most aggressive tendencies.

It’s a recipe for greatness…or potential disaster. Can those different musical influences actually coalesce into something coherent? Can three major rock stars put aside their egos and play as one cohesive unit?

“We’re all out to do something classic here,” Homme says. “And I know that in order to do it you have to take some risks. Risk nothing, gain nothing.”

And the risk, in this case, has certainly paid off. Them Crooked Vultures are a glorious affi rmation of the enduring power of riff-driven rock. Their phenomenal success offers tangible and eloquent proof that rock’s different generations can speak to one another across the divide of decades and changing fashions. The band’s self-titled debut album alludes heavily to the power-trio heyday of Led Zeppelin and Cream. Yet the Vultures’ take on this legacy is distinctly 21st century—angular, jagged and deconstructed, with nothing taken for granted, and grainy sounds that fly at your head from some aural phantom zone located midway between analog filth and digital degeneracy.

“Josh Homme has got loads of chops,” Jones says. “But he’s very quirky. He doesn’t really do anything like anybody else. He’s always very exploratory in his tones and how the guitars are amplified. He looks at things in a different way.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That includes the very nature of Them Crooked Vultures. Homme isn’t keen on referring to the band as a supergroup. And he’s dead set against calling it a side project. “I don’t do side projects,” Homme says. “And it would be a real shame if that word ‘supergroup’ were valid. To me, what that means is people cashing in on what they’ve done in the past as if it were what they just did.”

Actually, the burden of history was exactly what all three men were looking to escape when they gathered at Homme’s Pink Duck recording studio in Burbank, California. “I would have had a huge problem,” Homme says, “if I had gone in there thinking that I was going to compete with Kurt Cobain, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant. But I’m just trying to be myself.”

Them Crooked Vultures grew out of a friendship that Grohl and Homme forged in the early Nineties, when Grohl dropped in at a show by Kyuss, the stoner-rock group Homme performed with from 1989 to 1995. The two musicians continued to rub shoulders on the L.A. rock scene after Grohl, in the wake of Nirvana, formed Foo Fighters and Homme created Queens of the Stone Age, but their friendship deepened when QOTSA toured with Foo Fighters in 2000 and Grohl played on the Queens’ 2002 album, Songs for the Deaf.

“When I started playing with Queens of the Stone Age, I realized that Josh and I have this musical connection that I don’t really have with anyone else,” Grohl says. “So after the Queens of the Stone Age project, I wanted to get back and jam with them again some time. But Josh and I never had the time; we were always on tour with our respective bands. We’d bump into each other out on the road and say, ‘Fuck sitting on a tour bus and doing interviews all day long. Man, let’s do a project!’ So then I had this idea. I said, ‘What if we called John Paul Jones?’ ”

“When Dave mentioned Jones, I thought he was kidding,” Homme admits. “And there’s a part of me that still thinks he is, that maybe this is all some elaborate joke on me.”

Grohl and Jones had become friendly around 2005, when Jones did some work on the Foo Fighters album In Your Honor. “I had met Dave just before that,” Jones says, “at one of the Grammy ceremonies where they gave Led Zeppelin a Lifetime Achievement Award. I invited Dave to sit at our table, and he did. And then I did In Your Honor, and after that I did an orchestral arrangement of the Foo Fighters song ‘The Pretender’ and conducted the orchestra at another Grammy Awards show. And then Dave came to the GQ Awards in England and asked whether I’d be interested in playing with him and Josh.”

Grohl adds, “I was presenting the award to Zeppelin in London. Robert [Plant], Jimmy [Page] and John were all there, and after the ceremony I just kind of cornered John and asked him if he wanted to do this project with me and Josh. John’s an incredibly hip guy. He knew all about Josh and his work. But he didn’t say yes right away. We traded emails for a while. Finally he said, ‘Okay, I’ll come over, and let’s jam.’ So I called up Josh and said, ‘Holy shit, he said yes!’ ”

Grohl had approached Jones at an advantageous moment. The bassist had just come through the drama that unfolded following Led Zeppelin’s wildly successful 2007 reunion concert. Jones, Jimmy Page and Jason Bonham (son of original Led Zep drummer John Bonham) wanted to keep the band going, but Robert Plant wasn’t interested. So Jones, Page and Bonham tried, unsuccessfully, to soldier on with another singer.

“We’d done so much work together, it seemed crazy just to leave it at that,” Jones says. “So we thought we’d start another band. It wasn’t going to be Led Zeppelin, as was reported in the press. We wanted to write new material. We auditioned some singers, but we couldn’t agree on one, and it all fell by the wayside. So by the time Dave mentioned this thing with Josh, I was in the mindset to do some recording and playing.”

When the three men convened at Pink Duck, none of them knew exactly what was going to happen. “It was very strange,” Homme says. “I almost felt like I wasn’t there, in a way. I guess I always think of myself as someone from a small town in the Mojave Desert. I feel outside of the music community a lot, so to be there playing with Jones was just a little otherworldly for me. I felt like I was hovering above it all. But Dave and John were playing together miraculously as I stood and watched. They were so locked in. That first day we were doing what I would essentially call ‘muso’ stuff, not trying to test or lose the other person but just seeing how far we could go that first day. The second day was when we really got down to work and began writing songs.”

Grohl recalls, “It wasn’t long before Josh said, ‘Hey, I’ve got a riff.’ I think the first riff we jammed on was ‘New Fang,’ which became our first single. We wrote a middle section, and within an hour or two we had an arrangement.”

All three parties quickly concurred that making an instrumental jam record was not the way to go. Grohl says, “I remember saying to Josh, ‘Dude, we could fill the Grand Canyon with riffs, but what we really need to do is write songs. So let’s focus on songs and not so much on riffs.’ ”

Homme adds, “We were really adamant about doing songs and having moments in them when we could jam.”

Pink Duck was ideally suited to the group’s creative process. Located in an old, Fifties-era building near Burbank Airport, the studio (which Homme shares with his wife, Brody Dalle of Distillers/Spinnerette fame) is a homey place, with antiques, old wallpaper, a big chandelier, kitchen and art from Josh’s grandmother. “Josh has a nice SSL [mixing console] in there, along with an arsenal of crazy, messed-up gear,” Grohl says. “There are instruments hanging everywhere, on the walls and on racks. Usually what would happen is we would jam a bit, walk out of the room, sit down and have tea or coffee, and maybe I’d pick up a fiddle and start dorking around. John would pick up a mandolin, and Josh would grab a guitar. Someone would start playing, and we’d all join in. If it sounded like we had a song, we’d say, ‘Okay, well, let’s go in and jam on that.’ ”

In short order, a band dynamic started to emerge as their individual personalities began to emerge in the sessions. Homme can be a fairly intense guy, adamant in his opinions and possessed of a kind of desert rat, daredevil, rugged individualist philosophy that might not be out of place in the trenches of Iraq or Afghanistan. “I know that for some people I’m very polarizing,” he admits. “But I wouldn’t have it any other way. I don’t want to be everyone’s buddy.”

Grohl’s demeanor is almost the exact opposite. Affable and laid-back to a fault, he exudes a kind of quiet humility born of his roots on the Washington, D.C., hardcore scene, where it was considered the ultimate bad form for anyone ever to act like a rock star. Even though Grohl now is a rock star, he still carries that unassuming attitude.

“Josh is very conceptual,” Grohl elaborates, “whereas I tend to just go for it without thinking too much. There’s a lot of thought in everything Josh does. So when he’s presenting a riff or a song idea, he’ll talk about it for 10 minutes without even playing the guitar: ‘Okay, this riff is a three-parter, right? It starts out with this tempo that sounds like elephants walking and holding hands...’ Finally I’ll say, ‘All right, could I just hear the riff already? Am I allowed to hear it?’ ”

Jones often played a mediating role between Grohl and Homme’s divergent musical approaches. “John’s a brilliant arranger,” Grohl says. “He’s famous for that. So he was often in the middle when Josh and I were seesawing on opposite sides. I’d try to standardize stuff, and Josh would be saying, ‘I have this song with 17 different parts, and nothing repeats.’ And I’d say, ‘Okay, wait: Shouldn’t we maybe repeat something? Like maybe twice at least?’ And John would have to say, ‘No, he’s right,’ or, ‘Yeah, you’re right.’ ”

The eldest of the three musicians by several decades, Jones exerted a stabilizing influence. He began his career as a session man during the mid-Sixties British Invasion, playing bass, keyboards and arranging horn and string charts for everyone from the Rolling Stones, Jeff Beck and Donovan to Dusty Springfield, Tom Jones and Cat Stevens. The studio is his métier. His career progressed from session anonymity to the Hammer of the Gods excesses of Led Zeppelin’s heyday. There is little, or nothing, that the man hasn’t seen. And nothing ever seems to crack his quiet, polite, middle-class British reserve.

“John silently challenges everyone,” Grohl says. “His presence makes you play the best you can possibly play, because you don’t want to let him down. And if you can keep up, you’re doing okay.”

Jones seems aware of his effect on his fellow musicians, but he notes, “The pressure eases once you’ve got some tracks down. Half a dozen songs and you think you’ve got something and you can breathe a little easier. That’s what happened with this record.”

One challenge that all three players faced was how to forge a common approach to the blues. That musical legacy is everywhere on the album, albeit spectrally, a presence sometimes felt more than overtly heard, yet unmistakable, hovering like Banquo’s ghost over this triumvirate of rock stars. The blues is the undeniable mojo behind the power riffs of Them Crooked Vultures, and for musicians of Jones’ generation, it has always reigned supreme as the wellspring of all great Sixties and Seventies rock. While Homme, like Grohl, comes from the post-punk hardcore tradition, which quite deliberately spurned the blues, his connection to the genre was almost umbilical.

“I grew up listening to Blind Lemon Jefferson, Chuck Berry, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf,” he says. “My parents listened to an eclectic range of music. For them, it was all those blues guys, along with Kenny Rogers, Jackson Browne, the Doors and Jimi Hendrix. So blues, to me, always seemed to be about lost moments, lost causes and mistakes. And being where I was from, in the middle of the desert, that all makes sense to me. I’ve always felt like blues music kind of died. Maybe this isn’t nice to say, but when Eric Clapton started playing acoustic guitar, and Robert Cray...like, that stuff’s not blues to me. To me, that doesn’t speak like Howlin’ Wolf. I don’t mean to slam them, but when it’s got a sweater tied around it, it doesn’t feel like blues to me.”

Many players who grew up right after the Sixties or Seventies find a way into the blues via Led Zeppelin or early Clapton. But not Homme. “What’s funny is I grew up on punk rock music,” he says. “Black Flag was my Led Zeppelin until I was 22 years old.”

Thus, in an odd way, Homme shares some early blues influences with Jones, but missed out—at least during his formative years—on the way Jones’ generation recontextualized the blues. Grohl, for his part, doesn’t worry about the whole thing too much. “When we first started talking about this,” he recalls, “Josh said, ‘Yeah, man, I got this whole new version of the blues.’ And I said, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’ But I kind of get it now. I know where he’s coming from.”

“Josh seems really bluesy in his phrasing,” Jones allows. “It’s kind of a bastard blues, I suppose. A perverted blues. But we all love big ass-kicking riffs, which is where Dave comes in as well.”

Homme, Grohl and Jones produced the album themselves. But the trio did have engineering assistance from two industry greats: the British engineer/producer Alan Moulder (Nine Inch Nails, Smashing Pumpkins, My Bloody Valentine), and Alain Johannes, a veteran of the band Eleven and an adjunct Queens of the Stone Age member who has since become the touring second guitarist for Them Crooked Vultures. Johannes recorded three tunes on the album—“Dead End Friends,” “Reptiles” and “Interlude with Ludes”—and generally made himself handy around the studio. For example, when Jones decided he wanted to play Hohner clavinet on the track “Scumbag Blues,” Johannes pulled a vintage one out of his own closet. “It was a very old version that I had actually never seen before,” Jones marvels. “It looked like it predated the Hohner clavinet that I had in Led Zeppelin. It had a great sound. Alain’s got a house full of instruments like that.”

As for Moulder, he’s certainly no stranger to great guitar tone, having produced and/or engineered some of the most influential guitar records of the past two decades. Homme says, “Alan is someone who could be like us, but behind the mixing desk. He could interpret our requests, create options and understand our sensibility. Alan could assimilate that situation and be a part of it without overtaking it. The same with Alain Johannes.”

Thus capably assisted, the trio felt its way into greatness. “It wasn’t really until about four months in that it started sounding like an album,” Grohl says. “I think the first song we recorded was ‘Spinning in Daffodils.’ And after that, I think, was ‘Scumbag Blues,’ ‘Caligulove’ and ‘New Fang.’ So we were shooting in a bunch of different directions in the first couple of weeks. What we would do was come into the studio, hang out, record for two weeks and then take two weeks off. Then we’d come back, record for another two weeks and take two more weeks off. And at each of these two-week sessions we would record maybe five or six songs. It was just a free-for-all.”

Some songs developed over the course of multiple sessions. “ ‘Warsaw’ was a song that we wrote, arranged and worked on for a day and half,” Grohl says. “But when we came back later on, Josh said, ‘Okay, I think the beat should go like this.’ And it was entirely different than the version we had recorded. And I thought, Wait a minute, haven’t we already finished this song? Aren’t we on to something else? But Josh said, ‘No, no, no. Check this out.’ And we put in that sort of Texas shuffle that you hear on the record, and it quickly became one of my favorite songs that we have. And live, that one is like an atom bomb. It’ll tear your head off.”

Jones says, “We’d work on a couple of tracks, do some overdubs and then be working on a couple of new tracks at the same time. The whole thing just grew organically, as it were. And then Josh came in and did the lyrics, in the end.”

And then there were two. With the basic tracks completed, Grohl took off to work on the Foo Fighters’ 2009 compilation, Greatest Hits, leaving Jones and Homme to complete overdubs and lead vocals. “All of a sudden, Josh was left alone in the studio with John, and I think he was a little spooked,” Grohl says. “But I believe he finally got over his weirdness, and the two of them hit it off famously.”

It was a moment Homme had been dreading. “I’ve spent my whole career avoiding situations where I have to write melodies and lyrics to pre-arranged music that has none. But there was no other way to do it with this band. The music had to come first. But it’s such a difficult process to be suddenly staring down the barrel of 18 songs with no lyrics and everybody else is ready to go. It wasn’t easy. I definitely broke a few things. A few guitars, one child’s drum set and a couple of other things didn’t make it. But that’s when Jones and I really came to understand each other a little bit more—like being in a foxhole together.”

“Josh was trying out melodies, and I was supplying some melodies as well,” Jones recounts. “And he was writing lyrics. I was glad I was there to help him through that stage. It gets a bit lonely, especially for a singer. Everybody else is done and you’re just left having to put the vocals on. I was there with him for that.”

So how would you like to stand up in front of Led Zeppelin’s legendary bass player and bare your soul, performing some lyrics you’d just scratched on a pad? “My best example of that is the song ‘Mind Eraser,’” Homme says. “I’m holding lyrics that say, ‘Mind eraser, no chaser.’ And Jones and I are just getting to know one another. I’m thinking, I don’t even know if I like these words or if they’re any good, and here I am trying them in front of new people. And by new people I mean Jones!

“But in a lot of ways, that’s the moment when we bonded. When I first sang ‘Mind Eraser,’ Jones came into the control room and said, ‘Fucking all right. Brilliant, man. Let’s go.’ That’s when I realized that Jones is a crazy motherfucker. He sees the beauty in the darkness the same way I do. And the darker it gets, the more excited he gets. And the more excited I get too. It became a spot where we really locked arms and charged together.”

This latter stage of the project was when some of the album’s more experimental tracks came into being. The track ‘Interlude with Ludes’ grew out of sampled keyboard loop that Jones stumbled upon. “I liken it to what they might play in the lobby of Hell as you’re entering,” Homme says. “A seasick welcome. We later showed it to Dave and said, ‘Will you play drums over it?’ He started to play my kid’s drum set, and we were like, ‘Will you play it worse?’ until he finally played some of the worst drums I’ve ever heard. It was a beautiful moment.”

Grohl laughs about his efforts on the track. “It sounded like a shoe caught in a clothes dryer! And then Josh put some spooky guitar over it.”

The album project gave Homme occasion to dig deep into his collection of bizarre little combo amps and other arcane gear. His uniquely distressed, and always compelling, tones are derived from an unlikely combination of funky junk and devices never meant to amplify an electric guitar signal. “Josh is famous for his huge guitar sound,” Grohl says. “But most of the amps he uses in the studio are the size of a Kleenex box. He knows how to mic ’em. He’ll line up four of five pedals in front of a tiny Gorilla amp with a six-inch speaker, and it’ll sound like God is pissing in your ears.”

The album was not quite completed, and certainly far from being ready for release, when Them Crooked Vultures decided it was time to take their music to live audiences. “We just wanted to get out there and play it,” Jones says. “I’m pretty sure Dave wanted to get out and play even before recording, but we had to lock in to the studio for a bit. As soon as the album was actually recorded, however, we just started doing shows. We had to do some mixes and mastering at the same time.”

“We put a lot of thought into how it was going to happen,” Grohl says of the initial live dates. “Because what are you going to do—put a poster on the wall that says, ‘Guy from Zeppelin, guy from Nirvana and guy from Queens of the Stone Age are playing tonight?’ And where do you do it? At the arena down the street? In a beautiful old theater? In a little club? Do you tell everybody? Do you make it a secret? How do you make the experience real?”

In the end, Them Crooked Vultures opted to do a series of surprise gigs at theatres (the Brixton Academy in London, Roseland Ballroom in New York) and clubs (the Metro in Chicago). “The very first concert, nobody was quite sure as to who they were seeing,” Jones says. “There were no names mentioned. They just put up a black page with three symbols.” The symbols consisted of the Foo Fighters’ double-F logo; the Queens’ icon, a Q represented by a sperm entering an egg; and Jones’ triquetra symbol from the cover of Led Zeppelin IV. “It was brilliant.”

Surprisingly there have been few audience requests for Zeppelin, Nirvana, Foo Fighters or Queens of the Stone Age songs at the shows. “I can only remember once when someone shouted out a request in Portland,” Grohl says. “Josh just said, ‘Nah, we’re not a cover band.’ ”

“We’ve got a special thing going here,” Homme says. “The tour sold out in 10 minutes, before the record even came out. No one knew a goddamn stitch of music and the whole thing sold out. I’ve never even heard of shit like that before. I would have bought a ticket. But I’m lucky enough to actually be onstage doing it. It’s pretty awesome.”

Them Crooked Vultures is something that Homme, for one, would like to see continue. “We all want to do another record,” he says. “I don’t know when that would be or if it’s even gonna happen. But we all want to. I know the next record would be, like, ‘sophomore jinx, my ass,’ ’cause we know one another now. We were actually just hitting our stride in the studio when we knew we should stop. That was one of the main struggles. ‘Dude, we’re just getting going.’ But we knew we shouldn’t take too long. This stuff, if you’re not careful, turns to vapor. We gotta live in the now.”