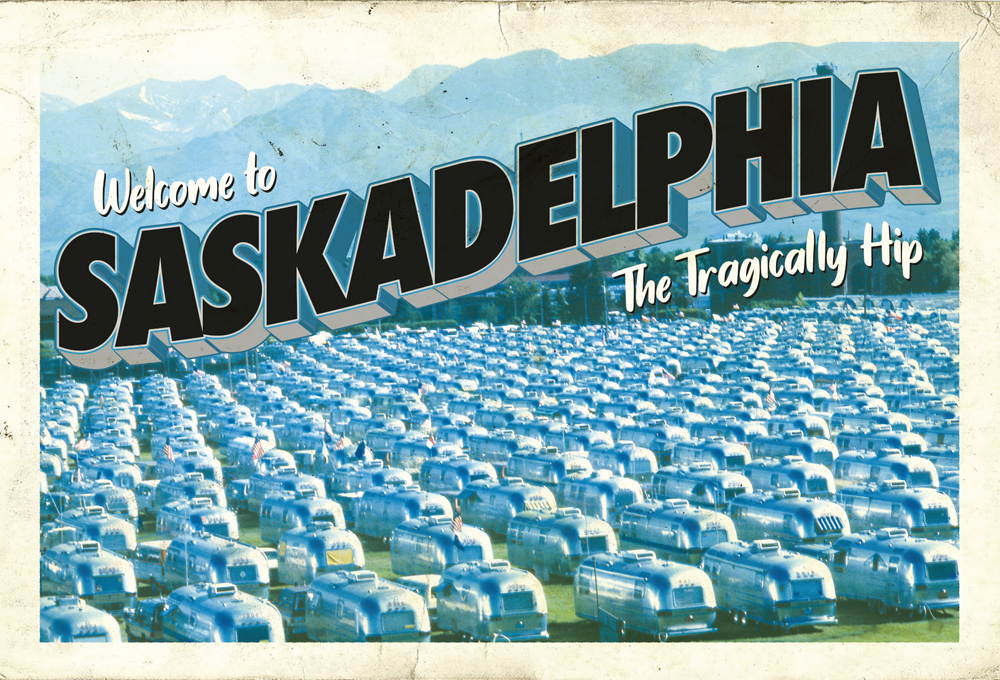

The Tragically Hip's Rob Baker on how the Canadian rock icons unearthed their long-lost sophomore sessions for surprise new EP, Saskadelphia

The Hip's guitarist explores the gear that helped create the new archival release, how his playing changed over time, and why you're unlikely to hear the band's Mötley Crüe cover any time soon…

Earlier this spring, iconic Canadian rock group The Tragically Hip surprised fans with the release of Saskadelphia, comprising tunes first recorded in 1990 during the sessions for their sophomore album, Road Apples. That the outtakes still exist for us to hear is a miracle in and of itself.

A New York Times article from 2019 erroneously listed that The Tragically Hip were among countless artists who had lost their treasured masters in the infamous 2008 Universal backlot fire. While The Hip’s recordings had at one point been stored out in Hollywood, the group mercifully managed to get the tapes back to Canada years before the blaze. Still, once the story hit, the band decided it was high time to re-evaluate the archive.

Formed in Kingston, Ontario, The Tragically Hip’s debut album, 1989’s Up to Here, gained traction thanks to brawny, blues-based booms, like crossover hit New Orleans Is Sinking. Follow-up Road Apples, fittingly tracked in NOLA, likewise trafficked in 12-bar structures. While single Twist My Arm was a lean, funk-pushing strut, Little Bones, in contrast, was a meaty, adrenalized rocker. The album is arguably the beginning of the parameter-shift that continued through to The Hip’s final album, 2016’s Man Machine Poem.

Saskadelphia maintains that same kind of balancing act, whether pushing the tempo into overdrive for Reformed Baptist Blues, or easing back towards a moody groove on Montreal, on which vocalist Gordon Downie sang of the 1989 École Polytechnique terrorist shooting that left 10 women dead.

Though the songs of Saskadelphia were setlist favorites circa 1990, they were ultimately edged out by fresher successors like Little Bones, which fully blossomed in the Big Easy.

“It's not for lack of quality,” lead guitarist Rob Baker explains. “I know that on Up to Here my two favorite songs got cut, and on Road Apples my favorite song got cut.”

Though The Hip have mostly been out of the public eye since the passing of frontman Downie in 2017 following his battle with brain cancer, the surviving members reunited this spring for a televised performance of It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken, with singer-songwriter Feist taking on lead vocals.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Saskadelphia project, meanwhile, may be the beginning of a broader, ongoing archival project for the band.

Speaking to Guitar World from his home studio in Ontario, Baker got into what they’ve found so far, he and co-guitarist Paul Langlois’ gear list for Saskadelphia, and which iconic metal cover from the sessions will most likely be kept under lock-and-key.

Saskadelphia showcases lost songs recorded in New Orleans throughout the Road Apples sessions, which is an interesting transitional period for the band. It’s a record that explores your 12-bar beginnings, but also runs towards these raw rock anthems. Could you sense that shift in the direction at that time?

"Yeah, a little bit. We weren't looking for a makeover, but we aren’t AC/DC either. I love AC/DC, don't get me wrong, but you can take any song of theirs and put it on any album and it wouldn’t be out of place, right? They just do what they do, and they do it better than anyone else. Why change?

"For us, it was a slow evolution. We'd been through that whole baby blue album [1987’s The Tragically Hip EP], which was us trying to figure out what we wanted to be – having tons of material and not even realizing we're making a record, just thinking we're demoing and then suddenly it's a seven-song EP.

"Then we did [1989’s] Up to Here. We were very focused on making it a good record, and I think we did, with the help of [producer] Don Smith. Then it was like, 'What do you do next?' We were very aware of the sophomore jinx.

"We went down with a lot of songs and a lot of different material, and you can hear that. The material goes in a lot of different directions, and yet I think that it's still cohesive because it's the five of us and we're very much all on the same page."

The material goes in a lot of different directions, yet it's still cohesive because it's the five of us and we're all very much on the same page

What was behind the decision to hole up in New Orleans?

"Great A&R guys are worth their weight in gold, and we had a great one in (former MCA Records vice-president) Bruce Dickinson. He suggested Memphis for Up to Here, and also suggested Don Smith. It was a perfect pairing.

"In his mind, he was thinking, ‘Well, they've done Memphis, so let's take them deeper south to New Orleans. Daniel Lanois has got this gigantic mansion down there that has a vibe all its own – we’ll have Don Smith at the helm and it'll be awesome.’ And it was!

"It was a six-week session. We had a day to get our bearings and five days of pre-production at a little wooden warehouse in the Ninth Ward. That's where Little Bones and The Last of the Unplucked Gems came from, and they bumped other songs that eventually ended up on Saskadelphia.

"Then we were in Lanois’ place for a full five weeks, and we just played from 10 in the morning til’ 10 at night, every day."

This definitely gets blurrier as the band goes on, but in those early days, especially, I tend to visualize Paul playing a Les Paul and you hovering more towards a Strat. Can you recall the general setup through these sessions? Was there much in the way of experimentation, gear-wise?

"I've seen pictures of myself playing a ‘50s Tele, which would have been Lanois’. I’ve also seen pictures of myself playing a ‘69 SG, which I got at a pawn shop in Memphis while making the first record, but I know it's not on Road Apples or Saskadelphia.

"I think every song was played on my brown ‘73 Strat, and Paul was on a Tele Custom for virtually everything, though he may have played a Les Paul on something.

Guitar-wise, we went to the studio with very little. I had my guitar, my amp, a wah pedal, and a Tube Screamer. That was it

"I think Paul was already playing Randall amps, but also splitting it with something else. I was playing my Boogie amp – a Mark III head and a 2x12. Lanois had a ‘59 Fender Bassman in mint condition and it made an appearance on every track, either from Paul or I, and maybe even [bassist Gord] Sinclair. Lanois had great amps! He had Vox amps, Fender amps, Gibson amps – a great collection of old classic gear.

"Guitar-wise, we went down with very little. We were a young band and didn’t have a ton of gear. So I had my guitar, my amp, a wah pedal, and a Tube Screamer. That was it."

How long was the ‘73 Strat your number one for?

"That was my main guitar right through to [1992’s] Fully Completely. After that I relegated it to being an open E guitar, because I started playing more open tunings. I never take it out of open E anymore; it just rings like a bell."

It had been falsely reported that The Hip’s earliest recordings were lost in that big Universal backlot fire in 2008, though you’d actually got them back up to Canada before then. When did you decide to start poring through the recordings to make Saskadelphia?

"Well, we knew the material was there. I don't know about other bands, but our band was always most excited about the song we were currently writing, so the newest song would always push the oldest song off a record.

"The Universal fire thing just lit a fire under us to try and find out where our stuff was. We had a special deal where master tapes reverted to us, but we still haven't found all the tapes.

Road Apples was a unique session. We would just play in the studio like it was a live gig. That was how we treated it

"We were searching for tapes right up until we had the packaging for Saskadelphia done. We were still searching because we knew there are other songs out there, but we've only found 35 out of 60-plus rolls of tape.

"Road Apples was a unique session for us – we didn't run as much tape on any other album. Don Smith loved his two-inch tape! He loved hearing the band play, and he set us up in a room on monitors instead of headphones. We would just play like it was a live gig. That was how we treated it.

"He would just get the best sounds he could, and didn't care too much about bleed. It's just a band that was road-ready; we’d been playing 250 shows a year for about three or four years in a row."

There are, naturally, parallels that can be found between the material on Saskadelphia and Road Apples. Both the former’s Ouch and the latter’s Twist My Arm, for instance, share a lithe funkiness to them. What can you say about experimenting with that kind of feel?

"It didn't feel like an experiment; it was just that we were way into that. As a cover band, we played some James Brown songs. Sinclair and I grew up on all that ‘70s funk and soul, and were way into Joe Tex, James Brown, Barry White – you name it. It didn't seem unnatural to us.

"It was also around the time the Red Hot Chili Peppers were just kind of cracking. We were wary of that, like, we didn’t want to be mistaken for them or lumped in with them, so we just did the two songs.

"We were leaning towards Ouch [for Road Apples], but Twist My Arm really jumped out in the studio. It was one of the only songs that I did an overdub on – I overdubbed the guitar solo – and it came off well. I guess we thought that two funky, blues-based numbers on the record is one too many. We didn't want to mine anyone's territory and pigeonhole ourselves into something."

Saskadelphia’s Not Necessary and Crack My Spine (Like a Whip) both have that classic, driving Hip feel to them. Do you recall the decisions behind pulling those off Road Apples?

“Not Necessary was probably the first song that we wrote for Road Apples. We road-tested it for several months. As far as we were concerned it was a shoo-in, probably the single, but while we were in New Orleans, Sinclair had a little acoustic guitar piece that became Little Bones.

"Gord Downie had a chorus that he sang over this acoustic guitar piece, and during the pre-production it just evolved into something else. It became a driving rock song with a tempo very similar to Not Necessary. It was the new one, so the older one got bumped."

Reformed Baptist Blues has a very different kind of raucousness to it than the other songs, almost like a Jackson-styled country ripper…

"That goes way back to when we were playing the bars in ‘85 and ‘86 – it predates the baby blue EP. Crowds loved it because it's sort of a relentless punch-in-the-face, but it had long gone by the wayside. It had been out of our set for a couple of years.

I tried to do all the solos live off the floor. You're going 1,000-miles-an-hour and you're just hanging on for dear life

"One afternoon in the studio Don said, ‘Okay, let's just empty the cupboards. I'm just getting sounds here, play anything.’ We played Reformed Baptist Blues and Dr. Feelgood – whatever was on the radio at the time."

You’re talking about the Mötley Crüe song?

"I think it was on the radio in the months leading up to us going down to New Orleans. We weren't really Mötley Crüe fans, but there's a certain admiration there. We enjoyed it, so we just knocked it out as a one-off."

Is that on any of the reels that you’ve found so far?

"It’s there… People don't need to hear everything [laughs]."

Reformed Baptist Blues might feature the most epic, extended solo section on Saskadelphia. Was that all live off the floor?

"I tried to do all the solos live off the floor. On a song like Reformed Baptist Blues or Crack My Spine, you're just trying not to fall off the horse. You're going 1,000-miles-an-hour and you're just hanging on for dear life. 'Don't play bum notes' was all I was thinking."

One of the recordings you couldn’t track down was a studio take of Montreal, which is represented on Saskadelphia by a live recording from 2000. What can you remember about the original session?

"I know we had a crack at it, and we tracked it, but we haven't found that tape. Montreal and Fight were written the same day during rehearsal at my parents' house. The Montreal massacre had just happened, so it was very fresh for everyone. Gord had poignant lyrics.

"We didn’t revisit it after the Road Apples sessions, as was the case with a lot of songs that didn't make it on whatever record. We just never really came back to those songs, but in doing Saskadelphia we thought it should have Montreal. Reformed Baptist Blues is a lot of fun, but Montreal actually has some meaningful traction, I think.

"We found a live version from about 1990, a New Year's Eve gig in Ottawa, but the quality of the tape was a little dodgy. Then I recalled that we played it as an encore at the Bell Centre in Montreal in 2000, the day after the 11th anniversary of the Massacre.

"I had suggested we play Montreal, but everyone said, 'God, we don't even remember how it goes.' Gord didn’t remember the lyrics. Before the encore, someone pulled the lyrics up online. Gord read through, said, 'I remember it,' and we went out and we played for the first time in years."

How has working through this project kept you connected to Gord Downie?

"It's been pretty therapeutic. The best thing about being in a band is that you go through everything together. When the final tour ended we mostly went our separate ways, though we were there for Gord.

"We did have a few writing sessions and recording sessions with him, when he was getting sicker. I don't know what will ever happen to those, maybe nothing. When Gord died, we all went our separate ways; I talk to Sinclair regularly, and Paul and (drummer) Johnny [Fay] occasionally.

The Universal fire lit a spark under me to get in touch with Johnny [Fay]. We're not going out to tour, but there's still stuff to do as a band

"It was the Universal fire that lit a spark under me to get in touch with Johnny, and that started a blaze under Johnny, who is nothing if not dogged. He started the search. He became the band's Indiana Jones, trying to track these tapes down. That was a full year-and-a-half of that for him, trying to get answers from people.

"It did bring us all together; it’s led to weekly Zoom calls. We're not going out to tour, but there's still stuff to do as a band. It’s kept Gord very fresh in our minds; his little brother and his older brother help take care of things as well."

On a similar tangent, what did you glean from the Saskadelphia project in terms of the symbiosis between yours and Paul's playing? How it was back then compared to where it went the further the band went along?

"It's interesting, we never really sat down and had a conversation about, 'I'll do this and you do that.' We just played together a lot and developed a style of working off of each other.

"We evolve as people and musicians. We tried not to repeat ourselves too much. If you've done a lot of the balls-to-the-wall rockers, you need to explore something different. If you've done a lot of blues-y funk numbers, how about changing it up? I'm sure we lost fans along the way, but also gained new ones. It's just what it is."

- Saskadelphia is available now.

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83