The Smiths’ How Soon Is Now? guitar secrets: producer John Porter reveals the exhaustive tonal sculpting behind the alt-rock anthem

The man behind the console goes deep on the creation of one of Johnny Marr and co's most enduring hits

If playing the guitar has taught us anything, it’s that we all make mistakes - and that being open about them and learning from them is the key to our progress.

Back in March, we ran a piece about the tonal secrets of The Smiths How Soon Is Now? - and were pleased when the track’s esteemed producer John Porter got in touch to point out some of our errors!

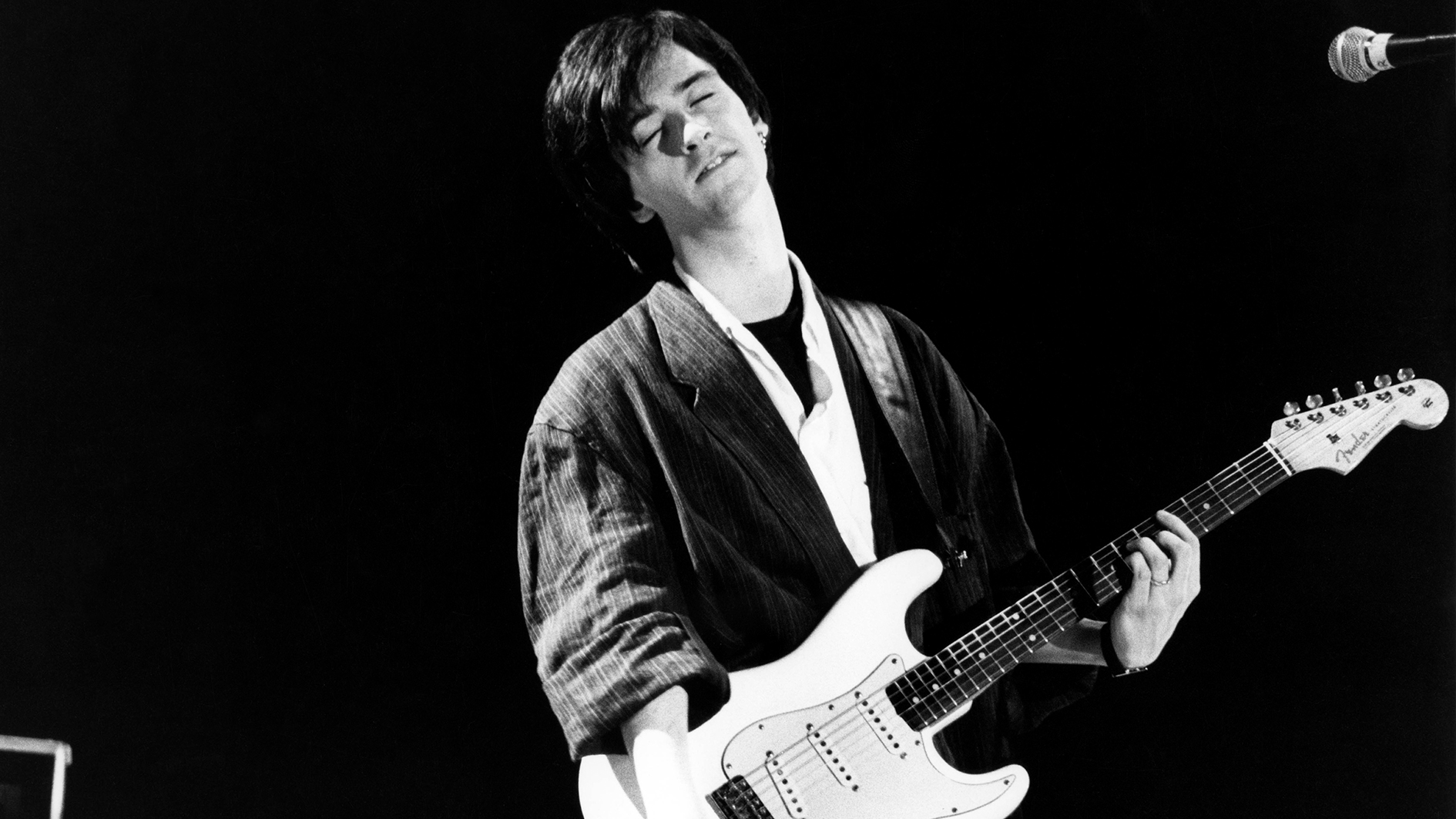

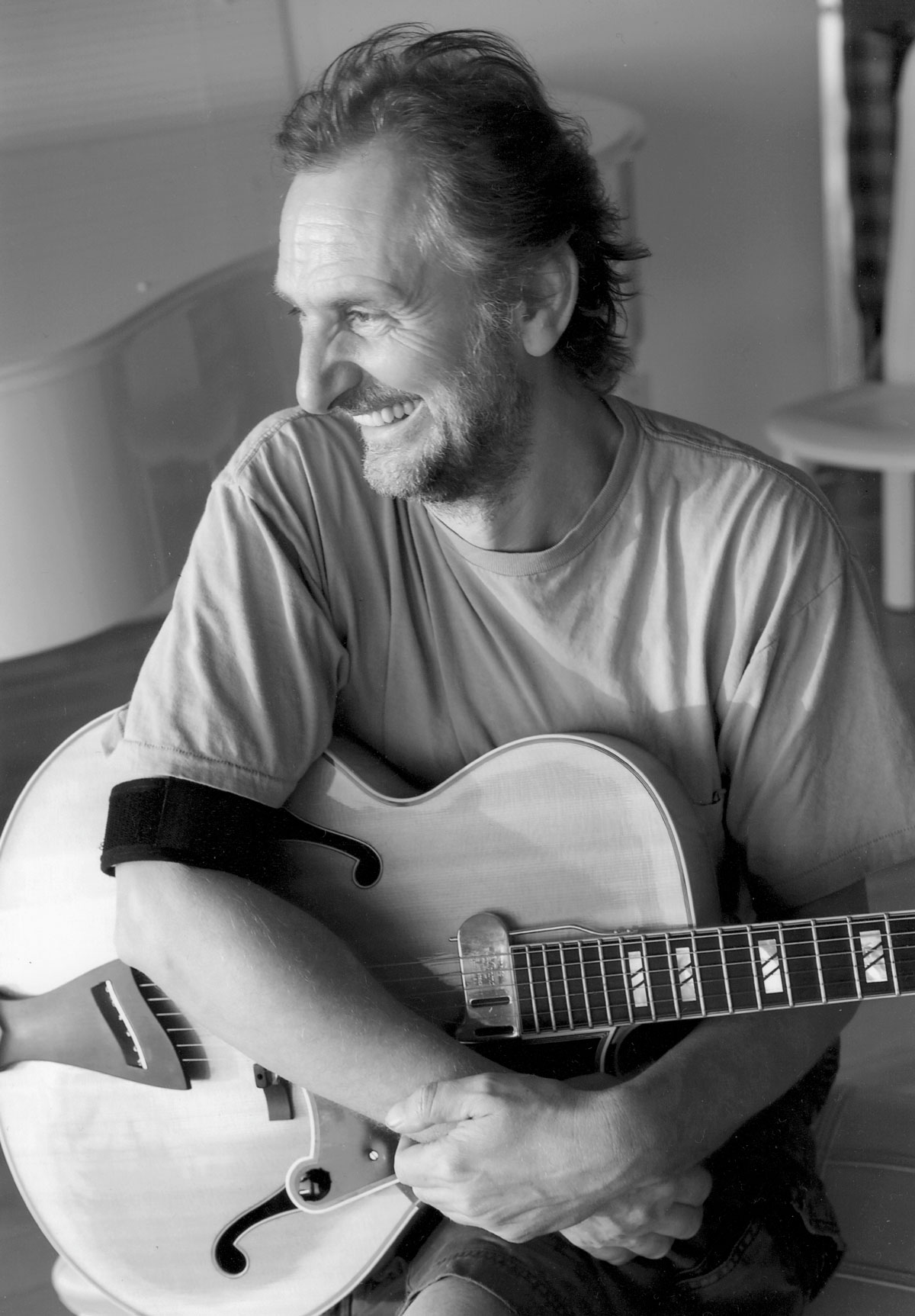

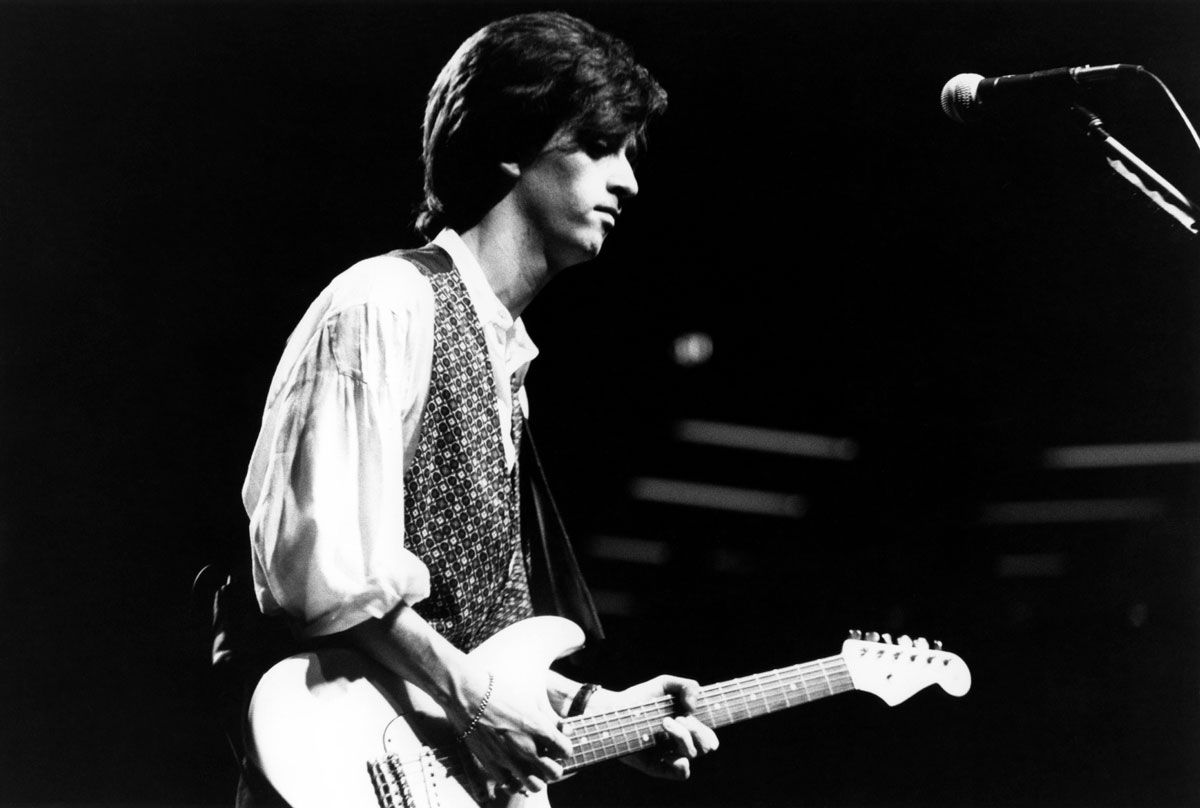

That main rhythm guitar? It was recorded with a combination of a Jazz Chorus and DI (then fed to the famed three/four Twins), via a Drawmer noise gate, while Porter maintains - in contrast to his good friend Johnny Marr’s assertion - that he played the slide part, using his ’54 Tele in open-A tuning, a tweed Fender Deluxe and an outboard UA1176 compressor, along with some harmonizers to get that beguiling train horn sound.

Keen to pick his brain, we asked Porter if he’d like to share some more of his experience in recording and arranging the indie classic. Read on for his detailed account of The Smiths’ most famous studio session, those tones and his thoughts about the song’s legacy.

How did How Soon Is Now first come about?

“We were in JAM Studios [recording William, It Was Really Nothing and Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want]. By that time, we had a good process. Johnny and I had a musical connection, a good short-hand. It didn't take us long to get things into shape.

"We still had another day or two, so I said, 'Well what else you got?’ He played this little lick that was very similar to William, high and kind of fast. Now I had a bit of a bee in my bonnet about this, in that all of their songs tended to have lots of chord changes, whereas I was into black music, James Brown and The Meters and funk bands and the blues, where you'd stay on one chord for hours.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

"So I said, 'OK, let's just have a jam, but stay on one chord.' In those days they used to tune to F#, so they were doing this and it was nice just to hear him playing one chord."

Is that what became the main intro part?

I always took a DI when I recorded because it gives you so much more leeway afterwards

“Yes, but at this stage, there was no 'song'. It was just trying to do something that was a bit different. So I said to Johnny, 'That first lick you were playing, let's take that two octaves down and make it into a B-section. Stay on this one chord for ages, until you get bored of it, and then go into that.'

"So that became the B-section and that is essentially the song. Once we had that, they recorded the sections twice, by which point I thought, 'OK we've got something here.'

“It was all on two-inch tape and Mark Wallis was the engineer - a great engineer - so I then took the master tape and I went through the two takes and I took out all the bits that weren't any good and edited all the bits that were into one thing and that was the basis of the song.

"That point was where the tremolo got introduced. It was like, 'This is kind of cool, but we can make the guitar sound better.' Johnny says different, but I think the initial guitar was into a DI, because I always took a DI when I recorded because it gives you so much more leeway afterwards, and I think we also always used the Roland Jazz Chorus.”

Why did you use the Jazz Chorus as a go-to amp?

“If you needed constant rhythm, just strumming, the Jazz Chorus used to give you this sort of harmonic sound. If you turned it up loud, you could hear things being suggested. We would sort of hear what was suggested by the guitar and say like, 'You hear those two notes coming up?' Let's bring those out and play those on top.'

"So I think the initial guitar was a Jazz Chorus, just doing a stereo Roland Jazz Chorus-thing and a DI. Then I put the Jazz Chorus through this noise gate on the drum and triggered it with a cowbell and that gave us the basis of the tremolo. At some point, we put the DI out through the [Fender] Twins.

"I remember there were three Twins, but Johnny says there were four. One was a blackface, but I also have a vision of a blonde Twin. I don't know why there would be so many Twins unless they were Johnny’s.

"We would hire stuff now and again, but I don't know why we would have hired three or four, but I may have done. My good pal Alan Rogan [best known as Pete Townshend's guitar tech] had lots of great amps and I used to get stuff from Alan and bring it down.”

If you needed constant rhythm, just strumming, the Jazz Chorus used to give you this sort of harmonic sound. If you turned it up loud, you could hear things being suggested

So how did you use the DI signal you sent to the Twins?

"We went out into the studio and I asked Mark to play the track and we would try and chase it with the speed knobs. He had to give us plenty of the Linn drum cowbell in the headphones and we'd try and chase this thing.

"Johnny was doing one and I was doing the other. We would do that until it dropped out and Mark would keep punching us in then stop and saying, 'No, it's gone out.' Then punch in again and we did that until we got a couple of passes and had this sound.

"At some point, I said, 'Let's shore-up the B-section.' I was always into Leslies, so there's a Leslie guitar on slow, playing that. Then this thing had a bit more of a life of its own. All of this stuff was done without any vocals at all. ”

How did the famous slide part come about?

“The song was all on the I but it had these ‘III IV’ chord changes every eight bars or so. Morrissey would never allow backing vocals on Smiths records - I think only one time, maybe, with Kirsty [Maccoll on Ask] - and I thought it was missing out this huge area.

"I started thinking, well, if The Beatles had done this, they would have done some 'oohs' and 'aahs' or something at that point in the song, so I would get Johnny to do a guitar part that would be the equivalent of having a backing vocalist.

“I think I did the slide at that time [Marr has said he thinks he played it], on those III IV chords using a ’54 Tele and an MXR Dyna Comp. I was thinking of The Beatles doing an 'aah'. I think there were two passes because there were two notes and one of them was minor third and one was a major third, so unless you're a monster guitar player, you've got to slide at a huge angle, to change the interval between the two notes.

"I also always had harmonizers going, one up and one down, and so I harmonized on the root note add9 and on the third note, above it, and I think I harmonized something underneath. It was weird, but it sort of worked and then we bounced it all together.”

There are a lot of other textures and minor guitar licks dotted through the track, too. What led to those?

I would get Johnny to do a guitar part that would be the equivalent of having a backing vocalist

"I got Johnny to jam all the way through the track. I said, 'Play something, all the way through. Play a solo' because that wasn't Johnny's thing. So he played and I went through and erased it until there was a bit that I liked and I wound up with these three little half-a-bar licks that were really interesting.

"I took one of them and put it in the AMS [DMX 15-80] - I was a big fan of AMS samplers and the Digital Delay, which you could sample with, so I put this little lick in the AMS and then got Mark to play the track back and I just pressed the button at various points and this little lick came out.

"The other thing we always did was harmonics: we'd find a lick on the harmonics and generally retune the guitar to get the harmonics at [the 12th fret] or wherever and put that down and, possibly, then recorded backwards echo on the harmonics. Then, I think, we all went home! [laughs]”

“Morrissey came in the next day. He had this book of lyrics. We'd put a track up and he'd open it and just start singing… he hadn't written it for the tune or anything, he would just try stuff.

"Quite often, his phrasing was so unconventional anyway that it didn't really make a difference. He found some words that seemed to work and sang it and I think we only did it one time and then he said, 'OK?' at the end and then went off.”

What happened next?

"This was Sunday night, so Mark and I did a mix. It was all on this Harrison desk. It wasn't computerized so Mark and I were all-hands on. Somewhere around halfway, I said, let's have a breakdown, so Mark and I pulled all the drums and the bass down quickly, so it was just the guitar going 'dang-danga-dang', like a re-intro.

"So that was all done on the mix. Then I had all these AMS delays. I was getting a sound on the delay on the guitar and then get a piece of tape to stop the fader going too far, having found the maximum level for it, so I could then flick the fader up to the tape and then pull it back down again.

"I was doing this thing, like 'a shave and a haircut, two bits', the New Orleans [call and response couplet] thing. I was doing that with these four faders, which were just delays, so that was all added to the nonsense and we did the mix.”

What was your reaction to the first mix?

Scott was American, and I, as I said, wanted something that could cross over in America, and he was going, 'Yeah!' But Geoff was giving me this stony look

“I thought, 'This sounds fucking great. This is a breakthrough for The Smiths.’ It must have still been relatively early on the Sunday evening, because I remember I called Geoff Travis up and said, 'You should come down to the studio, we've got something really exciting.'

"I was really buzzed by this, I think Johnny was, too, and Geoff came down with Scott Piering from Rough Trade. I said to Geoff, 'What do you think?' and he looked at me like, 'What's this?' I was kind of enthusiastic and he took the wind out of my sails, completely. Scott, on the other hand, was saying, 'Yeah! This is fucking great, man!' It was this weird thing, where Johnny and I were really jazzed.

"Scott was American, and I, as I said, wanted something that could cross over in America, and he was going, 'Yeah!' But Geoff was giving me this stony look. [Travis maintains he often tried to be impartial in the face of the studio adrenaline]

"The next day, I got a call from Geoff, saying, 'Look, I'll put that track out as a B-side. But Morrissey doesn't like the 'OK' at the end… you'll have to take it out,' which in those days meant I had to completely remix it. It wasn't on recall, it wasn't a computer mix, so I said, 'OK…’”

So where and how did you do the second and final mix?

“I booked in at Eden [Studios] and because it was a computerized desk, an SSL, some of the things that Mark and I had done, I could refine much more. It didn't have to be all in one pass and the breakdown was much easier to do with a computerized desk, because you could mute the drums and the bass with a click, rather than having to whip it all down as quick as you could.

"So I did the mix again. I was quite at home with an SSL - you could plug it all in to be triggered by the dynamics, so lots of stuff was being triggered by the drum. Every time you would hear this particular drum, it would open a gate and send to an echo, which would then go off to a delay. I was setting these incredibly complex chains of stutter at a level that as soon as you could just hear it, that was as loud as I would make it.

"I did the mix and sent it off and, within a week or something, it came out. I thought they were crazy putting this out as a B-side, or I think it was as an extra track or something [as a bonus track on the 12" version of William, It Was Really Nothing].

"I thought they'd wasted it and I was a bit pissed off at Geoff. So it came out as a B-side at one point and then I got the word that they were in the studio with somebody else."

Did Geoff or the band ever explain why you were fired, or rather, not rehired?

If we were in the studio for two days, then most of that time would just be Johnny and me

“He did. He said he thought I was having too much influence on the band and that I was changing their sound too much, which in one sense, to me, was an affirmation that I actually did have something to do with it[s success]! They did get me back in later for a couple of singles. Johnny and I remained close friends. He was like my younger brother, I felt, we were really good pals, so Johnny and I would hang out and he used to tell me what was going on.

"I think he probably called me and said they were going in the studio with somebody else. I think Morrissey didn't like the fact that Johnny and I were so pally. If we were in the studio for two days, then most of that time would just be Johnny and me.

"Once Mike and Andy had done their thing they would go and Morrissey only came to sing. So I was pretty deflated. I thought they'd wasted it. Subsequently it came out again and then it came out again as a single and gradually over the years it became a stand-out thing, you know? But it still sounds good to me. I'm quite surprised at how good it does sound - that guitar sound.”

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

“Around Vulgar, he would get frustrated with me because I couldn’t keep up with what he was doing, guitar-wise – Dime was so far beyond me musically”: Pantera producer Terry Date on how he captured Dimebag Darrell’s lightning in a bottle in the studio

“He ran home and came back with a grocery sack full of old, rusty pedals he had lying around his mom’s house”: Terry Date recalls Dimebag Darrell’s unconventional approach to tone in the studio