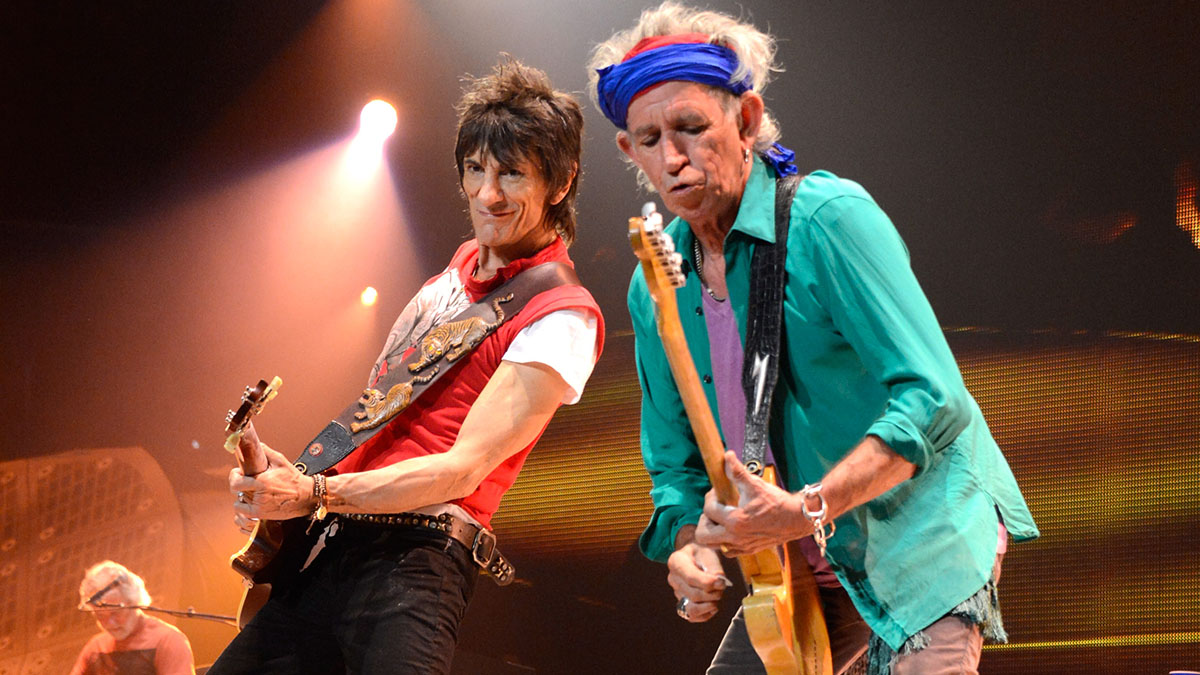

“As soon as I pick up the guitar and play that riff, it’s one of the best feelings in the world. You just jump on the riff and it plays you”: The Rolling Stones’ 10 best guitar riffs

As the Stones return with Hackney Diamonds, we asked you for your favorite riffs from Keith Richards and friends. Here they are – plus the story of how they were created

From 1968 on, The Rolling Stones’ sound was dominated not only by Mick Jagger’s swaggering vocals and the funky rhythm section of Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, but the guitars that somehow sounded unlike anything else out there at the time. Keith Richards had discovered a new rhythm sound, and with it an unprecedented burst of creativity.

Open tunings are common in the world of fingerstyle acoustic and blues slide, but far less so with regular strummed rhythm guitar. But when country-blues legend Ry Cooder showed Richards open G tuning while working with the band during 1968, it was a lightbulb moment for Keith. With this new tuning he would go on to write some of the most memorable riffs of all time.

Tuning the sixth, fifth and first strings down by a tone gives the notes DGDGBD. Keith quickly surmised that having a 5th interval on the bottom string (the bass string) would be a hindrance, so in a moment of genius he simply removed it. This gave a five-string G chord with the root on the bottom, so placing a full barre anywhere on the neck created a new major chord; at the 5th fret we get C, on the 7th fret D, and so on.

When Keith added his second and third fingers to the barre to create what looks like an Am7 shape, the G chord became Cadd9/G, the C became Fadd9/C, the D became Gadd9/D, etc. This simple scheme with its unique sound launched many of the Stones’ greatest riffs.

Here, we list the top 10 – as voted by Total Guitar readers – and reveal the stories of how each of them were written and recorded.

10. Tumbling Dice (1972)

Recorded at Keith Richards’ rented chateau in the South of France, the lead single from Exile On Main Street kicks off with a killer riff in B, played in Keith’s newfound open G tuning with a capo at the 4th fret.

“I was starting to really fix my trademark, starting to find all these other moves,” remembers Richards. “How to make minor chords and suspended chords. The five-string becomes very interesting when you add a capo. It gives a certain ring that can’t be obtained any other way.” As Bill Wyman was absent for the session, lead guitarist Mick Taylor played bass.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

9. (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction (1965)

The riff that broke the Stones globally was ‘dreamt’ by Keith who captured it on his cassette recorder before going back to sleep. In the studio he used a Gibson maestro fuzz pedal to emulate horns, as initially he wanted to replace the guitar figure later.

“I was screaming for more distortion,” he recalled. “We turned the shit up and it still wasn’t right.” Pianist Ian Stewart nipped out to a local music store and returned with the pedal. “I never got into the thing after that,” states Richards, “but it was just the right time for that song.”

Guitarist and founding member Brian Jones played the E-D-A chord figure that goes under the riff on acoustic, Richards added clean electric rhythm, while Bill Wyman walked his bass from root to 4th and back, along the E natural minor scale.

8. Midnight Rambler (1969)

Originally recorded during the Beggars Banquet sessions, Midnight Rambler was held over for the following album Let It Bleed. It was also the final track to feature Brian Jones, who played congas.

Jagger and Richards reckon it’s the archetypal Stones song, written together while on holiday in Italy. Keith said of their four-part epic: “Nobody went in there with the idea of doing a blues opera. That’s just the way it turned out. I think that’s the strength of The Stones; give them a song half raw and they’ll cook it.”

Held together by Keith’s 5th-fret capo boogie rhythm and slide guitars, Jagger adds fills on harmonica while Wyman and Watts groove as only they can.

7. Sympathy For the Devil (1968)

The opening track on Beggars Banquet began life on acoustic guitar with Jagger strumming the chords. “The first time I heard it was when Mick was playing it, and it was fantastic,” Charlie Watts enthused.

Along the way the song transformed into the hypnotic epic we recognise today. As Richards remarked, “It started as sort of a folk song and ended up as a kind of mad samba, with me playing bass and overdubbing the guitar later.”

Although there is strummed rhythm on the final cut from Brian Jones it’s barely audible. Instead the song is propelled by session pianist Nicky Hopkins, with percussion added by members of the band plus Ghanaian musician Rocky Dijon.

The main guitar feature is Keith’s two spiky-toned solos, played on a three-pickup Gibson Les Paul Custom through a Vox AC30. The first enters two and a half minutes in, with spitting E minor pentatonic licks played mostly in shapes one and two. His second outing begins at 4:42, where he elaborates on the gritty, blues-flavoured theme until the track fades.

While Richards’ lead work certainly divides opinion, what cannot be denied is that this instantly recognisable guitar playing powers one of the most important rock songs of all time.

6. Start Me Up (1981)

On any Top 10 Greatest Intros list, Start Me Up should be right up there. But the track, which begins with one of Keith’s greatest ever riffs, had a difficult birth. From when the band first tried it for 1978’s Some Girls sessions (and some have said even earlier), Richards always envisaged it as a reggae number. But after 40 or so takes they shelved the song as a lost cause.

Come 1981’s impending tour, and management demanded a new album. With Mick and Keith not on the best of terms, producer Chris Kimsey trawled the archives knowing he had a clutch of half-finished gems in the can.

Among the failed reggae attempts, Kimsey found a rockier version of Start Me Up that became the basis for the ‘new’ track. As Richards later mused, “With a band that goes on for a long time, you end up with a backlog of really good stuff that you didn’t get the chance to finish, or put out.”

Assembling in New York for overdubs, Keith adopted his trademark Telecaster and open G tuning to nail the three-chord boogie intro. Ronnie doubled it using a harder electric tone and added sparse fills. Jagger’s vocal is classic Stones sleaze, while engineer Barry Sage and Santana percussionist Michael Carabello augment Watts and Wyman’s groove with handclaps and cowbell.

5. Honky Tonk Women (1969)

Another brilliant Keith intro, here he simply picks the open fourth and third strings with thumb and forefinger to create the unforgettable, “Der, dert-dert, der’ lick. With it, Richards stamped Honky Tonk on the world in mere seconds – with a little help from producer Jimmy Miller’s cowbell, Charlie’s kick and snare, and it would seem also from Ry Cooder.

Hired by the band for various projects Cooder has claimed the track is built around licks ‘lifted’ from these sessions.

Honky Tonk can be a bastard to play, man. When it’s right, it’s really right

Keith Richards

“A lot of what I did showed up on Let It Bleed, but they only gave me credit for playing mandolin on one cut,” bemoans Cooder. “Honky Tonk Women is taken from one of my licks.” In his autobiography, Life, Richards admits that Cooder showed him the open G tuning that became his mainstay. Over the years, of course, it has become his own.

Mick Taylor played lead on the track. “I didn’t play the riffs that start it,” he states, “that’s Keith. I played the country-influenced rock licks between the verses.”

We’ll leave the last word to Richards: “Honky Tonk can be a bastard to play, man. When it’s right, it’s really right. There’s something about the starkness of the beginning you really have to have down, and the tempo has to be just right. It’s a challenge, but I love it.”

4. Brown Sugar (1971)

It’s that open G thing again! And on Brown Sugar, which opens 1971’s Sticky Fingers album, it forms the basis of the song’s entire rhythm track. From the opening ‘dit-dit, dat-dat-da-daa-da’ lick, Keith runs around the extended turnaround chords of Eb, C, Ab, Bb, C, with added and pulled-off sus4 and 6th (his classic move).

The verses are built around a modified boogie blues, but with the inimitable sound of Richards’ pile-driving guitars stamping them with pure Stones magic. And when Mick Taylor added fills in the G breakdown section, and Bobby Keys played his belting sax solo, a rock classic was born.

The joyous music, however, is a backdrop to lyrics that were dark and controversial even back in 1971. But 50 years on it was deemed unsuitable to air live, so in 2021 Jagger withdrew it from the band’s setlist, admitting that he would not write such words today.

3. Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1968)

This single from 1968 marked a welcome return from the band’s psychedelic ‘lost weekend’ of Their Satanic Majesties Request to their bluesier, rockier roots. It was also their first time with producer Jimmy Miller, and ushered in a more relaxed and enjoyable way of working – the band had self-produced Satanic Majesties and it had been a long and arduous process.

“I hated it,” remarked Bill Wyman. “Every day at the studio it was a lottery as to who would turn up and what, if any, positive contribution they would make.” Richards, too, found Jimmy’s regime much more enjoyable. “Suddenly, between us, this whole new idea started to blossom, this second wind. And it just became more and more fun.”

Jumpin’ Jack Flash is driven mainly by Keith’s Gibson Hummingbird acoustic tuned to open D with capo added. This was fed into a cassette recorder and back out to a mic’d-up extension speaker. “The band all thought I was mad,” laughed Richards, “and they sort of indulged me. But I heard a sound and Jimmy was onto it immediately.”

Richards added a second acoustic in Nashville tuning (essentially the high octave half of a 12-string set, which gives an almost mandolin-like effect, especially when capo’d). Jones played another rhythm on electric guitar, along with the sparse licks in the choruses.

Jumpin’ Jack Flash is The Stones’ most performed song, and one of Keith’s best-loved. “As soon as I pick up the guitar and play that riff, it’s one of the best feelings in the world,” he grins. “You just jump on the riff and it plays you!”

2. Gimme Shelter (1969)

The track that kicked off Let It Bleed came from a dark place in Richards’ life, but also represented a time of political unrest, race riots, and the Vietnam war. Keith’s problems were that his girlfriend Anita Pallenberg, whom he’d earlier stolen from Brian Jones, was doing risqué scenes with Jagger for the film Performance, and Richards was convinced they’d take things further.

He was also consumed by drug use, and came up with Gimme Shelter while watching people outside a friend’s London apartment rushing to escape from a sudden storm.

Jones doesn’t appear on the track, and Taylor was not yet fully in the band, so Richards played all the guitars. Again it was open G tuning, picking out notes from the descending and ascending C#, B, and A chords, then embellishing them with overdubbed fills.

“That beginning is so eerie, “says Richards. “Sometimes in a stadium you start to hear echoes.” The strumming becomes more insistent as the song progresses, with Keith adding further lead interjections.

Keith also played acoustic on Shelter, but “it died on the very last note,” Richards quipped. “The whole neck fell off. You can hear it on the original take.”

1. Can’t You Hear Me Knocking (1971)

Our poll’s winner is a seven-plus-minute epic of two halves. The first is the ‘song’ part which, unusually for a band that used to jam their tracks into shape, was more or less worked out before they entered the studio. The second section was a Latin-inspired jam that happened purely by accident. More of which later…

The meat and potatoes of Can’t You Hear Me Knocking is Richards’ tight and grungy rhythm track, once again employing the open G, five-string regime and probably played on his black Les Paul Custom. This is countered by a second, equally strident rhythm part performed by Taylor on a walnut brown Gibson ES-345 through a 100-watt Ampeg VT-22 combo amp.

Richards’ part is relatively complex when compared to simpler numbers such as Honky Tonk Women. Using mainly doublestops in 4ths and 3rds, he weaves around the changes while Taylor supports him with a more straight-ahead feel. The two-guitar arrangement works brilliantly to create one of the band’s tightest and most focused pieces of work.

We didn’t even know they were still taping... It was only when we heard the playback that we realised we had two bits of music. There’s the song and there’s the jam

Keith Richards

Unusually for a Stones song, Can’t You Hear Me Knocking features a stack of vocal harmonies. According to Jagger the key was too high and he struggled in places, so layered up his vocals to disguise the crack in his voice on some of the high notes.

The slowly building jam that takes up the majority of the tune is perhaps Mick Taylor’s crowning glory as a Stone. We’ll let him pick up the story: “Towards the end of the song I just felt like carrying on playing” he explains. “Everybody was putting their instruments down, but it sounded good so everybody quickly picked them up again and carried on playing. It just happened, and it was a one-take thing.”

As luck would have it, the tape was still rolling so Taylor’s beautifully toned licks, languid string bends and smooth vibrato (the antithesis of Richards’ spiky leads), were captured in full.

“We didn’t even know they were still taping,” Keith confirms. “We were just rambling and I figured we’d just fade it off. It was only when we heard the playback that we realised we had two bits of music. There’s the song and there’s the jam.”

Listening to the finished article, on which Bobby Keys added a gritty tenor sax solo, Billy Preston provided organ stabs, and Rocky Dijon and producer Jimmy Miller chimed in with congas and other percussion, it’s clear that Richards was giving Mick Taylor his moment.

Having no idea that they were being recorded, the confidence and class of the core members is evident throughout, while Miller’s idea to augment the jam with other musicians was a masterstroke.

Many cite Mick Taylor’s tenure with The Rolling Stones as the band’s most musical period, and listening to this it’s hard to deny. Taylor, however, is more modest about his contribution.

“I tried to bring my own distinctive sound and style to Sticky Fingers, and I like to think I added some extra spice,” he speculated. “I don’t want to say ‘sophistication’ – I think that sounds pretentious. Charlie said I brought ‘finesse.’ That’s a better word, so I’ll go with what Charlie said.”

In the late '70s and early '80s Neville worked for Selmer/Norlin as one of Gibson's UK guitar repairers, before joining CBS/Fender in the same role. He then moved to the fledgling Guitarist magazine as staff writer, rising to editor in 1986. He remained editor for 14 years before launching and editing Guitar Techniques magazine. Although now semi-retired he still works for both magazines. Neville has been a member of Marty Wilde's 'Wildcats' since 1983, and recorded his own album, The Blues Headlines, in 2019.