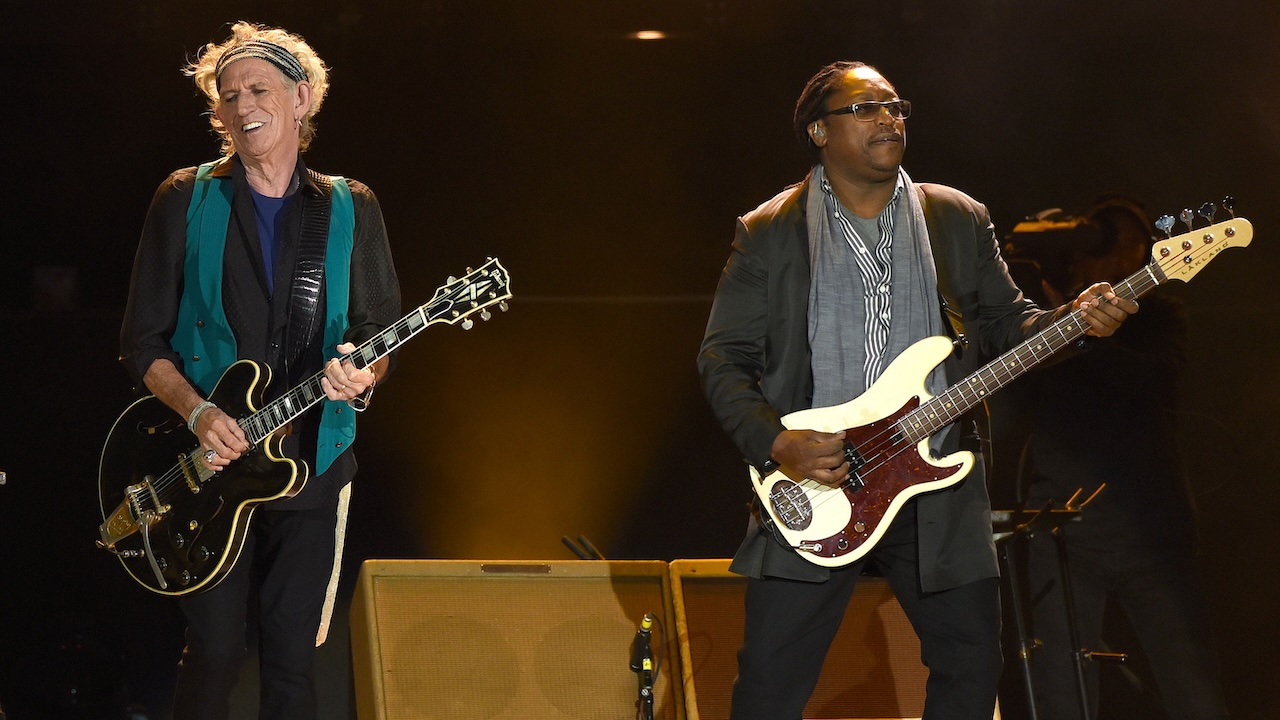

“The Rolling Stones gig is the culmination of my childhood dreams – I figure now that I've played with Miles, Sting, Herbie Hancock, Peter Gabriel, and Madonna, I've pretty much covered it”: Darryl Jones looks back at the path that led him to the very top

The Rolling Stones bassist is a force of nature, with a stage and session career second to none

Darryl Jones: jazz cat or rock star? Some pigeonhole the 62-year-old as a jazz cat, most likely because his first big professional gig was with Miles Davis in 1983. Others say rock star, because for the past 30 years, he's held down the bass chair with the Rolling Stones.

Jones doesn't even know the answer himself. “I straddle the fence,” he told Bass Player. “Once I was playing with Miles at a festival with the Modern Jazz Quartet, and one of those guys came up to me and said, ‘I really don't like rock music, but I like the way you play rock.’

“Another time, I was recording with guitarist Carlos Alomar, who had played with David Bowie for a long time, and the guys at the session were all rock guys. At the end of the session, one of them came up to me and said, 'Listen, man, I don't dig jazz, but I like the way you play jazz.’

“In a way, I've been this wandering musician, moving from one idiom to the other, and I've been influenced by all the people I've worked with.”

And Jones has worked with a lot of people. Over the last 30-plus years, the Chicago-born bassist has graced the stage or the studio with Sting, Madonna, Peter Gabriel, and Eric Clapton, among others. But the whole rock-star thing truly took root in 1993, when he replaced Bill Wyman in the Rolling Stones.

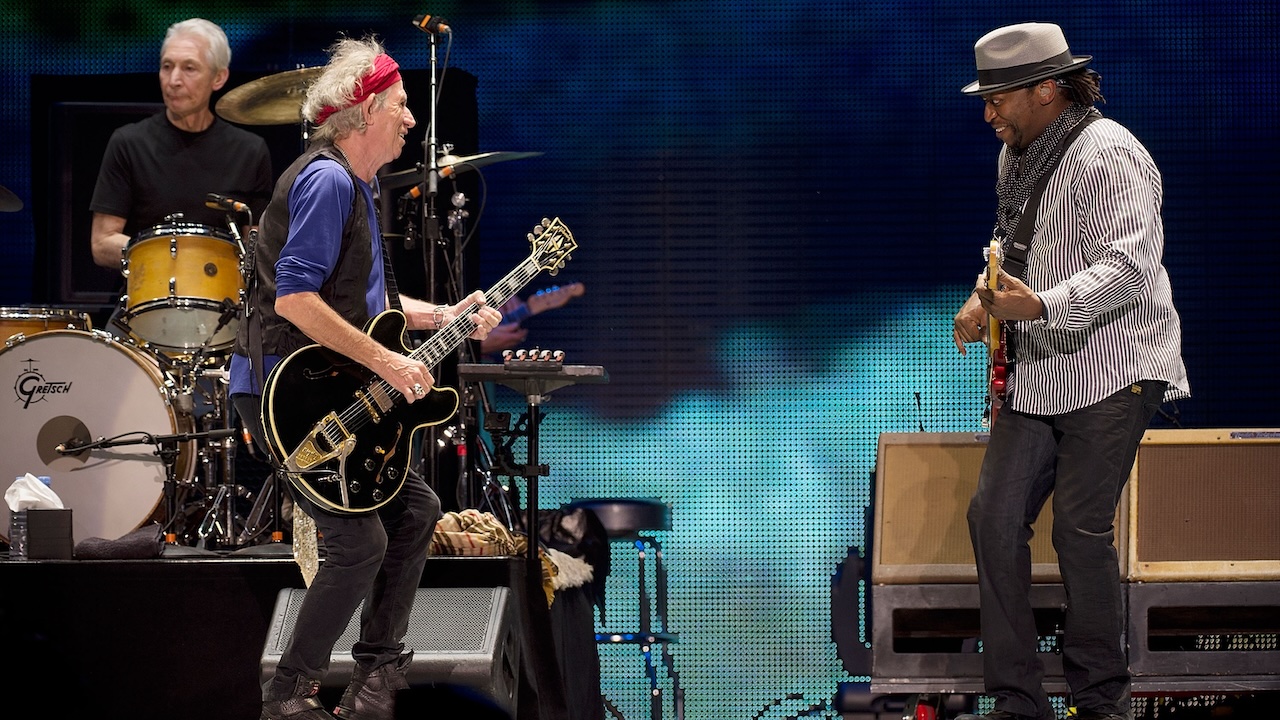

Back in August 2005, in the midst of preparations for the Stones' four-month cross-country trek for the A Bigger Bang tour, the dreadlocked, baritone-voiced bassman took time out to reflect on his career.

What is the Rolling Stones groove, and how do you make it happen?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“It's a rhythm & blues pocket, but it's a little looser. That took a little getting used to for me. I remember in the beginning, sometimes when Charlie Watts would go from section A to section B of a tune, it would feel like the pocket was starting to stretch during some of his fills, and I would make an adjustment.

“But I noticed when I made that adjustment, I would end up in a place where I didn't want to end up, because the pocket hadn't moved as much as I thought it had. Now I solidify it, but I don't lock it up so tight that it can't breathe. I always have a great time playing with those guys. It's lots of fun.”

Can you talk about the Rolling Stones' compositional process?

“The first thing that happens is Mick and Keith get together and throw around different riffs and ideas. Keith once told me that sometimes he'll play an old tune on piano, like something by Hoagy Carmichael, or a blues tune, and his hands will fall to different places. That's how he'll come up with a song. Then Charlie comes in and they start adding people.

“Recently, I've discussed basslines with Mick more than l ever have, because he has a better idea of what he's looking for. Then we'll try a bunch of different stuff. We'll try straight eighths, we'll try a full-blown line, we'll try doubling the guitar – until we come up with something he's satisfied with.

“Keith is much more hands-off. He just puts the idea out there and lets you develop it in a way that's more organic to you. The interesting thing about Keith's writing is that I know a bit about the way he plays bass guitar, so now I have a repertoire of things Keith will do to make the bassline his, to give it those ‘Keith’ characteristics. Like, instead of playing the root note, he'll play a 3rd lower. I try to add those things to their writing to try and make it a little more Stones-ish.”

You've played in venues of all shapes and sizes, and now you're headed out on another arena tour. What do you do differently at a small place like the Jazz Bakery in Los Angeles, versus a stadium like Chicago's Soldier Field?

“It all depends on the song. If it's a mellower tune, I'll use the same touch at the Jazz Bakery as I would at Soldier Field. If I'm playing something that's really hard-rocking in a large stadium, I'm going to touch the bass a different way.

“I tend to use more of a ‘monkey grip’ when I'm playing rock, because I don't have to get to as many notes as I would if I were playing some kind of bebop lick. Grabbing the bass around the neck facilitates a different kind of feeling. I'm not trying to do anything real intricate. I'm only using the amount of technique necessary for me to play a particular song. So the song dictates my approach.”

When you first started playing, did you ever envision yourself onstage at Soldier Field?

“Actually, I did. In the early '70s, before I started playing bass, my mom took me, my brother, and a couple of kids from around the neighbourhood to see James Brown at Soldier Field, and it got to be a real dream of mine to play there.”

“In a way, the Rolling Stones gig is the culmination of those childhood dreams; I figure now that I've played with Miles, Sting, Herbie Hancock, Peter Gabriel, and Madonna, I've pretty much covered it.”

What is it about you that's attracted such a disparate batch of musicians?

“A few years ago, a friend from my neighbourhood said to me, ‘You realize that part of the reason you play music the way you do is that you came from a two-radio home.’ When I asked him what he meant, he said, ‘I know your mom was listening to James Brown and the Temptations and all that stuff on Chicago soul station WVON.’ Ironically, every once in a while you'd hear a Stones song like Angie or Satisfaction on WVON, but it was basically all black music.

“My friend also noted that my dad always listened to jazz on WBEE and public radio, and he played his Count Basie, and Oscar Peterson records. So I have elements of the Motown thing in my playing, but there are also things I got from Stanley Clarke and Anthony Jackson. I also dug Ray Brown. I didn't necessarily get stylistic stuff from him; it was more in terms of the groove.”

“I didn't study any of these players – they just found their way into my blood. So that's probably why I was able to move from one to the other. Like with Sting: that music wasn't run-of-the-mill rock 'n' roll, nor was it run-of-the-mill jazz, and I was able to provide a solidifying force.”

Do you have any tips on how a young musician could go about landing a job with a higher-profile artist?

"When I talk to a young bass player about this kind of thing, it usually starts with them telling me how they're frustrated with their musical situation, whether it be a high school band, a college band, or a bar band. They'll tell me they want to do something more, to play with musicians of a higher caliber.

“I tell them that before they get on a great gig with a bunch of great musicians, the person who's going to give you that gig is going to see you at a bar playing with a drummer you don't dig playing with. So you've got to figure out a way to make that work, because that's part of your entrée into the new gig.”

“Second, be specific about what kind of music you're interested in playing, and whom you'd like to play with. Pick three or four bands that you really, really want to play with, familiarize yourself with their music, and try to familiarise yourself with their management. You want to do everything in your power to make it easy for the person who's in charge of hiring the musicians – be it the drummer, the manager, or whoever – to think of you when they need a bass player.

“First, you go to the band's concerts and if possible, you meet some of the band. But if that's not possible, you still have to do as much as you can for yourself, like going and learning the music. You make your own luck by being prepared.”

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

“One of the guys said, ‘Joni, there’s this weird bass player in Florida, you’d probably like him’”: How Joni Mitchell formed an unlikely partnership with Jaco Pastorius