“Forget grunge music. Get a pint of Guinness down your neck and pick that guitar up”: The rise and fall of Britpop, the Nineties’ other massive guitar movement

The UK got its guitar mojo back in the ’90s with a new generation of rock and indie bands. This is the story of how it all got consumed by the rivalry between Blur and Oasis, and the catch-all category of Britpop

For the 90,000 screaming fans on their feet at London’s Wembley Stadium this past July, it must have seemed like it was the spring of 1994 all over again.

Back then, Blur had just blown up on the back of the disco-ish, new wavey hit Girls & Boys, the first single from their third album, Parklife, and it looked like they were going to lead their countrymates through an exciting international scene that steered around the boilerplate alt-rock sounds of the day and paid tribute to some of the greatest bands in the history of British rock.

Deemed the pioneers of Britpop, Blur spoke for a generation of British youth – at least for a while. Their guitarist, Graham Coxon, was one of the most skilled and innovative players on the scene, and frontman Damon Albarn was one of the most charismatic and quintessentially English vocalists, singing every line in an accent stronger than a keg of Fuller’s Golden Pride.

Gloriously incestuous, the scene flourished on connections. Albarn’s muse and romantic partner was Justine Frischmann, the co-founder of (the London) Suede and the future frontwoman of Elastica. For her, Suede, Oasis, Pulp and other emerging U.K. bands, the coming years would be as wild as the crowd at the World Cup finals and as regal and majestic as the Union Jack flapping in the breeze.

Blur’s two Wembley shows marked the largest audience the band had ever played for. Those immersed in the euphoria enjoyed a stunning flashback of Britpop history, back when Blur were on the top of the U.K. charts and making inroads in the rest of the world. Back before a bunch of arrogant, rude Mancunians who called themselves Oasis would release albums full of songs that upended Blur as the champions of working-class Britpop.

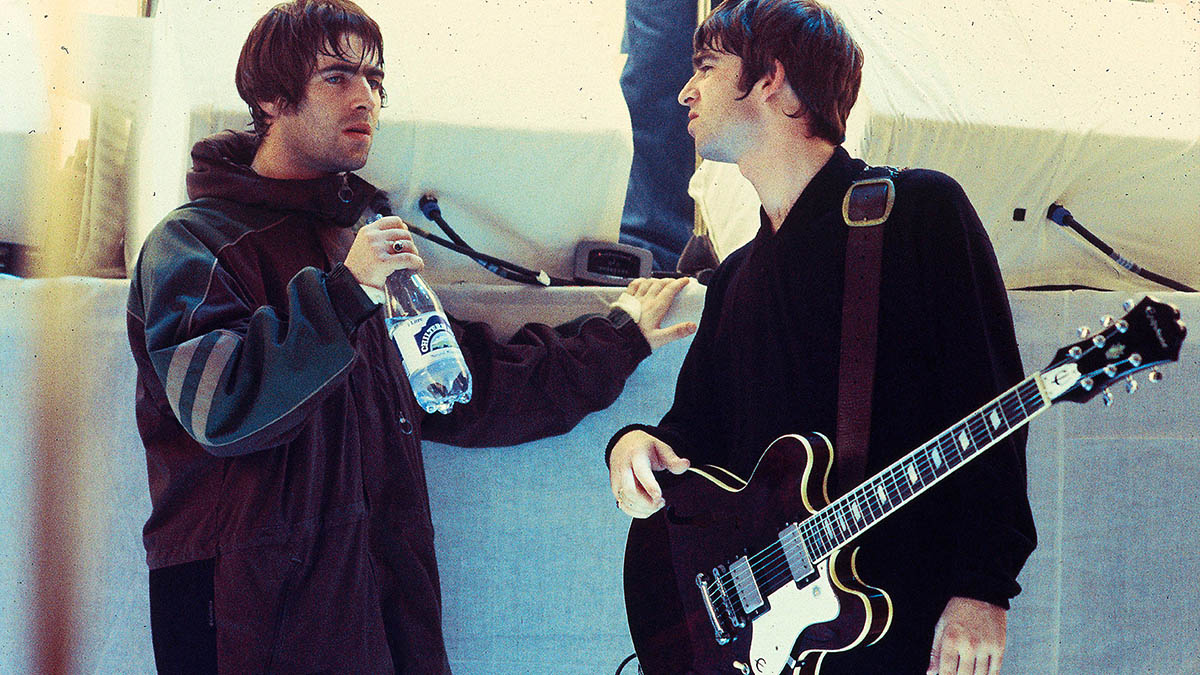

Today, Oasis are no longer a threat, and England, at least for the time being, has taken Blur back under its wing. During the Wembley shows, the band played hit after hit from their nine-album career while the Oasis brothers, Noel and Liam Gallagher remained distanced from their former rivals, carrying on with their respective solo projects and enjoying their celeb lifestyles.

Judging strictly from the audience’s ecstatic reaction to Girls & Boys, Parklife, The Universal and Song 2, it’s hard to imagine that Oasis could recapture this much adoration from the British public… Of course, stranger things have happened – like back in April 1994 when Oasis left the nation slack-jawed, popping out of nowhere with their first chart single, the chemically euphoric and Stones-ish Supersonic.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Or when Oasis released the fourth single from their second album (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, Wonderwall, a sparse, infectious number that became a worldwide smash and turned Oasis into kingpins of Britpop, making Blur seem somewhat disingenuous by comparison.

Structured after, and primarily influenced by the British Invasion, the ’90s Britpop movement wasn’t nearly as monumental as the ’60s revolution that spawned it. But for about a decade, it was a high point in English music and spawned a generation of enthusiastic players and songwriters turned off by the dominance of American music in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“If punk was about getting rid of hippies, then I’m getting rid of grunge!” Albarn told the NME. “It’s the same sort of feeling: people should smarten up, be a bit more energetic. They’re walking around like hippies again – they’re stooped, they’ve got greasy hair, there’s no difference.”

Forget grunge music. Get a pint of Guinness down your neck and pick that guitar up

Noel Gallagher

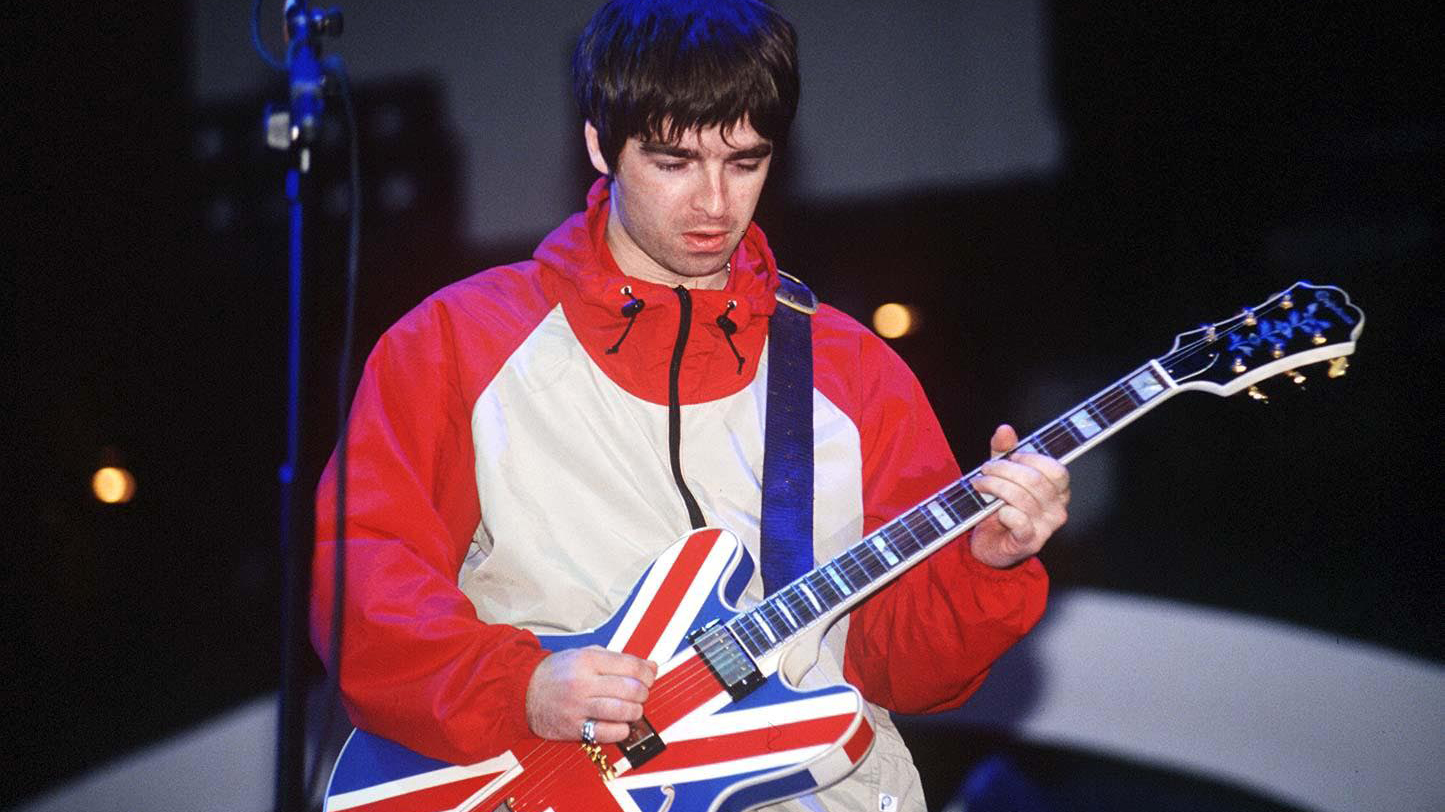

Oasis guitarist Noel Gallagher also lashed out at the aggression and negativity of alt-rock, crafting highly melodic songs, many rooted in open chords. By the time they released their first album, Definitely Maybe, in 1993, Oasis were press darlings and poster children for cockney lads who blew off steam by forming bands with their friends, hanging out in the pub, getting in skirmishes with rival gangs and popping ecstasy by the handful.

“We were the first people to come out and say, “The world’s a great place, life is for living!” Gallagher told Billboard. “Forget grunge music. Get a pint of Guinness down your neck and pick that guitar up.”

Led by Blur and Oasis, the Britpop scene exploded in the U.K. in the early ’90s and soon included a sonically diverse collection of acts, including the aforementioned groups as well as Supergrass, Ocean Colour Scene, Gene, Cast, Sleeper, the Bluetones and Echobelly.

Each of the Britpop bands had their own sound, but they all turned to classic British groups in an effort to stray from the downcast, testosterone-fueled vibe of grunge and alt-rock.

“From punk onwards, every generation of artists spent their entire time trashing the monuments of the ’60s,” Gallagher said in Daniel Rachel’s Don’t Look Back in Anger. “They didn’t want anything to do with it. What my generation did was rebuild the monuments of the ’60s because the ’80s didn’t mean a great deal to us. We reinvented the Beatles.”

As with almost every band inspired by British rock, the cornerstones of Britpop were the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. But there were other mainstays. Blur were influenced by the Kinks and art-pop bands like XTC; the La’s resembled the Hollies; the London Suede aped David Bowie; Ocean Colour Scene loved the Small Faces; the Bluetones mirrored Squeeze; Elastica sounded a lot like the Stranglers; Gene and Echobelly resembled the Smiths; and Cast and Supergrass were reminiscent, in their own ways, of the Who.

“It occurred to us that Nirvana were out there, and people were very interested in American music, and there should be some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness,” Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann said in The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock by John Harris.

“It was a time when it literally felt cool to be British,” Echobelly guitarist Glenn Johansson added in Don’t Look Back in Anger. “Especially in relation to the creativity that seemed to be pouring out of the country at that time.”

Not every burgeoning English band went along for the carnivalesque Britpop ride or eagerly toured with other groups from the scene. When Radiohead released their second album, The Bends, in 1995, some lazy journalists lumped them in with Britpop, ignoring the skewed offbeat artistry of songs like My Iron Lung and Planet Telex. Radiohead loathed being pigeonholed, and they weren’t too fond of Britpop.

“To us, Britpop was just a 1960s revival,” guitarist Jonny Greenwood told Rolling Stone. “It just leads to pastiche. It’s you wishing it was another era. But as soon as you go down that route, you might as well be a Dixieland jazz band, really.”

For Blur’s Coxon, the experimentation and noise of American indie bands like Pavement and Dinosaur Jr. was as exciting as music by his English heroes. Also, it was less homogenous and predictable than the song structures of other Britpop bands.

“Talking as a guitar player, Britpop for me was fucking really dull,” Coxon told The Guardian. “No one was doing anything interesting with a guitar. They’re all jolly nice and totally good on their instruments, but it became a thing…

“For me, people like Sonic Youth, Bikini Kill, Pavement and other small-label punk groups from America – these kids were teenagers. They were playing like they didn’t give a shit and like their life depended on it. That’s why I got so upset [about being typecast in a Britpop band]. …the Melvins and the Wipers, and these bands are brilliant unsung heroes, really.”

But while he loved the ramshackle quality of indie rock, Coxon also admired unconventional and creative guitarists from the British Invasion, including Dave Davies and Pete Townshend. Also hugely influential to Britpop songwriters: Deep Purple, the Smiths, the Jam, the Clash, the Cure, New Order and, in a big way, the ’90s rave scene in Manchester.

Nicknamed Madchester due to the abundance of drugs and alcohol consumed and the insanity that prevailed, bands including the Happy Mondays, the Charlatans UK, Inspiral Carpets and the Stone Roses provided an inspiring soundtrack to the all-night revelry. Blur even appropriated the Roses’ ’60s psychedelic vibe and loose backbeat groove on two commercial hits from 1991’s Leisure, She’s So High and There’s No Other Way.

“When Blur first started and we were playing Manchester, the Haçienda [a club co-owned by members of New Order] was the place to go,” Coxon told Designer magazine. “That was where a lot of exciting stuff was happening, and London was pretty dead.”

Gallagher reached for the stars in the same venues. Before he joined Oasis, he was a guitar tech for the Inspiral Carpets. “I was at the Haçienda from its early days and at all the big raves,” Gallagher said in Don’t Look Back in Anger. It gives me shivers when I think about it. That’s all wrapped up in being young and not being famous and just being carefree and high on ecstasy and dancing in a field at fucking 2 in the afternoon.”

Britpop took off in England almost as fast as a souped-up Triumph Stag down an empty motorway. Blur went gold with Leisure, Suede (which became the London Suede in the U.S. since an East Coast singer-songwriter trademarked the name years earlier) hit Number 1 in the U.K. in 1993 with their eponymous album, and Oasis’ Definitely Maybe sold 100,000 copies in its first four days of sale in the U.K., easily topping that week’s chart.

In the U.S., Britpop was a slower burn. Indie magazines like Alternative Press and Ray Gun, as well as MTV’s alt-rock show 120 Minutes covered the movement since the dawn of Blur and contributed to the early ’90s recognition of Pulp, the London Suede and the Verve.

But the scene didn’t become mainstream until Oasis stormed the castle with a batch of simple, melodic pop songs that swaggered like Jagger and glistened with ’tude.

Before that, two factors prevented Britpop bands from breaking America as the Fab Four had done decades before. Having never played outside of Europe, Britpop bands mistakenly thought they could become rock stars in the U.S. after one or two tours of major cities.

More significantly, the way many bands flaunted British culture and acted (singing in heavy English accents, badmouthing American rock and raising the Union Jack at every photo op) was a major turn-off to grunge-loving Americans.

“That whole anti-American, ‘Yanks go home’ thing – a lot of those bands weren’t really successful in America,” Lush guitarist and vocalist Miki Berenyi told Vice (Lush started out as part of the ethereal shoegaze scene before gravitating toward Britpop). “It felt a bit sour grapes,” she continued. “Like, ‘We don’t want to be big in America because it’s shit, we’re big in Britain.’ Then suddenly they get a bit big in America and it’s like, ‘We’ve conquered it.’ Fuck off.”

Not surprisingly, U.K. bands trumpeting their British-ness was a major selling point for English audiences. Suddenly, Blur, Oasis, the London Suede, Pulp and others were celebrating working-class England.

Nothing epitomized this tell-it-like-it-is scenario like Pulp’s Common People, in which an upper-crust college student romanticizes the English squatting lifestyle and hooks up with an impoverished bloke to see how glamorous it is to be poor.

In the song the student says, “I wanna live like common people/I wanna do whatever common people do/Wanna sleep with common people,” to which he replies, “Pretend you’ve got no money/… Smoke some fags and play some pool/ Pretend you never went to school.”

Britpop was empowering for common people who lived paycheck to paycheck. And with so many English musicians lacking a college degree, it wasn’t a huge stretch for them to write about their ordinary lives and their aching desire to escape their hometown and make something of themselves.

“When I learnt to play the guitar and started to write songs and joined Oasis, I remember thinking, I’ve got one chance,” guitarist and songwriter Noel Gallagher told Don’t Look Back in Anger. “It wasn’t about Britpop. I thought, ‘I have one chance to make some fucking money’; just not to be fucking poor, and to see the world. That was it. I come from a family of grafters. And you don’t get anything by not working, [so] I did it all the time, every day.”

I come from a family of grafters. And you don’t get anything by not working

Noel Gallagher

Blur’s evolution into storytellers for the working class was more reactionary. Albarn came from a solid middle class family. When the band returned from their 1991 44-date U.S. tour to support Leisure, they were so dispirited by how awkward and misunderstood they felt that they nearly broke up.

Albarn was especially distraught and sought solace in English culture. He developed an especially strong appreciation for the Kinks’ approach to storytelling. “[Ray Davies] was very near my idea of perfection in songwriting, who carried it off with an immense amount of dignity,” Albarn told the NME.

After a bit of soul-searching, Albarn wrote a batch of songs about the British working class and the little victories they found in their daily lives. He based his lyrics on the white Anglo-Saxon families he encountered after his family moved from progressive, ethnically diverse, Leytonstone, East London, to the small town of Colchester 50 miles away.

“Those characters were my bedrock – the good yeomen of the fair county of Essex – people I watched and observed and lived among, and who then populated my songs for many years,” he told Don’t Look Back in Anger.

As with other music scenes, once enough bands became popular enough in the U.K. for the masses to notice, a rivalry developed between two top dogs. In this case, it was Blur and Oasis, and record companies and magazines exploited the friction between the two as an opportunity to make lots of money.

The press baited both bands and, while neither had especially kind things to say about the other, Oasis were particularly vicious. Blur may have claimed Oasis were simplistic and derivative, but the Gallagher brothers smack-talked Blur with plenty of F-bombs and ultimately accused them of being elitist, inauthentic art-school hypocrites who, nonetheless, claimed to represent the British working class.

Coxon insists he never hated Oasis (despite his distaste for Britpop) and found the battle of the bands to be unnerving and unnecessary. However, he claims he understood how, in a high-stakes game of ’90s pop superstardom, the rivalry was inevitable.

“If you throw a bunch of competitive young men into the ring and all they have is music… the single door that might lead to them becoming rich and famous, then of course they’re going to stand their ground, get ratty and act territorially,” Coxon wrote in his autobiography, Verse, Chorus, Monster!

The friction between Blur and Oasis hit critical mass in 1995. Blur’s fourth album, The Great Escape, came out on September 11, 1995, and Oasis released the follow-up to Definitely Maybe – (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? – on October 2 that same year.

To create pre-release hype, Oasis’ first single for the album, Roll with It was scheduled for April 24, one week before Blur’s Country House. So, to encourage discord, Blur’s record company moved the release date back a week, which became national news.

The Blur vs. Oasis battle wasn’t so much about the songs as what the groups represented. Blur came from the South of England, an affluent, educated area, and all of the members were articulate and comfortably middle class.

By contrast, Oasis were from the North, where families crowded into council homes, worked in factories and sometimes never ventured beyond the borders of their hometown. Neither of the Gallagher brothers went to college and their accents were so strong, they made Blur’s accents seem like BBC broadcasters by comparison.

Country House sold 274,000 copies and Roll with It sold 216,000, earning Blur the victory and the invitation to perform on that week’s Top of the Pops TV program. But while Blur won the battle, they lost the war. It didn’t matter that none of the members grew up wealthy; in the fight between the classes, they were widely perceived as artsy, privileged college boys and Oasis were embraced as true working-class heroes.

“The weird thing was the casting of myself, and us as a band, as these public schoolboys,” Albarn told Don’t Look Back in Anger. “Noel identified a very unprotected part in the armor and very effectively stuck his sword in there. I went, ‘Ow, that really hurt.’ ”

While Blur hardly fell into obscurity with The Great Escape, which entered the U.K. charts at Number 1 despite the controversy, it was Oasis that rocketed to multi-platinum stardom.

Of course, the fact that (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? was filled with slightly melancholy, easily accessible guitar-pop hits like Wonderwall, Champagne Supernova, Some Might Say and Don’t Look Back in Anger legitimized Oasis’ success. By comparison, Blur, like their influences, wrote more complex, eclectic songs; they were never a hit factory.

A great song is indestructible. It can survive anything you throw at it – even the terrible video didn’t kill Wonderwall

Jarvis Cocker

“I couldn’t write something like Wonderwall, ” Albarn told the NME. “I just can’t bring myself to write simple stuff like that. Why on earth would I want to?”

“ Don’t Look Back in Anger was when I realized Oasis were the ones who had made that journey from being alternative to being a part of everyday life,” Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker said in Don’t Look Back in Anger.

“Every single bar seemed to be playing it. They’d done that thing that everybody had been trying to do of making that connection with the mass public. Wonderwall had been a massive hit, but Don’t Look Back in Anger was like a done deal. It has a tune that instantly sets it apart. A great song is indestructible. It can survive anything you throw at it – even the terrible video didn’t kill it.”

Ironically, Oasis set the bar so high with (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? that they couldn’t top themselves, let alone match their greatest achievement. Not that they didn’t try. For their follow-up, 1997’s Be Here Now, they pulled out all the stops, recording in numerous studios, including Abbey Road, and layering songs with horns, strings and multiple guitar overdubs.

They seemed to have forgotten that it was simple, catchy songs that won over audiences, not grandiose arrangements and overinflated production. Even so, the album entered the U.K. charts at Number 1 and sold almost 1.5 million copies in England alone. Today it is seven times platinum in the U.K. and platinum in the U.S. Even so, it was the band’s last platinum release, and looking back at Oasis’ career, Noel considers it to be the band’s low point.

“I know where we lost it,” he told Q magazine. “Down the drug dealer’s fuckin’ front room is where we lost it. If you’re given a blank check to record an album and as much studio time as you want, you’re hardly gonna be focused.”

As much of a blow as Be Here Now was to Noel, he and Liam kept the band going with a revised lineup (including Ride’s Andy Bell) and in 2000 released the electronic-embellished psychedelic record Standing on the Shoulder of Giants with a slightly different lineup. The record went double platinum in England, where it topped the charts, but was the band’s first album not to go gold in the U.S. Oasis followed with three more albums, including their swansong, 2008’s Dig Out Your Soul.

Meanwhile, after The Great Escape and the Britpop war that followed, Blur shifted directions, integrating more elements of American indie rock into their sound, which yielded them their most popular song in the U.S., Song 2, the distortion-drenched main riff of which sounds like a satire of American aggression.

Ultimately, it wasn’t the missteps by Oasis or the musical about-face from Blur that killed Britpop. That had more to do with the way everyone from runway models to politicians exploited it to gain favor with the masses.

Tony Blair, the youngest English prime minister since 1812, hobnobbed with Oasis and trumpeted Britpop as a symbol of a newer, hipper Britain. The term Britpop was replaced by the more nationalistic slogan Cool Britannia. It was a loaded term, one that some argue was the first step toward Brexit.

The media’s adulation for all things British led to a climate of intolerance and “lad culture” that yielded an increase in misogyny, racism and homophobia. When many British people looked back at the aftermath of Cool Britannia they didn’t like what they saw, and many Britpop bands recoiled in horror at what they had inadvertently helped cultivate.

“I think like all movements it started off with good intentions,” Cocker said in While We Were Getting High. “When we were writing those songs in 1991 it felt thrilling and against the grain, but what began as a frank documentation of life as a poor, white, marginal man living in rented rooms in London – and which was in broader terms an exciting rejection of American cultural imperialism – soon became a jingoistic, beery cartoon when the money moved in.”

The death knell for Britpop came with music that took some of the English pride of Blur, Oasis, Pulp and others, and codified it into a more commercial, palatable form of entertainment: Enter the Spice Girls.

When singers and dancers Geri Haliwell, Victoria Adams (now Beckham), Melanie Brown, Emma Bunton and Melanie Chisholm burst onto the English scene in 1996, screaming “Girl Power!” a new generation of happy, kid-friendly cartoon revelry took over, and the mass media dismissed Britpop as callously as it previously wrote off hair metal.

The next obvious step was the resurrection of teen pop. As the Backstreet Boys, NSYNC, Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera and others took over the mainstream, a few English rock groups influenced by classic songwriting continued to draw large audiences, including Coldplay, Muse and Keane, but Britpop was effectively over.

On August 28, 2009, Noel Gallagher disbanded Oasis due to irreconcilable differences. “It is with some sadness and great relief that I quit Oasis tonight,” read his statement. “People will write and say what they like, but I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer.”

Liam started the new band Beady Eye, with whom he recorded two albums, then he went solo and has released three albums to date, the most recent of which, C’Mon You Know, came out in May 2022 and hit Number 16 on the U.K. charts. Meanwhile, Noel launched Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds, who have released three studio albums, including Council Skies, which came out June and peaked at Number 20 in the U.K.

Blur fell apart before recording 2003’s underwhelming Think Tank, which didn’t include Coxon, and broke up shortly after. They reunited with Coxon in 2015 and recorded The Magic Whip, which debuted at Number 1 in the U.K. (Blur’s sixth album to do so) and Number 24 in the U.S. In late July, Blur released The Ballad of Darren, a blend of American and British rock styles that span the band’s career.

None of the above put Britpop back on the map, and despite Blur’s triumphant Wembley shows, there’s not likely to be a full-scale resurgence of the genre. Still, several bands have come back for a second go-round. Pulp re-formed this summer for U.K. shows but have no plans to enter the studio.

Cocker’s last release was his 2021 solo album, Chansons d’Ennui Tip-Top, a collection of 12 French cover songs. Suede remain active and recently played a 12-date tour in the U.S. to support their ninth album, 2022’s Autofiction, which debuted at Number 2 in the U.K. (their highest slot since 1999) but failed to chart in the U.S.

A big Britpop package tour – or a bunch of small reunion tours – would be exciting and nostalgic. It wouldn’t lead to headline slots at Coachella, of course, but as Radiohead and even Noel Gallagher said, the Britpop movement started as a celebration of the ’60s. So maybe it was always meant to be a wild romping nostalgia trip.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.

“I was writing songs from eight years old, but once I got a guitar I began to deeply identify with music… building an arsenal of influences”: How Lea Thomas uses guitars her dad built to conjure a magic synthesis of folk, pop and the ethereal

“I liked that they were the underdogs. It was not the mainstream guitar. It was something that was hard to find”: Vox guitars deserve a second look – just ask L.A. Witch’s Sade Sanchez, who’s teaming hers with ugly pedals for nouveau garage rock thrills

![OASIS - Some Might Say (Live at Knebworth) [Sunday 11th August, 1996] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/jj_jJl5bBfU/maxresdefault.jpg)