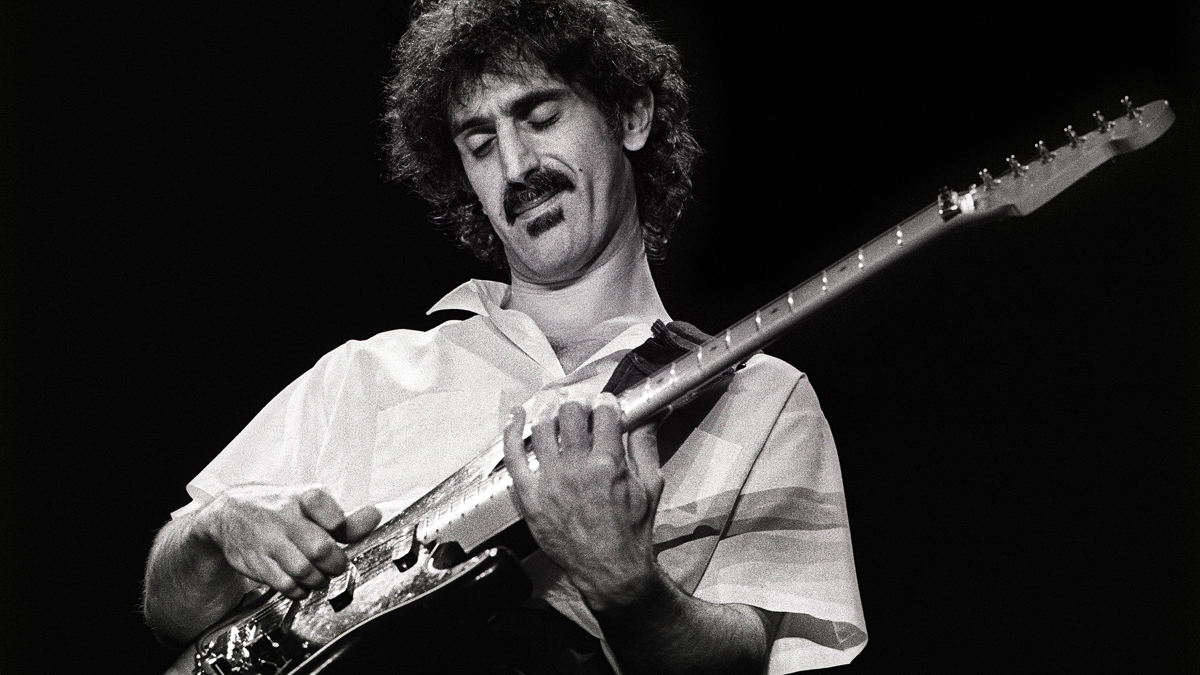

The life and times of Frank Zappa – composer, satirist and towering giant of the electric guitar

Looking back at the career of the one-of-a-kind musician and guitar visionary

The following is an excerpt from the February 1999 issue of Guitar World.

“There’s no single ideal listener out there who likes my orchestral music, my guitar albums and songs like Dyna-Moe-Hum,” Frank Zappa told me in 1988. “That’s why sometimes I’ll do an orchestral album, and the people who like guitar stuff can’t stand it. And then a guitar album comes out, and the people who liked the orchestral album can’t stand that. But you know, they’re all my friends in their own way. So why not accommodate them all?”

Now that Frank is gone, it’s somehow comforting to reread those words. Frank Vincent Zappa was notoriously intolerant of the imperfections in human nature. With a few curt remarks, he could decimate an audience member foolish enough to shout out a song request, or a journalist presumptuous enough to concoct a half-assed theory about him. Yet he was willing to consider all of us who love his music as “friends.”

There are rabid Zappa fanatics out there who would insist that it is possible for one person to admire Zappa’s knotty, inventive orchestral compositions, his honking, brilliant guitar work and the prickly combination of sociology, satire and schoolboy scatological that went into his song lyrics. But it’s no small undertaking.

Frank Zappa’s 60-album oeuvre is an imposing body of work. Some of the records are better than others, but the overall quality level is astonishingly high. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Zappa was still in top creative form at age 52, when he succumbed to prostate cancer – on December 4, 1993 – after battling the disease for several years.

We’ll never know what he would have achieved had he lived another 20 or 30 years. But we can console ourselves with the fact that, in the brief time allotted to him, he accomplished far more than most humans.

Beyond his having been a superb composer and musician, Frank Zappa was also a committed and capable political activist, an innovative filmmaker, able businessman and one of our century’s all-around bona fide smart guys. He raised rock’s IQ more than a few notches.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Frank's first steps

“Scientists believe that the universe is made of hydrogen, because they claim it’s the most plentiful ingredient. I claim that the most plentiful ingredient is stupidity.” That’s what Zappa said in an interview, just a few months before his death, with Pulse! magazine’s Dan Ouellette.

The “hydrogen” quote was one of Frank’s favorites; it cropped up a lot in interviews down through the years. And in many ways, Zappa’s whole life was a battle against stupidity – the stupidity of mass media conformity, the stupidity of a greedy, inept, ignoble government, the stupidity of thinking it’s cool to be stupid.

Frank liked facts, so here are a few now: He was born on December 21, 1940, in Baltimore, Maryland. (His childhood is hilariously chronicled in his 1989 autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa Book [Poseidon Press].)

When he was around 10 his family moved to the dismal suburban environs of Lancaster, California. There, he became interested in two strangely dissimilar forms of music: the black R&B and blues sounds of the day, and the early 20th century avant garde compositions of Edgard Varèse, Anton Webern and Igor Stravinsky.

Both influences can be heard throughout his music. But his blues inspiration is most strongly felt in his guitar work. In 1988, he told me about one of the key experiences of his youth:

“It was when I first heard the guitar solo in Three Hours Past Midnight, by Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson. That’s probably one of the most important musical statements I ever heard in my life. And also the guitar solos on I Got Something For You and The Story of My Blues, by Guitar Slim. And Lover Man by Wes Montgomery.”

Another blues artist influenced Zappa in a way that is often overlooked. In a 1980 interview for Trouser Press, Frank told Michael Bloom that he first grew his trademark goatee and mustache because he “thought it looked good on bluesman Johnny Otis.”

As a teenager, Zappa played drums and guitar in a variety of local R&B hands. By the time he reached his early 20s, he’d owned and operated his own recording studio (Studio Z), composed B-movie scores, tried his own hand at filmmaking and co-authored a doo-wop tune called Memories of El Monte, which was recorded by the Penguins.

Around 1964, Zappa took control of the R&B bar band he was then playing with – the Soul Giants – persuading them to try some songs he’d written. He also changed the name of the band to the Mothers, an event of incalculable sociological importance.

The Mothers came into their own on the mid '60s Los Angeles freak scene. It is generally accepted that hippiedom began in San Francisco. “But the scene in Los Angeles was far more bizarre,” Frank wrote in his autobiography. It was the L.A. underground that gave birth to the Doors, the Byrds, the Seeds and several other fine bands whose names have not become part of Official Rock History. Needless to say, the Mothers were far weirder than any of these acts.

In an era when even the “dangerous” rock bands were still pretty clean and cute, the Mothers were unkempt and ugly, and some of them would very obviously never see 25 again. The wild melange of sounds they generated included some decidedly unfashionable musical styles like doo-wop and lounge jazz. But at this particular juncture in cultural history, the weirder something was, the better it was generally esteemed to be.

This was one of those times when record companies couldn’t figure out what the hell was going on with “those crazy kids” and their music, so they were signing all kinds of interesting acts with “no commercial potential.” This included the Mothers, who were offered a contract with MGM’s Verve label.

Freaking out the world

1966 saw the release of Freak Out!, the debut album by the Mothers of Invention. (The record company suggested adding “of Invention” to the band’s name, since the word “Mothers” by itself sounded too close to the popular shortened form of “motherfucker,” which – for reasons too complex to detail here – was a very potent word in the hippie counterculture of the mid to late '60s.)

By any reckoning, Freak Out! is one of the most influential rock albums of all time. It is generally considered the first “concept album” and also the first double album in rock. It contains the seeds of all Zappa’s later work.

The first two sides are devoted to songs – satirical, humorous, angry, topical, carefully and resourcefully arranged songs, played with exacting precision. On the second disc, the presentation grows increasingly free-form, culminating in The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet.

This piece takes up all of side four (pretty revolutionary in ’66) and offers an aural glimpse of “what freaks sound like when you turn them loose in a recording studio at one o’clock in the morning on $500 worth of rented percussion equipment,” to quote Zappa’s liner notes.

Freak Out! almost instantly acquired a reputation as the Number One Album to Take Drugs To, much to the chagrin of its composer, who was resolutely straight all his life

Freak Out! and the Mothers’ subsequent Verve albums did much to establish the Zappa mythology. Frank’s log cabin home at 2401 Laurel Canyon Blvd., in an L.A. neighborhood heavily populated by rock stars, assumed Olympian proportions in the minds of his fans.

John Mayall even wrote a song about his stay there. Frank’s friends and associates – who bore names like Suzy Creamcheese, Dakota and Motorhead – acquired the larger-than-life stature of Zeus, Hera, Pan and Aphrodite to a generation of suburban teenage misfits.

These youths felt tremendously empowered by Freak Out!, and its implication that not only was it okay to be a bit strange, frizzy-haired, unpopular and a little too intelligent, it was positively cool.

But not everything about the Zappa myth was pleasing to the man at its center. Freak Out! almost instantly acquired a reputation as the Number One Album to Take Drugs To, much to the chagrin of its composer, who was resolutely straight all his life.

By 1967, Zappa and the Mothers had migrated to New York, where they began their now-legendary six-month residence at the Garrick Theatre in Greenwich Village. The Mothers basically moved into this decaying old 300-seater, doing two shows a night. Nobody could be certain in advance what was going to occur on any given evening.

Jimi Hendrix was one of the notable musicians who came down to jam. But in many ways, it was the audience who often provided the real entertainment. Here, during the height of the Vietnam War, Zappa one night convinced three drunken Marines to attack a baby doll with a bayonet on stage.

According to eyewitnesses, the ensuing spectacle made a more powerful anti-war statement than any protest song or political speech ever could.

These “audience participation” segments were to become a popular element of Zappa concerts throughout his career. There’s something completely emblematic of his work in the contrast between the perfectionist discipline of his music and his willingness to entrust a portion of his concerts to some inebriated schmoes randomly selected from the crowd.

It’s as though he wanted, not to impose order on chaos, but to incorporate chaos into the ordered perfection of his art. If the universe was gonna insist on being inherently stupid, Zappa was determined to find some positive, creative use for all that stupidity.

His entrepreneurial energies were boundless. 1967 also saw the release of his first solo album, Lumpy Gravy. The following year, after his relationship with Verve ended, he started two record labels of his own: Bizarre and Straight, both distributed by Warner/Reprise. Straight was Zappa’s label for presenting new talents he had discovered.

It was Frank Zappa who brought the world the first recordings by Captain Beefheart and Alice Cooper, as well as less-well-remembered artists like folksinger Tim Buckley, the aptly named Wild Man Fischer and the GTOs. The last was a vocal ensemble comprised of Hollywood scenemakers – including kiss-and-tell rock diarist Pamela Des Barres – who apparently had enough “pull” to entice talents like Jeff Beck and Rod Stewart to perform on their disc.

Bizarre was the label for the Mothers’ own records. The first to appear on the new imprint was 1968’s Uncle Meat. This double-album set is another landmark Zappa work, exhibiting a compositional flair and a gift for woodwind arrangement that far exceeded anything that had come before.

The liner notes describe this record as “an album of music from a movie you will probably never get to see.” Which was almost true. It took the invention of the VCR and the formation of Zappa’s own Honker Video company in the '80s for the world to see this bizarre cinematic document of the Mothers’ first incarnation.

My guitar wants to kill your mamma: Zappa in the '70s

Zappa had never abandoned the interest in moviemaking that he developed back in his pre-Mothers Studio Z days. But it wasn’t until 1971 that he was able to get a film into commercial release. This was 200 Motels, a surrealistic inquest into the proposition that “touring can make you crazy.”

200 Motels deserves a place in film history because of the video editing and effects techniques that Zappa pioneered in making it. Also, it has become a perennial favorite among zonked-out midnight movie patrons everywhere.

The accompanying soundtrack album is an essential Zappa work for several reasons. For one, it fully exploited the considerable capabilities of the new Mothers of Invention lineup that Zappa had debuted on the previous year’s album, Chunga’s Revenge. Zappa disbanded the original Mothers in 1969, largely for economic reasons. (By this point, by the way, he was firmly ensconced back in Los Angeles.)

The newly formed Mothers were fronted by humorists/vocalists Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman, formerly of the mid '60s teen pop group, the Turtles. The lineup also included jazz piano ace George Duke and British drummer Aynsley Dunbar, fresh from a stint with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. True to form, Zappa had surrounded himself with a fantastically diverse assortment of musical personalities.

200 Motels was also the first recording on which Zappa fans got the opportunity to hear his music played by a real symphony orchestra, Britain’s Royal Philharmonic, under the baton of Elgar Howarth. In stark Zappa-esque contrast, 200 Motels was also one of the first albums where Frank played really heavy guitar. Even today, tracks like “Magic Fingers” and “Mystery Roach” stand up as sterling examples of mastodon unison riffology and extended fretboard exploration.

Zappa regarded his guitar solos as a form of “instant composition. It’s basically the same intellectual process that I would go through writing music on a piece of paper, except that I don’t have to write it down; it gets done right away. But it’s really no different. You have a certain amount of time that you’re going to fill up by making a piece of music. And you hope that the people who are working with you on stage are also interested in inventing music on the spot. When it works, which is not very often, I’m glad I have a recording truck. I can snag it. Because it’s gone after that. That’s the only time it exists.”

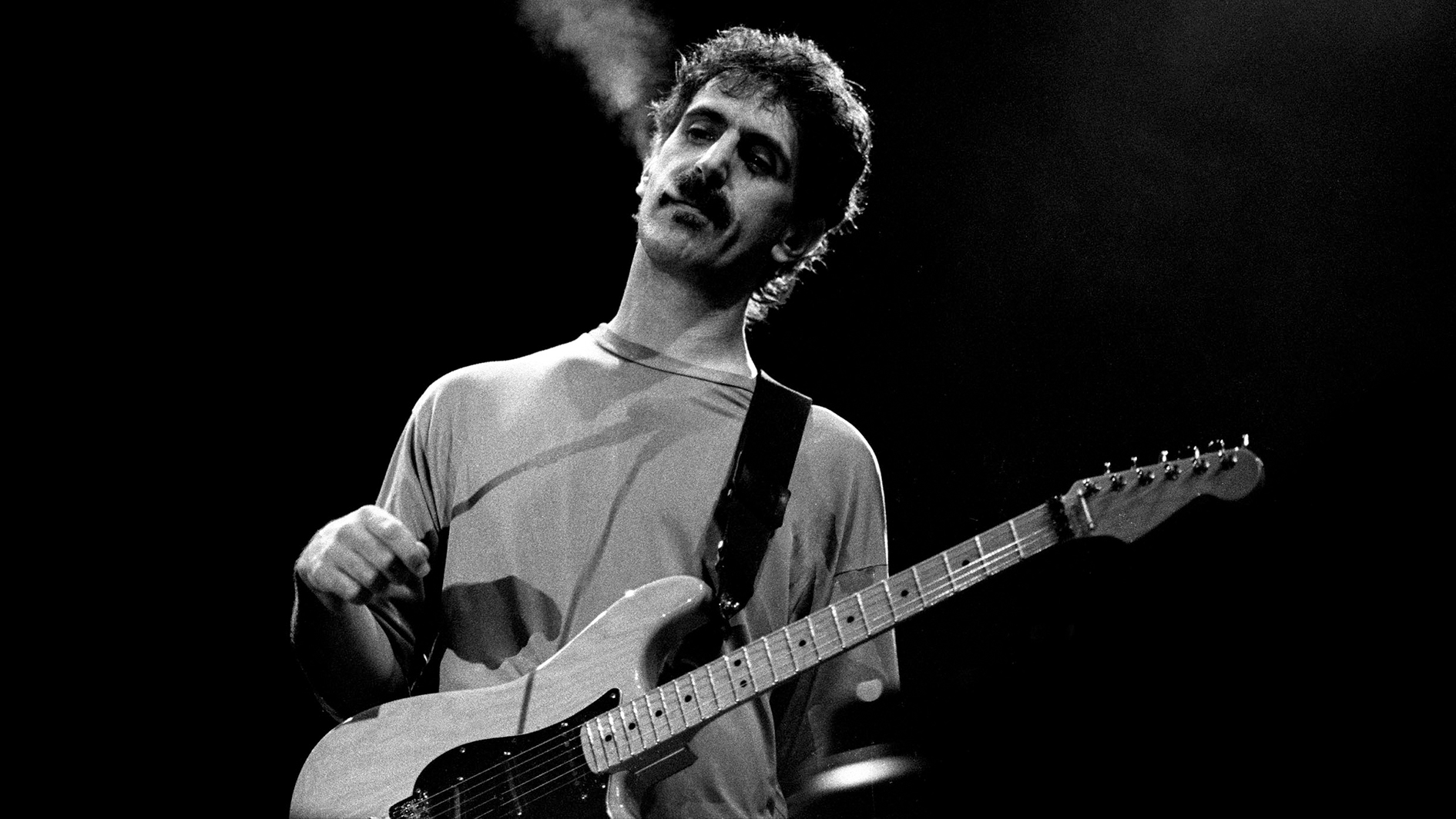

Zappa was incontestably one of the most interesting guitar soloists of all time. His blues grounding gave him an insistent earthiness, while his sense of avant garde, dadaist absurdity pushed him in directions that confounded all expectation. But more than anything else, it was his tone that made him a fiercely distinctive player. His guitar sounded like a gander with a bad sinus condition. He made brilliant use of a wah wah pedal, and was one of the few guitarists of the '70s and '80s to exploit the lower strings and fret positions to their full potential. He laughed when I complimented him on this.

“Well, I think most guitarists have a tendency to play in some way like they talk,” he said. “And since I’m not much of a squealer – I happen to be a baritone kind of guy – to play on the low strings is a little more in phase with my reality.”

Zappa really came into his own as a gonzo guitarist in the '70s. The decade’s inaugural year saw the release of his exquisite, heavily guitar-driven solo album, Hot Rats. The same year also brought the Mothers’ aforementioned Chunga’s Revenge and Weasels Ripped My Flesh. Both feature some flaming beauties of guitar solos. The latter album includes the original recording of Zappa’s axe anthem, My Guitar Wants to Kill Your Mamma.

The lineup in Zappa’s bands changed regularly throughout the '70s and early '80s. His groups became increasingly polished from a technical standpoint as he found himself more and more able to draw on top session talent and noted players from every field of music.

Zappa was a formidable, notoriously demanding band-leader. His band was generally recognized as a hothouse for extremely proficient players; it’s alumni include the guitarists Lowell George, Adrian Belew and Steve Vai.

Some fans of the original Mothers felt that Zappa’s work had become a little slick at this point. The truth is, however, that he’d always used session players. Examine the liner notes to Freak Out! and you’ll find studio aces like Carol Kaye – and even Lawrence Welk’s guitarist, Neil Le Vang – clearly credited.

Frank never paid much attention to his musicians’ underground credibility. Original Mothers fans also tended to find Kaylan and Volman’s brand of humor a little too broad, obvious and infantile. A new legion of fans, however, liked it just fine.

What did happen during the '70s is that Zappa’s albums began growing more “unidirectional.” He began sorting out the different strands in his work. His early albums combined satire, serious composition, gross-out jokes and jazzy improvisation, all in one gloriously multifaceted package. Later on, he would focus on just one of these elements for any given album.

A record like 1973’s Overnite Sensation is heavy on humor, whereas The Grand Wazoo (1972) is mostly about composition and jazz-based soloing.

The highly specialized '80s

In the '80s, Zappa took this trend toward specialization to a new level with the release of the Shut Up ‘N Play Yer Guitar series, an orgy of guitar solos and nothing else, directed straight at the coterie of Zappa axe junkies.

By this point, he had started a new label, Barking Pumpkin, and his own marketing/mail order operation, Barfko-Swill, after his deal with Warner/Reprise and a subsequent arrangement with Mercury Records had gone sour. Zappa maintained close ties with his fans. Unlike many rock stars he was highly accessible.

“When we’re on the road there are kids who follow us from town to town,” he explained in 1988. “If we see the same faces when we arrive at the venue for an afternoon soundcheck, we let them in and they sit through the soundcheck. And you know, I talk to these people. They tell me interesting things. For example, a fan in Germany was the first to point out that there were incorrect dates and locations in the liner notes for You Can’t Do That on Stage Anymore.”

Frank deemed this kind of networking essential in the face of what he regarded as an increasingly incompetent, crooked and imbecilic music industry. Marketing his own music was “the only way I can exist,” he told me. “There’s no way that what I do can fit within a corporate format. In the United States, radio is a cultural embarrassment. Most of the music that’s broadcast is harmful to your mental health.”

The early '80s brought many opportunities for Frank’s orchestral and chamber compositions to be recorded and performed. 1983 saw the release of the first London Symphony Orchestra disc, which was followed a year later by The Perfect Stranger: Boulez Conducts Zappa.

During this period, there were also performances of Zappa’s music by ensembles such as the Kronos String Quartet and Aspen Wind Quintet. These developments were very gratifying to the composer, who had long sought an outlet for his more serious work.

But he entertained no illusions about the classical music power structure. He found it every bit as frustrating and foolish as the pop music industry. Zappa was no snob.

“I have no following or any pretensions to a following in the normal classical consumer environment,” he told me in a 1984 interview. “The normal audience for an orchestral piece wouldn’t be caught anywhere in the vicinity of what I write. It’s just not relevant to their lifestyle, nor is it written for their tastes. Basically, the material is written to amuse me and anybody else who has a similar musical outlook.”

Zappa may have found his ideal musical collaborator in the Synclavier computer music system (a high-end music workstation), which also entered his life in the mid Eighties. “What I’ve been waiting for since I started writing music was a chance to hear what I write played without mistakes and without a bad attitude,” he said in 1984.

“The Synclavier solves that problem for me.” The Synclavier-based Jazz From Hell album won Zappa a Grammy in 1988. He was somewhat obsessed with the device. When I spoke to him in 1988 he estimated that he had some 500 new compositions stored on computer disc: “I work every night on that. My Synclavier hours are usually from about 11:00 at night until 7:00 in the morning.” Nocturnal in his work habits, Zappa preferred to be asleep while the rest of the world went about its dubious business.

Frank embraced the digital revolution wholeheartedly. As soon as the Compact Disc format established itself, he threw himself into the monumental task of remastering his entire back catalog for CD release through Rykodisk.

Later, he embarked on the equally ambitious Beat the Boots series for Rhino Records, offering quality masterings of his live concerts as an alternative to the unauthorized bootleg Zappa product that has been flooding the market ever since the Sixties.

The pristine digital perfection of the Synclavier took Zappa entirely away from guitar playing from 1984-’88; he said he didn’t touch the instrument once during that period. But in 1988, he assembled a band, its members culled from the cream of the players he’d worked with during the '80s – including guitarists Ike Willis and “stunt” axeman Mike Keneally – for a world tour. The results, which are among Zappa’s last public performances on guitar, can be heard on two discs: Broadway the Hard Way and The Greatest Band You Never Heard in Your Life.

Amid all these projects, Zappa also found time to become a vigorous political activist. In 1985, he testified at the U.S. Senate’s “porn rock” hearings. He became one of the most outspoken and eloquent campaigners against the censorship of rock music, a tireless free speech activist and protector of constitutional rights.

In 1989, after the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, Zappa was invited to Czechoslovakia by the country’s new president, Vaclav Havel, as an economic advisor. For several months, he acted as the country’s economic representative to the West. Zappa was increasingly drawn to politics. It’s reported that he was planning a serious presidential campaign.

This was one of many plans that were canceled when he was diagnosed as having prostate cancer in 1990. According to an article in Pulse!, the condition had been developing for some eight to 10 years before it was detected.

Rumors of Frank’s illness began to spread in the music industry shortly after the diagnosis. At first, they were widely disbelieved; it just seemed like another stupid, obviously untrue Frank Zappa story. But when the family confirmed the rumors, there was no more denying the grim fact.

Zappa continued working right up until the end. As a result he was able to see the release of one last recording of his music, The Yellow Shark, performed by Frankfurt’s Ensemble Modern. This lavish and beautifully realized album reaches all the way back to compositions from Uncle Meat – a fitting end to a wondrously rich career.

But we’ve hardly heard the last of Zappa’s music. Frank’s unflagging creative energy left behind a legacy of unreleased compositions and recordings that will sustain us for many years to come. Not long after his death, Rykodisk released the superb Zappa orchestral work Civilization Phaze III. There has been a steady stream of Zappa reissues and compilations of previously unreleased material, including The Lost Episodes, Lather, Have I Offended Someone and Mystery Disc. Zappa’s unflagging creative energy left behind a musical legacy that will sustain us for many years to come.

“I am a realistic kind of guy,” Frank told Guitar World’s John Swenson in 1982. “I just try and look at things the way they are, take them for what they are, deal with them, and go on to the next case. But Americans thrive on hype and bloated images and bloated everything. They turn away from anything that’s realistic. They want the candy gloss version of whatever it is.”

And that’s the one version that Frank never played.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

“This would make for the perfect first guitar for any style of player whether they’re trying to imitate John Mayer or John Petrucci”: Mooer MSC10 Pro review