“If you can make a record that feels like you have invented rock ’n’ roll, that’s a great feeling”: The Hives on how a need for speed – and the mystery of the elusive Randy Fitzsimmons – helped inspire them to make a comeback record for the ages

Nicholaus Arson and Vigilante Carlstroem discuss The Death of Randy Fitzsimmons, and the elemental, perfect fusion of high-volume guitars, a beat, and a vocal

Rock ’n’ roll is an art form of myth and illusion. Of the latter you have that strange quirk of physics and biology whereby the more you turn up the volume, the faster it can feel. Of the former, well, pick your own favourite.

The Hives, the biggest garage rock band in the world, and principally responsible for the revival of the garage sound at the turn of the 21st century, traffic in both. But it’s myth that sets the scene for their long-awaited studio album, The Death Of Randy Fitzsimmons.

The identity of Randy Fitzsimmons has been the subject of conjecture since the start, his legend the shadow under which The Hives sound takes form. The story goes, he writes the songs, the band get to work and breathe life into the arrangements. Only Fitzsimmons was meant to be dead, hence The Hives’ studio hiatus.

Besides the occasional single and festival appearance, the band had laid low. Some outlets have named lead guitarist Niklas Almqvist, aka Nicholaus Arson, as the real Fitzsimmons, but can anyone be so sure?

He certainly doesn’t volunteer that information when he joins us over Zoom, with rhythm guitarist Mikael Karlsson, aka Vigilante Carlstroem, patched in from his vacation after a hectic summer shaking stadiums in the company of the Arctic Monkeys and filling in dates with club shows. That they answer to aliases only deepens the mystery.

This album, their first since 2012’s Lex Hives, was constructed around the myth of Fitzsimmons’ apparent death, and the story The Hives are sticking to is that they read his obituary in a local paper, visited his grave, dug it up, and instead of a pile of bones they found a set of songs, an album waiting to be made, and the stage wear to perform them in.

If their story checks out, you could call The Death Of Randy Fitzsimmons the world’s first found footage rock ’n’ roll album – Bo Diddley meets The Blair Witch Project. But really, once you press play on Bogus Operandi, the lead single that opens the record, it is business as usual. Down low, it sounds in the red, studio limiters creaking, electric guitar, drums, and bass pushing everything. Crank it up and it sounds faster…

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

We recorded through tape, and the tape was pushed quite a bit so it gets a lot of volume, going into the red on the tape

Vigilante Carlstroem

“We recorded through tape, and the tape was pushed quite a bit so it gets a lot of volume, going into the red on the tape,” says Carlstroem. “It makes the guitar sound kick-ass.” One of the performance-related benefits of tape comes from its limitations: the fact that it is perishable, finite, and it isn’t as cheap as it used to be. Whenever you roll it you better make it count. Carlstroem says they “pretty much always” track to tape at some point in the recording.

“I think it is way better on tape. Not everything is recorded on tape but at least us playing live in the studio is,” he says. “When you record you are always more excited on the first take, and then maybe the same excitement on the second, but then it goes down.

“When you do it 10 times in a row you start missing something. That’s the way it goes. Rehearse the song until it sounds good and then try and smash it down in one take. That’s when I think we get the most exciting sound, and when we play it over and over again it gets more flat. I like the feeling of the first take.”

'Feeling' is the word that keeps coming up. Rock ’n’ roll is about myth and illusion but it is also about feel. It is about instinct. It is above all about being human. That rock ’n’ roll works best when there’s danger in the air is fundamentally human; it’s us reckoning with our mortality.

The only way to cheat death is to create a legend. Everything might be logged forever in the digital architecture that holds our lives together but achieving immortality is still something that requires storytelling and a sense of theatre, something that’s a dying art in the information age.

Whether theirs works for you or not, The Hives are nonetheless pursuing such legends. “If you can make a record that feels like you have invented rock ’n’ roll or you have found the first rock ’n’ roll album, that’s a great feeling,” says Arson.

To make this sort of sound you have to forget best practice and abandon the sort of precautions that are routinely applied in studio recording. On tracks such as Crash Into The Weekend, The Hives sound like they’re all competing to be ahead of the beat. Keeping everything aligned on the grid is too antiseptic, too “safety first” for their sound. “That just makes it sound artificial, and uninteresting for the most part,” says Arson. “For me, anyway.”

“I am way behind, the bass player is a little in front,” says Carlstroem. “That’s the key to the song, I think. I’m lagging, Nicke [Arson] is speeding up, and the bass player is on the beat.”

“Yeah, that’s probably true in 90 percent of the time,” adds Arson. “But every once in a while you get someone going in with a good feeling of something and just rush and then you’ve got to tag along.”

And yet it all functions as intended. Our ears make sense of it. The hooks are hard to quit. Riffs are easily digested. Another illusion The Hives specialize in is simplicity. Arson says their arrangements are anything but. All rock is math rock; you need to count. He says The Hives try to mix up the counts without the audience noticing. Why divide everything up into four? “That’s something that we take a little bit of pride in, to find that arrangement that might be odd to some but sounds the most natural,” he says.

“Some of The Hives' songs are really complicated arrangements,” adds Carlstroem. “But that’s the trick, I think. It should sound simple.”

There are lots of textures and sounds deepening the mix. Take a track like The Way The Story Goes, which has this Twilight Zone bizarro atmosphere, an after hours feel in a mix that’s punctuated by hand claps, surf guitar with a generous lick of spring reverb, or Two Kinds Of Trouble, which comes from the Mutt Lange school of arrangements wherein big open spaces give drums some space to boom.

Smoke And Mirrors has a Ramones quality in that it has a ballad’s sentiment but is performed around 150bpm. “That started out as some sort of rockabilly pop song,” says Arson. “The inspiration was [the classic Ramones album] End Of The Century. We love the early stuff as well but the late Ramones stuff is very underrated.”

Long-time Hives collaborator Pelle Gunnerfeldt engineered and mixed the record. Producer Patrik Berger can take some of the credit for how far The Hives stretched their sound without calling attention to it. Berger has worked with the likes of Charli XCX and Lana Del Rey, and brings that box-office quality to the production. His punk background is just as important.

“You want someone to challenge you on the arrangements, on the songs,” says Arson. “He comes from a slightly different school from us. He was in punk bands as well, bands sort of based on the first GG Allin records, but he was also in psychedelic bands. He has made pop hits as well. He has been all over the place, and we wanted someone with an eclectic taste in music to come in and challenge us.”

It was Berger who suggested that they should use their live rigs in the studio, Fender amps pushing air through the grille cloth, Arson on his 1975 Telecaster Custom. Carlstroem invariably used a Fender Vibro-King, with a few effects in front when the song called for it. Two Kinds Of Trouble did, and deploys a gnarly gated fuzz.

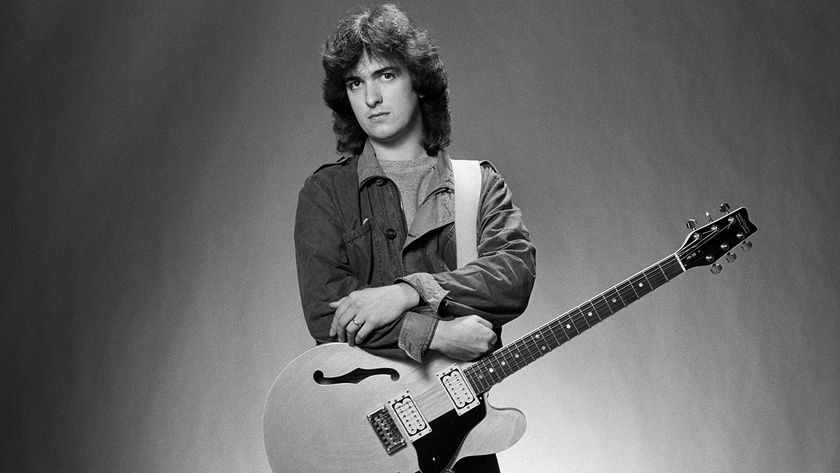

“I know what that is,” he says. “That is a Fuzz Factory, and it’s a Vibro-King, and a [Mad Professor] Deep Blue Delay.” And the 1959 Epiphone Coronet that he has has been his number one for over 20 years. You might have seen Carlstroem playing an Ivison Hurricane at Glastonbury. Ivison Guitars fixed up the Coronet after a headstock break. If and when Carlstroem finally kills it, it’ll die hard. “I’ve been trying, hard, but it’s still alive,” he laughs.

So, too, is Randy Fitzsimmons, whoever, wherever he may be. The Keyser Söze of garage rock might elude us yet. Arson is happier theorizing about the greatest trick that rock ’n’ roll ever pulled – the one that volume plays on the body and mind. Without that, you’ve got nothing.

“If rock ’n’ roll gets your heart pumping then that would be the sum of it, it feels faster,” he says. “When you turn up the volume, it is supposed to sound wilder. That’s always been important to us.”

- The Death Of Randy Fitzsimmons is out now via Disques Hives.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

“An investment-grade, pro-quality guitar that will provide decades of playing enjoyment before it becomes a treasured family heirloom”: Taylor Gold Label 814e SB review

“Satin Stratocaster dreams”: Fender and Thomann have produced two new exclusive Stratocaster lines – and their prices rival existing US and Mexico-made models