The history and mythology behind Fender's rare Blackguard Telecasters

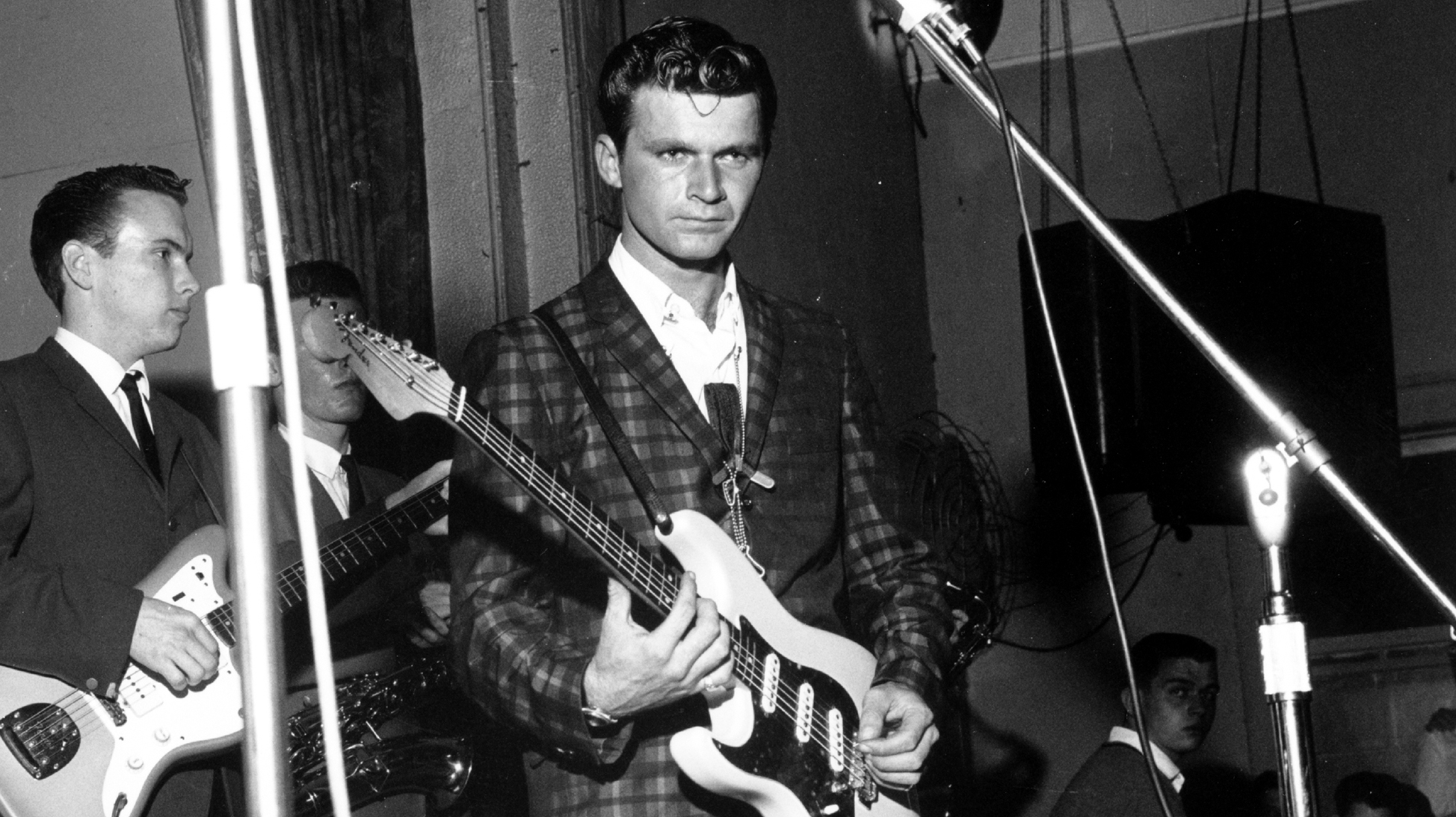

Historic Hardware: Tele expert Richard diZerega walks us through the Blackguard era of Esquires, Broadcasters, Nocasters and Telecasters

I was always a Strat guy, but as I got more into vintage Fenders, I thought, ‘Blackguards are really where the history’s at,’” begins Richard diZerega.

As a player, collector and avid researcher of vintage guitars, Richard’s deep fascination with Fender’s fledgling solidbody designs led to the creation of BlackguardLogs.com – a website dedicated to preserving Fender history by filling the gaps in factory records while identifying and detailing individual instruments.

“What really drew me to Blackguards was the history,” he continues, “and once I got it, I was like, ‘What have I been missing out on?!’ “There are so many myths surrounding Blackguards, including the hype that’s around the name Tadeo Gomez. A Tadeo-signed neck is considered by many to be the Holy Grail of Fender necks. Truth is, there’s no evidence to back up that narrative.

“He was an unskilled labourer responsible for finish sanding. For us to hold him in higher regard does a disservice to Leo [Fender]. Leo almost bankrupted himself by investing in new tooling so that they could hire someone who needed minimal training to help build a guitar.

“They wanted people to be productive within hours, not weeks. It’s like the Henry Ford approach: they didn’t want an engineer to step in at every point in production.

“The community sometimes gets very defensive at this perspective, saying I’m attacking Tadeo. I personally think the hype is self-serving to Tadeo neck owners, but I own two Tadeo signed necks and I’ll be the first to say it’s hype.”

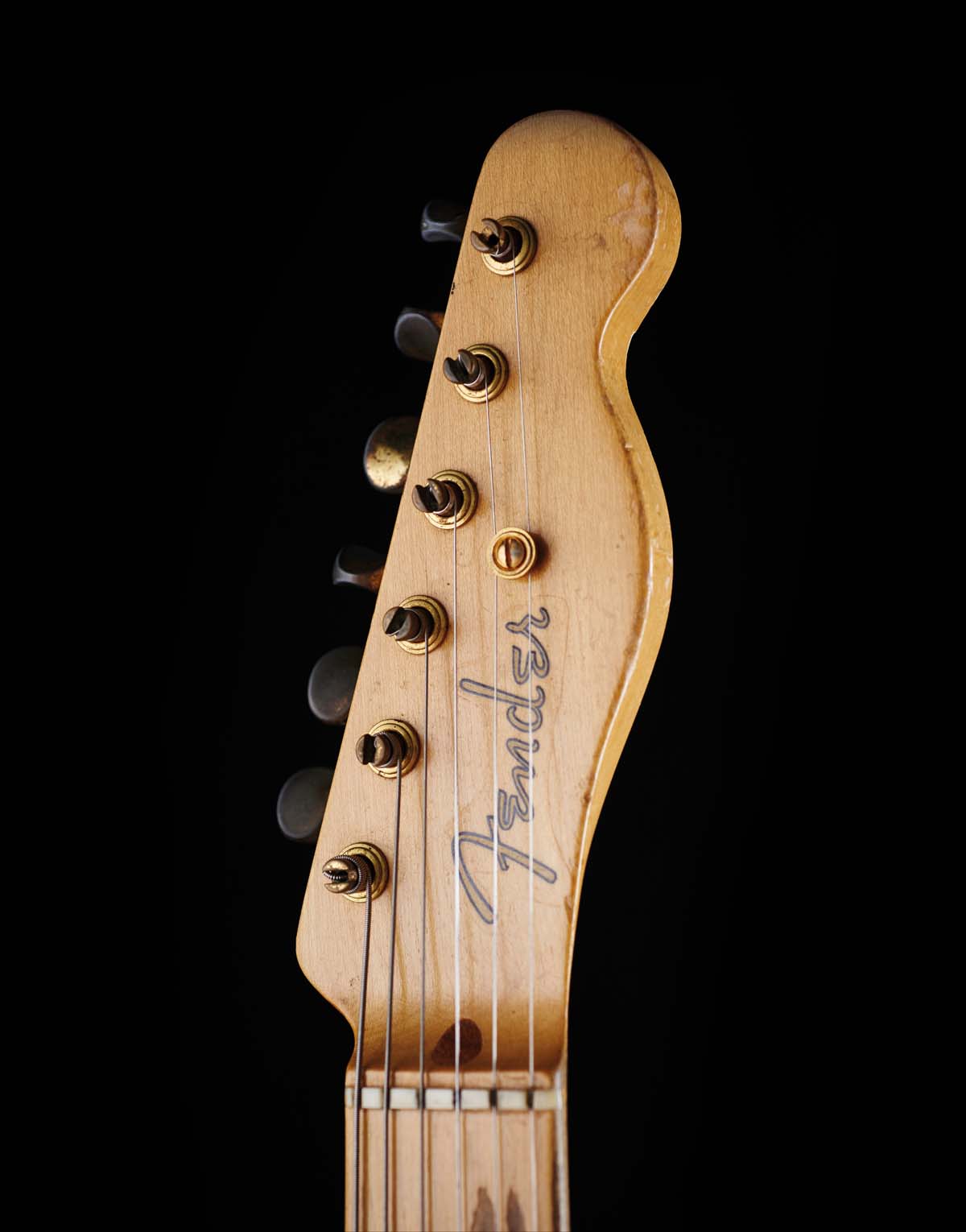

The biggest myth bar none is that you can tell what year a Blackguard is based on the serial number

Although more and more pictorial and factual evidence is surfacing thanks to the concerted efforts of Fender historians worldwide, countless myths have arisen over the years in the absence of factory records – notably shipping figures and serial number information.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The biggest myth bar none is that you can tell what year a Blackguard is based on the serial number,” reveals Richard. “They are all over the place. For example, BlackguardLogs.com has recently been posting guitars around the 2200-3000 range. Those are generally ’52 Telecasters, but Mike Campbell’s famous 1950 Broadcaster has a 29XX serial number.

“One of my favourite guitars is a guitar formerly owned by the great Redd Volkaert. It’s [serial number] 0065, which is a really low number, but it’s a [1951] Nocaster, not a Broadcaster. The biggest falsehood by far is that you can date a Blackguard based on its serial number.”

All Blackguards feature a bridge pickup with flat polepieces. Brass saddles were replaced by steel saddles in late 1954 when the serial number relocated to the neckplate and white pickguards became standard.

With the selector switch in the back position, what we now consider to be a ‘tone’ knob functioned as a blend control between both pickups on Broadcasters, Nocasters and early Telecasters.

A close-up of this 1950 Broadcaster shows the typical flaky finish with both vertical and horizontal checking.

1950 Broadcaster with original ‘thermometer’ case, strap and bridge cover. These snap-on covers are often referred to as ‘ash tray’ covers on account of their alternative (and perhaps more practical!) use.

In addition to a lack of factory records, the ability to identify original Blackguards is hampered by the numerous fakes and guitars with non-original parts.

“I love statistics,” enthuses Richard. “It’s always interesting to go and look at the min and max serial number by year, or min and max serial number by model. But the problem is these guitars are several decades old and it’s so easy to take a bridge off of one guitar and put it on another. [Serial numbers relocated from the bridge to the neck plate in late 1954.] There’s no telling what history has been harmed in that respect.

“There’s also a pretty big problem with fakes these days. It’s like that old joke: ‘Gibson built about 1,700 ’Bursts, but only 2,000 have been found.’ It’s similar for Blackguards, especially Broadcasters.

“BlackguardLogs.com already has 177 Broadcasters registered and we don’t know exactly how many Broadcasters were made, but some people will say the figure is as low as 200. Now, there’s no way we’ve captured that high a proportion! Some of them get converted to make it a more valuable thing – perhaps with a new decal or maybe with something more malicious.

“I see white-’guard guitars [Telecasters and Esquires from late ’54 onwards] converted to Blackguards all the time. I’ve caught several dealers out when I’ve had pictures of guitars – including their serial numbers – with white ’guards, that they’ve later advertised as Blackguards. It is a struggle.

“Any time there’s value in something, there will be people trying to cheat others. Blackguards have increased in value so much and it’s a hot market right now. More so than Strats, easily. Somebody recently posted a ‘near mint’ ’53 online asking what people thought he could get for it and he’s now trying to sell it for $65,000. I think he’s high, but he’s not that high. I think he could easily get $55,000 for it.”

There’s also a pretty big problem with fakes these days. It’s like that old joke: ‘Gibson built about 1,700 ’Bursts, but only 2,000 have been found.’ It’s similar for Blackguards

Although it’s not advisable to date Blackguards using serial numbers, an expert with a well-trained eye can provide an accurate assessment of originality and condition based on a range of details including body/routing, finish, neck profile, hardware, plastics, pickups, electronics, pot dates, and markings.

“A lot of the time, you can take a look at the finish and get an idea of what year the guitar is from,” Richard tells us. “They were constantly fine-tuning the finish. If you look at pics of Broadcasters that have an original finish, they’ll often appear very flaky and can have checking in both vertical and horizontal directions. I would say that was a defect of the Broadcaster into early ’51.

“My [May 1951 Nocaster] is a much lighter finish than [on] later [models]. In ’52 to ’53 the finish starts becoming thicker; it’s very easy to see that. I think the typical yellowing has more to do with environmental factors than UV discolouration, such as sweat and tobacco. In the ‘50s, smoking was super common – virtually everyone smoked – and I think that especially contributed to the darkening of Blackguard finishes.”

The Blackguard’s iconic blonde finish, often referred to as ‘butterscotch’ on account of its aged yellow hue, is transparent and so reveals each guitar’s unique ash body grain ‘fingerprint’. Although Leo’s choice of wood may have ultimately been a matter of cost, the decision to use ash was also based on aesthetics.

“The earliest Blackguards had pine bodies, but I think wood was more easily available back then and pine was quickly replaced with ash, probably because of the grain,” reasons Richard. “Those old swamp ash bodies have a great-looking grain. Occasionally, you’ll see a quarter-sawn body where the grain looks completely different – it’ll be tighter because of how the board was sawn.

There is something magical about Broadcasters, but most tend to be really heavy.

“One-piece bodies were present throughout the Blackguard run, but I feel like I see more in the early years. Two-piece bodies are more common and can even have a diagonal seam. This is sometimes accentuated by the grain not being matched very well. It looks much more obvious when it’s going in one direction and then it suddenly goes in another.

“There is something magical about Broadcasters, but most tend to be really heavy. It’s not unheard of to find a Broadcaster weighing nine pounds – you’re getting into Les Paul weight there! There’s a lot of variation.

“At this point, Fender were fine-tuning things, certainly through ’50 to ’51, and in ’51 they started to hit their stride. ’52 is a good period and a lot of people feel that ’53 is the year when things really came together.

“The ’53 Tele was a workhorse of Roy Buchanan, James Burton and Danny Gatton. ’53 is a sweet spot year. In my mind, that’s when things got really consistent. I don’t see as many ’54 Blackguards, probably because Fender were investing so much in the Stratocaster in early ’54, and switching [Teles] over to white ’guards.”

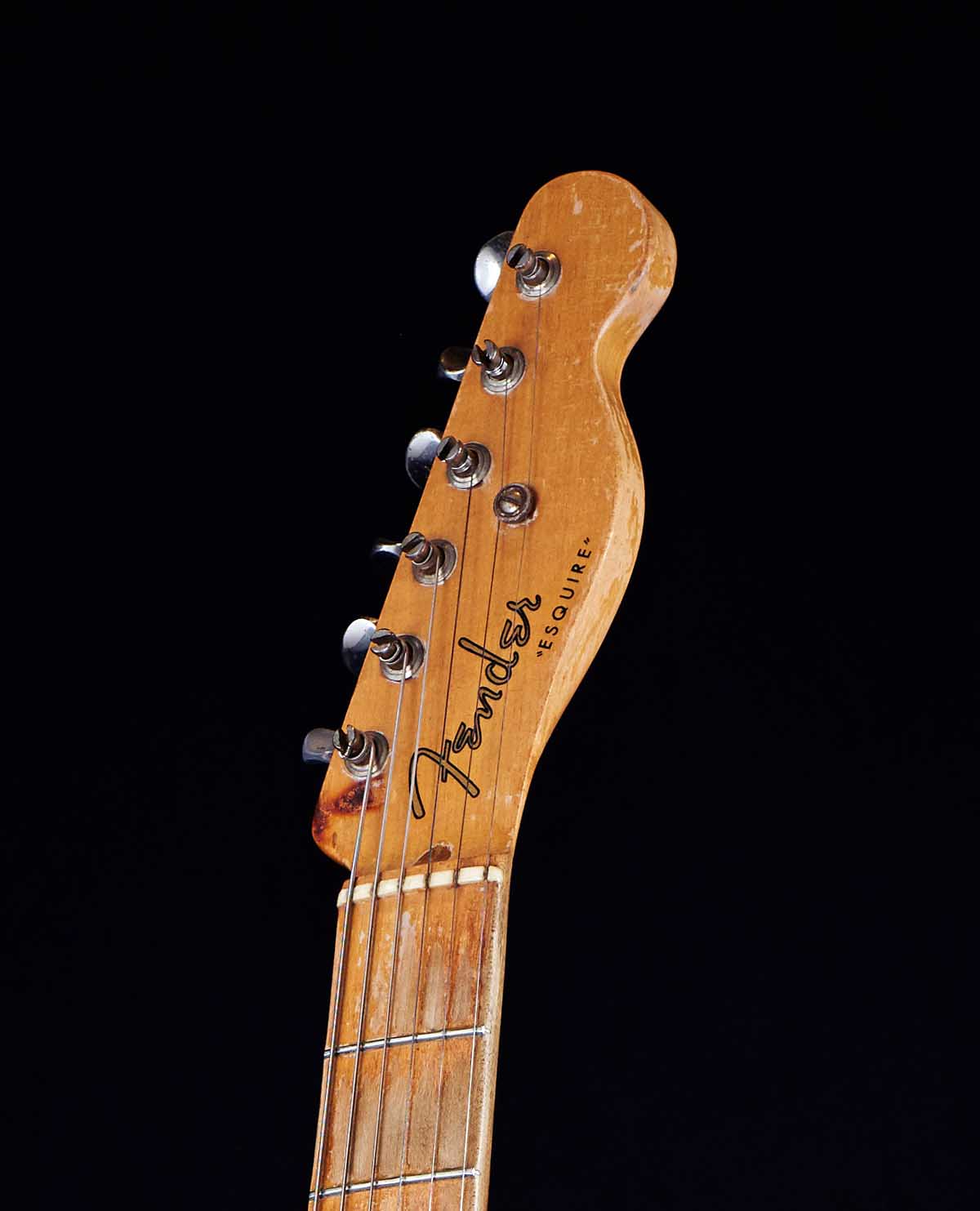

By autumn 1950, dual-pickup models were labelled as Broadcasters while the Esquire designation was retained for their single-pickup counterparts.

Featuring one or, rarely, two pickups, the earliest Fender solidbodies appeared under the Esquire moniker in the spring of 1950.

Changing shape over time, the early Blackguard necks are renowned for their profiles, as Richard explains.

“Although profiles vary, I generally see bigger, thicker necks in the early Blackguard years. They probably got feedback from musicians that they were a little fatiguing to play for a long time. It’s possible they made it thicker to begin with to give it some extra strength as Leo didn’t want to put a truss rod in initially.

“I wouldn’t call them baseball bat necks, but most early Blackguards have a very full profile. My ’51 Nocaster has that kind of profile. When I first got it, it was fatiguing to play for a long period of time because I wasn’t used to it – I was more used to playing Strats from ’56 or ’57 that were a soft ‘V’ profile. Profiles seemed to slim down in ’52 and increase again in ’53 through ’54, but they are hard to generalise.”

Blackguards are also notable for their unique pickups and control configurations.

“The Tele bridge pickup changed from flat to staggered polepieces in late ’55, and I’d put the flat pole Blackguard bridge pickup up against a PAF any day,” challenges Richard. “It has such a wide variety of tone. To me, it feels like the best of playing a Gibson and the best of playing a Strat. I feel like I can get much more of a Gibson sound on the bridge pickup of a Blackguard than a Strat.

The Tele bridge pickup changed from flat to staggered polepieces in late ’55, and I’d put the flat pole Blackguard bridge pickup up against a PAF any day

“But then you might say, ‘Why don’t you play a Gibson?’ Well, I don’t feel like I can get the same finesse out of a Gibson. Blackguards just have such a unique and agile sound.

“There are a lot of people who love those old controls, too. When it comes to the original circuits, with the switch in the back position, it allows you to blend in the neck pickup [with the bridge pickup] using the tone knob. There’s no tone cap involved. You can go from all bridge and then blend in the neck.

“I pretty much always keep the bridge pickup wide open, but there are people who like it in between. It’s really very subtle – maybe subtler than people imagine – but I think it adds more low-end and mids.

“The middle position is just the neck pickup with no tone adjustment whatsoever, and the forward position cuts out all the highs and is very muted. That was Leo’s idea to cater to jazz musicians. And to use it as a bass sound. When the Broadcaster came out, there was not an electric bass yet – he invented that the next year!”

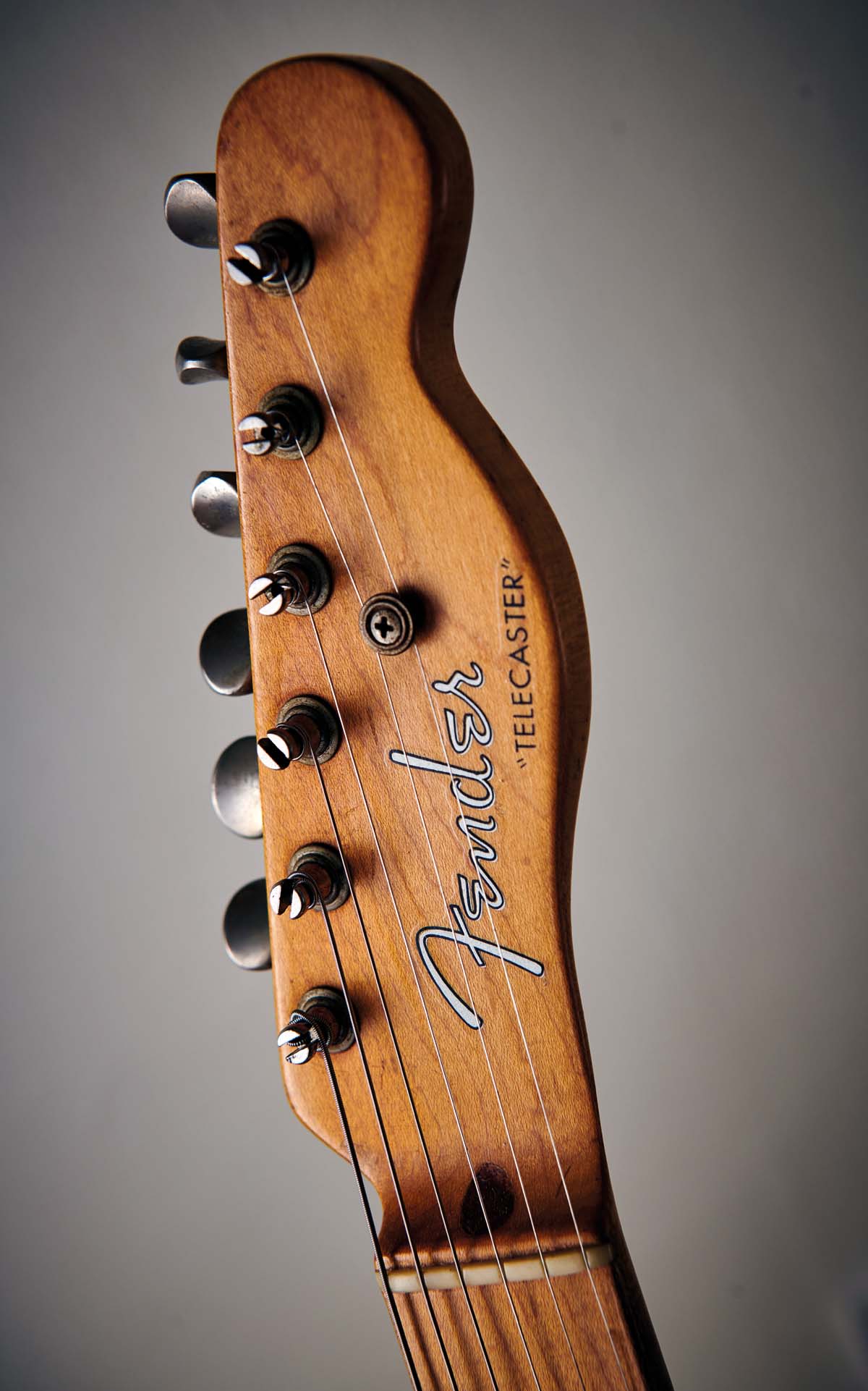

Later in spring 1951, Fender unveiled its rebranded model: the Telecaster, the name conceived just days after Gretsch objected to the Broadcaster name.

In early 1951, following a trademark objection from Gretsch, Fender briefly omitted a model name from the headstock, thus giving rise to the term ‘Nocaster.’

Although the dark-sounding front-position ‘jazz tone’ remained, in 1952 the Telecaster’s electronics were modified to include a regular tone control/knob with the neck and bridge pickups individually selected in the middle and rear positions respectively.

This design remained standard for Teles up until 1967 when it was changed to the more familiar format where the neck, bridge and both pickups are selected in the front, rear and middle positions respectively, with all three positions featuring a regular tone control.

Despite such changes, however, the Telecaster’s essential design has remained faithful to its original Blackguard incarnation up to the present day.

“I think the Telecaster’s success over the years is down to its simplicity,” concludes Richard. “They got a lot right from the get-go. Some of it was by genius and some of it was by luck. There were some really crazy ideas in the design – like the idea they could make a separate body and neck and just swap it out with some bolts.

A lot of it sprang from the initial conversations with musicians that were along the lines of, ‘I want a solidbody that’s not going to feed back like crazy at high volumes’

“That’s still used in pretty much every Fender guitar today, as are the pickups. Leo got a lot right. It was a case of, ‘I have a pickup that works great in a lap steel, so let’s use that.’

“The bridge plate was a new holding mechanism to keep the pickup in place, and it allowed adjustment of string distance. The very earliest ones have a steel plate on the bottom that would later change to brass [in 1951], and some of them are potted differently.

“I think a lot of that change was them trying to see what would work well in this new form factor of a solidbody guitar. A lot of it sprang from the initial conversations with musicians that were along the lines of, ‘I want a solidbody that’s not going to feed back like crazy at high volumes.’ The story of the Blackguards is really interesting.

“My understanding is all this started with a meeting between Les Paul, Paul Bigsby and Leo Fender. Les Paul was saying, ‘All these hollowbodies feed back too much. I would really like a guitar that doesn’t have this problem of so much feedback when I play live.’ They were brainstorming over a solidbody guitar and Bigsby built a few. But he really didn’t go commercial with it. Leo took it from there.”

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.

“It combines unique aesthetics with modern playability and impressive tone, creating a Firebird unlike any I’ve had the pleasure of playing before”: Gibson Firebird Platypus review

“This would make for the perfect first guitar for any style of player whether they’re trying to imitate John Mayer or John Petrucci”: Mooer MSC10 Pro review