The genius of Charles Mingus: activist, writer and jazz legend

Mingus biographer Dr Nichole Rustin-Paschal offers an academic perspective on the musical legacy of one of the most iconic figures in jazz history

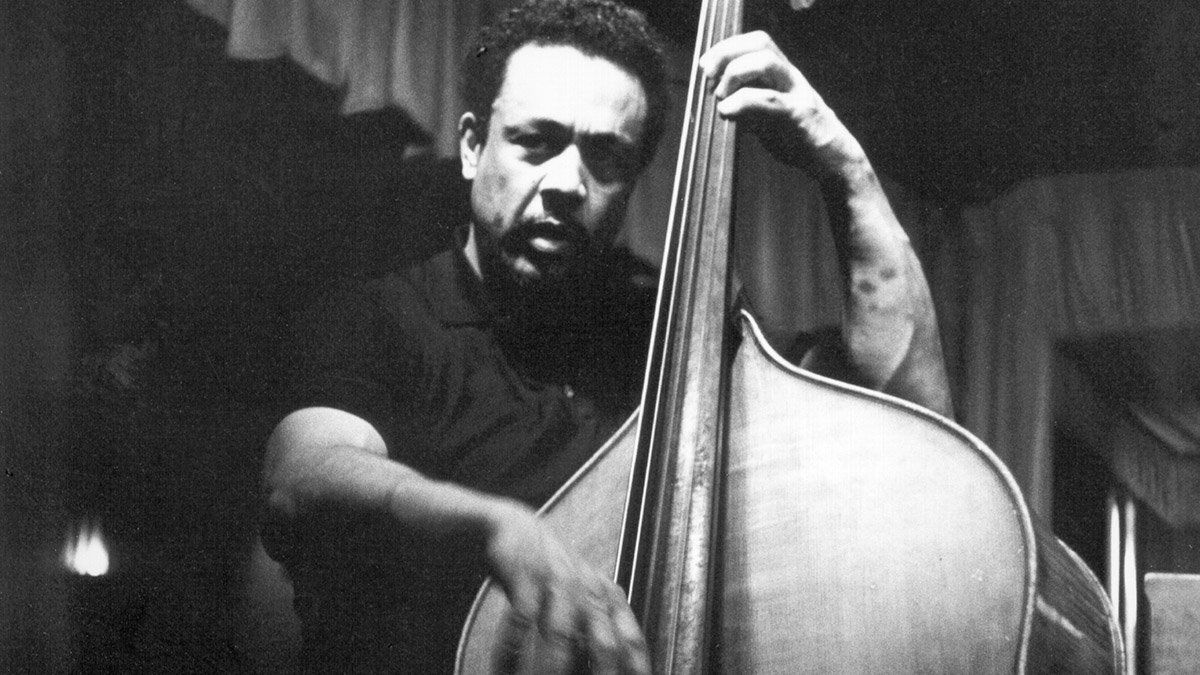

My favorite photo of Charles Mingus is of him sitting at his piano, wearing an animal print, silk-dressing gown. He holds the phone in his left hand, elbow resting on the piano.

As he talks, he smiles, and his right hand is slightly blurry, caught mid-motion. Mingus looks here like a movie star, raven haired, mustached, and goateed. Lida Moser took the photos in 1965 in Mingus’s New York City apartment.

In another photo from that shoot, Mingus, still enrobed in his dressing gown, stands bowing his bass. Moser’s use of a long exposure visualizes the ecstatic feeling Mingus often commented he felt while playing. The blurring of his bowing arm and the over-exposure of light on the side of his face, itself slightly blurred, gives the sense of his being enraptured.

“Charles Mingus, a musical mystic, died in Mexico, January 5, 1979, at the age of 56. He was cremated the next day. That same day, 56 sperm whales beached themselves on the Mexican coastline, and were removed by fire. These are the coincidences that thrill my imagination.

"Sue, at his request, carried his ashes to India and finding a place at the source of the Ganges River, where it ran turquoise and glinting with large gold carp, released him, with flowers and prayers at the break of a new day.

"Sue and the holy river will send you to the saints of jazz – To Duke and Bird and Fats – And any other saints you have.”

Joni Mitchell, from the liner notes to Mingus (1979)

My second favorite photo, perhaps taken by a family member around the same time as the Moser photos, finds him reclining in a black leather chair, barefoot, engrossed in editing a draft of his manuscript for Beneath The Underdog.

He holds a few pages and pencil in hand. Beside the chair is a barstool piled with the bulk of the manuscript. Mingus began Beneath The Underdog in the mid-1960s, around the time the Moser photos were taken.

On the other side of the chair is a bookcase overflowing with albums, books, papers, and other things of life. His bass leans against the bookcase, its broad back facing outward.

At the foot of the chair is a chessboard, game in mid-progress. In another photo from this shoot, Mingus sits at the edge of the chair, looking with bemusement at his toddler who smiles directly at the camera.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I love these photos of Mingus relaxed, in good humor, surrounded by family life, music, and writing. Too often, when we seek stories of Mingus’s life, we are bombarded with anecdotes about his volatile temper, threatening leadership, and demanding compositions.

And yet, as these photos suggest, Mingus also brimmed with humor, tapped into the spiritual elements of music, and enjoyed quiet reflection as well as family life.

Mingus was among a small number of jazz autobiographers whose approach to writing about the jazz life focused less on the minutiae of life on the road, than they did on exploring the experience of race, gender, and music.

This side of Mingus is as important to our understanding of his life and music as are the tales of his ferocity on and off stage. Understanding that fullness of his humanity allows us to understand Beneath The Underdog as the multifaceted record of that life as he intended it to be.

Mingus was among a small number of jazz autobiographers whose approach to writing about the jazz life focused less on the minutiae of life on the road, than they did on exploring the experience of race, gender, and music through complex and often unreliable narration.

Louis Armstrong, Mezz Mezzrow, Billie Holiday, Hampton Hawes, Art Pepper, Lena Horne, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Horace Tapscott, and Miles Davis are a few of those whose stories come to mind.

Like these musicians, Mingus pushed boundaries when recounting his experience and his understanding of how being a black man in the U.S., when fighting against segregation and prohibitions on interracial intimacy, demanding the ability to freely exercise civil rights, and negotiating the politics of the Cold War.

Beneath The Underdog, criticized at the time of publication as skirting the line of pornography and saying little, if anything, about “the music”, remains a challenging and rewarding document of Mingus’s thinking, including that of how he understood jazz as inextricably tied to emotional expressivity, the struggle to be respected as a black man and creative thinker, and the demands of providing for a family and bandmembers.

Mingus frames this exploration of his psyche and life as a session with a psychologist. His strategic confessions to the psychologist challenge our conceptions of black male desire, spirituality, sexuality, relationships, and a relentless searching that found expression in his compositions.

Black Saint And The Sinner Lady is one such composition. With liner notes written by Mingus’s actual therapist, Edmund Pollock, the album was an antidote, Mingus claimed, to the social ills confronting the country. Pollock agreed, musing that what he heard on the album was a plea “to unite in revolution against any society that restricts freedom and human rights.”

Released in 1963, the album also documents Mingus’s evolving approach to arranging and composition. He used the piano as “musical score paper” to communicate with the musicians the emotional ideas he wanted them to express.

He explained that this was so musicians would “learn the music so it would be in their ears, rather than on paper, so they’d play the compositional parts with as much spontaneity and soul as they’d play a solo.”

While he was generally pleased with their ability to do so, as he observed in his own notes for the album, he thought Jaki Byard missed the mark on one of the sections, and so he played the passage himself and it was later cut in during post-production. There are few recordings of Mingus playing the piano, but his 1964 album, Mingus Plays The Piano, is a standout, showing how skillful he was on the instrument.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Mingus was expanding his approach to composition. Though he’d been performing and composing since he was a teenager, he began to feel the need, he said, to come out from under the shadow of his idol, Duke Ellington.

After a disastrous first time touring with Ellington earlier in his career, Mingus found redemption in Money Jungle, which he recorded with Ellington and Max Roach. A flurry of Impulse!, Candid, and Atlantic recordings showed the reach of Mingus’s ideas about jazz, politics, and traditional forms of black religious and cultural expression.

While he resisted the labeling of his music as jazz, reflecting his belief that black musicians and composers were pigeonholed because of racism, he nevertheless insisted that what he composed was inextricably linked to black culture. As he said, “Jazz is still an ethnic music, fundamentally... jazz is still our music.”

Mingus often challenged the racial politics of jazz culture and the music industry, as well as critiquing the absurdity of segregation and segregationists like Governor Orval Faubus. He understood himself as a black man in a white world.

He advocated for musicians to be well compensated and recognized for their music. Mingus was a self-described “jazz political activist”.

Through efforts such as his Debut record label and the Jazz Composers Workshop, Mingus sought ways to take control of his music and to make space for other musicians who deserved the chance to be heard, showing how much jazz is a collective and individual effort.

Mingus was fiercely loyal to his musicians and collaborators, including Dannie Richmond, Eric Dolphy, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, and Charlie Parker. So much of what he understood about what it means to be an artist, to be a friend, to be a caretaker, he learned growing up in Watts and performing on Central Avenue.

He proudly continued playing the “simple West Coast colored no-name music” of his youth. Lifelong friends like Buddy Collette understood how important it was to Mingus to be in creative community, to have freedom of expression, to belong and be cared for.

Mingus cultivated a worldview that favored emotional honesty, an ethic of care and encouragement, and the provision of musical safe spaces, where experimentation, professionalism, discipline, and dreams were nurtured. Though he spent half of his life living in New York, Mingus never abandoned that idealism about what the music represented.

And now we get to celebrate the centenary of this incredibly complex and generous musician and composer, who understood that through his music he would live eternally.

He has always invited us into his world, where we have the space to imagine freedom, to contemplate love in all its mystery, to laugh and to cry. As Lida Moser and the unknown family photographer captured the multiplicity of Mingus’s personality, let us remember him. Let our children hear his music always.

- Dr Rustin-Paschal’s The Kind Of Man I Am: Jazzmasculinity And The World Of Charles Mingus Jr. is published by Wesleyan University Press.