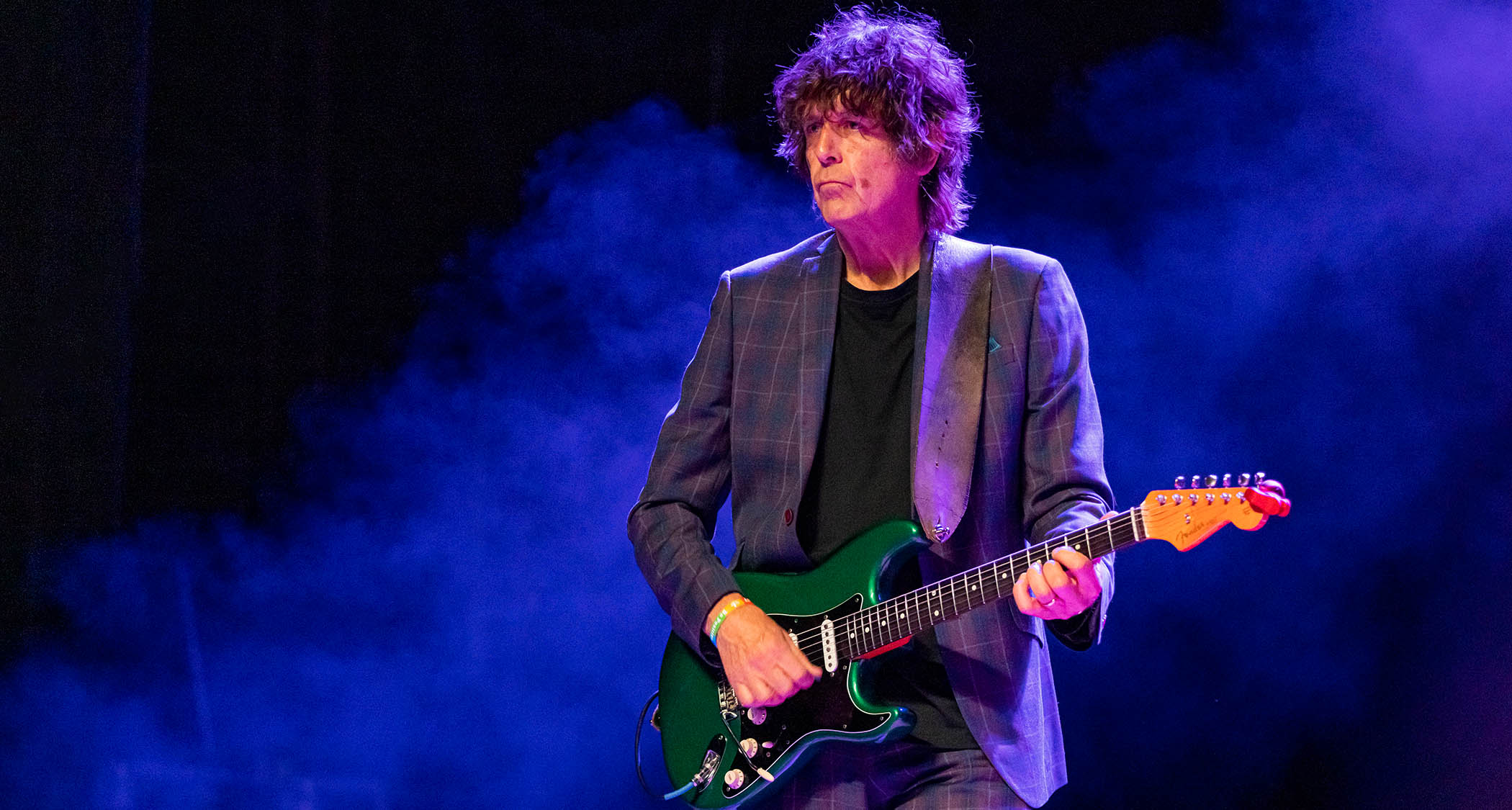

“Mick Ronson was the guitarist prior to me. He was one of my heroes, so when I joined that band I had some pretty big shoes to fill”: The Fixx’s Jamie West-Oram on his journey from distorted rocker to new wave guitar hero – and why he's big on Suhr

Four decades ago, the British new wave band the Fixx were having their moment in the sun. Hooky, slick and multi-textured hits such as Red Skies, Saved by Zero, Stand or Fall, One Thing Leads to Another and Deeper and Deeper turned the group into radio and MTV darlings.

By the degree that success in the music industry is measured (platinum sales for 1983’s Reach the Beach and gold for its 1984 follow-up, Phantoms), it appeared as if the Fixx had it all nailed down.

By the end of the ’80s, however, things began to trend downward; the band’s last charting single of any significance was Driven Out, in 1989. But that doesn’t mean the Fixx’s music went away; in fact, over the past two decades it’s reached new – and perhaps larger – audiences than ever before, via TV ads.

Toyota and Fidelity Investments have run spots utilizing Saved by Zero, and the human-resources company ADP seized on the funky dance rhythms of One Thing Leads to Another to tout the synergistic effects of their data-driven insights.

“It’s a very funny thing, the way those ads hit people,” says Jamie West-Oram, the band’s longtime guitarist.

“One of the bigger ones was when Saved by Zero was used by the car company to promote its zero-financing deal, which certainly wasn’t what we had in mind when we wrote it. Some hardcore Fixx fans were like, ‘How could you let them do that?’ But it’s just music, you know? Let’s not get too upset about it.”

He chuckles, then adds, “Whenever I hear one of our songs on TV or the radio or wherever, I feel somewhat amazed. The fact that we’re getting recognition after so many years is a nice feeling.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Interestingly, while the Fixx were racking up hit after hit in the U.S., they got the cold shoulder from the music press and record buyers in their homeland; their highest-charting album in the U.K., Reach the Beach, stalled at number 91 (versus the U.S., where it enjoyed Top 10 status).

“We were grateful for success anywhere we could find it,” West-Oram says. “We started out in London and built a bit of a following, but before we knew it, things started happening for us in America.

“MTV picked up on us, and then we got on a tour with the Police. They were at their peak with Synchronicity, and we opened up for them at stadiums. It was strange. As we kept having more and more success in the States, it became harder and harder for us to get gigs in the U.K.”

The band’s lineup has remained remarkably stable – along with West-Oram, who joined in 1980, it includes founding members Cy Curnin (vocals), Adam Woods (drums) and Rupert Greenall (keyboards). Bassist Dan K. Brown, who signed on during the Reach the Beach sessions, split in 1994 but returned a decade later.

“We had a very brief hiatus somewhere in the ’90s,” West-Oram says. “We were thinking, ‘Is that it?’ I thought it was over, but eventually Adam said, ‘Hey, don’t we want to do some more?’ That’s all it took. We gave the band another shot, and we’re still here.”

Leslie was definitely an inspiration on Knuckle Down. That’s how I started out, really – loud and proud

The classic lineup has recorded a couple of albums since regrouping (2012’s Beautiful Fiction was followed by 2022’s Every Five Seconds), and on each record West-Oram’s identifiable guitar sound looms large: elegant, understated riffs and leads, captivating soundscapes, and rhythm playing that alternates between super-slinky and rock steady, all of it filtered through a judicious and creative application of effects.

All of this and more is front and center on the guitarist’s first-ever solo album, 2023’s Skeleton Key, an engaging, mostly instrumental affair (he sings lead on four tracks) on which he makes maximal use of artful minimalism. There are some unexpected detours, however, most notably on the striking single, Knuckle Down, which sees West-Oram paying tribute to one of his heroes, Leslie West, while reclaiming his pre-Fixx blues-rock roots.

“Leslie was definitely an inspiration on that song,” he says. “That’s how I started out, really – loud and proud,” he says. “I loved a lot of blues and rock guitarists. I played with a fellow named Phillip Rambow. He had a great band that included Mick Ronson; he was the guitarist prior to me.

“Mick was another one of my heroes, so when I joined Phillip’s band I had some pretty big shoes to fill. That’s where my head was at then, being a bit bluesy.” He laughs. “With the Fixx, I had to try something different.”

How did you come to re-engineer your guitar sound with the Fixx?

“I suppose it was somewhat gradual. I went to music college in Leeds and learned a lot about chord structure. Everybody was playing quite fast at that time, but then punk happened and things started to change. I moved to London and realized that all you needed were two or three chords and lots of energy and attitude.

“I showed up at an audition with the Fixx wielding an old Les Paul Junior with one pickup. I plugged it straight into a Marshall and cranked it to 11. That was my sound. When we signed a publishing deal, I bought an MXR Stereo Chorus, and then I realized I needed two amps. I bought another Marshall – and I had my stereo sound.”

“One of the first recordings we did with [producer] Rupert Hine was a song called Some People. I heard a part that needed this… how do I put it? It was a ‘chang’ sound I heard. I didn’t have the right kind of pedals at my disposal, so I switched my amp to a clean setting.

“Through my headphones, I could hear our engineer, Steve [Stephen W. Tayler], playing with the sound. He put it through a Roland Dimension D and compressed it. I went, ‘Ahh! That’s interesting.’ That was when I started to want to get some pedals. The band got on me a bit – ‘We don’t always want harsh, dirty sounds. We want clean sounds.’ I rebelled at first, but then I saw the sense of it.”

Around this period, synths were taking over. Did that have something to do with how you approached guitar parts?

“Sure. The Fixx had a very creative keyboardist, Rupert Greenall, who was a mad genius at sculpting sounds. I had to find a way to fit lines and licks in with what he did, so sometimes less was more. He’d play something and I’d respond, or sometimes it was the other way around. We formed a great dialogue, the two of us.”

A few years before the Fixx hit, guitarists like Andy Summers and the Edge had changed the landscape for the use of effects. Were they an influence on you?

“I think we were all doing that at the same time, although I greatly admired those two players. I suppose they did influence me. That ‘chang-y’ thing I mentioned, it could have come from them, but it also could have been Keith Levene from PiL.”

We hear that “chang-y” thing in those punchy chords on One Thing Leads to Another. Was your rhythm riff the basis for the song?

“It didn’t start out that way. The whole thing was written quite quickly in one rehearsal during a jam. Cy kept singing “one thing leads to another,” and I was playing around with it. I liked ska, but I was also listening to the Talking Heads and Nile Rodgers.

“I always admired Nile’s guitar playing, so I suppose he was an influence. I wanted something choppy, and I searched for the right pocket – pushing here, pulling there. Eventually, I just kept strumming.”

The song became a huge dance hit. Were you surprised?

“We were. We thought it was a great song, but that doesn’t mean it would be a hit. It was overwhelming to us how well it was received.”

You guys recorded Deeper and Deeper for the 1984 film Streets of Fire. How did that come about?

“That was pretty funny, actually. Cy and I were living on the same apartment block in New York at the time. One morning I got a call from him – ‘Quick. You’ve got to come over right now. [Soundtrack producer] Jimmy Iovine will be here in half an hour.’ Cy had forgotten that he’d set up a meeting with Jimmy to listen to the song we’d written for the movie, which we hadn’t written ’cause he forgot. [Laughs]

“In half an hour, we wrote Deeper and Deeper and banged it down on a PortaStudio. We had a drum machine, so Cy laid down a bass part and I did a guitar part. We somehow came up with lyrics, and there it was. Jimmy came over and he loved it.”

On the finished version, it sounds like you’ve got three guitar parts darting around doing various things. Am I hearing it right?

“You probably are. I haven’t listened to the track in a long time. I probably should.”

That song and others, like Saved by Zero, have very understated riffs that are absolutely essential. Did they pop right into your head? Trial and error?

“I suppose it’s like fishing; you’re waiting for something to happen. It’s partly a construction process, but in the end you surrender yourself to surprise. Some things just come out of the blue.”

You started out on Gibsons, but with the Fixx you switched to John Suhr Strat-shaped models. (Also, as discussed in the May 2019 installment of GW’s Tonal Recall, West-Oram played a Strat-style Ibanez Blazer BL-100 on One Thing Leads to Another.)

“I had gone to a club one night with Adam, our drummer. A jazz-fusion band was playing, and they had a killer guitar player named Adam Murphy, who sadly is no longer with us. He was playing a Strat, and I said to someone, ‘How does he get that sound out of that Fender?’ The person said, ‘It’s not a Fender. It’s a Schecter.’

“A few months later, I was in New York and I went to Rudy’s Music. John Suhr was the guitar tech. There were quite a few guitars he’d put together from Schecter parts. I thought they were beautiful. I tried out a few, and John said, ‘I’ve got one you might like.’

“He showed me this brown guitar, and I loved it. John had put it together. Later on, John went to work for Fender, and then he started his own successful guitar company – Suhr Guitars. He built me a replica of the brown guitar, which I played the hell out of. I use it on every tour.”

During the ’80s, did you rely on just a few pedals, or did you have one of those big Bradshaw rigs?

“At first I had a few pedals taped to the stage. It was a primitive setup, really. Eventually, I had to get more professional, so our stage manager built a rack for me. He took the heads out of two Marshalls, put those in the rack, and somebody else put the innards of my pedals inside. I had the MXR stereo chorus and an MXR Dyna Comp, which was replaced by a Valley People Dyna-mite. I also had two Rat distortions; I think that was it.”

I recorded it during the pandemic. I have a fun wife, a garden and a shed full of recording equipment. I thought, 'I’ll record tracks and see what happens'

Let’s talk about Skeleton Key, your 2023 solo album. Why so long to do one? It’s been 40 years!

“Yeah. I recorded it during the pandemic. I have a fun wife, a garden and a shed full of recording equipment. I thought, 'I’ll record tracks and see what happens.' I recorded everything at home except for the live drums.

“Nick Jackson, who produced two tracks on the last Fixx album, has a great home studio, so we did the drums there. Nick and I co-produced the album. He’d listen to tracks and go, ‘A list, B list, dump it.’”

Knuckle Down has these funky, slinky guitar lines – classic Jamie stuff – but then you go into some bruising rock.

“My goal on that one was to create something that makes use of space, so you have the funky thing with strategic spots of nothing, and yeah, then it takes off into the heavier bit.”

Talk to me about how Leslie West informed your playing for the heavier section.

“I always loved Leslie’s beefy sound. I was taken with the whole concept of the band Mountain; you had Leslie’s big, bellowing sound mixed with Felix Pappalardi’s falsetto. They were heavy yet mystical. Leslie was kind of why I bought a Les Paul Junior back in the day. I’m known for clean sounds, but I do like dirty sounds, and Leslie was just incredible in that area. He was an inspiration for the dirty sounds.”

I always loved Leslie’s beefy sound. I was taken with the whole concept of the band Mountain; you had Leslie’s big, bellowing sound mixed with Felix Pappalardi’s falsetto

Cuckoos in the Nest has a real nod to Sixties psychedelia. Am I in the right lane?

“Yeah, I think. That wasn’t the plan, but it was the end result. That track is about irrational fears and how our minds are polluted by unnecessary negative thoughts. If we think about it, we can just go, ‘Fuck off. I don’t need negativity.’ I guess the psychedelic vibe carries that across.”

Your singing on the record is very strong and emotive. This is something you’ve kept under wraps over the years.

“I don’t pretend to be a proper singer, but I do background vocals with the Fixx. I like singing in the car or the shower. This album was going to be all instrumental, but Nick encouraged me to sing on a couple of songs. It’s a guitar player throwing in a few vocal tunes. Hopefully, I’ll get away with it. [Laughs] I’m not bothered by whatever anybody says.”

At the time of this writing, the Fixx are getting ready to tour the States. At this point in your career, do tours feel like celebrations of your past? It’s not like you have anything to prove.

“I suppose that’s the case. I think with each tour, we just want to get it right. [Laughs] I mean, we get it right, but we want it to be better. We discover something new in the old songs all the time. At this point, we’ve got hundreds of songs to choose from, but we’re not one of those bands that won’t play the hits.

“That would be crazy! We’re lucky to have had one hit, let alone several. If I saw the Stones, who I’ve never seen, I’d want to hear them play Jumpin’ Jack Flash. I’d be disappointed if they didn’t play it. You have to make sure the audience has a great time. That’s what it’s all about.”

- Skeleton Key is out now via BFD.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.