The bass guitar summit: Dave Swift meets Juan ‘Snow Owl’ Garcia-Herreros

Jools Holland's in-house bassist Swift and the Grammy-nominated Snow Owl talk career paths, Jaco and gear

The bass guitar summit is where we bring two amazing bass guitar players together to discuss the pleasures and pitfalls of life at the low end.

This month, it’s Jools Holland’s long-time bass player Dave Swift and the Grammy-nominated Colombian bassist Juan ‘Snow Owl’ Garcia-Herreros, revealing how they built their unique careers.

Dave Swift: “You arrived in New York from Colombia in 1984 – is that right?“

Snow Owl: “That’s correct, in early 1984. I was eight years old.“

DS: “And was that when you saw Jaco Pastorius, who was homeless at the time?“

SO: “Yes. It’s a very sad story, and it’s always hard to tell it. My mother was working at a store near the Blue Note, near the Washington Square park, and she asked me to give out flyers to promote the store. I was walking in the park and there was a guy there with a bass and a cassette player.

“He looked like he’d been sleeping there. He was screaming ‘I did this music. Do you hear this music? That’s me!’ He was boasting about how great this music was, and saying how he was the greatest bass player that ever lived, and asking people for money.“

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

DS: “That must have been upsetting.“

SO: “For a child, it was intimidating, I won’t lie. It was heartbreaking, and I felt so bad for him that I walked up and gave him some money. And then 20 years later, I was the bassist for the Jaco Pastorius Big Band, and while I was researching Jaco’s life in preparation for that gig, I met the writer Bill Milkowski and we talked about him.

“In Bill’s book about Jaco, there is a part where he talks about Jaco being in that park. I don’t know how to describe the moment when I read that part. I literally dropped the book in shock, and I started crying. Even right now, when I think about that, I’m heartbroken.“

DS: “That’s so sad. I was also in New York in 1984, because I was working on the QE2, the cruise ship. We were going backwards and forwards from Southampton. I knew who Jaco was, but I didn’t know his situation. It’s funny to think that you and I might have passed each other in the street.“

SO: “It wouldn’t surprise me, because that situation has happened to me so many times. Did you ever go to Manny’s music store and pick up a copy of the [infamous unofficial jazz reference work] Fake Book?“

DS: “I did. You had to buy them under the counter, literally, in a brown paper bag. The procedure was most surreptitious.“

SO: “They made me say a special password before they would sell it to me!“

DS: “There is a purist theory which says that any self-respecting jazz musician shouldn’t need the Fake Book. It’s like using cheat sheets. The jazz greats that we aspire to be like all learned the songs by ear. One of the things you need if you want to get hired is a vast repertoire of songs from every genre.“

SO: “Exactly. I learned through the school of hard knocks. I used to go over to Mick’s Pub in Harlem for jam sessions, and those were a great school if you wanted to learn jazz, but if you showed up with the Book, the rest of the house band would change the keys on you, just to teach you a lesson.“

“They way I did it was by learning from piano players that I used to gig with. They would call a tune, but only tell me the first chord so I had to figure out the rest by ear. I embarrassed myself a few times!“

DS: “The best lessons that I’ve learned in life, musically and otherwise, have been under the most awkward and embarrassing circumstances, when you get caught out for not being fully prepared or fully qualified. This is when you grow, exponentially.“

SO: “Absolutely. For me, my boot camp was when I started playing bass in 1992, at the age of 15, after my brother, who was a drummer, told me that he needed a bass player. I was in Florida back then, and access to jazz music was very limited. Radio stations would only play jazz at two o’clock in the morning, but I would record them on cassette and transcribe the parts.“

DS: “Absolutely. Transcription is so important for us as bass players.“

SO: “I don’t know how many cassettes I broke, but I was blessed by getting my ass kicked so many times. Basically half of Duke Ellington’s touring band, as well as musicians like Nat Adderley, all retired to Florida, and you could jam with them if you were prepared to drive hours to get there. When you saw how those guys knew the tunes, and how they would call them out, they swept the floor with me every night, and that’s what made me love the discipline.“

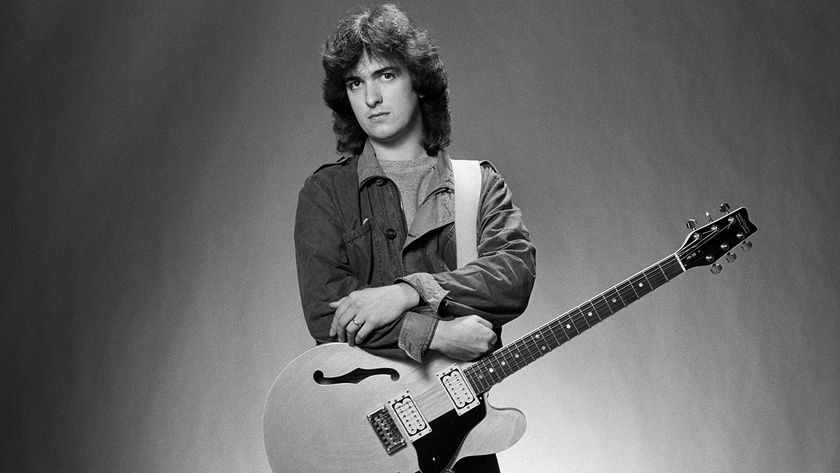

DS: “Like you, I started out on a different instrument – in my case, the trombone, which was just a bit of fun. I was more interested in sports and horror movies than being a musician. My teacher, Phil Johnson, fought for me to study with him, even though I was thought to be too old at the age of 14. Without Phil, I wouldn’t be here. You also play trombone, I believe?“

SO: “Yes, because salsa music is a huge part of our folklore in South America. The original salsa bands were one trombone, one violin and a montunos, which is a guitar with three courses of two strings. All my life I wanted to be in one of those bands. Trombone and flute were my instruments before I started on bass.“

DS: “Funnily enough, it was trombone that got me into bass. I was watching Top Of The Pops one night, looking for any trombone players, and I noticed that the bass players on there weren’t doing anything that seemed very difficult, although it definitely looked cool.

“That all changed when a friend of mine told me to listen to Weather Report’s Night Passage LP, because I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I thought ‘This is impossible. How is this guy doing this?’ And that album is not a particular favourite among Weather Report fans, but for me it’s key, because it was the first time I heard Jaco.“

SO: “There’s just so much stuff going on in those songs. Synth, fretless bass and so much other instrumentation – it’s mind-blowing.“

DS: “And then right after that, I got into Stanley Clarke, who was important to me because he also played upright bass.“

SO: “Did you first hear Stanley on the upright, or on electric with Return To Forever?“

DS: “I heard him on his own albums before I heard Return To Forever. Anthony Jackson was a huge influence on me too. It’s funny that you and I are both predominantly six-string bass players. Which bass players influenced you?“

SO: “The first bassist who really blew my mind was Cliff Burton of Metallica, whose music I really studied. There was one store that had a tab transcription of the Ride The Lightning and Master Of Puppets basslines, and that – plus the cassettes – was all I had, because I didn’t have MTV. I studied his song Orion, and his famous bass solo Anesthesia, which made total sense when I later got into Jaco’s distorted stuff.

“For me, they were the same world. Those two guys were thinking in the same direction. So Cliff was my introduction into how bass could be powerful, but the bassist who swept me off my feet after Cliff was John Paul Jones. He was the glue between Jimmy Page and John Bonham, while being so melodic and musical.“

DS: “You studied bass at Berklee. How was that for you? I didn’t go to college myself, and I wondered if institutionalized studying was rewarding for you.“

SO: “Like you, I’m a self-taught musician. I was lucky in high school because I didn’t have the money to rent an electric or acoustic bass, but the band teacher was kind enough to let me sneak into school at night so I could practice.

“I worked my ass off, in that room by myself, to win a scholarship to Berklee, because that was my only way of getting in. I could never have paid for it myself. I won’t lie to you, it was like two years of insomnia, but it was worth it because the blessing came and I got the scholarship in 1995.“

DS: “Did you complete the full course?“

SO: “No, I did only the first two semesters, although I could have gone on to do the four years. My teacher, Bruce Gertz, said to me ‘Juan, you have the discipline, the passion and the focus. You don’t need school. Go and make a career.’ He gave me a list of all the books I needed, and told me to go to New York and develop myself.“

DS: “I wrote off for the Berklee prospectus in the late-'80s because I was interested in studying there, but when I saw the high cost of the fees, I decided that permanently moving to London and taking lessons with prominent players and teachers was a more financially realistic option.“

SO: “Absolutely correct. You’re the perfect example of this. As a school curriculum has to suit a general amount of people, it cannot be individual – and most of all art is about the individual. The development of an artist, and the artist’s voice, and the stubbornness when you say ‘I played that note because it’s me’ is individual. The schools cannot develop individuals, although they can give you the fundamentals and the history.

“When it comes to giving you an individual voice, they fail tremendously. I was a professor at the Institute in Graz after I moved to Austria from New York, and I ended up being thrown out for that exact same philosophy, because I challenged all of them in a meeting. I said to them, ‘This school has not produced one successful, original artist in 60 years.’“

DS: “What made you move to Austria? For me, New York was the ultimate place to be for music. It’s such a melting pot of creativity.“

SO: “Yes it is, but remember, there are two New Yorks – the one that everybody dreams about, and the real one. I gave 16 years of my life to New York City, and I worked with some of the most unbelievably famous geniuses of their instrument, but in wedding bands, just to get by. It was bizarre. Philosophically, it went against everything I believed in.“

DS: “Still, presumably you did a lot of good work when you lived there?“

SO: “Oh yes. I was in my twenties back then, so on a normal day, I’d record jingles for a few hours in the afternoon, or pop songs or whatever, and at night I’d play a Broadway show. After that I’d go to a jam session.

“But after a few years the studio work went away, the shows got unionized, which made things difficult, and then jazz turned into something that the masses didn’t like enough to keep it going. And then 9/11 happened. I was literally sitting there, watching the World Trade Center burn, and thinking to myself, ‘A lot of dreams died today’.“

DS: “What was the effect on you of witnessing that event?“

SO: “Soon after that, I moved to Vienna to study classical music. It was what I’d always wanted to do, but I had got lost in being the house bassist for shows, and whatever. It was a real moment of clarity, so I saved what I could, flew to Austria, learned German and then started studying. That was the beginning of my solo career.“

DS: “What’s the most important thing that you bear in mind when you’re playing bass?“

SO: “Patience. The electric bass is a very hard instrument to hear – not everybody can hear frequencies that low. And what doesn’t help you is that every room that you perform in is an amplifier. It has difficult frequencies that can literally ruin the whole vibe of the night.“

When I first heard Jaco and Stanley, I became obsessed with their flamboyant playing styles, so it took me quite a while to go back and discover what had happened before them

Dave Swift

“Learning how to get a fantastic sound that sits right with the band and with the room took so much time for me to learn – and so much patience. There were so many nights that I got frustrated, me being a perfectionist, and patience was the lesson that became the bridge to evolving and succeeding.“

DS: “It’s the same for me, especially on double bass. It’s about respecting the tradition of the instrument and understanding its history. When I first heard Jaco and Stanley, I became obsessed with their flamboyant playing styles, so it took me quite a while to go back and discover what had happened before them. Once I did go back in time, I meticulously transcribed all the James Jamerson and Carol Kaye lines and studied them.“

SO: “That’s so important. At the end of the day, your reputation is something you should care about. It’s up to the current generation of musicians to set an example of responsibility and preparation for the next generation. The young musician will learn that reputation rests on showing up fully prepared for a rehearsal.“

DS: “I work with a lot of younger jazz musicians, such as my wife Lucy, and a lot of them have the whole tradition down. They’re way more diligent and tenacious than anyone was in my generation. Now, the bass guitar is designed to be easy to play quite well: You can get away with a lot by just playing simple things. You can’t do that with the upright bass – there’s no bluffing there. That’s an unforgiving instrument.“

I think Ibanez's upright bass could really help electric bass players make the switch to upright

Snow Owl

SO: “Thanks to you, I was recently introduced to Ibanez, and I’m now playing their upright bass. I tested it for three months and I think it could really help electric bass players make the switch to upright, if they wish to do that. It’ll help them with bowing, and to discover a different timbre of fretless sound. The potential of this instrument is endless. I took it to the engineers at Thomastik, who play for the Vienna Philharmonic.“

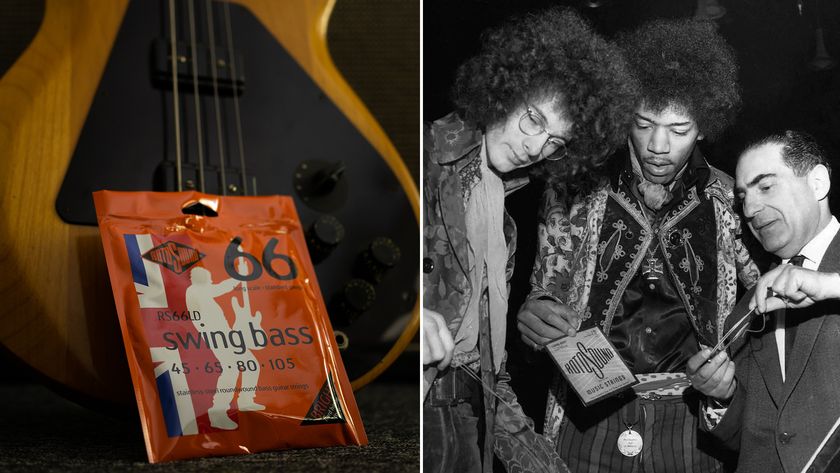

DS: “All my old P-Basses have Thomastik Jazz flats on them. They sound incredible.“

SO: “They really do. We asked ourselves how we could make it sound more real than the standard electric upright. I drilled through the body to make a through-body setup, and used spiral-core strings, and the result is that you can bow on an electric instrument without freaking out the pickups.“

DS: “When I heard you play that thing, I thought, ‘Man, that sounds like a real double bass’, even though it has a 34” scale, like a bass guitar. It’s perfect for electric bass players who are interested in transitioning to playing a double bass.“

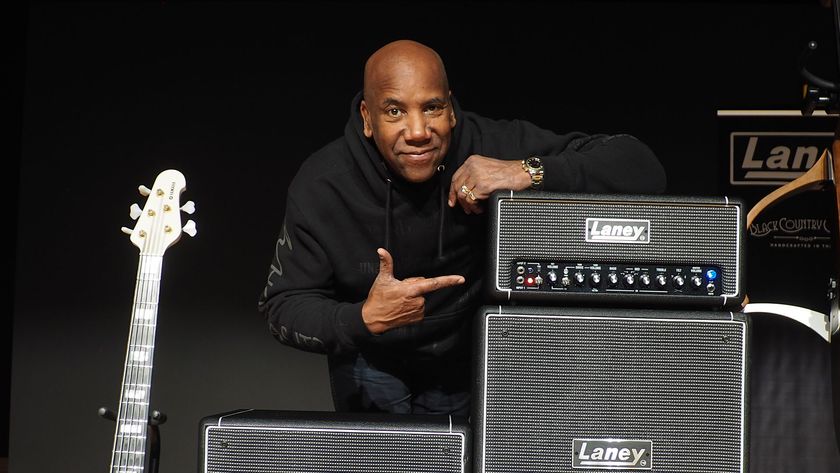

SO: “You’ve done such consistently good work with Ibanez basses over the years, rather than with a higher-end brand of instrument. Why did you choose Ibanez in particular?“

DS: “Here’s the funny thing. My first ever five-string was an Ibanez, which I got when I was working on the cruise ships in the mid-'80s. The trouble was that they’d squeezed a fifth string onto a four-string bass, so the spacing was around 15mm – but there were so few five-strings around that I had to play it.

“Back then I had to play a lot of slap stuff, because it was expected, and it drove me crazy because the spacing was so tight. I moved into a Music Man Cutlass with a graphite neck, and I didn’t come back to Ibanez until around 2013, when I bought a Musician bass and loved it. After that, I became obsessed with collecting vintage Ibanez basses from the late-'70s and early-'80s.“

SO: “How many basses do you have in your collection?“

DS: “Around 100. It’s crazy. People used to call the old Ibanez basses ‘the Japanese Alembics’ back then. A few years ago I was on the cover of Bass Guitar magazine, holding a vintage Ibanez, and they got in touch and we built a relationship.“

SO: “Do you play any really high-end instruments?“

I have an Anthony Jackson Fodera contrabass, and it means a great deal to me, as Anthony personally set it up. It’s the only super-high-end bass that I own

Dave Swift

DS: “I have an Anthony Jackson Fodera contrabass, and it means a great deal to me, as Anthony personally set it up. It’s the only super-high-end bass that I own. My Ibanez BTB Premium six-string basses are as good as, or better than, the majority of the other brands that I’ve played. Your signature Neubauer Phoenix bass is amazing. Does it come at a high price?“

SO: “The first thing that I said to the luthier Andreas Neubauer when we designed it was ‘This has to be affordable for regular people.’ There’s a certain amount of work involved, of course, and amazing woods, but it isn’t overpriced for its quality.“

DS: “Tell us about the secret hidden pickup in the headstock.“

SO: “Haha! I get so many questions about that. The Phoenix is really hard to build. Running a cable through the truss rod to get the piezo up on the headstock is very difficult to do.“

DS: “That’s fascinating.“

SO: “Thank you, Dave. You’re an outstanding musician, and you’ve achieved so much on the instrument. It’s been a pleasure to do this.“

DS: “The pleasure is all mine, Juan. I look forward to the next time we meet.“

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.

“The ace up the sleeve of bass players around the globe since 1978”: Tobias instruments were trailblazers in the bass world. Now they’re back as part of the Gibson family

“We’ve only changed the strings one time”: Travis Barker reveals the bass he uses on everything he records