The 50 greatest guitar solos of all time

The best lead playing ever committed to record, as voted by you

40. Flying In A Blue Dream – Joe Satriani (1989)

This is every guitar teacher’s go-to exemplar for the Lydian mode. Satch’s effortless legato enhances the mode’s dreamlike quality for a sound that lives up to the title.

Everyone can learn from the way Joe uses slides, vibrato, and hammer-ons to turn a simple melody into such a powerful statement. Duplicating his shred licks is a bit more specialised.

When the song kicks up a gear at 2:38, Satch moves from Lydian to Mixolydian for more typically rock phrasing. At 3:08, he’s back to Lydian and the track regains the sensation of floating it has at the beginning.

The chord progression creates such atmosphere that the last minute and a half of the track don’t even need a melody, and Satch’s feedback effects just heighten the ambience.

39. Sympathy For The Devil – The Rolling Stones (Guitarist: Keith Richards, 1968)

The sheer stuttering unexpectedness of this solo makes it captivating. The first lick starts halfway through beat 2 (where else?), and the following phrases are spaced out unpredictably after that. Keef uses repetition effectively, and there’s a lovely sequence from 2:55-2:58 of the same idea repeated with different end notes.

A lick at 3:13 consists of just one well-placed note, later repeated with a syncopated rhythm. Slash loved this solo so much he resented being asked to recreate it for Guns N’ Roses’ cover, believing the original to be untouchable.

History doesn’t record what guitar Keef used, but a contemporary documentary shows him getting a similar tone from a three-pickup Les Paul Custom in rehearsal. The amp was probably an AC30 with bass set to zero, which explains the spiky tone.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

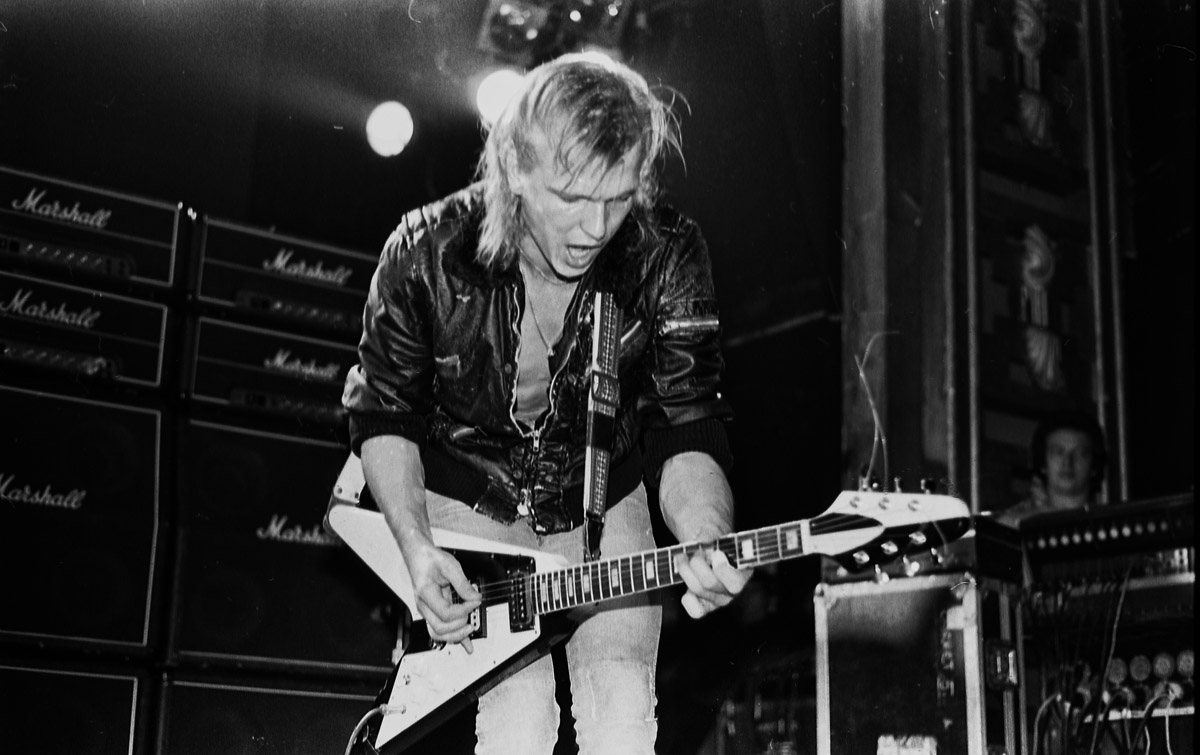

38. Rock Bottom – UFO (Guitarist: Michael Schenker, 1979)

Michael Schenker: “It was always meant to be. I had to play one long solo in my life that I could use to express myself – an extended improvised lead break, rather than the short ones I usually do. When I was with UFO making (1974 album) Phenomenon, there was a moment where I realised this was going to be that big solo for me, with a background rhythm section to build it all on.

“Then over the years from touring, I started to develop and change parts. By the time we got to [1979 live album] Strangers In The Night, it would always be different! Of course there were parts from the original, recognisable melodic pieces that were important for the song, but then I would always go somewhere else. I’ve carried on doing that through the years – using that solo as an adventure and just take off, heading into unknown territories!

“I constructed the solo by just being me, by not thinking too much and going with the flow. In the studio, I did it one way and then it started to change every night. The main parts – like the slow ascending notes at the beginning or the violining that comes after and the quick legato trills on the G string I use live to set up for what I do next.“

“That’s what gives me room for adventure and the freedom to explore what I’m feeling in the moment. And that’s why the solo has gotten longer and longer over the years! When you are on an adventure, you don’t plan anything. To improvise you have to feel and focus on what are thinking right there and then.

“And nobody knows what will happen. Sometimes it will turn out great. Sometimes maybe not so good. Sometimes exceptional! That’s the best thing about it. From the stage, you can hear the reaction of the audience when the magic happens. I’m hoping for that magic every time I play it live. We all want to know what is Michael going to do today... Even me! There’s an excitement to not knowing what is going to happen.

In my late teens I stopped listening to music, but before that it was great guitarists like Carlos, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Johnny Winter who helped me understand the guitar

“There were actually three or four notes I didn’t agree with on the live album. They sounded like mistakes to me! But mistakes can become part of the song and become important if people get used to them. After a while, they expect those notes!

“I was a bit disappointed, there were two different nights recorded for Strangers In The Night and [producer] Ron Nevison picked the Chicago version and I preferred the one from Louisville.

“Is there a Santana kind of feel at points? Absolutely! In my late teens I stopped listening to music, but before that it was great guitarists like Carlos, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and Johnny Winter who helped me understand the guitar. I was always so excited to find players like that.

“In the early days, you could probably hear my influences a bit more. But the infinite spring of creation in my world has always mutated and evolved. Now you can’t really here the influences as much – it’s more Michael Schenker than ever!”’

37. The Thrill Is Gone – BB King (1969)

Every note of this is stunning, from the barely-audible fills in verse two to King’s magnificent solos. If you’ve ever wondered how he’s so lyrical, it’s because he creates entire phrases with string bends.

Those bends offer an infinite range of pitch, BB finds sweet spots that aren’t available on the frets. Just 15 seconds into The Thrill is Gone, King spits out a lick with more subtlety and feeling than most guitarists manage in a career, topped by his peerless vibrato.

BB’s playing here is a little busier than on many of his classics, but a huge amount of it can be played using only the first two strings from B minor pentatonic position 2. With his string bending genius, BB could say everything with those four notes.

36. Cause We've Ended As Lovers – Jeff Beck (1994)

Possibly the greatest display of dynamic control ever on electric guitar. Using the guitar’s volume and varying his attack, Beck moves from clean to filthy, and from barely audible to raging.

This was before Beck became the Strat master and was recorded using his Tele-Gib, a Telecaster with humbuckers. Even without the Strat trem, Beck’s control of bends gives the main melody a lyrical quality to rival any vocalist.

The song reaches peak intensity at around three minutes, and incredibly Beck sustains this level of passion for over minute before gradually bringing things back to Earth.

The volume swells on the intro are inspired by Roy Buchanan, to whom Beck dedicated the track. Play them by plucking the note with the guitar volume on zero and quickly bringing the volume up.

35. Lenny – Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble (Guitarist: Stevie Ray Vaughan, 1983)

When the young SRV couldn’t afford $350 for the ’65 Strat he found in a pawn shop, his future wife Lenora got all his friends to chip in on it as a birthday present. The touched Stevie stayed up all night writing Lenny in tribute.

The guitar was mellower than his Number One Strat, perfect for Lenny’s extended chords and softer approach. Stevie plays with huge dynamic range in this track, using pick and fingers at different times.

The tone is essentially clean, but when Stevie picks hard you can hear it break into overdrive. It’s predominantly played with neck/middle pickup combination, but there are moments on bridge and neck pickup action too.

It’s Stevie’s use of double stops and masterful combination of major and minor scales that make it so special.

34. Walk This Way – Aerosmith (Guitarist: Joe Perry, 1975)

One of the funkiest rock tunes ever, Walk This Way’s groove is powered by Joe Perry’s incomparable swing. There are three solos, all with exciting and idiosyncratic phrasing. Perry has a reputation as a standard blues-rock player, but he tries to avoid obvious clichés. These solos are each full of slippery lines created by mixing major pentatonic and blues scales.

The first solo was played on a Les Paul Junior that also provided the rhythm tone; the others were recorded on his ’57 Strat. One of the coolest ideas comes at 2:38 where Joe plays a typical repeating lick in C minor pentatonic shape 5, starting on the G string. He then repeats the same pattern one string higher, producing a wild combination of major and minor notes.

33. Crossroads – Cream (Guitarist: Eric Clapton, 1966)

What started as a blues song known as Cross Road Blues by Robert Johnson would become one of the finest examples of natural ability, soulfulness and showmanship from the guitarist at least once referred to as ‘God’. The man in question is, of course, Eric ‘Slowhand’ Clapton, and his reimagining of Crossroads as a rock song further cemented the legacy of the virtuosic 22‑year-old.

Famously recorded at The Fillmore, San Francisco, for supergroup Cream’s Wheels Of Fire album, Clapton’s arrangement retains the soul and spirit of Johnson’s original, but updates it for a contemporary audience raring to cut loose and be entertained by dazzlingly quick, passionate musicianship.

Little did they expect, one assumes, that the four-minute track would be studied in great detail by guitar scholars and fans alike for 50 years to come.

32. Floods – Pantera (Guitarist: Dimebag Darrell, 1996)

The solo in Floods begins with a harmonic-drenched take on the main riff , featuring sus2 voicings (one powerchord stacked on top of another) making a kind of metal Message In A Bottle. Dime’s C# standard tuning helps to facilitate his jack-the-ripper vibrato, but you could play it in standard tuning (it’s in Bb minor).

Compared to other extreme metal players of the time, Dime’s note choices are more blues based. His phrasing here is closer to Slash than Marty Friedman.

Dime’s Van Halen influence is apparent in the tapping lick at 4:39. He bends up the second string and taps three frets higher, pulling off as he releases the bend. Rather than ending with a shred fest, Dime builds a devastating climax with an ascending series of unison bends.

31. Under A Glass Moon – Dream Theater (Guitarist: John Petrucci, 1992)

If you’re ever asked what shred guitar is, show your interlocutor this solo. In 59 seconds, Petrucci covers alternate picking, sweep picking,m tapping, whammy techniques, legato, harmonics, and aggressive blues scale phrasing – a near comprehensive tour of modern guitar technique in under a minute.

It jumps between C# Dorian and E Lydian, and despite some off beat rhythms it’s all in 4/4. The hard‑grooving pentatonic section should silence anyone who suggests Petrucci lacks feel.

A useful lick you can steal no matter your ability comes at 5:04‑5:06. Petrucci plays in 5ths on the first two strings (use the classic powerchord shape), and slides it between the 14th and 17th frets, playing the notes one at a time. It isn’t rocket science, but it is a great cliché buster.

Current page: The 50 greatest solos of all time: 40-31

Prev Page The 50 greatest solos of all time: 50-41 Next Page The 50 greatest solos of all time: 30-21Total Guitar is one of Europe's biggest guitar magazines. With lessons to suit players of all levels, TG's world-class tuition is friendly, accessible and jargon-free, whether you want to brush up on your technique or improve your music theory knowledge. We also talk to the biggest names in the world of guitar – from interviews with all-time greats like Brian May and Eddie Van Halen to our behind the scenes Rig Tour features, we get you up close with the guitarists that matter to you.

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo

“I said, ‘Mike, I don’t know how to tell you this, but that’s a note-for-note guitar solo from...” Mike McCready stole his Alive solo from Kiss – but Ace Frehley had already stolen it from another legendary classic rock band