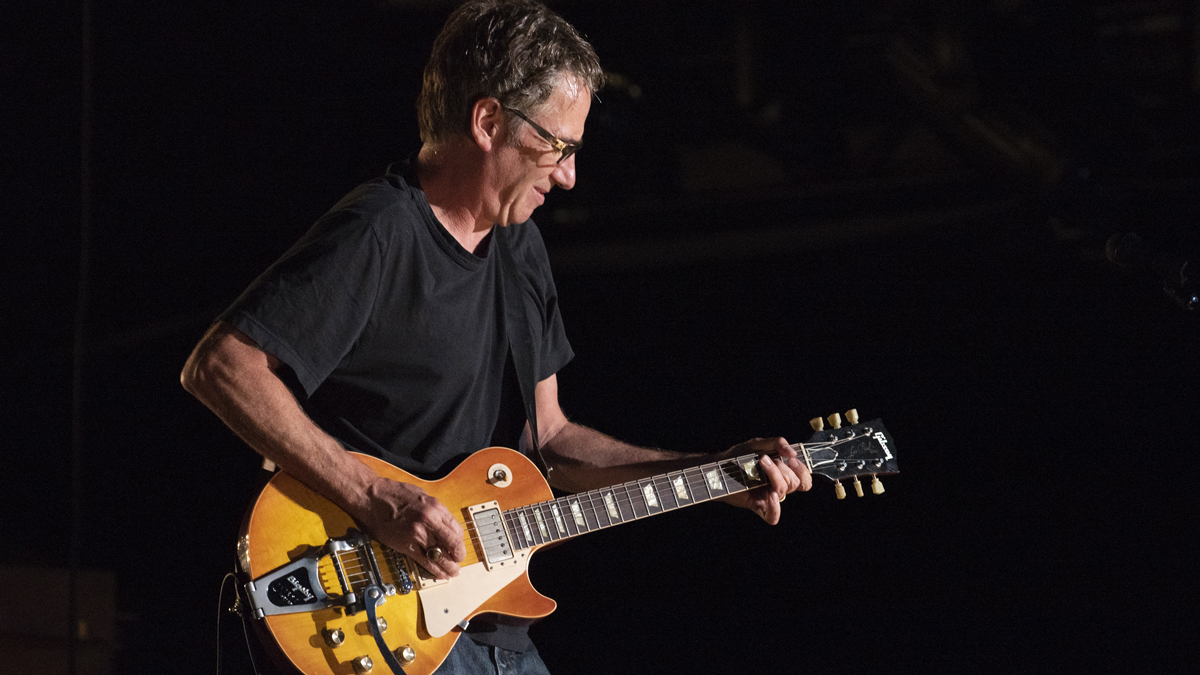

Stone Gossard and Mason Jennings on how breaking their guitar and songwriting habits led to Painted Shield’s electric debut

The veteran songwriters detail their fresh six-string approaches, lessons learned from Seattle greats, and why great songs come from removing as much as possible

In this line of work, it’s not often you find yourself speaking with a guitarist who really doesn’t want to talk about gear, but Stone Gossard’s devil-may-care attitude to recording sets him apart from most interviewees.

“Usually, for guitar sounds, I’m literally like, ‘What’s the amp that we got here? Is there a pedal? Plug it in. ‘OK, everything’s working,’” he laughs.

“I don’t really spend a lot of time thinking about it, because I’m so, I dunno… lazy! But also because sometimes the best stuff comes from whatever the circumstance is – just letting it be whatever it is.”

Rather than searching out the next big thing, Gossard relies solely on his ears and gut instinct to guide his tones and songwriting – but when it’s been his driving force for three-plus decades of irresistible riffs and grooves, who are we to argue?

Over a career spent negotiating the intertwining writing forces that fuel alt-rock juggernauts Pearl Jam, and working with some of rock’s greatest frontmen in Eddie Vedder, Chris Cornell, Andrew Wood and Shawn Smith, one thing Gossard knows about is collaboration.

It’s this adventurous creative spirit that found him knocking at the door of Mason Jennings, and led the pair to form electronic-rock crossover Painted Shield.

The group – which is completed by in-demand session drummer Matt Chamberlain and Seattle singer-songwriter Brittany Davis – release their debut, self-titled album this month, a brooding, electronica-infused marriage of Gossard’s syncopated hard-rock riffs and Jennings’ rich vocal range.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s an album that owes as much to ’70s glam as it does new wave, punk and trip-hop – and if it sounds like the work of a band several albums in to a career, that can be put down to the project’s long gestation period.

Formed six years ago at the recommendation of a trusted friend, Dan Fields – who happened to be Jennings’ manager at the time – Gossard cites the collaboration as “trusting a process that you don’t necessarily understand”.

“I write a lot of songs, so there’s only so much real estate on a Pearl Jam record for my indulgences,” he reasons. “Luckily, Mason is still appreciative of some of my songwriting efforts!”

That he certainly is. The pair’s early collaborations initially bore fruit in the form of a one-off single some years back, featuring the tracks Knife Fight and Caught in a Mess. But some of Gossard’s compositions date back much further – the basis of hard-rock jam Evil Winds was recorded 12 years ago, long before Jennings came into the picture.

All the music was coming to me from Stone, and then I would just crank it in my car and drive around, and just come up with stuff that way

Mason Jennings

Even considering the long gaps between Pearl Jam albums – with this year’s Gigaton arriving after a seven-year wait – this is the record that took longest to fully assemble for either artist. What’s more, the pair only physically crossed paths once during its creation, with the rest of the album recorded remotely.

In fact, the record didn’t near completion until Chamberlain – who himself had a brief stint with Pearl Jam in the early ’90s – and Davis took a bigger role in the process, fleshing out existing arrangements and bringing entirely new soundscapes to the table.

When it came to guitar playing, however, Jennings is quick to clarify that his contributions were vocal only.

“I got demoted. I got my guitar taken away,” he laughs. “I just sang, so it was cool for me. All the music was coming to me from Stone – and he had stuff he’d done with Matt Chamberlain prior – and then I would just crank it in my car and drive around, and just come up with stuff that way. It was super-cool.”

Jennings would be listening to demos assembled by Gossard and Chamberlain for long periods of time before writing – sometimes he would pen his contributions years after hearing the initial track.

Shaking up the songwriting process and breaking habits was key to Painted Shield’s work ethic, according to Gossard, who saw his role as a “cheerleader” as much as a songwriter, encouraging the new contributions coming his way from Chamberlain and Davis.

Gossard was also rooting for mixer John Congleton – whose keen ear has shaped the off-the-wall guitar sounds of records from St. Vincent, Baroness, Explosions in the Sky and countless other sonically bold outfits over the years.

It was his hand that tore the entire album apart once it had been recorded, and lent it its fresh, progressive production.

“Congleton took a lot of the main guitar riffs and would pull them. Sometimes this harmonic soloing part would be the only thing in,” Jennings enthuses. “Stone was so brave to go, ‘OK, John, let’s take out my actual riff, and let this little thing come all the way to the front.’ And it turned out cool. I was blown away.”

“When you make records, you pile too much stuff on,” Gossard concurs. “And to have somebody re-prioritize, and really listen with fresh ears, where you can hear where something gets redundant, or hear where a song needs a shift emotionally, it can be a really helpful process. Particularly in a situation like this, where we don’t have a history – there’s no expectation other than, ‘I wonder what it is?’”

There’s lots of direct guitars – I love that, where you plug directly into the [mixing] board, but you just run it through a bunch of preamps, so it breaks up in a way that feels very present, very close

Stone Gossard

It wasn’t just Congleton who lent the album its distinctive guitar sounds; despite not being a gearhead by any stretch of the imagination, Gossard has always been keen to push the envelope.

“I love freaky guitar tones, and I’m always trying to do something [different],” he says. “We were always throwing on fuzzboxes, and these days, in terms of mixing, everybody’s always running guitars through another filter, or another delay…

“There’s lots of direct guitars – I love that, where you plug directly into the [mixing] board, but you just run it through a bunch of preamps, so it breaks up, but it breaks up in a way that feels very present, very close.”

While he admits he has “no idea” what amps made the cut on the record – “vintage Fender amps, maybe it’s a Vox, or maybe it’s a Marshall” – the key guitars were clearer in his memory.

“I played my Les Pauls with Bigsbys a lot,” he recalls. “I mean, I like a Bigsby just for a little movement sometimes. I have a Strat with a Bigsby now. [laughs] Totally sacrilegious!”

As that burgeoning Bigsby obsession testifies, some habits die hard – and in his new cheerleader role, Gossard couldn’t resist bringing a few friends along for the ride.

When GW compliments the lead playing on the track’s riff-rock lynchpin Evil Winds, he laughs, “You know who that is? That’s Mike McCready! Yep, wherever I go, Mike McCready lurks in the background.

“I feel lucky – he came in and blasted a solo, and didn’t even think about it. He also played the solo on On the Level. We had a lot of guests on the record, so if you hear something and you think suddenly I’ve improved as a guitar player, you might be disappointed.

“Jeff Fielder, who’s a fantastic Seattle guitar player who’s played with Mark Lanegan for ages, is also one of my go-to guys. He plays all the sitar parts on Knife Fight, à la Steely Dan.”

Yet for all the guests, all the solos, all the layers, the key learning Gossard has taken from the process is removing all non-essential elements – a realization that’s slowly been dawning throughout his time with Pearl Jam.

In fact, when it comes to riffs, leaving that space for grooves to ferment and grow has become something of a signature move for the guitarist.

“Subtraction is my method at this point,” he says. “It’s: what’s your idea, and then how much can you take away where your idea is still percolating in there, but you create more space for other melodic energy and vocals.

“People like the Edge understood that from the get-go, in terms of how space is this instrument that has to be used effectively. But it took me a long time, because I’ve just been in bands where everyone’s playing all the time. I mean, that can be cool, too – the cacophony, the onslaught, that’s great – but in this particular case, I think space is great.”

The big thing I learned is how different acoustic and electric are to play. I don’t think they should both be called guitar, even!

Mason Jennings

The subject of space leads Gossard and Jennings to talk amongst themselves, effusively praising the new demos they’re already working up for the next Painted Shield record.

Their excitement is palpable. In fact, it seems fair to say that this looks to be a longterm endeavor.

“We’ve got Painted Shield stuff brewing right now,” Gossard enthuses. “It’s so easy to do, because we just send songs back to each other, so there’s no reason why we couldn’t. Unless we have major disagreements about [adopts snooty tone] art!”

That seems unlikely. Even on the subject of the guitar lessons the pair have learned over the years, Jennings strikes a similar tone to Gossard, noting how a lighter touch is what makes electric players great, and acoustic – his usual go-to – needs a very different approach.

“The big thing I learned is how different acoustic and electric are to play,” Jennings says. “I don’t think they should both be called guitar, even! An acoustic guitar is so physical – you lean in, and it has a completely different response. I spent so much time playing acoustic, and it’s similar to drums.

“And then electric, I watch these interviews on YouTube with people that I really love, like Mark Speer from Khruangbin, and his gear setup, and the way he’s conceptualizing sustain and his pedals. It’s almost like he’s a car mechanic, a gearhead – he understands electronics, how to play something light and have it sound huge.”

An awareness of texture and tone shines throughout the Painted Shield, even during forays into previously uncharted territory for its guitarists, such as the industrial synths that drive Chamberlain-penned curveball I Am Your Country.

While the sonic landscape looks different, Painted Shield highlights that unifying thread across Gossard’s career: collaboration. Although, by his own admission, he never sought out to work with some of the greatest musicians in rock… it just happened.

“They’re just people that you see in your neighborhood, or you meet through friends,” he recalls. “And it’s just shocking to me that I got to play with Andy Wood and Shawn Smith and Chris Cornell. I guess the rock and roll aspect of it is wherever you are, and if you’re trying to make a band or trying to discover something, most likely it’s probably right in front of you.

“All those guys were big musical sharers. Eddie is one of the foundational artistic people in my life in regards to how much I care about art and how important it is and what your process is, and people’s eclectic natures, and embracing those. I’m the luckiest guy in rock!”

As for whether he’s picked up any lessons from the many guitar players he’s worked with over the years, Gossard doesn’t name any specific techniques; rather, it’s their attitude towards the instrument that has shaped his own approach.

“With Chris Cornell, he would get into great detail and has tons of harmonic knowledge,” he explains. “But I think he would have said he didn’t have a schooled background in terms of why the harmony he was putting down made sense.

“It’s important to study, but also learning just by trusting your ear and trusting your natural instincts about how to make an instrument exciting can be a really powerful weapon in your arsenal.

I have a talent, but it’s really the same thing that I’ve been doing since I was 16 years old, which is just stumbling on guitar

Stone Gossard

“The guitar needs to be treated like the sandbox sometimes, where it could be anything: you could bang on it with a stick, make up your own tunings. Finding different ways to make it simple, so that when you pick it up you can do a couple of things and all of a sudden it sounds good. I just think there’s a world of opportunity for amateur guitar players – you don’t have to be great. I’m proof of that!”

Gossard’s modesty overlooks the fact that he remains one of rock’s most respected rhythm players. When both GW and Jennings pipe up to remind him that, really, he’s quite good at the instrument, Gossard outlines a simple philosophy that’s guided his musical journey, from the moment he started playing guitar through every record he’s made to date, and every record he’ll make in the future.

“I have a talent, but it’s really the same thing that I’ve been doing since I was 16 years old, which is just stumbling on guitar,” he laughs.

“Literally just stumbling around until I hear two notes that make me go, ‘Oh, that’s cool – going between that note and that chord to this note all of a sudden,’ so that’s my change.

“I’m just gonna hang on to that and see what happens, and I’ll just keep making more stumbles, and then you sort of have a sonic sound that doesn’t sound like anything else… It sounds good to your ear; it sounds like you.”

- Painted Shield’s debut album is out on November 27 via Loosegroove Records, and available to preorder now.

Mike is Editor-in-Chief of GuitarWorld.com, in addition to being an offset fiend and recovering pedal addict. He has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University, and over a decade's experience writing and editing for guitar publications including MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitarist, as well as 20 years of recording and live experience in original and function bands. During his career, he has interviewed the likes of John Frusciante, Chris Cornell, Tom Morello, Matt Bellamy, Kirk Hammett, Jerry Cantrell, Joe Satriani, Tom DeLonge, Ed O'Brien, Polyphia, Tosin Abasi, Yvette Young and many more. In his free time, you'll find him making progressive instrumental rock under the nom de plume Maebe.

“A virtuoso beyond virtuosos”: Matteo Mancuso has become one of the hottest guitar talents on the planet – now he’s finally announced his first headline US tour

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83