Stevie Ray Vaughan: Weather Report

Originally published in Guitar World, July 2010

With a deluxe reissue of Couldn’t Stand the Weather in the forecast, Stevie Ray Vaughan’s bandmates recall the making of a modern blues rock classic.

In March 15, 1984, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble took the stage in Honolulu, Hawaii, for a special show. Their audience consisted solely of CBS Records employees, including the publicity, radio promotion and sales reps at the Epic label, who were preparing to work the band’s just-completed second album, Couldn’t Stand the Weather. The performance was meant to be the highlight of CBS’ annual convention for its music division. To Stevie Ray and his bandmates, the very fact that they were in Hawaii felt like a vote of confidence at a critical time in their career.

“CBS had lots of acts,” Double Trouble’s drummer Chris Layton says today, “and they could have flown any of them out to Hawaii, but they picked us. When we first heard that we were going to the convention, we thought, Great, this means they’re serious about us.” In an era when synth-pop dominated the musical landscape, Vaughan’s corporate backers were betting that what the world really needed was some white-hot blues guitar.

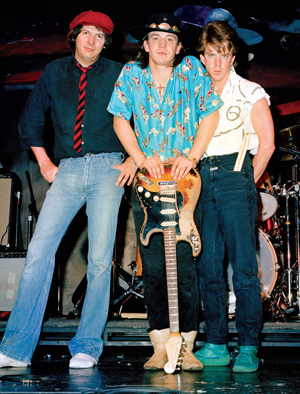

Vaughan and company responded to the honor with a spirited set, interspersing impressive new compositions like “Scuttle Buttin’,” “Stang’s Swang” and “Couldn’t Stand the Weather” with favorites from Texas Flood, their debut album, released the previous year. The show reached its pinnacle with a blistering take on Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).” Outfitted in a light-blue kimono and his customary black bolero hat, Vaughan made his favorite “Number One” Strat howl with a bottomless passion that simultaneously evoked Hendrix and confirmed Vaughan as a master in his own right. (The concert was recorded and will soon be available for the first time as part of Sony Legacy’s upcoming deluxe reissue of Couldn’t Stand the Weather.)

The record company employees applauded and cheered. The bet they’d made about Vaughan’s continued commercial potential would pay off soon enough: Couldn’t Stand the Weather sold 250,000 copies in its first 21 days of release. It eventually reached Number 31 on the Billboard album chart and achieved double-Platinum sales. Undoubtedly, SRV’s appearance at the convention helped light a fire under the Epic team, but it didn’t hurt that the record was a winner.

Double Trouble bassist Tommy Shannon doesn’t remember much about the Honolulu performance itself, but he says of the trip overall, “We had a lot of fun.” Layton adds a few more specifics: “It was a world party. Unlike most gigs, we got to hang out there for three days and meet people. It was sunburns, margaritas, Mai Tais, piña coladas and cigars. I never saw anybody without a drink in their hand.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Before long, the band’s hard-partying style would cause serious problems, but as the winter of 1984 turned to spring, everything was still—just barely—under control. The Texas trio could revel in its good fortune and in the successful completion of an album that many still regard as the group’s finest.

The recording sessions for Couldn’t Stand the Weather were a drastically different experience from the three-day weekend at Jackson Browne’s L.A. studio that had produced Texas Flood. As Shannon told Guitar World in February 2004, the latter album “wasn’t even meant to be a record”—it had been intended purely as a demo to shop around to labels—while its follow-up “was all about being a record, ceremoniously.”

By the end of 1983, Texas Flood had gone Gold, selling more than 500,000 copies in the U.S. Having already proved their worth to CBS, Vaughan and his bandmates were now in a position to raise the bar. The new album would be recorded over six weeks at the famed Record Plant studios in New York, and the man behind the glass in the control room would be none other than John Hammond, the legendary A&R man who had discovered Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, and who had been instrumental in signing Vaughan to Epic.

However, before Stevie, Tommy and Chris could make the trip to New York, they had to figure out what they were going to record there. They’d been on the road nonstop since Texas Flood’s release and they had no new material prepared. So Vaughan booked a three-week stint at an Austin rehearsal hall for preproduction work. It was rough going at times, because the band wasn’t entirely sure of what musical direction to pursue. According to engineer Richard Mullen, Vaughan’s longtime sonic right-hand man, “There were probably 5,000 different song lists. The joke of the sessions was that every time Stevie went off to do a line [of cocaine], he’d come back with a different list.”

Among the pieces that Vaughan and the band finalized during this time were “Scuttle Buttin’,” “Stang’s Swang,” “Honey Bee” and “Couldn’t Stand the Weather,” songs that moved the band well past basic blues into jazz, soul and rock. The now-classic unison bass/guitar riff that opens “Couldn’t Stand the Weather” was originally Shannon’s idea, but he later explained that his version of the riff “was phrased differently. I had the first note falling on ‘two’ instead of ‘one’—it was more like a horn line—and Stevie suggested changing that first note to the ‘one.’ ” As for the astonishing instrumental “Scuttle Buttin’,” it was a tribute to the roughhewn style of pioneering blues-rock guitarist Lonnie Mack, closely based on the tune of Mack’s “Chicken Feed.”

One more important decision was made while in Austin: the band members agreed that when they got to New York, they would commit their version of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” to tape. They’d been playing it live regularly, but Vaughan had been reluctant to record it. “I really had to talk Stevie into doing that track,” Shannon says, “because he was afraid of what the ‘blues purists’ might have to say about it. I said, ‘Hey, there’s nothing wrong with stepping over the line.’ ” Vaughan’s willingness to consider recording a straight-out rock song was a clear sign that Couldn’t Stand the Weather would not be a repeat of Texas Flood, and the decision to cut it was an important one for the group.

“That track was responsible for bridging the gap between blues and a totally new kind of music,” Layton says. “For us, it was like we were breaking out of jail. ‘Voodoo Child’ turned out to be our point of departure into the future.”

In the new year, the action shifted to New York. Stevie, Tommy and Chris checked into the Mayflower Hotel on Central Park West and proceeded to live it up just about every waking second that they weren’t playing. They quickly developed tight relationships with several local drug dealers. “We were high on how cool it was to be recording in New York with the record company’s blessing,” Layton remembered later. “But we were real high, too. There were two distinctly different highs going on.”

At the Record Plant, the music poured out with ease. Toward the start of the first day of recording, Richard Mullen asked the trio to play something so he could tweak the instrument sounds. With hardly a word, they struck up a version of Bob Geddins’ slow blues “Tin Pan Alley.” As he did for most of the sessions, Vaughan stood near Layton’s drums and played without headphones, focusing on the band’s live sound. (The lack of headphones also freed him to move about the studio the same way he did onstage. “He’d dance around, slidin’ across the room on his toes, stuff like that,” Mullen recalled.)

Vaughan’s solo on “Tin Pan Alley” was cool on top but simmering with emotion underneath, punctuated by cleanly picked bursts of notes that rippled across Shannon and Layton’s groove like waves in a pool of wind-blown water. When the song was finished, John Hammond spoke from the control room through the talkback mic. “You’ll never get it better than that,” he said. His statement turned out to be correct; the very first take of the very first song played at the sessions ended up going on the album.

Working in the studio with Hammond was a treat, but it wasn’t quite what the band had expected. “He’d come in every day with the New York Times, and he’d just sit there and read the paper while we were playing,” Shannon recalls. “We started thinking, What’s he doing in there? Is he even listening? But then at the end of the song he’d go, ‘We should try that again,’ or ‘Let’s move on, that’s good.’ And he was always right.”

Behind his newspaper, Hammond was also paying attention to the band’s rampant cocaine use, which they did a poor job of hiding. One day, he announced out of the blue that Gene Krupa had been his favorite drummer to record back in the swing heyday of the Thirties, but that Krupa’s timing deteriorated whenever he smoked pot. “Ever since then,” Hammond concluded, “I don’t allow drugs in my sessions.” From that point on, Layton said, “We got the message, even though all we did was try to hide it from him a little better.”

Vaughan had less consideration for other representatives of the label. “The A&R and marketing people wanted to come in for a listening party midstream and evaluate the recording,” Layton told Guitar World in February 2004. “Stevie said to them, ‘You think we did pretty good on the first one, don’t you?’ And they said, ‘Oh, it’s wonderful.’ So he said, ‘Then we don’t need your help on the second one.’ ”

One Epic employee didn’t get the hint. He snuck into the studio one night after the band had departed, and left with an early version of “Look at Little Sister” in rough-mix form. The next day, Layton reported, “Stevie called him up and ripped him a new asshole: ‘Don’t you ever fuckin’ come in and take my music. I don’t give a fuck if you’re with the record company!’ ” Vaughan pointedly left “Look at Little Sister” off the final album. It finally turned up on 1985’s Soul to Soul in a re-recorded version.

Vaughan’s annoyance is understandable, but it’s easy to see why Epic wanted assurance that it would get a return on its substantial investment. Even at the time, Layton says, “I did begin to think about all the money that was being spent for limousines and expensive hotel bills. I could hear [manager] Chesley [Millikin] saying, ‘We’ve already spent $80,000 on this record!’ and we were just about done with the basics.”

Luckily, once the basics were done, there wasn’t much left to do. Most of the album tracks were basically cut live in single takes, including the eight-minute rip through “Voodoo Child,” which Vaughan played on his trusty Number One, plugged into his new 150-watt Dumble Steel String Singer, connected to a 4x12 Dumble cabinet and two Fender Vibroverbs and cranked to an earthshaking level. Among the few nonvocal overdubs was a second guitar track for “Stang’s Swang,” for which Vaughan switched to a Gibson Johnny Smith and a Roland JC-120 amp.

Serendipity continued to rule right up to the end of the sessions. When Vaughan’s brother Jimmie dropped by to play a rhythm guitar part on “Couldn’t Stand the Weather,” he suggested putting in a longer pause between statements of the opening riff. Stevie liked the idea. While the tape was rolling, he simply put his finger to his lips after they’d played the riff for the third time, waited two-and-a-half extra beats, and then cued the band to come back in. This take—cut with no prior rehearsal of the break—was the keeper. “It took us a little by surprise,” Layton says, “but we were so tight at that time that he could have made [the pause] five and six one-hundredths of a beat and we’d have been right there.”

The session that produced “Cold Shot” also took Layton by surprise. Vaughan woke the drummer up from a studio nap at 4 A.M. to record the song. The tune had been written by W.C. Clark and Mike Kindred, two of Vaughan’s former bandmates. “We’d worked on it in Austin,” Layton remembers, “but Stevie hadn’t been happy with the arrangement, and he hadn’t said anything more about recording it until that night. That was the first time we’d ever played that particular arrangement of the song from beginning to end. We cut it without a vocal—Stevie overdubbed that later—and we did it in one take, and that was the track.” In the end, “Cold Shot” and its slinky late-night rhythm would play a crucial role in introducing Vaughan to a broader audience. The song’s video, in which Vaughan gets beaten up by a succession of girlfriends jealous over his attachment to his ax, became a regular on MTV.

Enough extra material was recorded at the Power Station to fill another disc; 10 additional songs from the Weather sessions (not counting alternate takes of songs that made it on the original album) have since appeared on later CD reissues and on the posthumous album The Sky Is Crying. The fact that people can now hear these tracks as well pleases Shannon. He says, “Obviously, we picked the songs that we thought were best for the album, but nothing we did at those sessions was bad. As time goes on, you tend to listen to things more objectively, but I still hear that stuff and say, ‘Damn, that was good.’ Stevie’s playing constantly surprises me—he was always pulling something new out of the hat.”

In fact, Layton confesses that he likes Couldn’t Stand the Weather much more now than he did in 1984. “I can appreciate the good parts more,” he says. “I do wonder what the music would have been like without the excessive partying. The real tragedy of Stevie’s passing was that we’d finally overcome those demons. But the fact is we did the best we could do, and the best we could do was pretty good.”