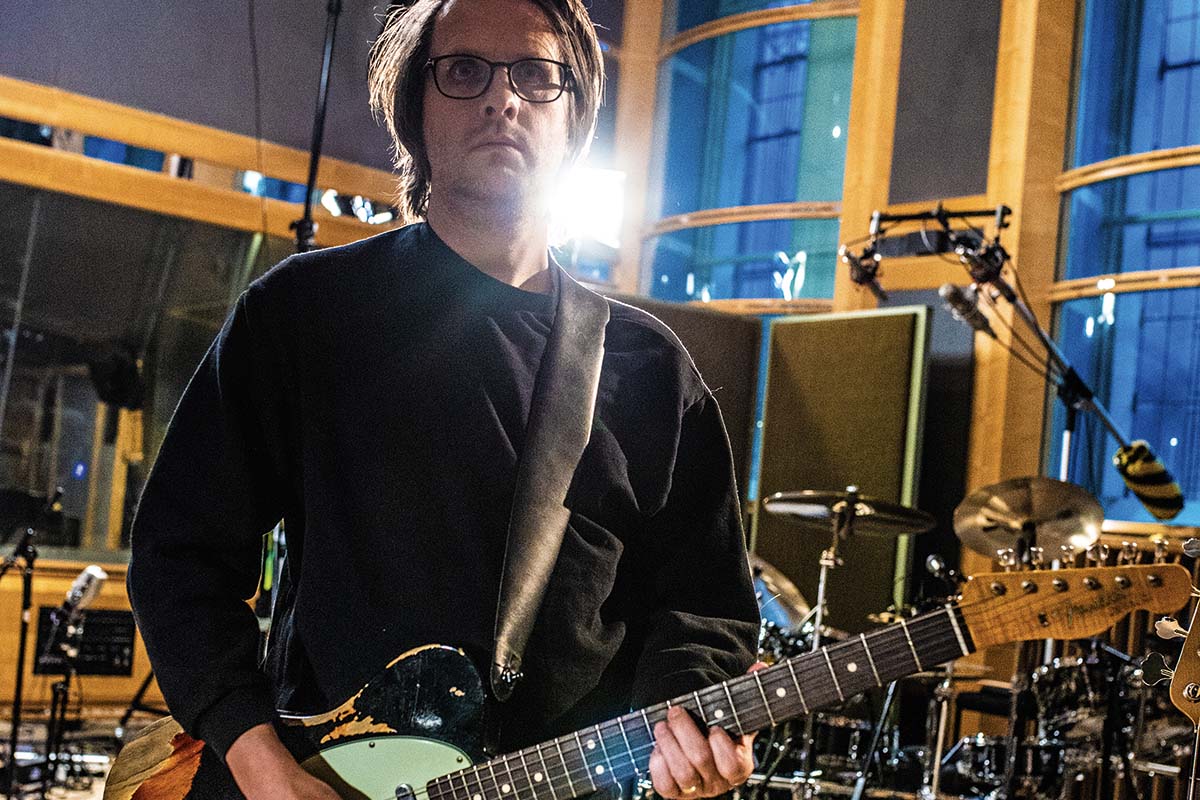

Steven Wilson on Porcupine Tree's triumphant return and his love of “guitar players that can play one note and break your heart”

Porcupine Tree’s comeback album, Closure/Continuation, is a prog masterclass, but Wilson insists he is no virtuoso. He does, however, know how to to take happy chords over to the dark side...

After playing the biggest gig of their career, most bands would carry the momentum forward and set their sights on challenges new. Porcupine Tree, however, are not like most bands. After headlining at the Royal Albert Hall in October 2010, their leader Steven Wilson, guitarist and vocalist, decided it was time for the group to take a break.

12 years on, with Wilson having built a successful solo career that has commercially outperformed the progressive rock band that first got him noticed, he has reunited Porcupine Tree as a trio, with drummer Gavin Harrison and keyboard player Richard Barbieri.

Their new album, playfully titled Closure/Continuation, revisits some of the avant-garde brilliance that built them a cult following, while also treading new atmospheric ground.

Wilson is now widely regarded as the most prominent and prolific figure in modern progressive music. And yet, for all the complexity and odd-time riffs in Porcupine Tree’s music, he has a simple approach to guitar. “I don’t have the technique,” he admits. “But then again, I don’t really want to play fast anyway.”

Let’s start with why Porcupine Tree split up in 2010...

“I felt like we’d achieved everything we could achieve within the confines of this musical vocabulary and style we had spent years creating and developing. We got to [2009 album] The Incident and I think for the first time it felt like we were no longer progressing or taking that sound forward. It was that dreaded expression: ‘more of the same’. For me, that was a massive red flag. So we went off in our own ways.”

But it only took a couple of years for you to haphazardly start working on new music together?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Yeah. In 2012, Gavin and I started meeting up for a coffee. I just picked up a bass guitar sitting in the corner of the studio and we started to write grooves and polyrhythms. And that is the bedrock of this new album. When you hear the opening track Harridan, which has this five-count bass and drum groove, that was one of the early things that came out of those jams.

“Other ideas were thrown on top, but a lot of it was written on bass and drums. In the meantime, Gavin was busy playing with King Crimson, I was busy with solo records and Richard was too. So for us it was a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’, although if you told me in 2012 if it would be another 10 years, I would have been surprised by that.

“As it turns out, it’s been a very slow process. Without the lockdown we probably wouldn’t have finished it, because the time off from various tours being cancelled gave us an opportunity to knuckle down.”

How do you see your solo career and Porcupine Tree co-existing?

“I guess the reason why the timing feels perfect right now is because my solo music has diverted a long way away from the Porcupine Tree sound. And there have been moments in the last 10 years where that wasn’t the case. [2015 album] Hand. Cannot. Erase. was quite close musically, I think. Some fans even felt it could have been a new Porcupine Tree record. In recent years, however, my solo music has come a long way from that.”

On the band’s new album, the opening riff to Rats Return feels like one of the heaviest things you’ve ever written, especially with the Opeth-style tritone stabs.

“What’s interesting about that riff is that it’s almost the answer to an equation Gavin set me. The rhythm came before the riff. Gavin came up with the pattern with all those stabs and I had to sit there and figure out what I could do to that.

“It was like finding the answer to a mathematical problem! That’s one of the beautiful things about how this album developed. It was very collaborative. Gavin never sets you an easy task. Harridan is in five, Herd Culling is in 11 and Rats Return is another odd-time one. When he played it to me, I thought, ‘What an interesting rhythm… but what the fuck is it?!’

“The riff came out of that. It never would have existed without Gavin’s rhythm. I’ve always liked dark riffs and evil tritone things, especially given how I grew up listening to King Crimson and Black Sabbath. Those discords have always appealed to me, there’s something beautiful about an ugly chord, so here we are!

“Someone told me the other day that they loved the fact we’d gone back to drop-D riffs and I said, ‘No, it’s in regular E!’ There’s not much gain on that riff, it’s actually quite clean. And it’s my Telecaster doing that, they can make things sound gnarly and heavy without needing to put a lot of drive on. So the tone isn’t really a metal tone at all.”

The major 3rd and flat 7th gives it a Phrygian Dominant feel, which is probably where that metallic flavour comes from.

“I don’t know much music theory, so I pretend I don’t give a shit about it! But I guess I do, deep down. This one came out of my love for discordant metal riffs, and it’s worth remembering Magma and Mahavishnu Orchestra were exploring those harmonies in the early ’70s.

“Then you had Swans in the ’80s. I’ve always loved that sound. You can go back to 20th century classical music and hear it in the music of Scelsi, Xenakis or Stockhausen. I like those ugly harmonies and tritones.”

You can make a major seven sound really evil depending on how you use it and I love that – taking something happy to the dark side

Of The New Day carries some major 7th chords that feel far from happy...

“Right. Major sevens are among the friendliest chords out there – they tend to sound very nice and conjure up summer days – but there’s actually a way to make them sound really evil! So I might take a minor idea and throw them in.

“For the riff in Of The New Day, I’m changing from a straight A power chord on the fifth fret to a Bbmaj7 by fretting the sixth fret on the sixth string, the fifth fret on the fifth and the seventh fret on the fourth.

“And I do a similar thing near the end of that snakey riff in Harridan, using that exact same chord on the fourth, third and second frets. You can make a major seven sound really evil depending on how you use it and I love that – taking something happy to the dark side.”

What advice can you offer those hoping to come up with their own odd-time riffs?

“Work with an interesting drummer, it’s as simple as that. Gavin will never give me a straight rhythm. Woe betide he ever works in 4/4! So you’ll get something that will make you think and stretch you. Herd Culling was the last song written for the record. I felt like we needed one more so I asked him to send over some patterns, and they were in 11.

“Again, it was like a mathematical equation. What riff would work well here? Working with an interesting drummer will force you to come up with polyrhythmic and odd-time guitar parts. Gavin’s the king of unusual rhythms that can take a track in different directions.

“Richard tears his hair out because he’s not naturally inclined to work that way. He’s always saying, ‘Fuck sake, can we not just work in 4 this time?’ I’m in the middle. I love the simplicity of Richard’s sound design. It’s the non-musician approach of sculpting noise. And Gavin is the opposite, he’s a total pro musician who wants to say complicated things that are easy on the ear.

“Of the New Day has 50 time changes in it and yet superficially it just sounds like a straight country ballad. So if you want to look below the surface, there is complexity there. If you don’t, and just want to enjoy the music, it works on that level too. We’re not hitting you on the head saying ‘Listen to how clever we are!’ And there’s a lot of that around these days.

“Most people listen to Money by Pink Floyd and enjoy it as a great piece of pop without engaging with the fact it’s in seven. Pyramid Song by Radiohead is another one – very complex rhythmically but most people don’t need to look at it like that. It’s just a beautiful song.”

Your solo in Dignity is very understated and lyrical, in the style of David Gilmour.

“I’ve always loved guitar players that can play one note and break your heart rather than the ones who play 20 notes that go in one ear and out the other. I would love to be able to play guitar like that just to have the technique, but I don’t have the inclination.

“It’s a bit like Picasso – he was an incredible technician and painter but chose to create in a primitive style. I love the idea of playing just one note and breaking someone’s heart that way. Mikael [Åkerfeldt] from Opeth is one of my favourites in that regard. He has Fredrik [Åkesson] who plays all the clever stuff which is amazing, but it’s Mikael’s solos that really speak to me. He has that ‘lonely Swede lost in a forest’ quality!”

Who else do you admire on that level?

“You hear it in Peter Green’s early work with Fleetwood Mac, you hear it in David Gilmour and bands like Talk Talk – there’s a solo Mark Hollis played on the album Laughing Stock where it’s just one note played for a minute! Literally nothing more, but it’s so good. I also love Pete Shelley’s solo on Boredom by Buzzcocks for similar reasons. Less is more, with me. I’m more into the feeling and sound, rather than all the notes.”

Purists will be horrified but I used the direct out on my little Hughes & Kettner TubeMeister 5 a lot! It sounds killer!

You’ve been a Telecaster enthusiast since 2017’s To The Bone. Given that some of these songs predate that album, are we hearing your PRS Goldtop on the album too?

“Yeah! We started making this album before that love affair began, so a lot of the early sessions that we kept were done with my old Goldtop. But all the stuff that came later on was done with the Tele, which is what I’ll be using live for the new songs.

“There’s one part in Harridan where I switch to a baritone to play the low riff in B, but otherwise it will be mostly Tele. I’ve got an endorsement with Takamine so I use their acoustics a lot but on this record it was mainly my PRS Angelus. On Chimera’s Wreck I was using my Ovation strung Nashville-style to get a very crystalline, musical box kind of tone.”

There are some really interesting modulations on the album too – particularly in terms of tremolo and vibrato. What were you using?

“The tremolo is the Moog MF Trem. I use vibrato a lot, and my favourite one is made by Diamond. And I’ve also got the Option 5 Rotary pedal, so those are my main modulation pedals.

“Then there’s the two Strymons, the Timeline and the Big Sky. I have two POGs on the ’board, one tuned an octave up and the other an octave down, which got used once or twice on the record.

“Purists will be horrified but I used the direct out on my little Hughes & Kettner TubeMeister 5 a lot! It sounds killer! All the sounds on Herd Culling were through that. And I used my Supro combo with a 57 on it for clean tones, like that lead on Dignity. I still have my Bad Cats too, of course, just for the heavier tones.”

You certainly have a knack for using multiple effects in tandem to conjure up abstract noises.

“That all comes from shoegaze music. Stuff like My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive, who have these impressionistic tones with a big cloud of echo and reverb, and then strum chords through them. The guitars become more of a texture, like a choral sort of sound.

“Robin Guthrie from Cocteau Twins would play just one note that would set off a whole chain of effects: delays, choruses, flangers and harmonisers. It’s like the smallest physical gesture creating this heavenly cathedral of sound. I think the black metal guys totally got that too.

“It’s the total opposite of the shredder thing, which can have a very clean and uninteresting tone to allow you to hear all the notes. I guess I’m more into abstract ideas where you can’t hear all the notes!”

- Closure / Continuation is out now via MRI.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo