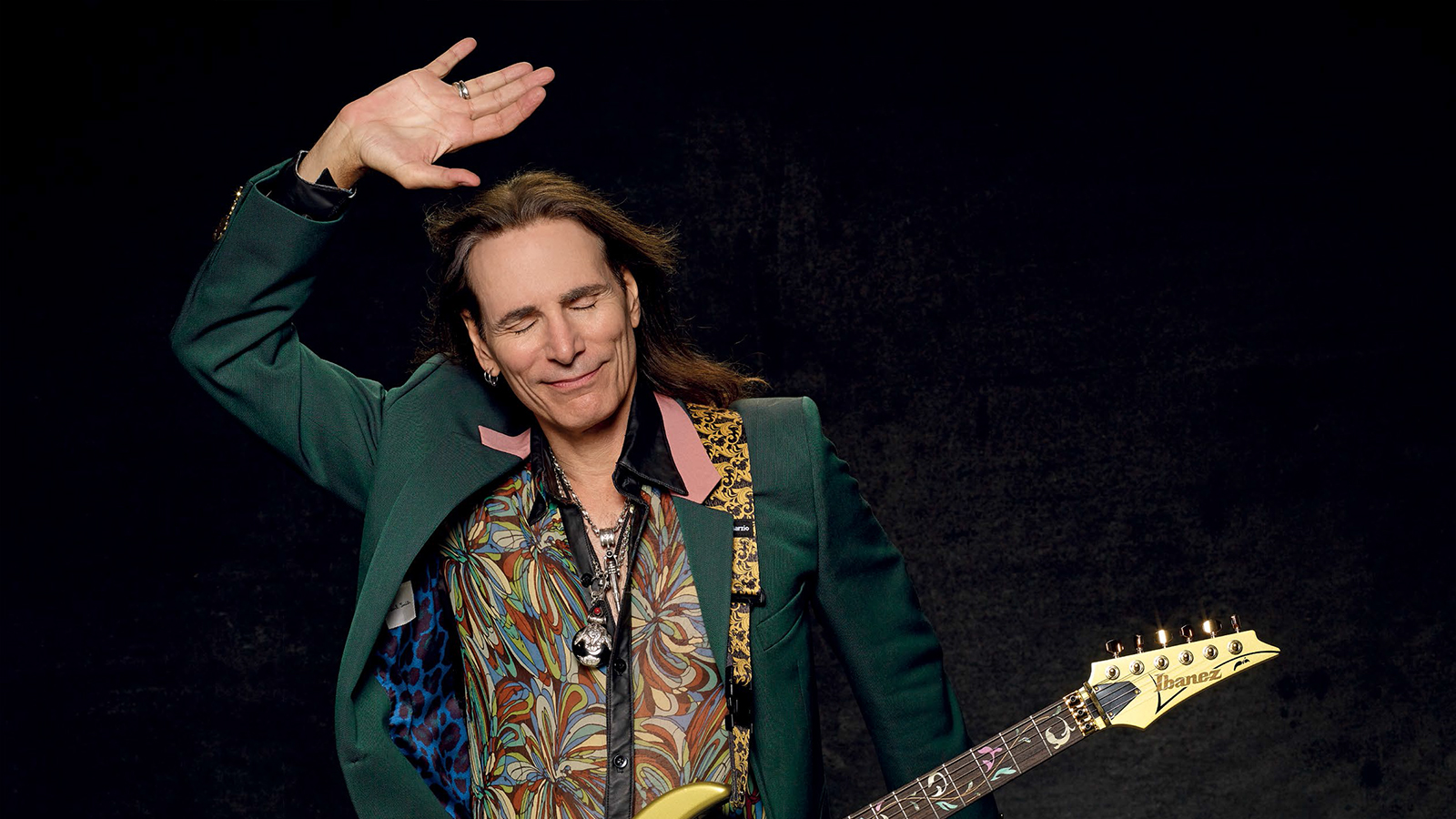

Steve Vai: "When I was a kid playing guitar too loud, the neighbors would complain... and my father would tell them to shut the f**k up"

Best of 2020: By the standards to which we usually tend to hold rock stars, Steve Vai doesn’t quite fit: He’s never been arrested. He’s never punched anybody out. He doesn’t have a drug or alcohol problem. He’s never wrecked a hotel room or driven a car into a swimming pool. He doesn’t engage in Twitter wars with fellow musicians (in fact, he routinely offers kind words for anybody he’s ever played with, and those compliments are summarily returned).

He’s never released a sex tape, nor does he have a string of ex-wives dishing dirt on him. Truth is, his home life could be described as a model of everyday suburban stability: He’s been married to the same woman, Pia, for 31 years, and the couple have two great kids, Fire and Julian Angel.

So how is it, then, that Steve Vai is a rock star? “Well, I would hope the answer lies in the music itself,” he replies. “You can make the music without all that other stuff. See, I fell in love with rock ‘n’ roll as a kid, and it’s stayed with me ever since. The energy of it, the sound, the melodies, the freedom - it got in my blood.

"I knew at a very young age that I wanted to play this kind of music - well, of course, in my own way - and that’s really been what’s guided me throughout my life. When I think about people I know or have met who are quote-unquote 'rock stars,’ their temperaments vary greatly - they’re everything from really depressed people to very centered and happy people.

"And it’s not uncommon to dabble in various vices - drugs, sex, money. But for me, those things never really had much of an attraction. There was always something in me that never let me take things too far.”

For Vai, the secret to avoiding some of the pitfalls that have crippled a few of his contemporaries lies in a carefully considered choice between impulses. “It really comes down to two options,” he says. “There are bad ideas, which are the dangerous indulgences - having a drug monkey on your back or complicating your life with affairs - and all those things can destroy your creativity.

"I was always drawn to the power of a really good idea, and that’s musical creativity. That’s always the thing that excited me the most. So to pursue that really good idea, I find it’s better to have a comfortable, simpler life.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Steve Vai is certainly at an interesting point in his life and career. At 59, he’s surely too young to be considered an elder-statesman guitarist, but 60 is in his sights, and he admits it feels like it will be something of a milestone. “At this point in my life, when looking back at all that’s been accomplished, I feel completely fulfilled and grateful.

"In fact, I never expected that I would accomplish as much as I have, and although I still love the creative process more than ever, and I still have a great many engaging projects ahead of me, if it all ended today I would still feel complete.

"It’s a great head space to live in, and all it requires is a little focused appreciation of all that you have now and all the creative contributions you’ve made. If you can do that, I think it’s impossible for anyone not to be making creative contributions.”

The guitar always felt like magic to me - it was the gateway to my imagination

Hearing Vai speak in this way, it’s so easy to feel swept away by such a philosophy, but when pressed, the guitarist does allow that his perspective “is very much a 59-year-old Steve Vai speaking.” He reveals that he has felt trapped by intense bouts of depression at various periods in his life, plagued by periods of insecurity and notions that his work was never fully appreciated.

“It’s a form of insanity, though, isn’t it?” he says. “It’s very painful psychologically, and it’s all brought on by fantasy ego beliefs. You think you haven’t accomplished anything, that you don’t have enough fame or money, or that you haven’t arrived. But after a while, you learn to let go of all that, because it’s hell.”

One way in which Vai has learned to let go is through spiritual growth; each day he sets aside time to reflect and, as he puts it, “search for the peace within myself.” And he inevitably turns to the guitar. “Even through difficult periods, it’s been my happy place,” he says. “The guitar always felt like magic to me - it was the gateway to my imagination.

"How a person expresses their imagination is up to them, but for me it’s been in the form of little black dots and the guitar. So it’s always been my friend.” He pauses. “Of course, there’s the flipside to that: I can get very critical about myself, and then the guitar becomes unfriendly.” So what does he do in those instances?

“I just learned that it’s got nothing to do with the guitar - it’s me. I came to understand that those periods are necessary because they show me what I don’t want. And at the same time, they show me what I do want. So I just change my perspective and go on from there.”

I remember way back in the early days of Guitar World, your father would call the office and ask if we were writing something about you. He was almost like your unofficial publicist.

"[Laughs] He was. I was very fortunate to have two parents who were very supportive of me. My father could be tough at times, like all fathers, but he was always very proud of what I was doing. I remember when I was young and playing my guitar too loud, the neighbors would complain.

"He’d tell them to shut the fuck up. [Laughs] He’d say, 'That’s my son up there playing the guitar.' Meanwhile, it sounded like hell. And then my teachers would get upset when I’d bring a guitar to school. They’d call my parents, and my father would say, “My son will bring his guitar wherever he wants. [Laughs]"

A lot of kids back then didn’t have that kind of support.

"It’s true. But I’ll say this: Even if my parents fought me, I still would’ve become a musician. I had no choice in the matter; it was going to happen."

You talk openly about having doubts and insecurities. When you and Joe Satriani were teenagers, back when he gave you guitar lessons, did you two ever talk about that sort of thing?

Joe Satriani and I bonded on a different level than just student and teacher

"I think we were a little too young to be discussing such lofty concepts, but in our own teenage way those messages were being transferred. For me, a lot of them came from just watching Joe. There were all the academics of the lessons, but there was also the cool that he was.

"He’s four years older than me, and he was in high school, while I was still in junior high. He was always cool: He had long hair, he played the guitar, he said cool things and wore cool clothes. I picked up a lot by just being around him. I will say this, though: There was this huge field in our town, and occasionally Joe and I would pull up to it, and we’d look out over it and just talk.

"We called the place 'the Sea of Emotion.' For however deep teenagers can go at that time in our development, that was the place where we had these lovely life discussions. We bonded on a different level than just student and teacher.

You went to work with Frank Zappa at such a young age. It was a great opportunity, but were you intimidated to be around him?

"Oh, my God, yes! On one level it was petrifying. I was 18, and this was Frank Zappa. I was enamored of him. I would watch him and think, 'OK, Frank is reaching for his coffee. What’s he gonna tell me? What the fuck am I doing here?' All those things went through my head. [Laughs] But it’s funny, because at the same time, on a performance level, I was completely different.

"I knew I could contribute to his music, and I was fiercely confident. I was like, 'Go ahead. Give me anything you want. I’m going to play it, and I’m going to blow you away. I am not one bit intimidated, because I know the secrets.' And my secret was just my practice ethic. Give me anything and I will break it down. I’ll learn it perfectly until I can play it with confidence to the point where you’re impressed.

"And I did that. I did things that to this day I can’t believe - things like The Jazz Discharge Party Hats and Sinister Footwear. I loved playing those things perfectly and as beautifully as I could. On that level, I wasn’t intimidated at all."

Soon after leaving Frank’s world, you joined Alcatrazz. Did that feel like a starter band into the big leagues, or were you thinking at the time that it might be a lifetime commitment?

"No, when I joined Alcatrazz, I knew it wasn’t how I would spend my life. But I saw it as a good opportunity to step into the limelight of an incredible virtuoso, Yngwie Malmsteen, and make a rock record with some really cool guys. I never looked at any of the bands I joined as lifetime commitments; that just didn’t seem realistic.

"And this was much to the chagrin or disappointment of my high school band even, because we had a great little thing going, and then I suddenly moved to Boston to attend Berklee. 'Why are you doing this to us and our band that has all these hopes and dreams of fame and fortune?' I loved that band. I’ve said this before: It was my favorite band that I was ever in. Because when you’re in a high school rock band, there’s nothing cooler than that."

So you obviously didn’t see playing with David Lee Roth and Whitesnake as lifetime commitments either.

"No, absolutely not. I loved those guys, and I wouldn’t trade those experiences for anything. But as I was going through it all, I saw how easy it was to get wrapped up in creating an identity for yourself from it: 'I’m a rock star. I’m playing arenas, winning all the polls and making so much money.

I get asked a couple times a month to join bands, and unfortunately, all the situations that have the potential for me to join are relatively insipid

"'It’s who I am, and I’m going to hold on to this forever.' That always seemed like insane thinking to me. Did I enjoy it? Sure, but I also knew it wasn’t what I was going to do all my life, because the music I had in me had to come out; otherwise, my career would be an epic fail."

At this point in your life, would you ever join another band?

"It would have to be an extraordinary situation, with extraordinary people who are looking to do something very artistic, accessible, powerful and different. I get asked a couple times a month to join bands, and unfortunately, all the situations that have the potential for me to join are relatively insipid.

"Now, that’s just my perspective, but it’s the only one that’s valuable. So no, unless those parameters were met, it’s unlikely that I would join another band."

I always loved your playing on the PiL record, Album. You occasionally play on other people’s recordings, but you don’t do a lot of it.

"Sometimes I do. Just recently I played on a Jacob Collier record. It was fantastic, because there’s a guy who’s completely in touch and connected with his inner-creative being in a powerful way.

"When somebody has a creative idea and can express it like that, I’m happy to contribute. I get offered to play on records several times a week. Sometimes I’ll do it as a favor for a friend. But at this point in my life, with whatever time I have left, my main focus is to create the music that’s stimulating to me."

For most of us, our old photos are tucked away and nobody ever actually sees them. However, everybody can see your old photos. Do you ever look back at your hair and clothes in the '80s and go, “What was I thinking?”

In the long run, history doesn’t remember the times when the trends dipped. They don’t remember that when grunge came in, if you had an '80s style, you were a bad disease or something

"[Laughs] There was a period of time when I thought that. Then I realized I knew exactly what I was thinking at the time: 'Let’s get crazy! Let’s do something over the top.' I look at photos from the '80s, and a part of me cringes, but then I remember we were having a blast. It didn’t seem preposterous when we were doing it. It was just fun, and I wore it well. Back then, we were gods. We were entertainers. We wore what we wanted, and we played our asses off.

"Trends come and go, and there’s a point when the trend becomes insipid and is considered bad or wrong. But in the long run, history doesn’t remember the times when the trends dipped. You can see that now with all these people who show appreciation for music of the '80s.

"They don’t remember that when grunge came in, if you were '80s, you were a bad disease or something. I was fortunate enough not to create so much of my identity out of that stuff, so that when I did change my clothes or cut my hair, it wasn’t like I was killing my image or disappointing anybody. Because in the long run, none of that stuff matters; it’s all little stuff."

Have you ever experienced times in your life when you simply didn’t know what to do next, musically?

"There was never a point when I didn’t feel like there was a creative direction for me to turn to. For me, one of my challenges was coming to the brutal reality that all of the projects that I’ve imagined and started could take anywhere from six months to two years to finish. It was like a rude awakening.

"So I had to prioritize, and to do that I had to go deep into my imagination and create something that transcended all of these projects that I wasn’t going to be able to finish.

That’s something I want to put out to everybody: If you feel creative, you have to search for what is unique, vital and valid. To be creative on your deepest level - without any excuses or fear - is what you’re here for. That’s vital to the contribution of everything. I know that sounds lofty and extraordinary, but that’s the way I feel about it. And that’s helped me prioritize.

What matters most is that you’re enjoying the process of your creative expression now

"If you’re enjoying what you’re doing now, what does it matter if you can’t achieve the 300 years’ worth of projects that you want to? None of that matters. What matters most is that you’re enjoying the process of your creative expression now."

You’ve had a huge impact on guitar design. When did you realize you wanted to build the first Ibanez JEM guitar?

"Well, the evolution of the ideas came from the time I picked up my first guitar. There were things I liked about Les Pauls and Strats, but there were things I didn’t like. So I battled with those things until it got to the point when I said, “Why don’t I just have a guitar made that’s exactly what I want?” This was when I was in Alcatrazz. I had run into a little money, and that’s when I really started on the idea.

"When I joined Dave Roth, I needed to have an arsenal of guitars that were relatively interchangeable, and that’s when I designed the JEM. This was before I was with Ibanez. I just made it like a one-off for me, and it was very simple, but it was based on my own idiosyncrasies of playing.

"I took a very practical approach: I wanted 24 frets, very rare at the time. I wanted a deep cutaway so I could comfortably play on 24 frets - also non-existent at the time, basically. The pickup layout and switching system were big ones; I wanted a pickup configuration that satisfied me as a guy who liked both Les Pauls and Strats. The floating trem was an obvious Vai-ism. I wanted to pull back on the strings, so I just chopped the wood away from the tail piece, and there it was - a floating tremolo system.

"The whole thing felt very natural and innocent, and nothing about it really felt revolutionary to me. I didn’t even think anybody else would be interested in it. But that’s just like all art, isn’t it? You have to please yourself."

I assume by that point you had all kinds of guitar companies on your doorstep just begging you to be an endorser.

I said to Ibanez: 'Let’s make it in three Day-Glo colors and put a monkey grip handle in it.' And they’re like, 'What? Are you sure?'

"I did, but I was put off by that. Their idea of an endorsement was, 'We’ll give you a free guitar, and we’ll use your name.' And I was like, 'No fucking way.' But with Ibanez, I thought, 'If I did have a company making this guitar, that would be really nice for me.' I wasn’t doing little cosmetic changes; this was an overhaul of a guitar, in a sense, even though, as I said, it was just my idea for myself."

Even with that said, it was definitely a groundbreaking decision.

"Right. It took me by surprise. I mean, people were interested in it. Because back then, when I went to Ibanez and they brought me the guitar that was a perfect guitar, I said, 'OK, great. Let’s make it in three Day-Glo colors and put a monkey grip handle in it.' And they’re like, 'What? Are you sure?' The president of the company’s scratching his head, saying to his A&R guys, 'Are you sure this Steve Vai guy is the right guy?'"

“Is he just goofing on us?”

"Yeah, 'Is he goofing on us?' Because this seems completely insane compared to what was going on at the time. But I was really quirky and just looking to be different. And surprise, surprise - the guitar hit a nerve. I can’t even tell you what an incredible windfall that guitar has been for me over the last 35 years. It’s been great."

A lot of times I hear artists say, 'I love all my albums. They’re all my babies.' OK, I get that. However, when you look at the studio albums you’ve put out thus far, is there just one that stands out to you as being the best?

"Well, without sounding pretentious, they’re all perfect. [Laughs] On one level, they’re all fine - perfect. When I look back and I hear them, of course there may be certain things that I might do a little differently now, but that’s now - the only time I could do them.

"Having said that, I don’t think it’s uncommon that an artist might feel that their last record is usually for them, their best. And for me, I think Modern Primitive is exceptional. It’s so quirky. It’s so… 'Vai.' [Laughs]"

So let’s say a plumber came to your house. He’d never heard your music before, but he wanted to hear what you do. You’d play him Modern Primitive?

"No, it’s according to what he wanted to hear. If he wanted to hear a guitar piece, I would play him the new thing I recorded last month, which is the last thing I did. It demonstrates my evolution as a player, I think, so that might be what I’d play him."

I guess it’s an impossible question: What one song would define you to somebody?

"Can the song be 90 minutes long? [Laughs]"

If the plumber has the time, sure. But I imagine he’d charge you.

"[Laughs] Probably. See, I don’t think it’s a matter of which song you choose to play. I think what matters is the level of enjoyment you find in playing it, and you can do that with any song."

You don’t churn out albums; you seem to work on them and issue them pretty thoughtfully. Is creating an album always a very dedicated process, or have you ever just banged one out in a moment of complete spontaneity?

"All of the above. Alien Love Secrets came very quickly. I had just come off the Sex and Religion tour, and I was conceiving Fire Garden, which, like many of my other records, was incredibly laborious. I get very specific, and I knew Fire Garden was going to be a huge ordeal of time and intensity.

"So I decided to release a simple trio record right away for the fans who really wanted to hear that kind of thing, because I’d neglected them. I knew what they wanted and I hadn’t been doing that because I was chasing all these other things. I really loved Alien Love Secrets - it was very quick and easy.

"Certain songs on my records are just like that, but other ones are behemoths that need to be built a particular and specific way, based on my inner-ear and my creative desires."

Do you ever engage in those marathon practice sessions from your youth - 10 or 15 hours? Or is there no need for that?

"The intensity of focus shifts to various things. For instance, this morning I woke up at 7:30, which was a bit of a drag, because I like getting up earlier. I got a cup of coffee, walked right into the studio and sat at the computer to continue working on what I had finished at midnight.

"I’d been editing these musical scores that are very dense and intense, and in June I’m going to record them with various orchestras. This music requires a lot of concentration on my part - I don’t just hand stuff off. There’s a 40-minute symphony that has really wild guitar playing and all sorts of stuff I’d written quite some time ago. I composed it and had performed it with the North Netherlands Orchestra in Holland, and now I’m basically re-orchestrating it and preparing to record it.

"So other than speaking with you right now, which is a nice break, that’s what I’ll be doing throughout the day. I’ll be sitting in my studio chair and working until I can go to sleep again at midnight. And I’m perfectly fine with that. It’s work, but I love it. I can’t tell you how grateful I feel to be able to immerse myself in this thing I do. It’s my hope that everybody can find that kind of outlet in their lives… We should all be so fortunate."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.