Steve Vai: “I’m very fortunate in that whatever ridiculous ideas come into my head, the people at Ibanez can make them real”

On his spectacular new album, Inviolate, Steve Vai has created some of the most adventurous, magical and powerful instrumental music of his career. But it wasn’t the record he planned to make at all.

“The way the album came about was a complete surprise to me,” he says. “I was actually working on a solo acoustic album with vocals, something I always wanted to do. I was pretty far into it, but things beyond my control intervened, and I had to switch gears and recalibrate my thinking. I actually had no real choice in the matter.”

Vai isn’t being melodramatic. It was in the fall of 2020 when he noticed that a pain in his right shoulder – one he believes stemmed from years spent hunched over his guitar while growing up, and possibly exacerbated from working out – was becoming progressively worse.

He saw doctors and therapists and tried various treatments, but nothing seemed to alleviate the condition. Finally, he was faced with one option: surgery. “Three tendons had torn, and they wouldn’t just heal themselves,” he says. “When the doctor went in, he said it looked like a hand grenade had gone off. The nurse told me that she had never, in her entire career, seen a bicep tendon in that condition.”

While recuperating, Vai was required to keep his right arm in a sling called “the Knappsack,” nicknamed after his surgeon, Dr. Knapp. Playing the guitar was out – or so he thought – until one day he received a prototype of one of his new Ibanez signature guitars, an Onyx Black PIA (named after his wife).

“It was the most gorgeous instrument I’d seen,” Vai recalls. “I picked it up and my heart was breaking, because I wanted to play it but couldn’t.” Then the guitarist was seized by a mad idea: Why not simply play it with his left hand?

“I always toyed with the idea of writing a song with just one hand. Lo and behold, I was put in a situation where it was either do that or do nothing. So out of this came a new song – Knappsack.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Last year, Vai released a video of himself performing the song. It’s an astonishing clip that captures the guitarist – his right shoulder held immobile in the Knappsack – effortlessly playing one-handed over a galloping rhythm, executing everything from hammer-ons and pull-offs, gorgeous legato lines and wicked whammy bar dives, all of it sans pick.

“At first I thought, ‘It’s cheesy novelty stuff,’” he says. “Just as quickly, I thought, ‘Why not?’ We had everything set up in a way that I could navigate through it all myself, and I thought it would be interesting to film it. I laid down a click track, we turned the cameras on, and I started building the track, doing little pieces at a time. There’s some cheating going on, maybe 20 or 30 seconds. I built the song around the guitar and my desire to play it with one hand.”

Once he recovered from shoulder surgery, Vai returned to his acoustic album, but it wasn’t long till he faced a new problem. While working on a song, he fell into a meditative state while holding what he describes as “a very obtuse chord.”

“I was really trying to focus on the picking and getting every note right,” he says. “This went on for about 20 minutes, and after I released my hand I noticed my left thumb really hurt. I thought I had just strained it and that the pain would go away.” Only it didn’t, and a month later, Vai’s thumb started to twitch involuntarily and freeze up. “They call it ‘trigger finger,’ and for me, it meant that I couldn’t play.”

He went under the knife a second time, this time to repair the flexor tendon in his thumb (“a very easy procedure, thankfully”), and after he had healed he again went back to work on his acoustic album.

One of the pieces he attempted to record required very brisk strumming, and Vai discovered that his right hand wasn’t cooperating – as in, there was nothing there. “It was like I couldn’t connect with the pick,” he says. “At that point, I thought, ‘OK, this is what it feels like at the end of the road. I’m going to have to retire from the thing I love.”

Shut the f**k up and start practicing your ass off. That’s the voice I always listen to, and it’s the correct voice

That thought lasted “about five seconds,” and then another voice took over and Vai told himself, “Shut the fuck up and start practicing your ass off. That’s the voice I always listen to, and it’s the correct voice. I just started playing and playing, and it all came back.”

He put the acoustic album on the shelf (for now) and turned his attention to creating a new batch of electric instrumental songs that would form Inviolate. The album, Vai’s 10th proper studio recording (not counting compilations), is a major work of art, as important a statement as what is generally regarded as his masterpiece, Passion and Warfare.

Clocking in at around the 45-minute mark (designed to fit on a single vinyl album), it’s one of his shortest recent releases, but what he says in that time limit is nothing less than remarkable.

The album starts out with an inferno – Teeth of the Hydra – that comes at you from all directions, violent and unforgiving, full of slashing, jarring chords that feel like uppercuts to the body; yet there are moments of blissful, woozy eroticism – breathtaking harp glissandos and trippy legato melodies – that give off a pulsating and warm glow.

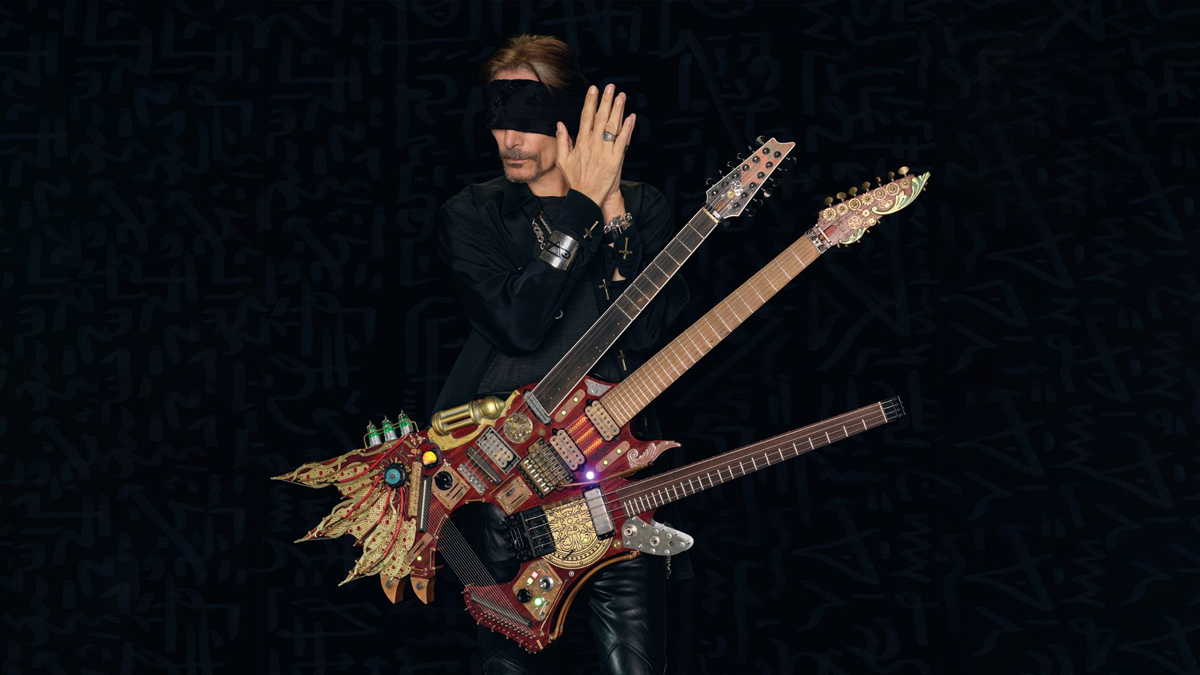

For Vai, who performed the song on a whacked-out, three-necked guitar of his own design, it’s a personal triumph, one that will leave listeners slack-jawed.

Zeus in Chains is an equally disorienting, surrealistic thrill ride. Over a gnashing rhythm, Vai dispatches turbulent riffs, soaring melodies and extravagant displays of fretboard prestidigitation that take flight into a hallucinatory fever dream. Before we’ve had a chance to recover, the guitarist changes things up with Little Pretty.

“Think Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf,” Vai says of this spunky, jazz-tinged gem, and true to his description, it’s both charming and dangerous, brimming with spine-tingling arpeggios over odd-time changes that cast a seductive spell.

There’s high point after high point: on the spacey extravaganza Apollo in Color, Vai’s elastic soloing is highly entertaining poetic drama, and he conducts a guitar exorcism on the relentless rocker Avalancha.

While he admits to keeping the blues at something of an arm’s distance, his Greenish Blues, with its mélange of radiant colors and emotions, is deeply involving stuff untethered by conformity. Vai calls Knappsack and the frisky country-jazz-flavored Candle Power (an earlier cut on which he plays sans pick or whammy bar) the “two orphans” of the album, but they feel fully integrated, as does the deliciously vibey closing track, Sandman Cloud Mist, which had its origins at a 2019 soundcheck. After taking listeners on a dizzying and intense journey, he sets them free, off into the vapors.

For Vai, who utilized the talents of an ace group of players (they include drummers Terry Bozzio, Vinnie Colaiuta and Jeremy Colson, as well as bassists Billy Sheehan, Philip Bynoe Henrik Linder and Bryan Beller, among others), Inviolate represents something of a grand summation of where he’s been musically, but it’s also aspirational.

“As an artist, I try to relish the joy of marching forward with my creative intentions. I always want to go somewhere new,” he says. “At the same time, the ego comes in and I want people to like it.” He laughs. “It’s like the two thoughts are in my head, and I’m always trying to reconcile them.”

It’s interesting that you titled the album Inviolate, which means “safe from injury or violation.” For a time, you were facing both.

“Well, yes, but see, we can get into Vai-isms. Basically, you know that my creative meanderings sometimes circle around spiritual concepts and things. So, OK, there’s the world stage that we believe is what’s really happening, and for many of us, that’s the truth. But there’s something else going on, and that’s the human spirit.

Your awareness is untouchable by anything in this world, because it’s not part of this world

“The human spirit is inviolate. It doesn’t contain the neuroses of conditioned thinking that the world is basically a slave to. It’s part of everybody. You’re not your body; you’re your awareness. Your awareness is untouchable by anything in this world, because it’s not part of this world. Your body is part of this world. So your spirit, so to speak, is inviolate. It cannot be touched or harmed.”

There you go. Let me ask you, once you had to shift gears away from the acoustic album, did you have a clear agenda for what you would do on this record?

“Good question. In the past, I would try to exaggerate the record’s presentation with stories and concepts. When I came out of the surgery, I had a tour and a release date coming up, and I just sort of jumped into these songs that I had. It was almost like not planning, but navigating in the moment of inspiration.

“Take a song like Apollo in Color. It may sound a little fusion-y, but for me, it was a melody that I had on the shelf for years. Every time I’d come across it, it would scream out, 'Please record me.' So that was the criteria. I went for the best ideas that needed to be birthed in that moment.

“Much of it wasn’t planned, like Candle Power and Knappsack. With Candle Power, I had this concept for doing a song that was different from how I normally approach a song: it was a clean guitar, no whammy bar, and I was using my fingers to pick. All very abnormal for me, and I’m not a good fingerpicker. But I wanted to challenge myself.”

Did recording that song make you think you rely too much on heavy distortion and the whammy bar?

“Not really. I like my style. I like the tone and the quirkiness of my playing. Heavy distortion, delay, whammy bar antics – that’s what I like.”

Obviously, there’s benefits to having your own studio; you can always get in. But is there a downside to being there too much? Do you ever have to tell yourself, “Step away from the console, Steve”?

“Nope. This is where I love to be. It’s my jam. I’ve always had studios at my homes; otherwise, I wouldn’t have a family life.”

I’m very fortunate in that whatever ridiculous ideas that come into my head, the people at Ibanez can make them real

Let’s talk about Teeth of the Hydra – but we also have to talk about that guitar.

“The guitar… I’m very fortunate in that whatever ridiculous ideas that come into my head, the people at Ibanez can make them real. I was thinking of the movie Mad Max; there’s a scene in which this guy is playing the guitar on the front of a truck. I started to think, 'I want to build a guitar that has an alien-like vibe, but with three necks and harp strings. And I’m going to create a piece of music that uses all of them.' It came to me in a flash. I was looking into steampunk at the time.

“That was the idea. The top neck is a 12-string, and half of it is fretless. Then there’s a seven-string neck, and there’s a bass neck with the E and A strings being fretless. I took the idea to Hoshino and mentioned 'steampunk'. A short while later, they sent me a rendition and some illustrations, and it went from there.

“They added some accoutrements – some I asked for; others they put on. It’s got piezos, sustainers, lights, sample and hold features. It started about five years ago, but the whole thing probably took a year and a half. I was stunned that they could make the thing.”

Did you know what to do with it right away?

“It sat in the studio for a year. I’d walk past it and go, 'One of these days, you’re mine. I know what I’m going to do. We’re going to do it together.'”

Are you playing the Hydra throughout the song in one live pass?

“Each section is live, but I didn’t do it entirely in one pass. I was writing it and building it as I was going. You know, we created this makeshift stand for the guitar; the thing is really heavy. But we designed this waist strap that holds it, so all the weight is on your hips and not your shoulders.

“The whole thing is so funny. I would sit with the guitar and just look at it like, 'What are you thinking? How are you going to do this?' And then there’s that other part that says, 'Shut the fuck up and just do it.' If you want to do something impossible, you just have to start doing it.”

There are many brilliant elements in the song. Those brutal chords jump out so forcefully.

“Thank you. Everything you hear on that song – with the exception of keyboards and percussion samples – is the Hydra. The goal was to have a piece of music that doesn’t sound like it’s being performed on a novelty instrument, or that it’s a disjunctive melody.

“When you see how I performed this piece, it’s so entertaining, because I had to negotiate the left-hand pull-offs so that the melody sounds uninterrupted – like a real melody. It was crazy, but I did slowly, a section at a time. It took two months.”

You used a Gretsch on Little Pretty.

“An Anniversary model. I’ve always liked Gretsches for their sound, but they’re not really my jam. Still, I had this riff and I thought, 'It has to be played on a Gretsch.' They’re beasts, those guitars. For me, they’re hard to play. They put up a fight, but that’s the challenge.”

I love the odd changes in the song, especially in the solo section.

“The solo section is a killer. I sat down and said, 'You’re going to create changes that in and of themselves sound great together, but every single chord change is a completely different synthetic mode.' There’s nothing conventional in those changes, and they’re death-defying to solo over. I didn’t want to sound like I was soloing over jazz changes.

“A lot of bad jazz is people outlining chords at the speed of light, and that just doesn’t do it for me. I hear fusion-y type playing that just follows chords and theoretical absolutes. That’s fine, but it doesn’t push my button. With that solo, I said to myself, 'This has to be musical and melodic, but it has to work in these chord changes that are so bizarre.'”

I never saw myself as an authentic blues or jazz or fusion or even rock player

Before our interview, you told me about Greenish Blues and said, “It’s my take on the blues. It’s the closest I desire to come to it.” You have to elaborate on that, because as you know, blues is at the root of rock music.

“And yes, it’s at the root of everything I do. The first scale I ever learned, and everything that I do, is based off of that scale and manipulations of it. But as far as conventional blues, when I was younger, I wasn’t a big fan. I was more into rock. As I got older, I started to appreciate the blues when it’s performed very authentically.

“But I was never very authentic at it. I never saw myself as an authentic blues or jazz or fusion or even rock player. When I decided to do Greenish Blues, it originated at a soundcheck. We just started playing and things happened. I liked it, so I decided to do it in the studio. And I just told myself, 'Don’t try to be authentically blues.'”

But what’s authentic?

“All of the blues-type playing that people believe is approved and appropriate. Like, if you listen to Stevie Ray Vaughan, that’s incredibly good rock blues. Oddly enough, I was walking through the house the other day, and there was some blues playing. The guitar playing was really good and tasty. It was John Mayer.”

The guy can play.

“Yeah, but I don’t do any of that stuff, and I don’t want to try. As I said, Greenish Blues is the closest I care to come. It would be inauthentic for me to try to do what those guys do. I’m not good at it. If you had my weird, quirky instincts, would you choose to try to sound like something that’s been done a million times by people who breathe it?”

But isn’t the point to take it somewhere else, like, say, Jimi Hendrix?

“Yes, but Hendrix took it to where it was comfortable for him. And I kind of took it to wherever it went for me. Let me ask you, when you listen to Greenish Blues, what do you hear?”

I hear spirit… joy… excitement. I hear somebody telling me a story.

“There you go. Thank you. And if I tried to sound more authentic to the blues, we’d miss all that.”

Fair enough. Let me ask you about Knappsack. When you eventually play the song live, are you going to do it all with one hand?

“[Laughs] I was afraid you were going to ask that. I have mountains of guitar work to do for this tour. Teeth of the Hydra, Candle Power... it took weeks to get that riff. Then there’s Knappsack. I watch the video and I think, 'How did you do that? How the hell are you going to negotiate all these guitar parts? You can’t. You’re not going to be able to do it.'

“And then that other voice comes in and says, 'Shut the fuck up and just do it.' For Knappsack, the vast majority of it will be on one hand. If I use my right hand at all, it’ll be to mute strings in certain parts. One of the other things you don’t see in the video, for some of those riffs I used the Sustainer. That’s where all that sustain came from, on some of those really fast, Indian-style finger legato things.”

Sandman Cloud Mist is so beautiful and vibey. Like Knappsack and Candle Power, you had parts of it earlier, right?

“Yeah, it was just a chord progression that I wrote for the Big Mama Jama Jamathon [which took place in 2018]. And then I was doing a video demonstration about delay. I do this Patreon thing that I really enjoy – it’s like a holding tank for creative ideas.

“One of them is an episode in which we go deep into all the parameters on how to build delay, where it sits in a signal chain, all that stuff. To demonstrate heavy delay, on one of the patches I recorded and videotaped about 20 minutes of playing over a vamp.

“I edited it down and really liked the way it sounded. It was a different kind of a voice to me, because most of the time, when I’m building something in the studio, I work on it, work on it. I tweak and refine, and then I go, ‘OK, it’s good.’

“There was none of that with Sandman Cloud Mist. It was pure playing in the legato style that I do. But I didn’t want to use a loop, so I had Vinnie Colaiuta lay down the most beautiful drum track. It gave him an opportunity to do some polyrhythmic playing that I don’t think he gets much of a chance to do on his conventional big gigs.”

Besides the guitars we talked about, which other models did you use on the record?

“Other than the Hydra, the Onyx Black PIA, the Gretsch… On Knappsack, I used FLO III with a Sustainer. On some things, I used a Strat-type guitar that Ibanez made for me.

“I’m a big Strat fan from my childhood, and I’ve got a great little collection. They’re not vintage, but they’re ones that I’ve kind of collected. Strats are hard for me to play, and they don’t really suit my style entirely. I’m fortunate in that I can I call Ibanez and say, 'Can you make me a Strat that suits my style?' They’ll build something, but it will never really be a Strat.”

As you get older, would you say you’ve noticed your playing evolving in any important ways?

“It’s funny how things work out. It’s all mental. I think naturally, as we grow older, our perspectives change. We can go from a very progressive mentality to a more conservative one, but you can retain aspects of all of them. You just do them differently. I don’t feel the need to have to blow up every song. You know what I mean?”

You’re now in your 60s. With age, do you feel the urge to be more prolific?

“That curse plagued me for a good part of my life. Strangely enough, again, for the last five to eight years, it’s also dissolved. There will never be enough for the ego. You’ll never be able to satisfy the unending thirst to express yourself creatively.

“It won’t go away, but the feeling that you’ve got to get it all out now is panic mode. What matters is how you feel the moment you’re creating music – or whatever you’re doing. If you’re looking for it in the future, it’s never going to come, because you’re always looking for it in the future.

When I turned 50, I looked at all of the lists of projects I’ve accumulated through the years that I wanted to accomplish, and I realized they were pipe dreams and fantasies

“When I turned 50, I looked at all of the lists of projects I’ve accumulated through the years that I wanted to accomplish, and I realized they were pipe dreams and fantasies. I could do one project a year, and the reality was, I had 100 of them.

“And I just thought, ‘OK, you have to rethink this, Steve. You’ve been doing your best to be creative, and what’s been coming out is pretty appropriate for the time. So just continue. Don’t worry about all the stuff you want to release that isn’t going to be released, because it’s all contained in each project you do.’ I think that makes sense.”

How do you feel about finally hitting the road again?

“I’m excited to get out there, more than I ever have been. This is going to be the most challenging tour, for many reasons. But you know, I used to fill myself with stress: ‘Are you at your best? Are you giving people everything you can?’ Sometimes it almost made me want to put off going on tour.

“Like everybody, I had to cancel and postpone all sorts of gigs because of the pandemic, and I was totally fine with it. I’ve been a touring musician for 41 years – long time. But a little while ago, I got the itch to go back out.

“Because the reality is, I love touring. I get to see the world with a traveling family, and most of the time – like, 90 percent of the time – it’s pure fun. I get to go to different places and taste different cultures.

“In my younger days, I didn’t always appreciate it. That started to get to me, and I thought, 'There’s going to come a day when I won’t be able to tour, and that will be a sadder day for me than the day my fingers say, “I’m done with you.”' So I’m excited to feel that pull once again.”

- Inviolate is out now via Favored Nations.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.