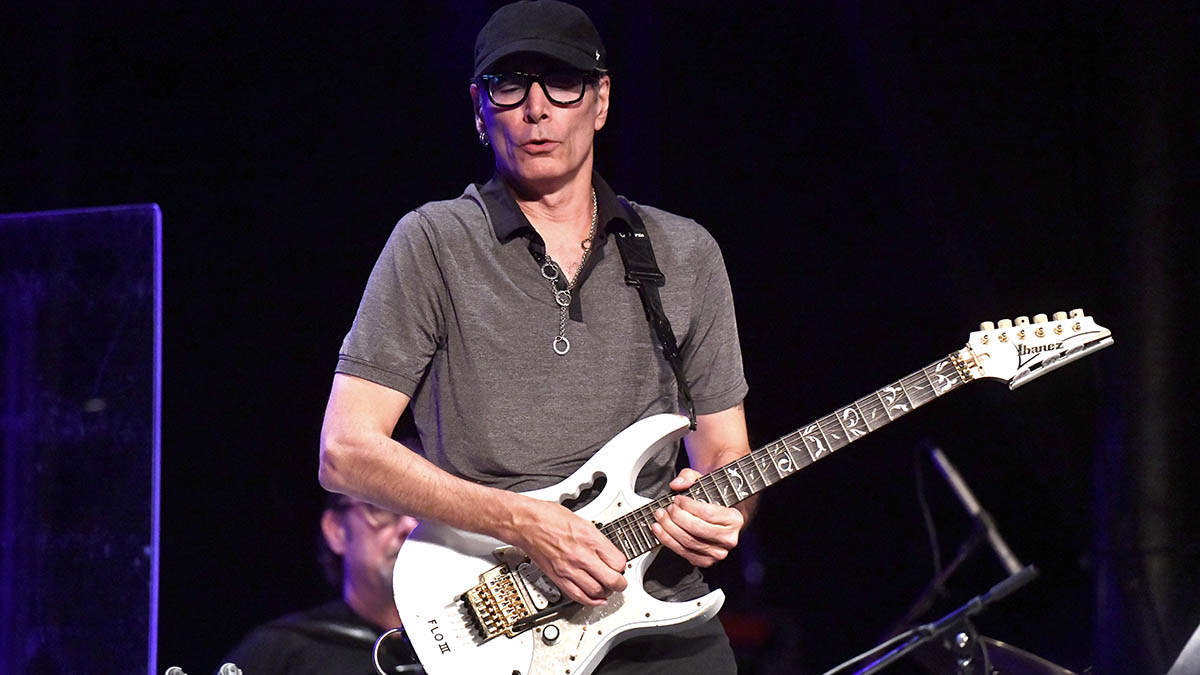

Steve Vai on how Frank Zappa inspired him to design the Ibanez JEM – and why the Japanese guitar builder succeeded where others failed

“Ibanez said, ‘We want to make these for other people, too.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Who’s going to want this? It’s so weirdly idiosyncratic to me!’”

Since developing the Ibanez JEM in 1987, Steve Vai’s ability to guide his artistic vision to fruition has always been strong.

Here, he reminds us of the strides he took to bring the initial JEM guitar to life, and why – after three decades with this original signature guitar – he decided it was “time for a little change” with the PIA.

The JEM has been around for 35 years. At the beginning, why did you feel the need to develop that guitar?

“I was fortunate working for Frank Zappa because one of the things I learned from him is if you want something, just do it. So Frank was molesting his guitars with electronics and putting things in them, like frequency modulators and parametric EQs, and I’m changing the necks, changing the pickups.

“I thought, ‘Well, that’s what you do. You find what you want.’ I loved Strats because they had a whammy bar, but I didn’t like the way they sounded. They weren’t rock ’n’ roll enough to me. I loved Les Pauls because Jimmy Page played a Les Paul and they had a better sound for me, but they weren’t sexy to me. They felt awkward and none of them you could really comfortably play in the high register. I don’t know why they give you the frets when they don’t give you the access to them.

“I knew that I wanted to have something that was not necessarily one of those. Edward [Van Halen] came out with a humbucker on a Strat-style guitar, that was perhaps the first SuperStrat. That was fantastic because now we can get a really good, big fat sound with a whammy bar. But there were things about that guitar that were very limiting to me. So very innocently I decided, ‘What do I want? I could have anything made.’”

Were you thinking about this potential guitar purely on a personal level at that stage?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I didn’t think, ‘I’m going to design something here that everybody’s going to love, and it’s going to make me a lot of money.’ None of that. It was just, what do you want? I went down to Charvel, met Grover Jackson. He gave me a guitar that turned into the Green Meanie. It still was missing a lot of the things I was looking for, but it had humbuckers.

I had a floating tremolo and you could pull up on it and break the string if you wanted and, to me, that’s a good time

“I knew that I wanted 24 frets, which was very rare at the time. I didn’t know any guitars that had 24 frets – and I think maybe the Jackson was one of the first. I knew I wanted my hand to be able to comfortably fit without any obstructions. I knew I wanted it to look sexier than a Strat or a Les Paul in my mind. And I knew I wanted a pull up on the bar, and no guitars did that.

“So I actually took a hammer and screwdriver and I chiselled out all this shit. Next thing you know, I had a floating tremolo and you could pull up on it and break the string if you wanted and, to me, that’s a good time.”

What about the pickup configuration?

“I really liked that ‘tubey’ Strat sound with the two single coils. I had to make the five-position switch so when it’s in the neck position, you get the full-on neck humbucker. When you click it to the next position, it splits the coil on the humbucker and you get two single coils, so you get that Strat-y sound.

“Then the single coil in the middle, if you ever wanted it, I never use it. Then the next position splits the coil on the treble position; that’s the Strat sound I always liked. And then you’ve got your full-on humbucker in the treble position. So they tell me that was unique at the time. Also, I can never understand why the input jack in a Strat or a Les Paul is built so that if you step on the cable, the thing pulls out. It’s like, duh, put it on an angle.”

So, how did the handle come about?

“Joe Despagni was a kid that was my best friend since before kindergarten. All through the rock ’n’ roll high school years, Joe and I were inseparable. And he was one of these MacGyver tinkerers and he was starting to build guitars, too. He was the first one to put a handle in the guitar when we were kids.

“I didn’t assume to put it in the JEM until a little later. There were four that I made, prototype JEMs. I took them on tour with Dave Roth. And once I joined Dave’s band, all the guitar companies wanted me to endorse them, but I just felt like, ‘Thank you. But I have my guitar.’ They were like, ‘We’ll make that guitar for you.’

“I sent the schematics to a whole handful of the big companies that were interested [in making the guitar] and they all fucking flopped. They sent me their guitar with my name on it and some little tiny adjustments and I’m scratching my head going, ‘Why are you sending me this?’ Except for Ibanez. In three weeks, man, they made a JEM and they made it exactly the way I wanted. And that was it. I said yes.

Poor Ibanez, I said, ‘This is the guitar, but I want a Monkey Grip in it. And also dayglow colours’

“They said, ‘Well, we want to make these for other people, too.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Who’s going to want this? It’s so weird, weirdly idiosyncratic to me.’ And they said, ‘Well, Mr Steve, we think a lot of people.’ So I thought, ‘There are some interesting aspects of this guitar that will probably be borrowed and that’s fine. That’s how it works. So I have to do something that nobody’s going to have the balls to steal.’

“That’s when the Monkey Grip came in. At first, I put it in because we were shooting a video with Dave Roth and I wanted to have something where I could take the guitar and spin it around. But then there was something quirky and very Vai about it. Poor Ibanez, I said, ‘This is the guitar, but I want a Monkey Grip in it. And also dayglow colours.’”

What was the reception when the production model was released?

“Part of my agreement with them was that they could release a lower-end model because the JEM was very expensive, and that turned into the Ibanez RG. Lightning struck because it hit a nerve with all the players. It became the No 1 metal rock guitar for many years. And the RG was, I think, either the second or the third biggest-selling guitar in a given year. It’s usually a Strat, Les Paul and an RG of sorts, and the JEM has just had incredible staying power. “

And now you have introduced the PIA. How did that come about?

“After 30 years of me playing the guitar that is completely comfortable for me, it was time for a little change. So the first thing I knew I wanted to mess around with was the grip. Do something a little more artistic. That took a while, a year and a half of coming up with the teardrop cutaway.

“The yin and yang and positioning. Just the positioning alone took a long time because then we decided to take these dimensions – and even their relationship with one another – and incorporated them into the rest of the body. All of these designs here, they’re based on the ratio of these petals.”

And the back cover snaps on with magnets instead of screws?

“Yes. I’m not a fan of guitars that require tools to do anything. For decades, I’ve been trying to find somebody who can create a nut that eliminates the need of a tool, especially changing strings and stuff like that, but I just haven’t met anybody smart enough to figure it out.”

It’s like if the JEM is a teenager, this is like the grown-up version, right?

“That’s the young adult. The PIA is a very pleasing-to-the-eye guitar.”

Robin Davey is is an English-born, LA-based musician, record producer, musical director and videographer. Robin formed UK blues rock band The Hoax, who were signed to East West records in the mid-90s. Other bands include The Davey Brothers, The Bastard Fairies, Well Hung Heart and blues rockers Beau Gris Gris & the Apocalypse, who also feature his partner Greta Valenti on vocals. The two run a video production house, Growvision, and produce our Pedalpocalypse series.

“It holds its own purely as a playable guitar. It’s really cool for the traveling musician – you can bring it on a flight and it fits beneath the seat”: Why Steve Stevens put his name to a foldable guitar

“Finely tuned instruments with effortless playability and one of the best vibratos there is”: PRS Standard 24 Satin and S2 Standard 24 Satin review

![A black-and-white action shot of Sergeant Thunderhoof perform live: [from left] Mark Sayer, Dan Flitcroft, Jim Camp and Josh Gallop](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/am3UhJbsxAE239XRRZ8zC8.jpg)