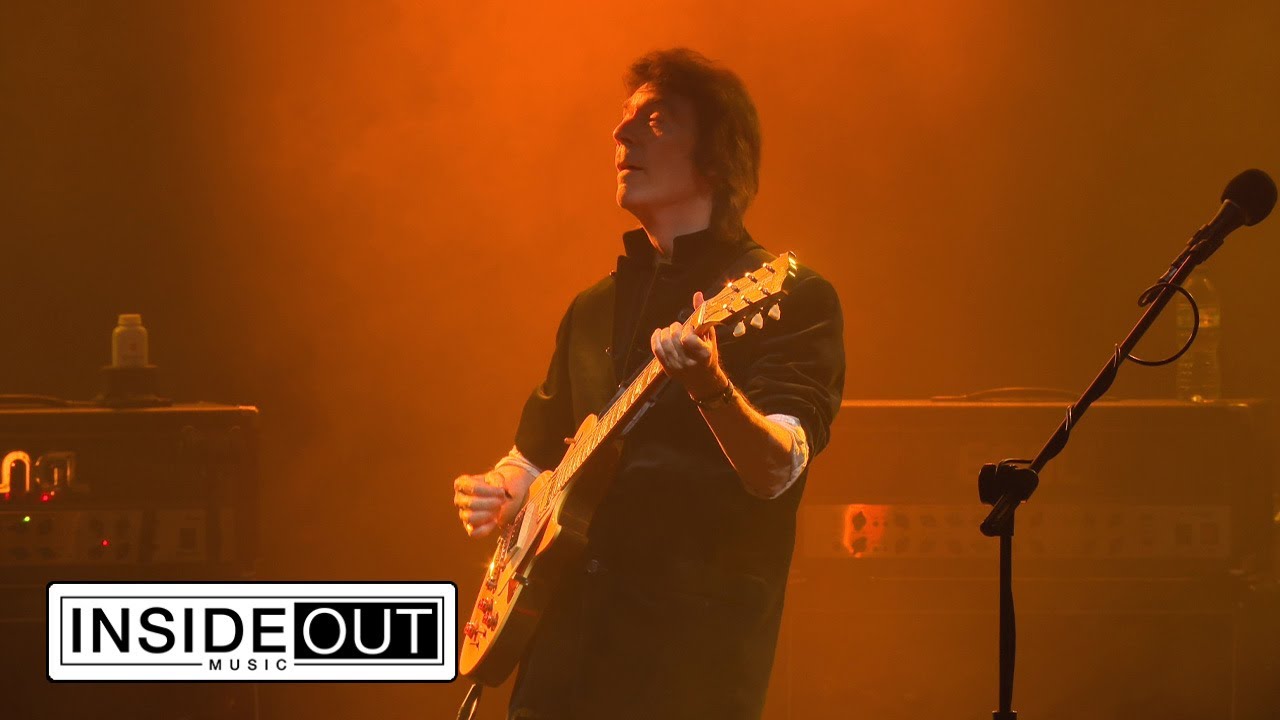

Steve Hackett on discovering two-hand tapping: "It's the guitar-playing equivalent of splitting the atom – it influenced more people than I could have possibly imagined"

One of prog's greatest players reflects on pioneering the revolutionary soloing technique, and shares his thoughts on the Genesis reunion tour – and what the band would have sounded like had he stayed

Considering his status as a legend of prog rock and an extraordinary composer, it's hard to believe that Steve Hackett, in some ways, aided in inventing good-time hair metal.

Now over 50 years since he first came onto the scene, Hackett is known for a myriad of stunning techniques, but his two-hand tapping remains his calling card.

"When I first developed the two-hand technique, I didn't know that others had picked up on it," Hackett recalls. "I was blown away once it started happening all over, and it was so influential. Let's put it this way: it influenced more people than I could possibly have imagined. It's still part of what I do, but obviously, it's not the whole thing. I'm very happy to have freed up guitarists to play dazzling solos and come up with things that would only be dreamt up at one time."

Trailblazing techniques and swells of virtuosity aside, Hackett played an integral role in the rise of legendary prog outfit Genesis, a band whose songsmith was matched pound for pound by its musicianship. Though Genesis boasted a strong '70s-era lineup – Tony Banks, Mike Rutherford, Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, and Hackett – it was the young guitarist's distinctive stylings which oft-defined the group's sound.

Despite its excellence, the core of Genesis began to deteriorate, finding Gabriel departing in 1975 and Hackett following suit in 1977 after the success of his solo career.

"Once I had a successful solo album, which I had with Voyage of the Acolyte, I felt less like asking permission from others to go ahead and bring songs to fruition," Hackett admits. "You have to remember, I wasn't a founding member of Genesis, although I joined very early on. I absolutely loved and adored the songs that we did together; I was starting to loathe the band's internal politics."

Hackett continues to push forward these days, creating immersive soundscapes for listeners to dive deeply into. But the duality of his career isn't lost on him. Once a stage-roaming prog-rock titan, it appears that Hackett still has it in him to harken back to the heights of his Genesis years.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

But would Hackett consider climbing on stage with his old cohorts once more?

"I think we came up with some wonderful things in Genesis, and I'm proud of that," Hackett says. "There were some great writers involved with Genesis when we had the five guys, all capable of writing stuff. Never mind the playing, which truly left us with the best of both worlds. It was incredible. That might have lasted for a while, but that's over now."

Resolute in his vision as he moves forward, Steve Hackett dialed in with Guitar World to recount his final days in Genesis, the inception of his two-hand tapping technique, and his thoughts on the potential of a '70s-era Genesis reunion.

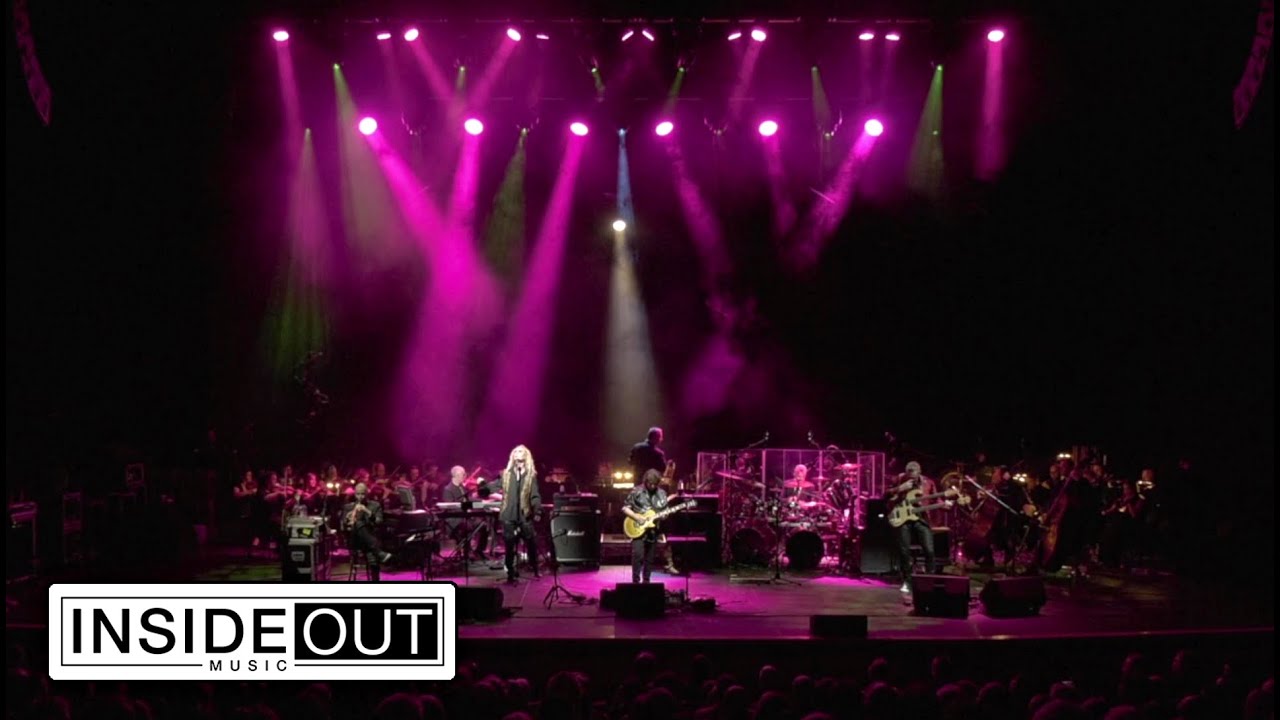

You've recently revisited Genesis's classic live record, Seconds Out. Why now?

"It was a combination of things. I suppose it seemed logical to do this because these songs mesh so well with my solo material. It's also a case of wanting to do favorites and balancing that against my want to play the new material. These songs provide a certain flow and continuity to my show. Seconds Out was and is a colossal album in the UK, and I felt it was time to revisit it properly."

Would you say this is more for your fans than for you?

"In a way, yes. It's all the stuff that I felt they deserved. In other words, the fans who weren't comfortable with the band's direction after a certain point, which I like to think of as the disenfranchised early fans of Genesis, it was a need to try and satisfy them.

"Seconds Out was always an album that encompassed most of the classic '70s Genesis era. So, my thinking was that if I revisit that, I'll make a lot of fans happy. I wanted to deliver this sort of show for fans who have missed out on a lot of gigs due to COVID."

Seconds Out marked the end of your time in Genesis. How do you look back upon its significance?

You've got my era of Genesis, which had longer, more complicated compositions with virtuosic things. And then, once I'd gone, you had simpler songs that were more akin to pop music

"I think Seconds Out is the bridge between two eras. You've got my era of Genesis, which had longer, more complicated compositions with virtuosic things. And then, once I'd gone, you had simpler songs that were more akin to pop music. What I liked most about Seconds Out is that it featured a lot of the most accessible songs from my era, which made it a fun listen for those who don't favor complex music.

"By the time Seconds Out was released, even toward the end of my time, Genesis was becoming more accessible for those who wanted to sing along. But also, there was a lot in it for those who wanted to take up keyboard, drums, guitar, or whatever. I think that split-personality, if you will, was part of the album's success, which is why it sells so well and continues to do so."

What led you to walk away from Genesis?

"I sweated blood to make sure that Genesis became an international success. At the same time, I started making solo albums, which fell foul in terms of band politics. So, I was explicitly told by the others that I couldn't pursue a parallel solo career. And I thought, 'I haven't any guarantees that my songs will be done by Genesis. What am I waiting around for?'

"For me, the mindset was, 'Here's this great band. Wouldn't it have been nice if we'd managed to keep it together with Peter Gabriel? Wouldn't it be nice if it continued to be a four-piece with me?' The politics were becoming increasingly restrictive, and I felt that nobody allowed me to own the music.

"I couldn't afford to have my brain children fall by the wayside. I said to myself, 'I must be allowed to express myself fully musically.' It came down to band loyalty or my own self. I chose myself. I know I made the right decision. I couldn't have stayed in that suffocating atmosphere any longer."

It's been said that you avoided Phil Collins while mixing Seconds Out, as he was the only one who could have changed your mind. Is there any truth to that?

"Absolutely. That is 100 percent true. I avoided Phil – which I felt bad about – because I knew he'd have gotten to me and kept me in Genesis. I knew he would probably talk me into staying, and I thought, 'I can't afford to stay with Genesis when I know it's so restrictive at this point.' So, that's absolutely true. I felt so close to Phil and his spirit, but I knew I had to leave.

I look back on it, and perhaps we could have carried on if we weren't so young and a bit more mature and less cocksure

"And, of course, everybody started to have solo albums once I left [Laughs]. I think that that sort of splintering can't be undone once a band starts to hemorrhage members – a five-piece being whittled down to a four and then to three. It's sad, though. I look back on it, and perhaps we could have carried on if we weren't so young and a bit more mature and less cocksure."

Had you stayed with Genesis, what direction would you have taken?

"I would not have gone in the pop direction they did in the '80s. Although the music's different, I think that Pink Floyd combined lots of soloing, extended arrangements, and many accessible songs. I believe Genesis aimed itself in the direction of vocal-based accessible songs and stripped away the detail. And that meant musicians were no longer looking to Genesis for innovation.

"While that certainly pleased MTV's gods, and it was media-friendly – and I'm not knocking the fact that it's sold millions – I would never have gone along with that. So, my counter to that was forming GTR With Steve Howe. We managed to do something that pleased the gods of MTV, and at the same time, we managed to do something where, although perhaps there was less soloing and more direct songs, bridged that gap. I suppose I might have taken Genesis in that same direction had I stayed."

Describe your compositional approach as a solo artist.

"I look at writing music on guitar as if I'm writing a book. There's got to be a beginning, a middle, and an ending. But there's a lot that happens in between, too. I'll sit down with my bandmates or even my wife and put together a framework for a potential song. And then I load that into my computer, and I play around with it until I understand what it will be."

How has that changed from your days in Genesis?

"I'm freer now, I think. If you were asking Tchaikovsky or Bach to go into the rehearsal room with a bunch of young guys, I don't think that would improve things [Laughs]. If you've got a clear-thinking, conceptual brain, then you can bypass that process. Musicians come into their own once they are let loose on material that's been thoroughly composed through their own filter, and I am much more able to do that now than when I was in Genesis.

"When I was in Genesis, we fleshed things out in a rehearsal room and then kicked it around like a football. We weren't mature musicians back then – we were kids. It's different now when I do get people involved. Once I have the full portrait, so to speak, I've learned to be flexible in terms of how it progresses from there. I leave room for others to be involved. For a composer and a writer, the camaraderie between the people in the rehearsal room reigns supreme."

As both a guitarist and composer, how do you reconcile the two?

You can make a guitar sound like so many things if you've got the patience. Blazing heroics will take you so far, and they don't mean you're capable of writing a good tune

"Well, let's put it this way: I listened exclusively to solo instrumentals when I was very young. And over time, I came to appreciate what each instrument can do within that context. You might think of something simple like the humble triangle and say, 'What's the point of that?' But then you realize that the triangle plays a vital role within an orchestral picture, but it might come in and out.

"So, that thinking altered my perception of how I view myself as a guitarist. You realize just how wrong you can be and that it's all about the context. Like many instruments, the guitar can impersonate other things, like the human voice or even sounds in nature like rain, birds, etc. Once you open yourself up to the idea of imitation in music, the possibilities are excellent. So, as a guitarist, I'm often thinking outside the box and trying to find ways to push the instrument's boundaries.

"Guitars are fantastic lead instruments; they're very adaptable. They're a bit like a synthesizer but without all the weird electronic aspects. You have to have a vision with it. You can make a guitar sound like so many things if you've got the patience. Blazing heroics will take you so far, and they don't mean you're capable of writing a good tune."

You're known for your Les Paul Goldtop. What first attracted you to Gibson's classic single-cut?

"When I was a young guy in my mid-teens, I was aware that in the mid-1960s, all the sonic developments happening within the world of the guitar were usually through the hands of blues players. And it seemed like the go-to combination at that time was a Gibson Les Paul and a Marshall amp.

"Even at a young age, I realized that other individuals invented all these things, but that incredible combination worked very well for so many of the heroic blues players that the British guys were copying. Most importantly, at the time, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Peter Green were using that combination. It was so heavy and sounded so incredible to my young ears. I knew I had to have one for myself."

You branched out to Fernandes guitars, though. What led to that?

"That's true; I have. Fernandes is a wonderful company that also makes its own version of the Les Paul. Meaning it's the same shape and aims to be, essentially, the same guitar. The great thing about the Fernandes Les Paul is that it utilizes the same shape as the Gibson, but it's got a Sustainer pickup.

"I believe other larger companies are using Sustainiac pickups now, too, but Fernandes was one of the first to do it on a Les Paul-shaped guitar. Perhaps Gibson will fight back and do it, too, bringing things full circle for me, but I haven't had a Gibson model with a Sustainiac pickup yet. It would be very interesting to see if Gibson achieved tonal quality."

What other guitars are in your arsenal?

"I've mainly got three electric guitars. I've got a bunch of nylon-stringed stuff, but as far as electric guitars go, it's my '57 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop, the Fernandes Les Paul that I got in Japan, and I have one of the guitars that my friend Brian May invented way back in the day.

"The guitar that Brian made has got a very interesting sound to it. With the pickups it has, it allows me the ability to be able to switch them in and out of phase. With that guitar, I get a big tonal range that can handle everything from country to screaming rock. So, those three guitars are significant to me."

When you developed your two-hand tapping technique, could you have imagined that it would be imitated en masse?

Two-hand tapping is an extraordinary technique, becoming the mainstay of many heavy metal players. I suppose I'm thrilled to have been the granddaddy of that

"I was so young when I discovered that, and I just thought it sounded brilliant at the time. No, I never could have imagined it. I was just messing around, and one day, I realized then when you're hammering on and off with your right hand – which became an important technique because it enables you to play incredibly fast – I remember thinking about it and coming to the idea that I could do something on one string without necessarily having to move to another. And then, when I applied that to the whole of the fretboard, I found that I could do some incredible things.

"It's an extraordinary technique, becoming the mainstay of many heavy metal players. I suppose I'm thrilled to have been the granddaddy of that."

Do you recall the moment that you discovered the technique?

"I can't recall the exact moment, but I remember how it made me feel. It's probably the guitar-playing equivalent of splitting the atom. Just to feel that it's possible to be able to do something that, at one time, only keyboard players could do, was exhilarating. And now, for over 50 years, it's been a part of the rock 'n' roll vocabulary.

"Thinking about it, I first recall doing it in '71 on Nursery Cryme. I recall that I struggled to play it in time, but I practiced it live during some solos with Genesis, and that's when other people picked up on it. I didn't realize its significance in the universal sense back then. At the time, I thought it was personal to me and that I was the only person doing that."

Genesis wrapped things up in the spring of 2022. You were invited but couldn't take the stage. Do you regret that you couldn't perform with Genesis one last time?

Many people love the idea of a reformed Genesis that involves myself and Peter Gabriel going out on tour. First, I'd say that it's been a long time coming. Second, I'd say that I think it's highly unlikely

"The truth is, I had already booked my tour throughout the world, and they booked their tour after I'd done that. I wasn't in a position to offer anything to them at that point because I had all my professional commitments lined up. And look, there's plenty of it on YouTube; you can see what they were doing live and what my band was doing at exactly the same time. All I can say is that I'm very proud of the reviews that we got and the attendance that we had.

"So, I don't think it's a case of separate camps; it's just that I know they've said officially that they won't do any more shows. And we know it's for all sorts of reasons, don't we? It's well known about Phil and that this was to be a sort of last hurrah, as it were. But at the end of the day, there's nothing to stop anyone from deciding to go out again and reform and what have you."

If that were to happen, would you be open to participating?

"Considering Phil can't do it anymore, I know many people love the idea of a reformed Genesis that involves myself and Peter Gabriel going out on tour. First, I'd say that it's been a long time coming. Second, I'd say that I think it's highly unlikely. But as I say, I choose to celebrate the music we created rather than contest it.

"Who knows if the Genesis flag will ever fly again? I choose to fly my own flag in my own way. The ship is still afloat, and I aim to keep it that way. There will be more touring this year; we'll be back in the States in 2023 and then back in the UK in 2024."

- Genesis Revisited Live: Seconds Out & More is out now.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

“His songs are timeless, you can’t tell if they were written in the 1400s or now”: Michael Hurley, guitarist and singer/songwriter known as the ‘Godfather of freak folk,’ dies at 83

“The future is pretty bright”: Norman's Rare Guitars has unearthed another future blues great – and the 15-year-old guitar star has already jammed with Michael Lemmo