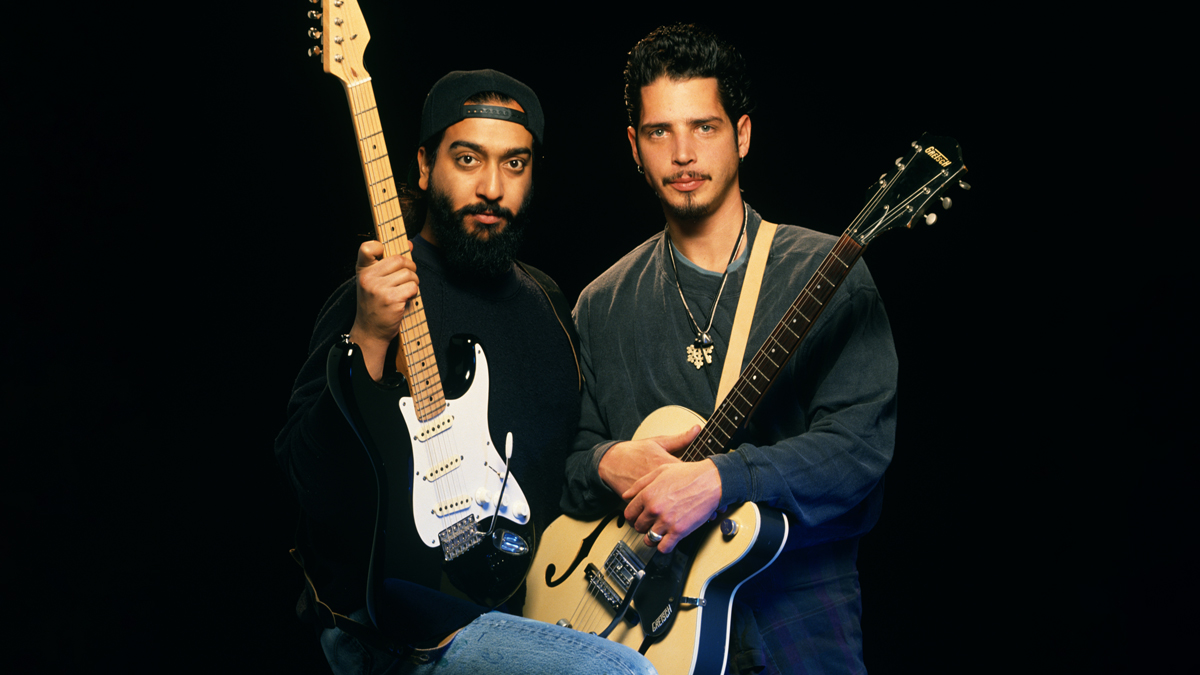

Chris Cornell and Kim Thayil dissect Soundgarden's masterpiece, Superunknown

In this classic 2014 interview, Cornell and Thayil break down the tones, tunings and ambition behind the album that made Soundgarden one of alternative rock's biggest bands

This feature first appeared in the August 2014 issue of Guitar World.

During the summer of 1993, Soundgarden were holed up at Bad Animals Studio in Seattle, Washington, working on the follow-up to their semi-successful third album, 1991’s Badmotorfinger.

Guitar World’s intrepid Seattle correspondent, Jeff Gilbert, was on hand to get the scoop on the hotly anticipated new record. During his interview, he talked to guitarists Kim Thayil and Chris Cornell about the fact that Nirvana, Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam – three of their Seattle brethren that formed well after Soundgarden – had achieved mass commercial success with their albums, while Soundgarden were still waiting for their breakthrough.

“I’ll admit that sometimes I ask, ‘Why them and not us?’” Thayil told Gilbert. “But I feel splendid being in the shadow of Nirvana and Pearl Jam. It’s almost like someone is firing ray guns and these guys have provided a dome shelter over us, taking all the heat.”

“When Mother Love Bone got all this attention and played music that connected with people a lot quicker and was easier to take than Soundgarden music, it took a lot of focus off us, which was great,” added Cornell.

“It was the ‘big fish in a small pond’ thing, which I’m not into at all. It’s too hard to hide when you’re the big fish. I’d rather be a miniscule brine shrimp in a polluted ocean, which is more fun to me.”

It’s safe to say that Cornell’s “fun” ended just a few months later, when Soundgarden’s fourth studio album, Superunknown – which is currently celebrating its 20th anniversary with a super-deluxe reissue package – came out and shot straight to Number One. In the process, it catapulted Soundgarden into the upper echelon of rock stardom they had somehow managed to avoid since their formation a decade earlier.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“A lot of it was just timing,” Cornell says today. “Everything was changing at the time– radio was evolving and the perspective of the listening audience was changing. The age of the audience too – a new generation was maturing and was ready for a band like us. So I think it was the perfect time for that record.”

“With Superunknown, it was already a few years after the meteoric rise of bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam,” Thayil adds, “and we knew that this was our fourth album and that we had already been touring and making records for quite a long time, even before Nirvana and Pearl Jam were bands.

“So when Superunknown came out and became successful, we kind of felt that it was the fruits of our labor. I don’t know if we felt we deserved it, but we had definitely earned it by that point.”

Listening back to Superunknown, it’s easy to understand why it resonated so profoundly with the commercial rock audience: in short, it had everything.

A sprawling, ambitious piece of work comprising 15 songs and clocking in at more than 70 minutes, Superunknown was the mark of a band that had reached creative maturity, with songs that ranged from shimmery, morose dirges (Black Hole Sun, The Day I Tried to Live) to psychedelic Beatles-inspired strummers (Head Down) to quirky, Middle Eastern–flavored ditties (Half) and pummeling, detuned sludgefests (Mailman).

Superunknown may have taken only a few months during the summer of 1993 to write and record, but it’s clearly an album 10 years in the making – the culmination of Soundgarden’s evolution from young, aggro-grunge pioneers to experienced musicians capable of producing a masterwork.

When I listen to that record, I don’t often see or hear opportunities for me to have improved anything. And it’s a tough thing to not do that

Kim Thayil

“With the whole Superunknown process, everyone felt pretty confident that it was a really strong, great record,” Thayil says. “We felt that way with Badmotorfinger, too – and there was probably a little bit more hesitation with [1996’s] Down on the Upside and even [1989’s] Louder Than Love. There was very little second-guessing with Superunknown.”

People often cite Superunknown as Soundgarden’s masterpiece. Do you agree?

Kim Thayil: “You know, if I look at songs, I like so many songs that were on other albums, perhaps even more than the ones on Superunknown. But if you look at the album as a collection of songs, it’s very strong. The production was great, the performances were pretty damn great, and the mixing was really good.

“When I listen to that record, I don’t often see or hear opportunities for me to have improved anything. And it’s a tough thing to not do that, to not see where things could be improved, especially because we’re a very critical and self-conscious band.

“I’ll go back and listen to Louder Than Love and think that a certain riff was so cool live, but that I didn’t get the same balls out of my performance in the studio. Maybe I seem a little too reserved, and if I could go back and do it again I’d make the riff grind a little more. Or you listen to the mix of an album and you think, ‘Oh, this part’s too loud,’ or, ‘This part isn’t really coming through.’ But with Superunknown, I really don’t hear a lot of that.”

Chris Cornell: “There are a lot of people who discovered Soundgarden around the time of Badmotorfinger, and to them that’s the definitive Soundgarden album. Superunknown is something else to them, where we got more eclectic and less aggressive. That album was less of an onslaught of aggressive rock from beginning to end.”

The record came out in March 1994 and was an immediate sensation, debuting at Number One on the Billboard charts. How did the band react to the news of being Number One?

Thayil: “We were in England, and we were getting into an elevator in our hotel when our manager, Susan Silver, told us that the upcoming issue of Billboard magazine was going to list us as Number One. And we knew it was a big deal and we were excited about it, but we weren’t jumping up and down about it either. We thought the record would do well, but coming in at Number One was a surprise.”

What’s your take on why Superunknown was so successful so quickly?

With Superunknown, we were a band that was in need of reinvention by then

Chris Cornell

Cornell: “There’s something to be said for what was happening to the band around the time that Superunknown was written and recorded. In a sense, Badmotorfinger was a definitive album in terms of the super-aggressive part of Soundgarden – the part that was developing over time. And we didn’t start out that way, but we became that with Badmotorfinger.

“I do think you could have swapped [1996’s] Down on the Upside with Superunknown, and I think it would have gotten a similar response. In many ways, Down on the Upside and [2012’s] King Animal are closer to what we wanted Superunknown to sound like.

“With Superunknown, we were a band that was in need of reinvention by then. We had already been a band since 1984, so when Badmotorfinger came out and sold so many records and people were starting to hear about it, we were already at a point creatively where we needed to move, and we did with Superunknown. It was actually a mature part of our lifespan as a band, even though people were just hearing about us for the first time.”

Commercial success never really seemed to be a primary goal for Soundgarden, or any of the Seattle bands for that matter. Was the success of Superunknown difficult to handle?

Thayil: “Not exactly, but it did take a little bit of effort for us to wrap our heads around it. I think we had an appropriate distance from it so that we could stay well humored about the whole thing.

“We didn’t take it too seriously, but we certainly held it in regard, if that makes sense. Because it was never an objective of ours, we didn’t attach a lot of weight to it. I think that if you get too emotionally attached to things like that, it just makes it harder to deal with when it eventually goes away.

“For us, we were always more excited about things like songwriting and recording – hearing a song transform, even looking at the grooves on the record when you first get it. That always seemed tangible and real to me. It was what I could identify with my listening experience growing up. Like getting Kiss Alive! and look- ing at the grooves on the record and going, ‘Okay, song two there is Strutter.’

I don’t think we shouldered as much resentment against us as perhaps Nirvana or Pearl Jam. Those bands became huge and successful so quickly

Kim Thayil

“So that kind of stuff was a big deal to us – writing songs that were satisfying to us or having a little cassette of the music in anticipation of it coming out on vinyl. Everything else – the accolades, the awards – we held in regard but didn’t marry our- selves to that aspect of our work.”

Does all the attention become too much?

Thayil: “Not the success of the record or the accolades, because like I said, we kind of kept that at arm’s length. But what would have been too much is the constant pushing and touring and interviews and in-store appearances.

“I remember when we were touring for Louder Than Love, we were doing, like, two or three in-stores a week, and that always seemed awkward. Sitting there signing posters and record flats just didn’t seem like part of the whole music experience. And when you become as successful as we did with Superunknown, things happen so quickly and everyone wants a piece of you – the record company, the radio stations, the press all want your time.

“But that’s not as bad as the family that expands when you become successful – the friends, the casual acquaintances, the people at the store or the gas station. That can be difficult to predict and manage.”

What was it like to have come up with so many bands in the Seattle scene and become hugely successful while many of your friends didn’t?

Thayil: “That stuff can get a little weird, but I don’t think we shouldered as much resentment against us as perhaps Nirvana or Pearl Jam. Those bands became huge and successful so quickly. At one point Nirvana was in Europe opening for Mudhoney and Tad, and the next thing you know they just eclipsed everybody.

“There was definitely some kind of hierarchy – like a commercial segregation – of bands who were all peers back then. At one point we’re all in the same boat and we’re peers, and the next thing you know you’re playing different venues and dealing with a different level of success than the other bands. And none of that bothered us personally because we had the properly proportioned success that you’d expect based on the time and the work that we had put in during our career. It totally made sense for us.

“But when I think about the work that bands like Tad and Mudhoney and Screaming Trees put into it, it would have been good for them to have some success, too. And their producers too, guys like Jack Endino and Steve Fisk, who worked on so many of these records and watched as the bands got bigger and went on to some other label and some other producer.

We had the properly proportioned success that you’d expect based on the time and the work that we had put in during our career. It totally made sense for us

Kim Thayil

“So there definitely was a strong sense of community in Seattle back then, and you kind of got this sense that some people perhaps felt left behind or not included, and that’s where you experience some bitterness or resentment when you become successful. And some of those people were actually fairly well aware of that attitude that was festering within them, and over a few beers they were able to address that sense of bitterness that they had, and they knew that they were the only ones accountable for having those feelings.

“Other people were less forward or adjusted in their understanding and just behaved in a jilted fashion. And then you had those people who were just happy for you – at least on the surface.”

Was there a sense of obligation to give back to the Seattle bands who didn’t achieve the same level of success as Soundgarden?

Thayil: “We definitely did that. We brought some of those bands out on the road with us, that kind of thing. And I don’t know if it was obligation as much it was that we loved those guys and wanted to help them out and give them every opportunity.

“When we were all coming up and playing together, we were all very supportive of each other. We were never competitive with each other. You used to hear these crazy stories about New York and Chicago and how you had these different hardcore camps, and how you could only be friends with these guys over here but not those guys over there.

“And Seattle was never like that. For the most part, everyone was very supportive of each other, going to see each other’s bands, providing opportunities and opening doors for each other.”

Getting back to Superunknown, at any point did the band members get together and discuss what kind of record you wanted it to be, or did it just evolve naturally?

Thayil: “No, we never did. That kind of a thing might work if you’re the kind of band that has one primary songwriter, like Nirvana or Smashing Pumpkins. As the solitary author, you can have that vision and say, ‘I want to try this,’ and the band either sinks or rises with that particular vision.

“With Soundgarden, you basically have four crap detectors – four guys who have to enjoy the song and the material and enjoy playing it. It would be hard for us to ever make a crappy record, because you would have to have four guys miss the boat at the same time. We just have too many songwriters and too many critics, and we’re our own audience.”

There were songs still being written during the recording process, so we were always tracking and learning new songs while we were working on other ones

Chris Cornell

Chris Cornell: “The truth is, I really didn’t know what the record was going to be until we were mixing it with Brendan O’Brien. It wasn’t until I had eight or so songs that were mixed and listenable that I knew how great the album was going to be and how different it was going to be from anything else we had done before it.

“There were songs still being written during the recording process, so we were always tracking and learning new songs while we were working on other ones. That process allowed us to experiment in the studio and tap more into that Pink Floyd side of the band. We were adding different things in different layers, and one of the things about Soundgarden is that everyone in the band is allowed to do that.”

Kim, when did you realize that Superunknown was something special?

Thayil: “We kind of look at it song by song, so when you get a demo of a song like Black Hole Sun, you think, ‘Oh my god... this melody is really catchy.’

“Initially with that song, I felt that it didn’t really play to my strengths as a guitarist who was weaned on punk rock and metal. I mean, it might not be what I want to play, but I knew that it was a really strong song and that longer to catch on, and some catch on quicker but then you outgrow them.

“So we get a sense of the strength of individual songs, and when you put them all together it lets us see how the record is shaping up.”

Looking at the songwriting credits, it seems as though you had more contributions on Superunknown – My Wave, Superunknown, Limo Wreck, Kickstand – than on previous records.

Thayil: “It was certainly more than on the subsequent record, Down on the Upside, but I don’t think it was any more than on the previous records. The truth is, my contributions are on every song.

“The way we credit songwriting, we look at a song linearly – who came up with the verse, who came up with the chorus, that kind of thing. But there’s a lot of vertical composition when it comes to songwriting, especially with guitars and vocals. You’re coming up with melodies and countermelodies, little color parts – feedback or harmonics, things to flesh out a song and give it some depth. So that stuff is always there whether it’s credited or not.

Chris used to write maybe a skeleton of a song, and then we’d kind of put the flesh on it. But with Superunknown and a song like Black Hole Sun, Chris did that all himself, everything but the guitar solo

Kim Thayil

“Certainly in the early days of the band, I did the majority of the writing, at least the guitar writing and the music, while Chris did the majority of the lyrics. But that changed over time, because Chris became quite prolific around the time of Temple of the Dog [Cornell’s 1991 side project] and Badmotorfinger. He started taking bigger risks with his songwriting, and he learned how to manage his time, and he dedicated that time to songwriting. He used to write maybe a skeleton of a song, and then we’d kind of put the flesh on it. But with Superunknown and a song like Black Hole Sun, Chris did that all himself, everything but the guitar solo.

“Everyone in the band is creative and wants to feel the contribution, but it varies from song to song, and that’s the way we’ve always worked. Not everything you do gives you a songwriting credit, and there’s a lot more contribution from the band members than what is credited.”

That doesn’t seem entirely fair – contributing to the songwriting without being credited.

Thayil: “It’s just something that varies from band to band. Some bands give credit to everyone in the band for every song. But in some of those bands, I can’t imagine that the drummer is contributing as much as the guitarist.

“On our first album, Screaming Life, we said that all songs were written by Soundgarden, even though most of the music was written by me and most of the lyrics written by Chris, and there was one song where the lyrics were written by [bassist] Hiro [Yamamoto] and another song where the music was written by Chris. After that, we decided to credit things by who brought in the idea or who came up with the other parts – the verse or the bridge or the big riff.

“That’s just how Soundgarden does it. And you can never be fully satisfied. I mean, would you be happy if you’re the primary guitarist and songwriter and sharing credit with the bass player and drummer, who didn’t contribute as much?”

Does having Chris as the primary songwriter in the band take some pressure off you to write?

Thayil: “No, I don’t see it that way at all, because everyone likes writing songs. I certainly enjoy coming up with riffs and writing songs more than just playing guitar. It’s really easy for me to come up with riffs. Where it becomes a struggle is in organizing everything. But that struggle could easily be overcome by spending an hour or two every day working at it, but that’s just not my style. Then it becomes drudgery.”

For the recording of Superunknown, you went with Michael Beinhorn as producer rather than Terry Date, who produced the two previous records, Badmotorfinger and Louder Than Love. Why the switch?

Cornell: “We just felt it was time to give somebody else a try. I think we wanted a little bit more of a looseness with Superunknown, in terms of the production. I think Terry was really good at what he got on Badmotorfinger, that aggressive, heavy guitar-rock sound. But there was more of a post-punk indie aspect to what we actually sounded like in a room, and he would shy away from that.

Every producer we ever used essentially ended up being kind of an engineer. We didn’t really use producers in the classic sense of listening to their ideas because we didn’t really need them

Chris Cornell

“He didn’t want vocals to be distorted, and he wanted drums to sound kind of hi-fi rather than lo-fi. All of the things that we were used to and that we liked and that we would sometimes ask for, he would get nervous about. I think he made great-sounding records, but we just wanted to color outside the lines a little more with Superunknown.”

Did you achieve that with Michael?

Cornell: “In some ways, maybe. He introduced the idea to me of doing my vocal takes alone – just being the only one there and doing the engineering myself. It was something that always worked for me when I was at home doing demos, so it made sense to try it in the studio. I remember with Black Hole Sun, Michael had me sing it, like, 11 or 12 times, and then he made a comp of the lead vocals, and I hated it. After that I just started doing all my vocals alone.

“The truth is, every producer we ever used essentially ended up being kind of an engineer. We didn’t really use producers in the classic sense of listening to their ideas because we didn’t really need them. We used them because it was a way of keeping the record companies from getting nervous – because they knew that there was somebody else in the sessions with us.

“But for us, using a producer was about finding ways to record our ideas and flesh them out better, and get on tape what we wanted to hear. Unfortunately, producers never really worked for us. They were never very helpful.”

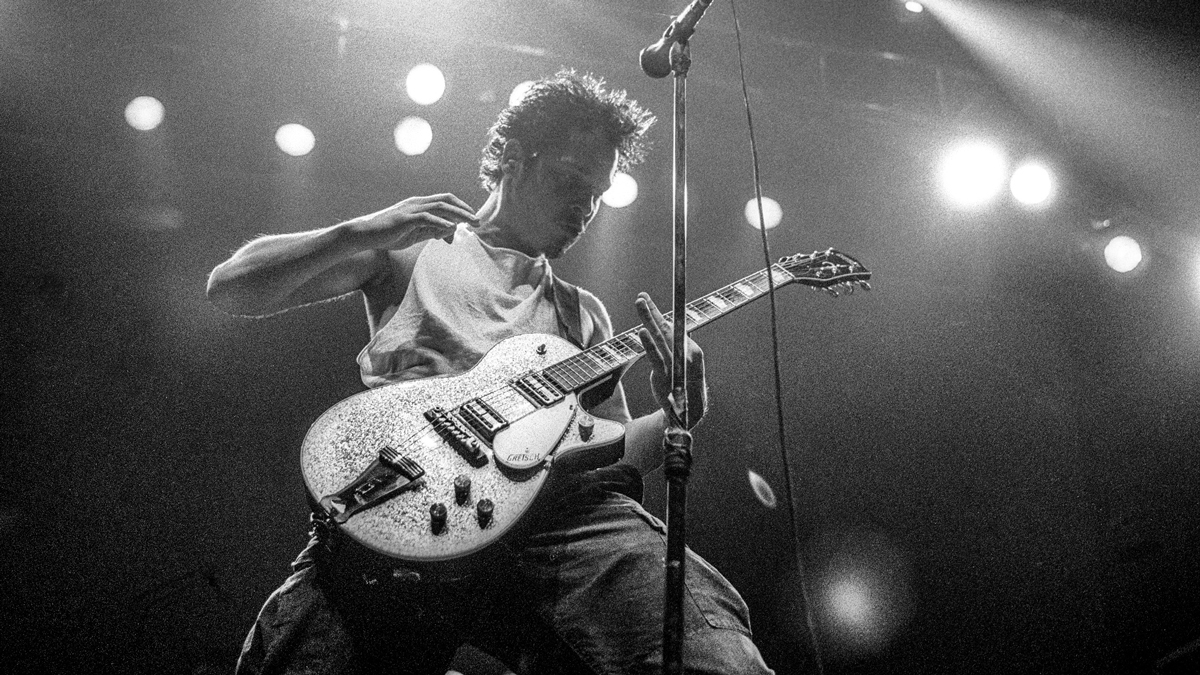

The guitar sound on Superunknown is just massive. What was the secret to getting that?

Thayil: “The first thing I would look at are the tunings. We used a lot of different tunings on Superunknown, and a lot of them are dropping the E string, dropping the A string or dropping all the strings. And that gave a real heaviness to the sound, both in pitch and because the strings are a little looser and resonating differently. You certainly hear that on the riff to Limo Wreck.

My guitars have a little bit more low end, so you get that massiveness, and Chris – probably because he was originally a drummer – likes that crispness, that brightness that you get with a snare or hi-hat

Kim Thayil

“Then you have the combination of my guitars and Chris’ guitars. Mine have a little bit more low end, so you get that massiveness, and Chris – probably because he was originally a drummer – likes that crispness, that brightness that you get with a snare or hi-hat.

“There was also a period of time before Superunknown where I would always scoop the mids out of my sound. I just like the low sound or the bright sound, and the mids to me just made everything sound like a Les Paul and a Marshall stack – like every other hard-rock guitar.

“So by the time of Superunknown, those mids were being filled in by Chris, which meant that you had both guitars in there. So I think between that and doubling up the guitars and the tunings, that’s how we got that sound on Superunknown.”

The new Superunknown 20th anniversary reissue package contains a lot of extras – demos, alternate takes and various rarities. Was it fun to go back and rediscover all that material?

Thayil: “There were definitely some pleasant surprises and some serendipitous surprises. You’re going through some things looking for one thing and something else turns up, and you’re like, ‘Oh, I haven’t heard this in, like, 20 years.’

“We uncovered all kinds of things – alternate interpretations of songs, live versions of songs that never made it to a record, demo versions where you could see how a song evolved – and some of it you would recognize and some you wouldn’t. So that was all very rewarding.

“The reissue has a lot of that material on it, but we didn’t use everything we uncovered. Sometimes there’s a reason why you don’t want to put something out. Maybe the performances were less than stellar, or it was a work in progress. And you want to show some of the works in progress, but not all of them. Some things you want to keep just for yourself.”

As a teenager, Jeff Kitts began his career in the mid ’80s as editor of an underground heavy metal fanzine in the bedroom of his parents’ house. From there he went on to write for countless rock and metal magazines around the world – including Circus, Hit Parader, Metal Maniacs, Rock Power and others – and in 1992 began working as an assistant editor at Guitar World. During his 27 years at Guitar World, Jeff served in multiple editorial capacities, including managing editor and executive editor before finally departing as editorial director in 2018. Jeff has authored several books and continues to write for Guitar World and other publications and teaches English full time in New Jersey. His first (and still favorite) guitar was a black Ibanez RG550.