Charting the evolution of solid-state and digital guitar amps – and the future of tubes

Non-tube amplification is nothing new. While the future for tube amps is far from certain, innovation in digital and solid-state designs is something to be excited about

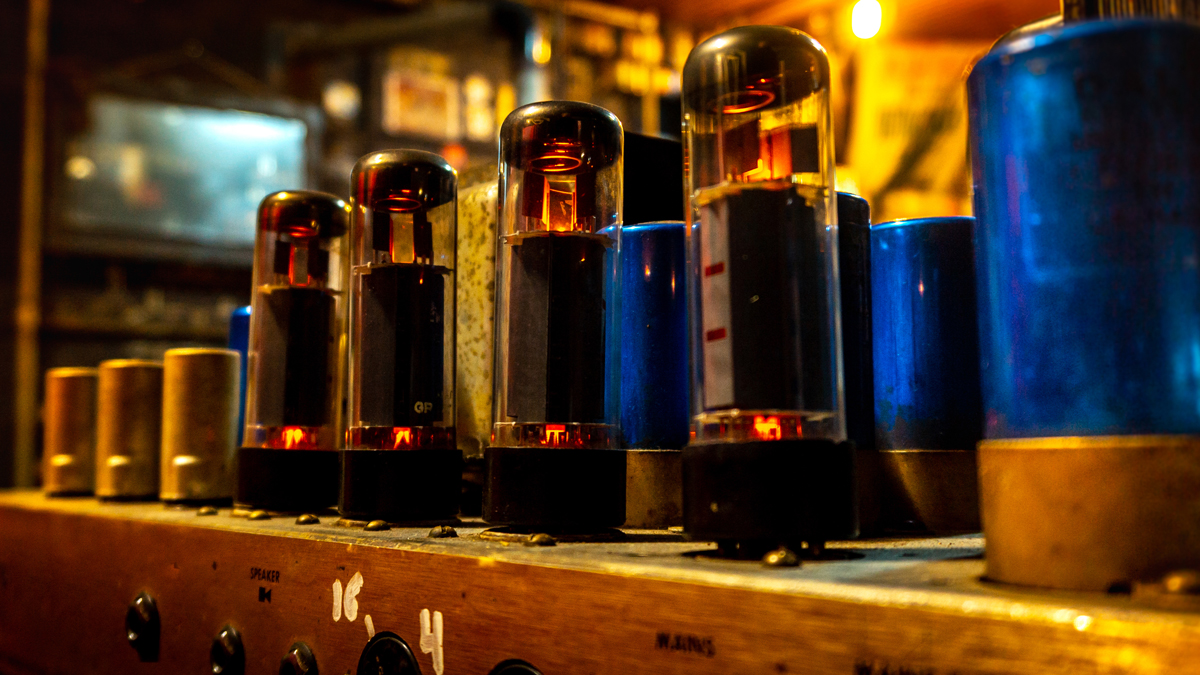

Wars typically speed up developments in technology, and one goal throughout WWII was to find a replacement for the bulky, energy-hungry, fragile glass electron valve, more commonly known as the vacuum tube.

The first working transistor was demonstrated by Bell Telephone Labs in 1947 and publicly announced in June 1948. Initially available only to the military, the first domestic products were hearing aids.

The arrival of the first transistor radio – the Regency TR-1 in 1954 – was viewed as a novelty, but its small size and portability was a sign of things to come. Over 100,000 TR1s were sold in its first year, but Sony’s smaller and cheaper TR-63, introduced to the US in 1957, ended up selling in the millions.

It was the success of these radios that led to transistors replacing valves as the dominant technology. Almost overnight, as transistor mass production ramped up, valve production disappeared.

Several pioneering manufacturers produced transistor-powered guitar amps from the early 1960s. One of the earliest, wackiest and rarest was surely Höfner’s Fledermaus or ‘Bat’ Guitar, which had a built-in transistor amplifier and speaker based on an early radio.

Possibly scoring a double as the first guitar with active electronics, it’s thought no more than a dozen were made. Other early UK examples included Vox’s T60 bass amplifier, dating to around 1962 and used by Paul McCartney among others, while Fender introduced transistor versions of some amplifiers in 1966.

Early transistor amplifiers had a poor reputation for reliability. However, a new innovator from America would consign solid-state power and reliability issues to the past. In 1965, Hartley Peavey established the Peavey Electronics Corporation in Meridian, Mississippi, hand-building his first amps – the Musician and Dyna-Bass.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While Peavey is also well-known for tube designs, its chief strength has always been solid-state, with the expertise gained from building reliable high-power PA amplification filtering back into guitar products.

By the early 1970s, transistors were more reliable and the MOSFET (Metal Oxide Semiconducting Field Effect Transistor) became the main workhorse for many PA and guitar amps.

These transistors powered products such as WEM’s Dominator 100 and Carlsbro’s popular Stingray series, alongside designs from most major manufacturers, including Fender, Vox, Marshall, Yamaha, Roland and Music Man, who had significant success with their hybrid approach, combining solid-state preamps with valve power stages.

Another hybrid amp that threatened to make a big impression was Roland’s Bolt 60, but it was its mighty Jazz Chorus 120 stereo combo from 1975 that broke the Fender Twin Reverb’s dominance for big stage clean sounds.

With built-in stereo chorus and indestructible build quality, the JC-120 quickly became a standard addition to festival and tour-equipment riders, and has been there ever since. For many musicians and industry watchers, the Jazz Chorus marked the moment solid-state guitar amplification properly arrived.

Meanwhile there was a digital revolution happening in audio production driven by the arrival of the desktop PC, as 24-track magnetic tape recorders were replaced by computer programs and special audio interface cards.

For many, Roland’s JC-120 marked the moment solid-state guitar amplification properly arrived

Tracks could be cut, copied and pasted with a few mouse clicks and previously impossible digital effects could be added. Digital reverb replaced springs, plates and chambers in many studios, while sample-based synthesizers, such as the Synclavier, threatened to replace real instruments.

This was the era of the guitar-rack system, as pro guitarists took rack-mounted effects out of the studio and on to the stage in order to replicate their recorded tones.

While most digital effects had a MIDI interface, most guitar amps didn’t, so hooking everything together and controlling it from a convenient footswitch was new territory, pioneered by industry legends Paul Rivera and Bob Bradshaw in the US, and Pete Cornish in the UK.

Programmable guitar preamps weren’t far off, though, and while several manufacturers built matching stereo valve power amps, their size and weight made solid-state a more compelling choice.

An early sign of things to come was PA:CE’s impressively expensive and heavy Redmere Soloist introduced in 1979, with three analogue solid-state channels emulating Fender, Marshall and Vox amp sounds. The arrival of Line 6’s AxSys digital modelling amplifier in 1996 was followed by the POD, using digital signal processing to emulate different well-known amplifier brands and effects.

Two decades on from Line 6’s revolutionary red bean-shaped gadget, digital modelling is now a firmly established technology, both as software and hardware, with most amp manufacturers having at least one digital range in their catalogue.

As processing power improves, so has the realism of digital amplifier models. Combined with the more recent innovation of Class D power amplifiers, which deliver valve-like dynamics from high-powered small and lightweight packages, it’s looking increasingly like digital amp-modelling is ready to take over. And not before time.

Expiration Date

Today, the future for tubes is somewhat uncertain, but we should say, somewhat optimistically, that as long as there’s a market it will be supplied.

However, it’s possible the 2020s could be the last decade of vacuum tube mass-production – particularly given recent export issues with Russian tubes – which would affect bigger amp producers without viable non-valve alternatives. Smaller boutique builders should be able to carry on, though, and you’ll still be able to buy replacements for your favourite tube amp for many years.

Truly spectacular offerings from several mainstream manufacturers in recent years have closed the gap to the point where even the die-hard tube supporters are beginning to admit there’s no longer any difference

The outlook for non-tube guitar amplifiers, then, looks increasingly exciting, whether you choose analog solid-state or digital. Truly spectacular offerings from several mainstream manufacturers in recent years have closed the gap to the point where even the die-hard tube supporters are beginning to admit there’s no longer any difference. Given the choice, which would you go for?

Keeping tube amps sounding at their best, especially older and vintage models, often turns into a war of attrition that’s likely to become more expensive as valve prices go up. If you compare a 60-year-old heavy, unreliable valve combo with a modern digital equivalent that looks identical, sounds consistently great night after night with practically zero maintenance, weighs half as much and costs half the price, what’s not to like? We think the future’s already here. Bring it on!

Nick Guppy was Guitarist magazine's amp guru for over 20 years. He built his first valve amplifier at the age of 12 and bought, sold and restored many more, with a particular interest in Vox, Selmer, Orange and tweed-era Fenders, alongside Riveras and Mark Series Boogies. When wielding a guitar instead of soldering iron, he enjoyed a diverse musical career playing all over the UK, including occasional stints with theatre groups, orchestras and big bands as well as power trios and tributes. He passed away suddenly in April 2024, leaving a legacy of amplifier wisdom behind him.

“If you’ve ever wondered what unobtanium looks like in amp form, this is it”: Played and revered by Stevie Ray Vaughan, Carlos Santana, and John Mayer, Dumble amps have an almost mythical reputation. But what's all the fuss really about?

“For the price, it’s pretty much unbeatable”: Harley Benton JAMster Guitar review