“I had a Gibson deal at one point where I could get Les Pauls at factory prices. I would sell them at pawn shops and put the money towards older Les Pauls”: Mike Ness on fighting cancer and the roots influences behind Social Distortion’s self-titled LP

Ness and co hit us all with a curve ball as the ’90s dawned, covering Johnny Cash’s Ring of Fire and bringing blues into punk, but as Ness explains here, it's all related – it’s all punk

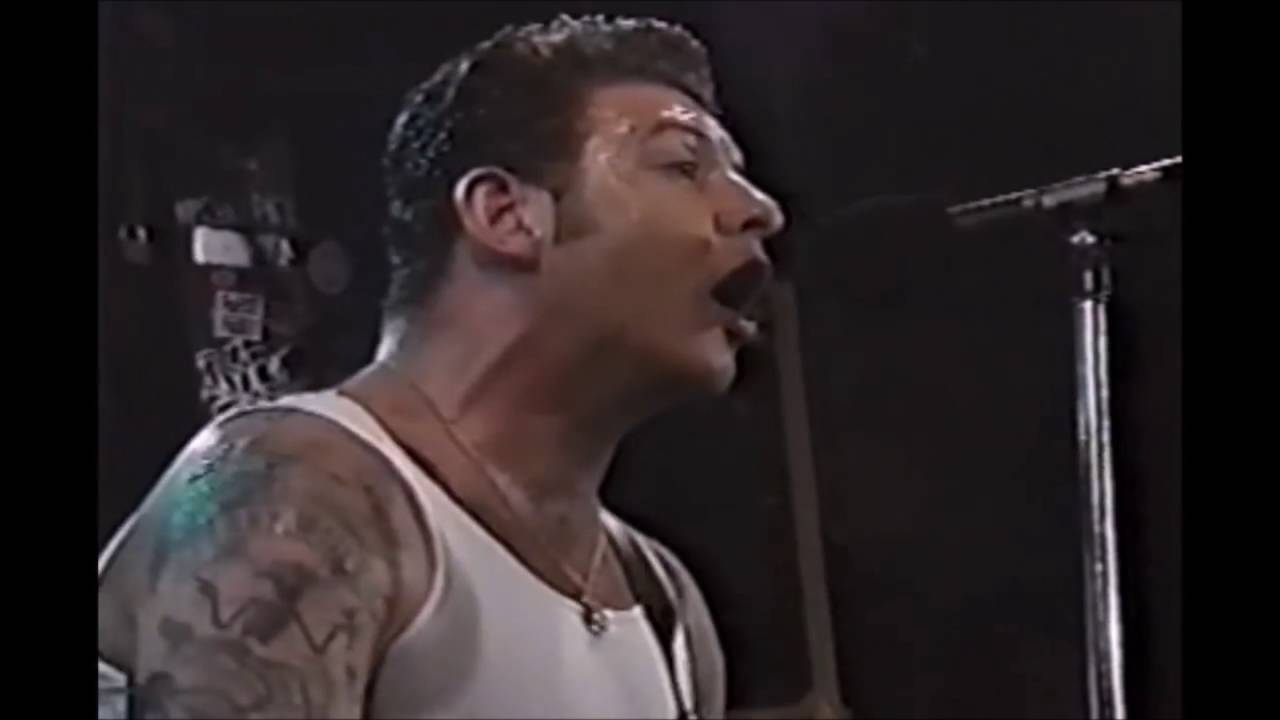

Social Distortion formed in 1978, and amid ever-changing lineups, the presence of singer/guitarist Mike Ness has been a constant. With the release of their self-financed debut album, Mommy’s Little Monster, in 1983, they rapidly became one of the biggest names on the California punk scene, influencing countless bands in their wake.

Ness’s well-documented addiction problems then saw the band stall, with a five-year gap between their debut record and its 1988 follow-up, Prison Bound. Ness knew he had to prioritize his recovery over the band’s progress at that time. “There wouldn’t have been a band if I didn’t sort myself out,” he says.

Social Distortion continued to play regularly, maintaining their hardcore, loyal fan base even when they were dormant on the recording front. Those followers were initially taken by surprise with the release of Prison Bound, which saw Ness draw heavily on the rootsy American genres of blues, rock ’n’ roll, country and rockabilly to deliver a record that was considerably different from the straightforward punk of their debut.

Two years later, the band signed to Epic, giving Ness some much appreciated financial security. “I was able to give up my day job as a house painter and focus on music,” he says. With the machinery of a major label behind them, the band’s third album, simply titled Social Distortion (1990), saw them achieve their best sales to date and established them as major-league players.

The record firmly defined the Social Distortion blueprint for every album that followed, with Ness utilizing the soulful roots of Americana harnessed to the raw energy of punk, as the ultimate means of expressing his unique musical mojo.

Ness has been out of action for more than a year since receiving a diagnosis of tonsil cancer at the end of 2022; but he has come a long way down the road to recovery, scheduling live dates for Social Distortion this spring.

How’s your health?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I’m doing a lot better, continuing to make progress and working hard on my rehab, but it’s been a tough time. It’s been almost a year now. Head and neck cancers are a lot different from other cancers; it’s not an easy surgery. I’ve had to go through intensive rehab just for speech and swallowing, let alone singing. I feel like I still have a lot of purpose in this world, so we’ll see how things go.”

I was halfway through recording the next album when I got cancer, so that’s had to go on hold while I’ve been working on getting better

When the self-titled album came out in 1990, it was quite a departure from 1983’s Mommy’s Little Monster, although Prison Bound probably eased the transition. Were you worried about alienating that hardcore bunch of original fans?

“At that time, I was really getting back in touch with a lot of the music I grew up with, which was American roots music. I saw all these other bands bringing those influences to their music and I thought there was no reason I shouldn’t. A lot of punk, British and American, had an acknowledgement of ’50s music, even if it was in the way that bands dressed.

“Even the Sex Pistols’ album has Steve Jones playing Chuck Berry licks all over the place. In the mid-’80s a lot of bands started to sound the same; if you wanted to stand out, you needed to do something different. For me, it was bringing that American roots music into the sound. Why can’t you do both?”

The cover of Johnny Cash’s Ring of Fire seemed to be a defiant nailing of your colors to the mast of Americana.

“That’s absolutely the case. I got a lot of flak from my peers about it, asking why I was going to do that, and I said it’s because I thought it was cool. [Laughs] I remember thinking, 'I don’t need to check in with anyone else about what I want to do in my band,' you know? People were telling me I couldn’t do that, and I was saying, ‘Whose fucking band is this?’ [Laughs]

“The release of the self-titled album was definitely a defining time for what I wanted to do and say musically. I didn’t know if people would like things like Sick Boys and Story of My Life, but I thought there was a similarity to some of the songs on Prison Bound. I guess I write ballads in the old-time sense of that word – songs that tell a story.”

Did you have any sense that – with the subsequent change in direction – you could alienate fans of the first album?

“There’s always that risk, but I’ve learned that you don’t get anywhere if you don’t take a risk. The true spirit of punk is to evolve. You want to maintain the primitive spirit, but the important things in punk for me were honesty, energy and attitude, so as long as I didn’t lose those things, I felt safe.”

Was there much in the way of pre-production ahead of the recording sessions with producer Dave Jerden?

“Not really in a rehearsal room or whatever. I did give Dave a tape with the songs we were going to record, but he seemed happy with everything we planned to do. He always made things very comfortable for me, letting me go with how I felt things should be, while he took care of the technical side of things. That was one way of working, which I enjoyed.

“Michael Beinhorn produced White Light, White Heat, White Trash in 1992. He took a very different approach. I came in with 12 songs, played them to him and he told me to keep writing. [Laughs] Initially, I thought, What the fuck? [Laughs] That was a good thing in its own way as it pushed me to come up with some of my best songs.”

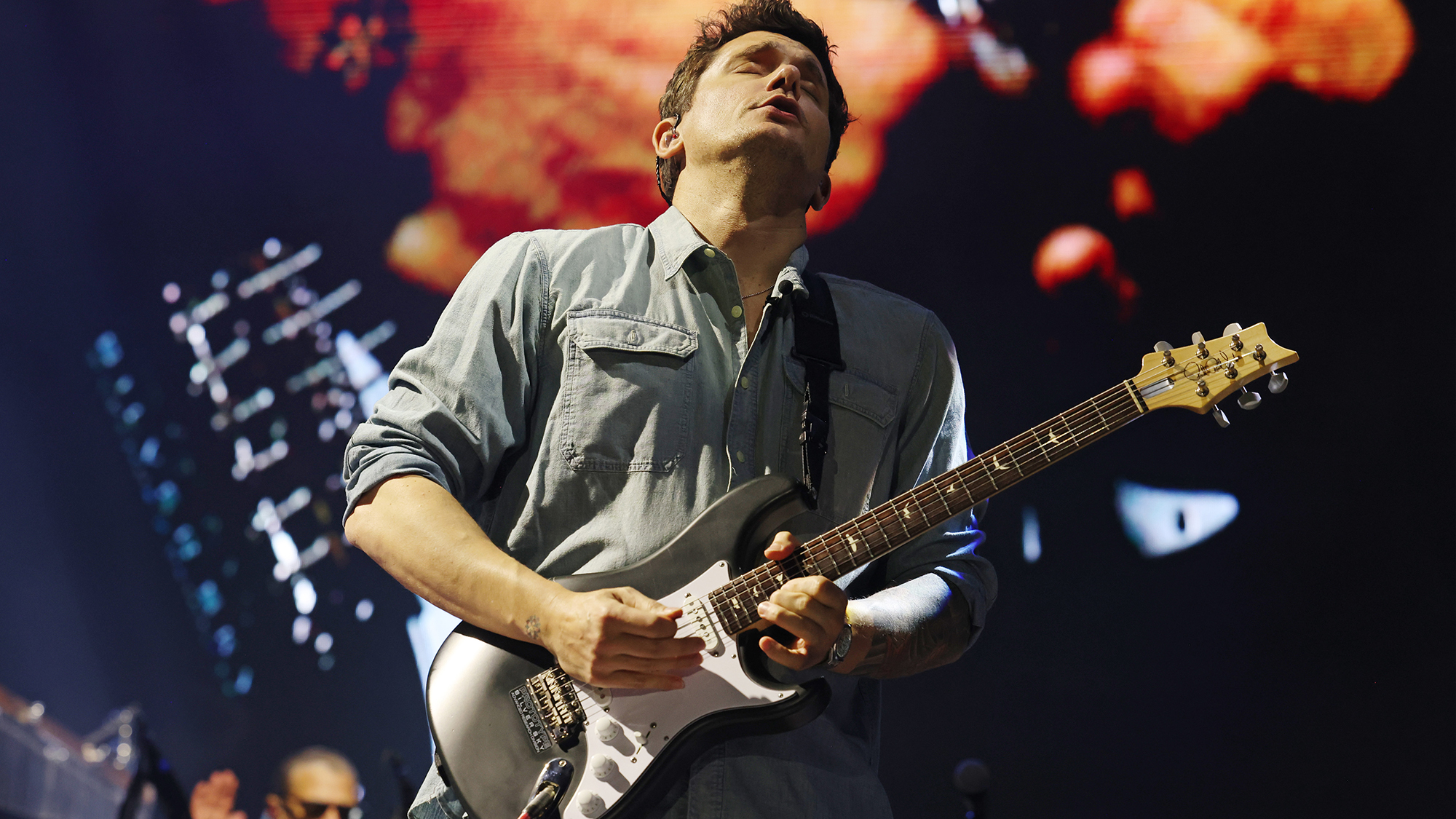

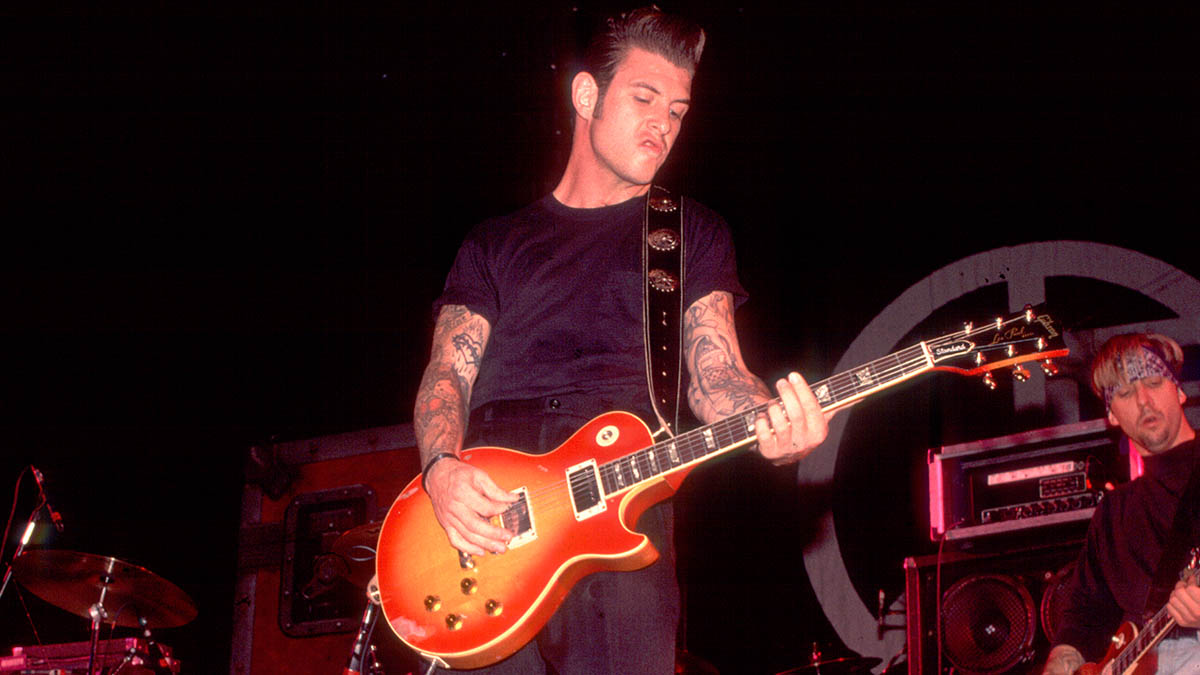

What were the primary guitars and amps that you used?

“I think I was definitely using Les Pauls, but not with P-90s; that came after I toured with Neil Young and learned about tones from watching what he was doing. For amps it would have been Marshalls and Fender combos in various configurations. Dennis [Danell], who played rhythm guitar, was playing old Les Paul Juniors. He always had a knack for finding great old gear.”

The influence of Kiss was massive; they had a huge impact on me, as much as the Stones and the Ramones. I don’t think Kiss get their due credit

Let It Be Me seems to be channeling Johnny Thunders and Ace Frehley.

“Those are two of my favorite guitarists. To me, early Kiss was better than the New York Dolls. They were both playing a similar kind of blues-based rock ’n’ roll, but Johnny Thunders was always a big influence for me. The influence of Kiss was massive; they had a huge impact on me, as much as the Stones and the Ramones. I don’t think Kiss get their due credit.”

Ball and Chain almost connects the dots between the Clash and Bruce Springsteen.

“Yeah, I get that. It’s kinda like a ballad again, but in fact maybe it’s more like a prayer. [Laughs] I injured my left hand when I was 18, and because of that, I had to pick chords differently, and that impacted the way I’d play blues scales a lot. I think that fed into the way that a lot of my solos became more thematic in terms of stating melodies rather than wailing on scales.

“I was able to take a bad situation with my hand and make it into a good one by adapting what I played. I think that approach informs the sense of scale on this song. The Buzzcocks were another factor in that melodic approach for me. I always really liked the way that the solos on their records would be a re-stating of the melody from the song.”

Drug Train is the last track on the album, and it appropriately moves the band furthest into straightforward bluesy rock ’n’ roll.

“Yeah, this states clearly that we’re going to do what we want, without the conventions of punk or anything. When you listen to real, old blues, it doesn’t get more punk. The honesty and emotion of that music are a real good fit for me.”

What got you into playing?

“Listening to the radio when I was about five or six. Everything I was hearing was taking me on a journey in my mind and firing up the urge to want to try to play music.”

What’s your guitar-buying history?

“At first, I had a couple of $40 Japanese electrics that weren’t much good. My first decent guitar was an early ’70s SG that I’d saved up for. When I started to make some money from the band, my first big purchase would have been when I got my first ’79 Goldtop Deluxe.

“I had a deal with Gibson at one point where I could get Les Pauls at factory prices. What I’d do, when I was on the road, was take them into pawn shops and sell them and use the money to put toward older Les Pauls.”

Do you use your signature guitars?

“I don’t, although they are really great guitars. I think there’s a certain vibe about my original – the one the signature model is modeled on – that I can’t find in another guitar. It just doesn’t have the road years under its belt. It’s just that old pair of shoes that’s a perfect fit.”

It’s ironic that they cost more than twice as much as an actual 1979 goldtop Les Paul Custom.

I was halfway through recording the next album when I got cancer, so that’s had to go on hold while I’ve been working on getting better

“It is kinda weird. I never realized they’d be so expensive when they suggested that they’d make a signature model. I’m working on an idea with them to see if they can do some kind of more affordable signature model that would be a lot more accessible.”

How do you feel about the album more than 30 years later?

“If I ever hear tracks from it, I’m always happy with the way they turned out. I’m not one of those people who listens back and wishes I’d done everything differently. I don’t listen to my own music very often, but it is good to listen to your old stuff every now and then. It’s good to connect with the spirit that I was capturing back then. Sometimes I wonder where I got the ideas from for some of the songs. There are things that wouldn’t even occur to me now.”

What’s coming up?

“I was halfway through recording the next album when I got cancer, so that’s had to go on hold while I’ve been working on getting better. I had rough guide vocals laid down, and when I listen to the tracks I think they’re some of my best work, so I’m looking forward to finishing the album. It’s going to be a really great record. I’m going on the road in the spring, which will be the first time I’ve sung live since the cancer on my tonsils.

“I’ve been doing my therapy and working hard. There’s a lot of pressure knowing that I’ve got shows booked, but it’s a good pressure as it puts a lot of focus on my efforts. I guess the album won’t be finished until I complete the tour, by which time I hope my voice will be back to full strength, which means the record probably won’t be out until 2025. It seems a long way off, but it will be well worth the wait.”

- Social Distortion is out now via Legacy Recordings.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.