Jim Root and Mick Thomson on the depression, wild gear experiments and chaos theory behind Slipknot’s devastating new album

The End, So Far was borne of depression and anxiety: it's the triumphant sound of the Iowa metal institution picking themselves off the canvas, turning the guitars up loud and digging in

For many bands who wrote albums during the pandemic lockdown, having extra time to compose and experiment was a bittersweet bonus. It allowed them to try new techniques, then revisit and fine-tune songs months after they were first tracked.

Artists had the flexibility to upgrade their home studios and record in multiple locations. Fiddling while Rome burned provided a temporary escape from a decaying world and an outlet to funnel their anger and frustration. All good things in a tragic and frightening time.

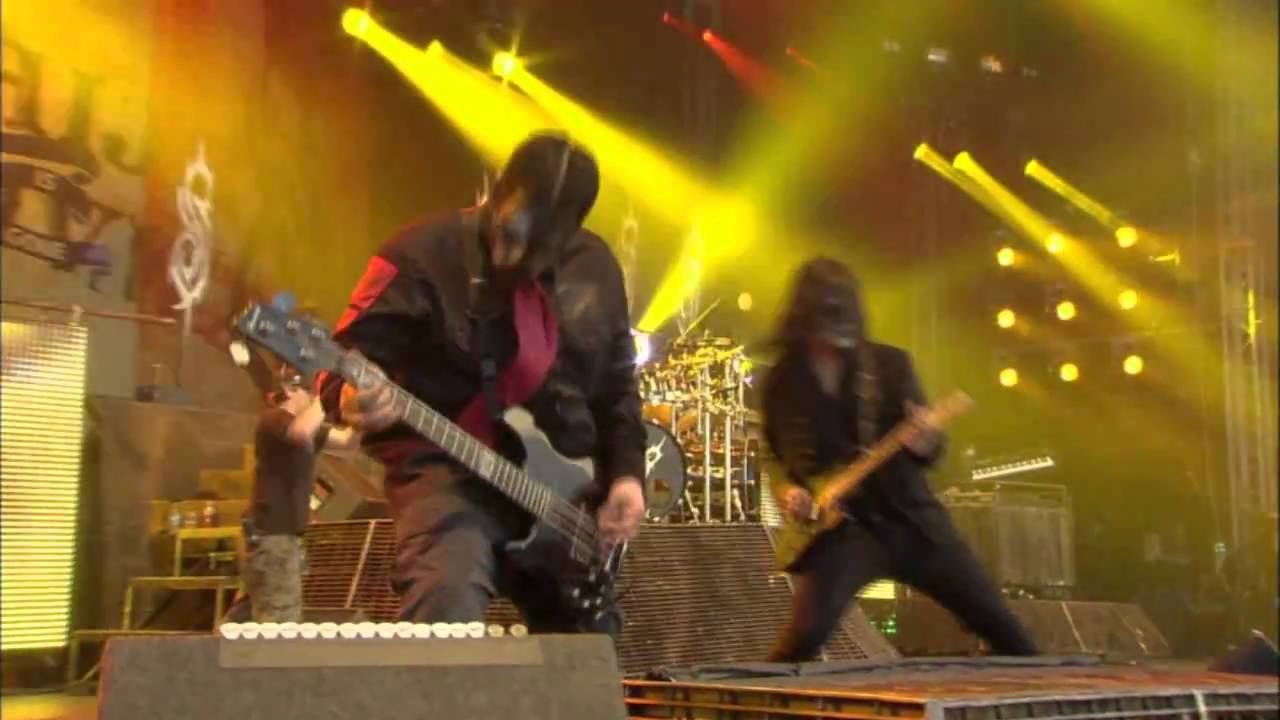

Listening to Slipknot’s seventh studio album, The End, So Far, suggests the nine-piece wrecking machine benefited from such a chance to explore a wide range of musical options, from moody and melodic elegies to vicious and chaotic tirades.

Throughout the record, ambient, effect-laden sounds collide with chuggy, downtuned riffs and tempos reel from sluggish to torrential, often in the same song. Like their last album, 2019’s We Are Not Your Kind, atmospheric interstitials are bookended by a schizophrenic hybrid of pop hooks, raging riffs and enough rhythmic variation to bewilder and enthrall.

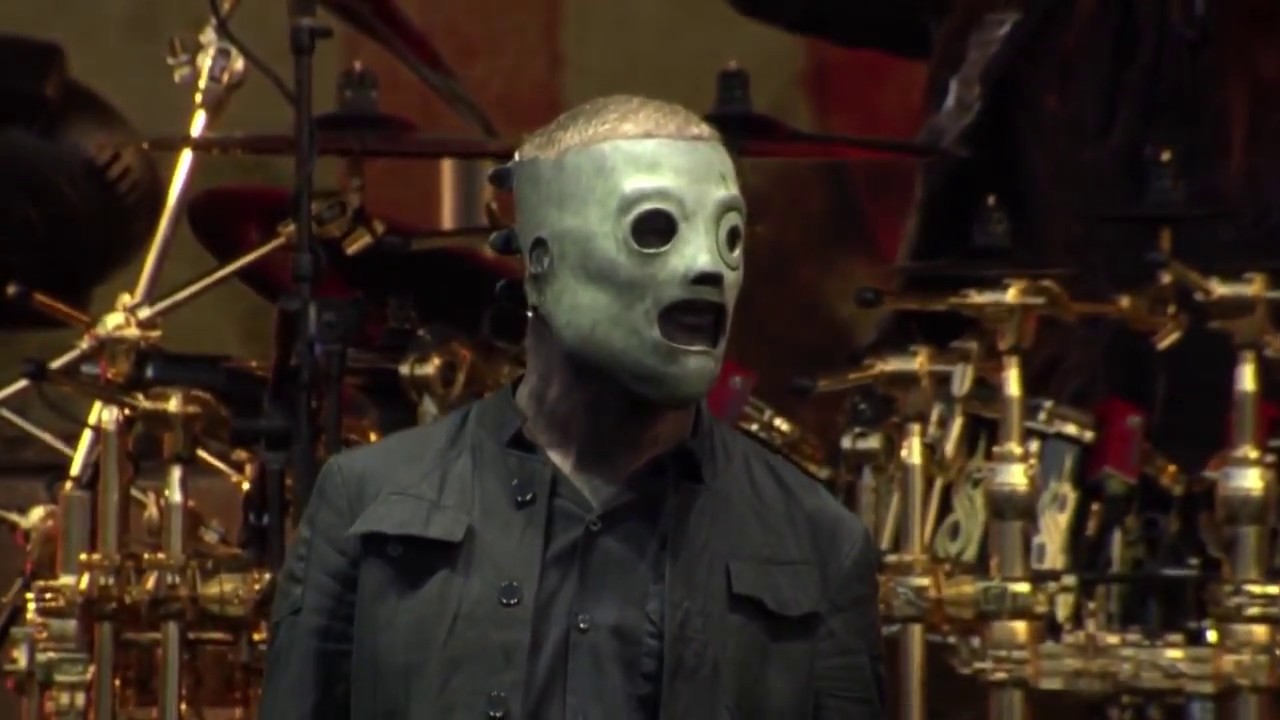

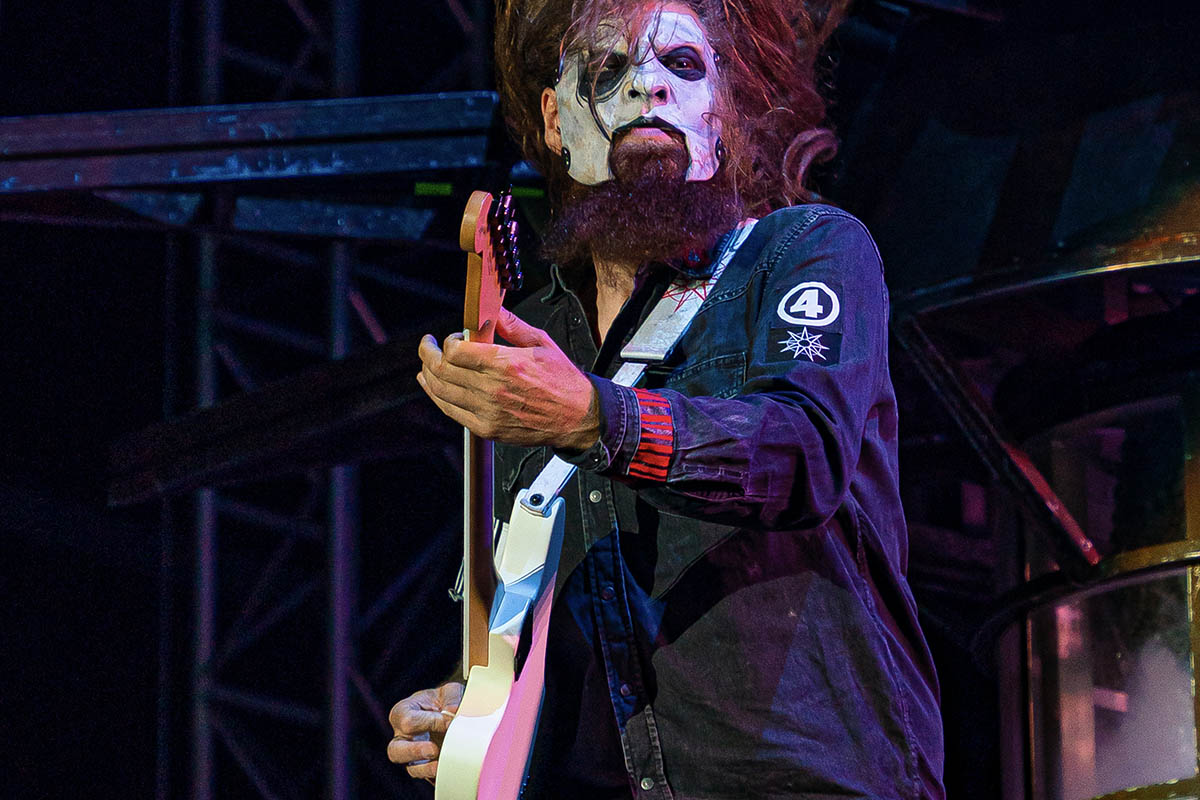

“We’re not just five guys up there playing metal songs like, say, Anthrax, Exodus or Testament. There’s so much more going on,” says guitarist Jim Root of Slipknot’s sawn-off-shotgun-to-the-head approach. “There’s orchestration going on with [keyboardist] Sid [Wilson] and [DJ and sampler] Craig [Jones]. There’s melodic vocals and screaming and piano and samples and all these layers and music styles.”

The End, So Far may not be Slipknot’s most accessible album, but it’s arguably their most eclectic and enduring, an inescapable, enigmatic nightmare of sound that alternately soothes, stomps and slashes. Many of the songs will instantly appeal to fans of the band’s tribal death, thrash and new-American-metal classics like Pyschosocial, People = Shit, and Duality.

However, hordes of “maggots” (the historic diehards) will likely be dismayed by some of the other tracks. Slipknot seem to take a perverse glee in this inevitability, which may explain why they open the album with Adderall, a melancholy, cinematic cut redolent of Radiohead and Trent Reznor. Sampled choir snippets merge with layered atmospheric guitars, fraying the nerves without a single distorted power chord.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Elsewhere, Medicine for the Dead blends warbling industrial noises into a melange of evocative arpeggios, clanking xylophones and palm-muted guitar chugs, and De Sade intertwines militant beats, a honey-sweet chorus and glistening guitar shards with shreddy leads. The End, So Far includes bluesy bits, some soulful crooning and tons of swooshing, pulsing effects you definitely won’t find on an Anthrax album.

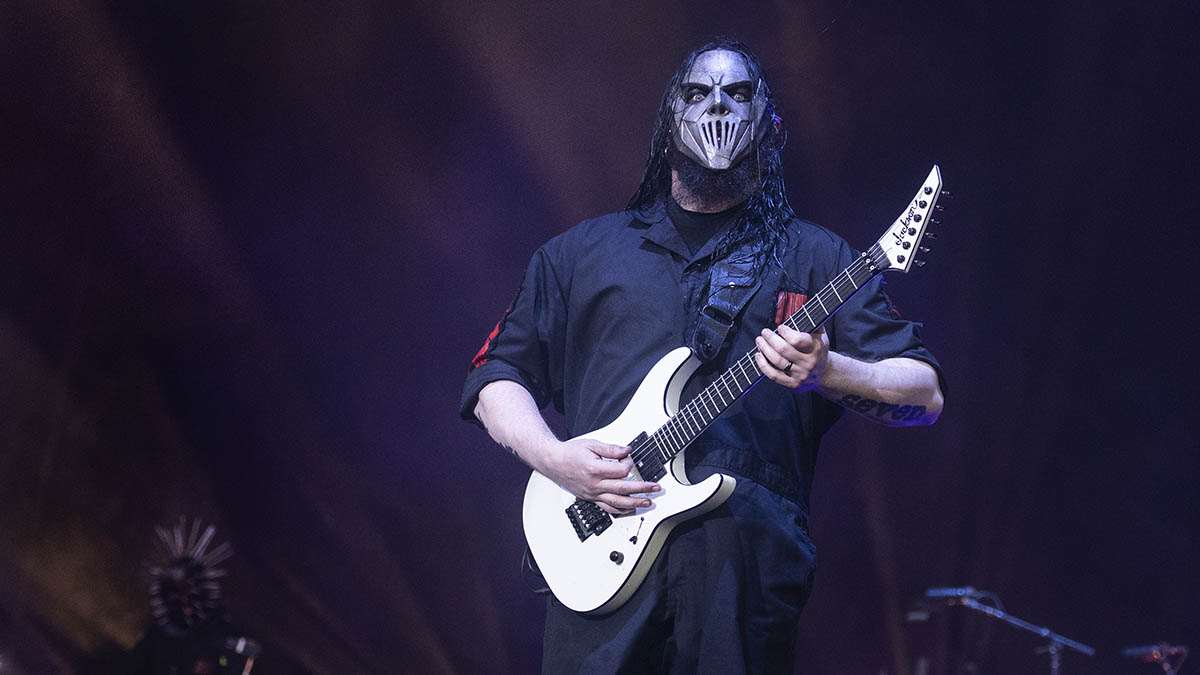

“I don’t think we intentionally did anything to piss anyone off,” says second guitarist Mick Thomson. “But I know some people are gonna hate it, and I don’t give a shit about what they have to say on the internet about how much I suck. I don’t even read anything on there that has to do with music [imitates blog post]: ‘Fuck those guys! Fucking sellouts!’ [implies blasé response]: ‘That’s fine. That’s wonderful. Have a great day. Oh, and your mom says you gotta fucking take the garbage out after your fucking homework’s done.’

Considering the intricate yet coherent results, what’s most striking about The End, So Far is that Slipknot had neither an abundance of time to work on the album nor a surfeit of material to choose from. When they entered the studio with co-producer Joe Barresi, demos were half-formed, Root – usually one of the band’s main songwriters – was almost too bummed out to pick up his guitar, and no one had rehearsed the chunks of music that were being considered.

“We were flying by the seat of our pants,” Root says. “Someone would go, ‘Okay, this is all we got. This is what we’re gonna build from.’ And we’d be off. I’d listen to something and go, ‘This is what I want to play on.’ I’d turn to Mick and go, ‘Okay, we want two guitar parts here that are different. Do you want to take the low one or the high one?’ And maybe he’d say, ‘I like the low one.’ And we’d play together until we came up with something.”

The situation was a producer’s second-worst nightmare. The only more stressful scenario is when everyone in a band is either constantly drunk, strung out on drugs or feeling left out of the creative process, as was the situation for Slipknot’s 2008 album, All Hope Is Gone.

Having mixed the last two Slipknot albums, however, Barresi was prepared for the unusual. He just wasn’t completely ready for the avant-jazz-style sessions that went down at his home studio and at Henson Studios in Los Angeles. Equally unsure of the outcome, everyone entrenched themselves and started spitting ideas. And alchemy occurred.

In a series of revealing and fascinating conversations, Root and Thomson address the extemporaneous recording style that yielded one of Slipknot’s most dizzying and cathartic albums, the setbacks that threatened to cripple their efforts, how they conjured mind-bending noises out of the ether and how they’ve made it through more than 25 years by adapting to, learning from and maximizing every bizarre scenario in which they find themselves.

I: The art of random chaos

Your 2019 album, We Are Not Your Kind, was filled with experimental interludes and structured almost like an epic, conceptual piece. The End, So Far is just as creative and artistic, but it seems more like the product of an attention deficit-afflicted nation being bombarded with a vast array of stimuli.

Was the goal to take contrasting clusters of noise and melody and stitch them together in a way that somehow holds up as resolutely as an AC/DC album?

Mick Thomson: “There’s never a plan. I’m totally against the idea of following expected paths because even if you try to do that, it doesn’t work out the way you thought it would. Even if you think you know what’s going on, unexpected things always happen. Life always changes.

Jim Root: “Our sound comes in part from constantly changing up the formula. We’re still trying to evolve as a band, and I am trying to evolve as a songwriter. And now we’ve got our new bassist Allesandro [Alex Venturella] (ex-Krokodil, Cry for Silence), and he’s an amazing schooled musician.

“He was tech’ing for Brent Hinds of Mastodon, and he’s a friend of mine. I said, ‘Hey, man, would you rather be onstage playing bass or helping Brent out?’ He jumped at the opportunity. And then he brought some song ideas to the band, so that duty came off me a little bit.”

Up until 2008’s All Hope Is Gone, the late bassist Paul Gray and the late drummer Joey Jordison co-wrote much of the material. Has the band changed significantly with different writers at the helm?

Thomson: “We’ve always been the way we are. Every song has a different story and goes through all sorts of different processes to become what it is. No one writes something and goes, 'Here, dude, check this out' and then there’s a song. It’s never worked that way with Paul and it doesn’t work that way now. Paul could write a song, but when we were done with it you may not even recognize it anymore.”

Do you feel different about the creation of The End, So Far than about your previous releases?

The only thing I’m really bummed out about is that we were so unprepared, and it was the first time we got to work with Joe Barresi as a co-producer. I could sense a little frustration in him sometimes because we weren’t well-rehearsed and ready to go

Jim Root

Thomson: “So much was going on the whole time that nothing seemed fucking real. Now that I’m thinking about things and what we just recorded, it’s almost like a dream. That’s the way everything has been for me ever since we couldn’t tour anymore because of the pandemic.”

Root: “We were all crazed. We had zero time for pre-production and it was like we were learning and building and adding to this meal we were making as we were eating it. But we tend to work well under pressure and we got a great record out of it.

“The only thing I’m really bummed out about is that we were so unprepared, and it was the first time we got to work with Joe Barresi as a co-producer. I wanted to come to Joe with our A game. I could sense a little frustration in him sometimes because we weren’t well-rehearsed and ready to go. We were still writing and working on the songs.”

Do you think The End, So Far is darker and more chaotic than much of your prior output because of the two-year horror show you experienced as you created it?

Root: “Yeah, because no one had rehearsed together. If we were gonna rewrite parts of the demos it was gonna have to happen right there on the spot as we were recording it. We were lucky that we were in the position to come up with these parts because we were layering the record rather than playing it.

“It wasn’t my favorite way to make a record, and [it’s] not Joe’s favorite way to make a record. But because of the circumstances with Covid and the fact that we all live so far away from each other, and we had a budget and a schedule we had to stick to, we had no choice.”

It seems like you’re trying to create a puzzle with 1,000 pieces, but the puzzle doesn’t have a guide image to follow and the pieces don’t all have compatible parts.

Thomson: “It’s unglamorous, but yeah. There’s all this talk about the vision for this record. In reality, a lot of it is taking a part and duct taping it onto some other part, and then doing it again. But it’s not fucking throw-and-go.

“Something might start with a part someone demoed with EZdrummer. Another thing could come from fucking riffs that were three years old that we jammed on. Everything filters through the band and gets rebuilt and constructed. But wherever it started, and whatever it goes through, it always turns into a Slipknot song.”

If you took the material everyone contributed to the songs on The End, So Far and started working on them today, having never heard them before, would the album be pretty much the same?

Thomson: “No. It would be completely different. That’s what a lot of fans don’t understand. There’s a nucleus point somewhere, and then the rest of the band comes in and all sorts of other parts change and morph and mature and grow and get cut and rearranged. Everything could be different at any time.

“Right now, in this situation, this is who we are. If you gave us six months to go record it again, it would sound radically different because it would be a year and a half later. We’re different people. We’ve had different experiences than what was happening when we did this record. We could have the same vision. We could try to put out the same thing, but it wouldn’t even sound close.”

Amps and Cabinets:

• Bogner Helios Eclipse with “fat mod”

• Friedman BE-100 Deluxe

• Orange Rockerverb 100 MKIII

• Orange PPC412 cabinet with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects:

• Dunlop DCR2SR Cry Baby rack module

• Dunlop JH1D Jimi Hendrix Wah

• MXR Carbon Copy analog delay

• Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

• Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octavio

• Boss NS-2 Noise Suppressor

• MXR Auto Q auto wah

• Maxon AF-9 Auto Filter

• Origin Effects Cali76 Compact Deluxe compressor

• Electro-Harmonix Small Stone Nano phaser

• Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Nano reverb

• Eventide H9

There are some complex, multifaceted songs on the album, such as Medicine for the Dead or Hivemind. Were those particularly hard to get your head around?

Thomson: “We’re always dealing with multiple parts that come from totally different directions. That’s just Slipknot. If we’re stuck on a part that just isn’t working, and you don’t come up with something within a couple hours, you’ll spend the next three days and then never have it.

“Sometimes it doesn’t work and you gotta drop it entirely and sometimes you just need to walk away and look at it again later or kick it to [vocalist] Corey [Taylor] and let him write some words for what you’ve got.

“If there weren’t words to it already and he comes up with something, that might trigger something else, and you completely rewrite it because of his lyrics. Sometimes we’ll get stuff back that he did a demo vocal on, and then we’ll be like, “Okay, that riff’s gone now and this other thing moves to the front. Every song has got its own different kinda weirdness that it goes through and it’s never really the same.”

Root: “I try not to get married to anything that I write. Let’s say I write a full five-minute-long arrangement. I’ve layered it up with five guitars and synthesizer parts and put bass on it and programmed all the drums for it. I might have put 30, 40, 50 hours into one arrangement.

Amps and Cabinets:

• Omega Ampworks Obsidian (with KT66 power tubes)

• Omega Ampworks 4x12 FL Standard cabinet (with Eminence DV-77 Mick Thomson signature speakers)

Effects:

• Boss GX-700 guitar effects processor

• Electro-Harmonix Bassballs envelope filter (vintage)

• (Dead)FX “I Can’t Feel My Face” Super Fuzz

• MXR Dyna Comp

• Dunlop Billy Gibbons Siete Santos Octavio Fuzz

• Dunlop DCR2SR Cry Baby rack module

• Wampler Tumnus Deluxe overdrive

• Warm Audio Foxy Tone Box octave fuzz

• Stone Deaf FX Noise Reaper

• Line 6 HX Stomp (for reverb and delay)

• CIOKS DC7 power supplies

Switching:

• Radial Engineering JX44

• KHE Audio ACS 4x2

• RJM Effect Gizmo

• RJM Mastermind GT/22 Controller

• MIDI Solutions T8 MIDI Thru box

Other:

• Furman P-1800 AR power conditioner

• Shure Axient wireless

“When you sit up all night putting something together by yourself, you tend to feel close to it. But if I hand that to Corey and he says, ‘Hey, can you make this part longer?’ Or, ‘Nah, I don’t like this part,’ I don’t get butt-hurt about it.

“And I don’t take it personally because I know we both want the song to be great and if changing my parts around makes him come up with a better vocal line for this part, then I’ll spend another five hours on it to get it to where he needs it.”

Do you ever pick up your guitars and just jam to come up with a new part or find a segue to a part you’ve already written?

Root: “That’s the way Mick works. If we’re in a room playing and he comes up with an idea, he’ll play it over and over until somebody’s like, ‘That’s a fuckin’ riff! We’re gonna turn that into a song!’ Or I’ll show him something and say, “We need a part here.” He comes up with a lot of stuff like that. Or he will be fucking around with an effect and that will spark a song idea.”

Thomson: “But that’s why it was really fun to experiment in the studio this time. We’d have something and then I’d throw a bunch of other different amps up and go, ‘Okay, let’s try this.’ I would double a riff but then change it a little.

“Next thing I knew, that doubled riff was the main part with a totally different amp sound and my normal tone had disappeared. It was just a bizarro process. It was almost a backwards fucking record from the way we’ve worked before.”

Slipknot has always thrived on creative chaos. Does the band’s aesthetic rest on the idea that control is an illusion?

Thomson: “I don’t know if any band could ever have an entire vision for something and then achieve it. So we don’t even try because everything is dependent on so many things. Every one of our records is different because they’re reflective of all the people in the band and the input they have in the songs. And that input has a lot to do with who we are.

“We’re all in different spots in our lives and every time we do stuff together, everything sounds a little different. Maybe one of us is burned out from playing something a certain way too many times, and maybe someone else wants a little more of another thing.

“So, now we’re pushing in new directions we’re not even aware of because we’re processing it as you’re doing it. It’s like you let your gut direct you and then your brain doubles back later and tells you what your gut did.”

Do you think your gut reaction to a musical passage is usually the right one?

Thomson: “I think you can overthink things until you don’t know which way is up or if what you just did is any good. This album is looser and darker, but is it better? That’s up to anyone’s perception on any given day. There’s days when I love a song and then another day I hate it. But that’s what’s cool about what we do. You’ve got all these conflicting factors and everything is the product of these different people involved, So we’re always in a different spot.”

Does rolling with the chaos make you rely on one another more instead of trying to be the main creative force?

Everything feels a lot more collaborative now because, in some ways, we’ve grown up to be inquisitive children picking each other’s brains

Jim Root

Root: “To me, everything feels a lot more collaborative now because, in some ways, we’ve grown up to be inquisitive children picking each other’s brains. ‘Oh hey, what’s that thing you’re doing there? How did you do that? Will you show me?’ Or I’ll hear something Mick does and I’ll go and grab a pedal to see if I can come up with something that will compliment his part.

“We’ve learned how to communicate and we’re trying to understand where everyone else is coming from. I just wish some of these songs on this new record had the chance to evolve a little bit more. Now that we’ve been away from the recording process for a few months, I’m like, ‘Shit, man, I have such a better idea now for that part. I wish I could re-record that thing.’ Or ‘I have this riff that I think would fit better in that section.’ And that’s when you see us play live – I tend to improvise a lot or add things into the songs.”

If We Are Not Your Kind was like your twisted version of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, with all the different interstitials leading into these epic songs, The End, So Far feels like a Pink Floyd record playing simultaneously with albums by Radiohead, Pantera, Slayer, Foreigner, Soundgarden, Ministry and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross.

Root: “It sounds like it’s all over the place because our influences come from all over the place and we’ve evolved to the point where we can get that across in the songs. This band is such a cornucopia of different personalities and musical styles and musicians in general. Me and Mick are basically self-taught metal dudes.

“Corey can sing anything. Alex is schooled in music, Clown came from a more indie rock world, and everyone else is very artistic in their own way and they bring their own approach to the songs as well.”

Slipknot isn’t easy listening, but, like some of the best albums by Mastodon, Tool, Lamb of God or even Yes and King Crimson, you have to earn the right to love it and understand it.”

Thomson: “It shouldn’t be too easy to digest or even categorize. When we did Vol. 3: The Subliminal Verses, I was listening to a burn of roughs in my car in Des Moines. The guys in the band Cephalic Carnage were playing in Des Moines that night, so I was playing the songs for one of the guys in the band and he didn’t know what to say.

“He was like, ‘This is just so different. What is it? It’s metal, but it’s not metal. How do you define it?’ And I said, ‘Stop trying to fucking nail it to a wall as something and just enjoy it as music.’

Punk always sounds like punk, but metal can go in a million different directions

Mick Thomson

“That’s what I’ve learned as I’ve gotten older because I was one of those kids that went, ‘Well, I only like this kind of thing and fuck you.’ So I understand how fans do that. But music is a huge thing. You don’t have to put yourself in a narrow type of pigeonhole. It’s an expression of who you are and what you do, and if you’re true to yourself it just comes out of you and it is what it is.

“That’s what I love about metal more than a lot of other music. You can draw from a lot more places. Punk always sounds like punk, but metal can go in a million different directions.”

II: Sinking into the depths

Jim, Did you play a substantial role in the songwriting for The End, So Far?

Root: “Mostly, I helped shape and structure songs in the studio. But I didn’t write and bring in stuff the way I did before. I was majorly involved in the writing from Vol. 3: The Subliminal Verses. And then I got in a bit deeper on All Hope Is Gone.

“I wrote most of .5 The Gray Chapter and We Are Not Your Kind. But then the pandemic happened and nobody could be together. I was home alone and I got stressed out and depressed. So my contribution was minimal for this. It’s a good thing we had Alex stepping forward and picking up some of the slack along with [percussionist and artistic coordinator M. Shawn Crahan] Clown, who’s becoming a lot more involved in song arranging.”

Guitars were depressing me. Everything was depressing me... whereas previously the guitar was an outlet for me to escape stuff, this time when I looked at it, it just reminded me of all the things that I wasn’t able to do because of Covid

Jim Root

Did Alex’s ideas fit into the nebulous metal realm of Slipknot?

Root: “When I first heard a lot of the arrangements, I thought, 'Oh fuck, this doesn’t sound like Slipknot to me. We’ve got a lot of work to do.' I was kind of freaked out. What I heard was the symptom of having somebody that isn’t in our age group and wasn’t influenced by the same music.

“Alex was a Slipknot fan so he sounds like somebody that was influenced by Slipknot trying to write for Slipknot. But he had some good ideas, so we Frankensteined a couple of different parts between me, Alex and Clown, and things started to take shape. It was a huge group effort, but I was grateful Alex wrote the stuff he did because it taught me – not just about songwriting and arranging – but also about humanity, humility, ego and friendship.

Even if you weren’t able to write songs, did picking up the guitar during the pandemic help take your mind off the state of the world?”

Root: ”No, guitars were depressing me. Everything was depressing me. It’s weird how the wires in your brain will cross up and whereas previously the guitar was an outlet for me to escape stuff, this time when I looked at it, it just reminded me of all the things that I wasn’t able to do because of Covid. So, this positive force in my life turned into this negative thing, which would’ve been absolutely fucking horrifying if I hadn’t been able to pull myself out of it.

“Now I pick up a guitar and I’m like, ‘What would I do without this?’ But back then, I was so far from that place. I was losing any sense of positivity. I had zero purpose at all. And I thought, ‘What difference does it make if I’m here or if I’m not here? What good is my existence? I’ve pretty much accomplished everything in life that I’ve set out to accomplish. How do I set new goals and why should I bother?’ That’s what was going through my head and it was scary.”

Once you came out of your funk, were you able to write again?

Root: “I tried to do some stuff. If I had felt a little more confident and positive, I would’ve said, “Oh, this is great. I’ve got all this downtime to sit and write and be creative.” I normally write in my house, but I had a bad leak and there was water damage so I had to try to find someplace different to set up my computer and write.

“It just didn’t feel right and gave me anxiety to try to work that way, which made me give up trying. I wasn’t in my comfort zone even being by myself. I was trapped in my head and I overthought everything.

“I was thinking about a bad relationship I was dealing with and trying to figure out the problem. ‘Am I the problem? Do I need to try harder?’ I was questioning everything and coming up with no answers and getting more depressed. I got to the point where I was really struggling to even want to see the next day.”

That’s bad. What did you do to regain some stability?

Root: “Finally, I got depressed enough and dark enough and sick enough of my own shit that I reached out for help and started seeing a therapist. And that really helped. They say men only seek out therapy as a necessity. They won’t go unless it’s their last resort.”

Did a doctor prescribe you antidepressants or anti-anxiety meds?

Root: “I think that might have been part of the problem. I have a lot of social anxiety and I’m a pretty introverted person. Whenever I’ve talked to a doctor in the past, they’ve prescribed me [antidepressants] like Wellbutrin or Zoloft. I’ve tried taking those things, and after about a week or two they seem to make my anxiety even worse and I have massive panic attacks.

“So I don’t think those really jive with my chemistry at all. Instead, I was prescribed [the anxiety medication] Xanax. I felt like I needed to take something to level me out. I think I got too reliant on Xanax and that made me not care about anything at all.”

Mick, were you also in a bad place?

Thomson: “Basically. Yeah. It seems like every plausible metric is fucked currently. I was in a very bad place a lot of the time.”

Were you angry and depressed?

Thomson: “Oh, I always am. When am I not? More than usual? Absolutely, sure. It’s been like a fucking horror movie. It’s the frog that doesn’t know the water in the pot he’s in is starting to boil. It’s turning up and we’re sitting in the fucking nearly-boiling water right now and we’re going, ‘Oh, this kind of sucks.’ If you woke up 28 Days Later-style, you’d say, ‘What the fuck happened to the world?!?’ It wouldn’t seem real, but in incremental steps toward where we are, you somehow deal with it.”

Was playing guitar therapeutic for you during the pandemic?

Thomson: “It’s always therapeutic for me to be doing something with guitars. I’ve got pedals all over my dining room table. There’s guitars all over the floor. I just work on shit and experiment and play.

“I’m always putting pickups in something or swapping out a bridge, just messing with stuff, adjusting the action and the intonation. And as soon as I’m done working on something, I’ll plug in and play with it for hours. What’s fun about it is that it’ll feel like I’m dicking around with something different and testing it out. So there’s an excitement about guitar because I’m being constructive.

“It’s not, ‘Oh, look. Employment. Guitar.’ During quarantine, I spent hours and hours on that to get everything dialed in right. I played a bunch for sure, but my mental getaway comes from fixing shit and modifying stuff.”

Jim, after you went through life coaching, was it easier to start writing again?

Root: “A lot of my arrangements on The End, So Far were things I had been trying to do on my own, maybe for a solo album, around the time we did The Gray Chapter or We Are Not Your Kind.

“There were just a few songs I had written in the interim that I wasn’t really in love with, and a bunch of sounds and effects and atmospheric parts I recorded. I also did some stuff that was real riffy, but not songs. I handed the hard drives to our engineer and Clown and I said, 'Here’s some stuff. See if you can do anything with these.'

Joe Barresi has a certain openness to trying different things, which I loved. He got me to use a bunch of different passive pickups with great effect on a bunch of spots

Mick Thomson

Did entering the studio get your creative juices flowing again?

Root: “I went through weird phases. It was time to record the album, but I was still in songwriting mode. There was one idea I had [for Acidic] that was really bluesy and I experimented with key changes, which I don’t normally do. And I found myself going back to playing a lot of speed metal and thrash metal riffs, and we recorded a lot of those.”

III: Salvation through sound

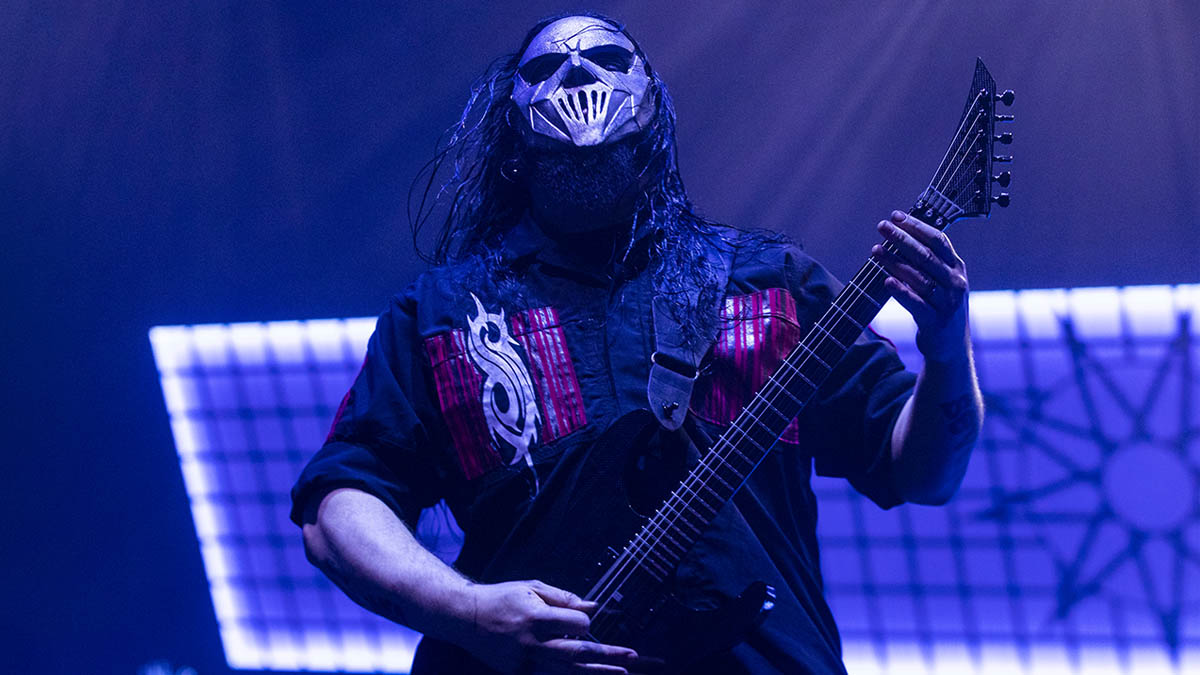

You worked with Joe Barresi, who has entered the studio with many heavy bands, but never one as aggressive as Slipknot. Did you click right away or was there a learning curve?

Thomson: “It always takes some time to learn each other’s style and build up that trust. But I wasn’t worried because Joe’s history with tones is unreal. Just the fact that he engineered the Kyuss records I always loved so much sold me on him.

“Joe has a certain openness to trying different things, which I loved. He got me to use a bunch of different passive pickups with great effect on a bunch of spots. So that’s something I’ve reopened my mind to after 20 years. I play passives and stuff at home, but I wouldn’t even consider taking a passive pickup guitar to go play metal in somebody’s basement.

“But dialing that back a bit was fun because it forced me to really dig in. I’ve got a heavy right hand anyway, so it’s not much work for me to dig in more to get more out of those strings.”

Root: “Joe is extremely knowledgeable about sounds. Fuck, listen to Tool [whose albums Barresi has engineered]. He knows how to get the best out of everyone. Working with him has made me go to my live rig, and me and my tech are reworking the sounds on my amps now. I’m gonna see if EMG can make me a passive style of pickup, like an HZ, which would have a different vibe from the compressed pickups I’m using now.

“I’d like to dive deeper into that world and go a bit back to the roots of everything – using an overdrive pedal to get that extra juice out of the amp instead of jamming the preamp gain – that kind of thing.”

I had so much fun experimenting with all the fucking gear. There’s so much going on that it’s more in your mind than in the pedals

Mick Thomson

The new music isn’t always a fist-in-face attack. Just as often, you seem to express a different kind of heaviness with ambient passages and experimental techniques. It’s like you took a box of random effect pedals, connected them to an amp, and made crazy sounds for hours.

Thomson: “I had so much fun experimenting with all the fucking gear. There’s so much going on that it’s more in your mind than in the pedals, but there are all these soundscapes that you can create in all these different ways. This is the first time ever on a record that I didn’t have one guitar sound as my attack tone.”

Did you have go-to set-ups depending on whether you wanted a crushing tone, a middle-of-the-road tone or an ambient tone?

Thomson: “I had a different amp on every song – multiple amps on every song. And then there were all these other layers; we played with radically different amp combos. Joe’s got a bunch of stuff, which is like a toy chest. And I’ve got lots of my own stuff, too. The funnest thing was putting together non-metal things – different combinations that wouldn’t necessarily be your first choice for a metal tone – and then just playing the living shit out of them.”

Did you come up with any combinations that surprised you?

Thomson: “There were times when I’d be playing heavy parts with a passive pickup guitar with a fairly low output into a Marshall 800 with an overdrive. I’d be picking real fucking hard and it sounds like I have tons of gain on there but it felt damn near clean in my hands picking it. You have to beat the living shit out of it, and a lot of that translated in a great way.”

How are you still around and making some of the most creative and powerful music of any heavy band more than 25 years after your self-release demo CD, Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat.?

Root: “We’re getting to that point in our career where we’re all in this together. We all want to do the best we can for the role we play in this band, and when that becomes the priority, that’s when you put ego aside, put all that bullshit aside, and work together to make something great.

“I don’t think you choose to do this for a living because you’re the most well-adjusted human on the planet. It’s just too hard to stay stable and your life is just too chaotic to have any sort of anchoring.”

Thomson: “We’d be stupid to keep doing this if we didn’t love it. There’s too much bullshit. I think the biggest problem that breaks up bands is when everyone comes in with fucking egos. When egos and bullshit start to make a person nutty, that’s when problems happen and musicians start to hate each other.

“Fortunately, in the first few years after we blew up, nobody’s ego got too far out of check. And that can happen real fuckin’ easily. You take a bunch of fucking dork kids and apply money and fame.

“Someone’s always got someone in their ear telling them shit about one thing or another. And most bands end up eating shit because they just can’t personally navigate everything and manage to keep it together. I’m just glad we’re all fucking able to deal with everything we’ve experienced. And that’s because we all know we have our roles. There’s no I, there’s us.”

- The End, So Far is out now via Roadrunner.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.

![Slipknot - Nero Forte [OFFICIAL VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/JGNqvH9ykfA/maxresdefault.jpg)