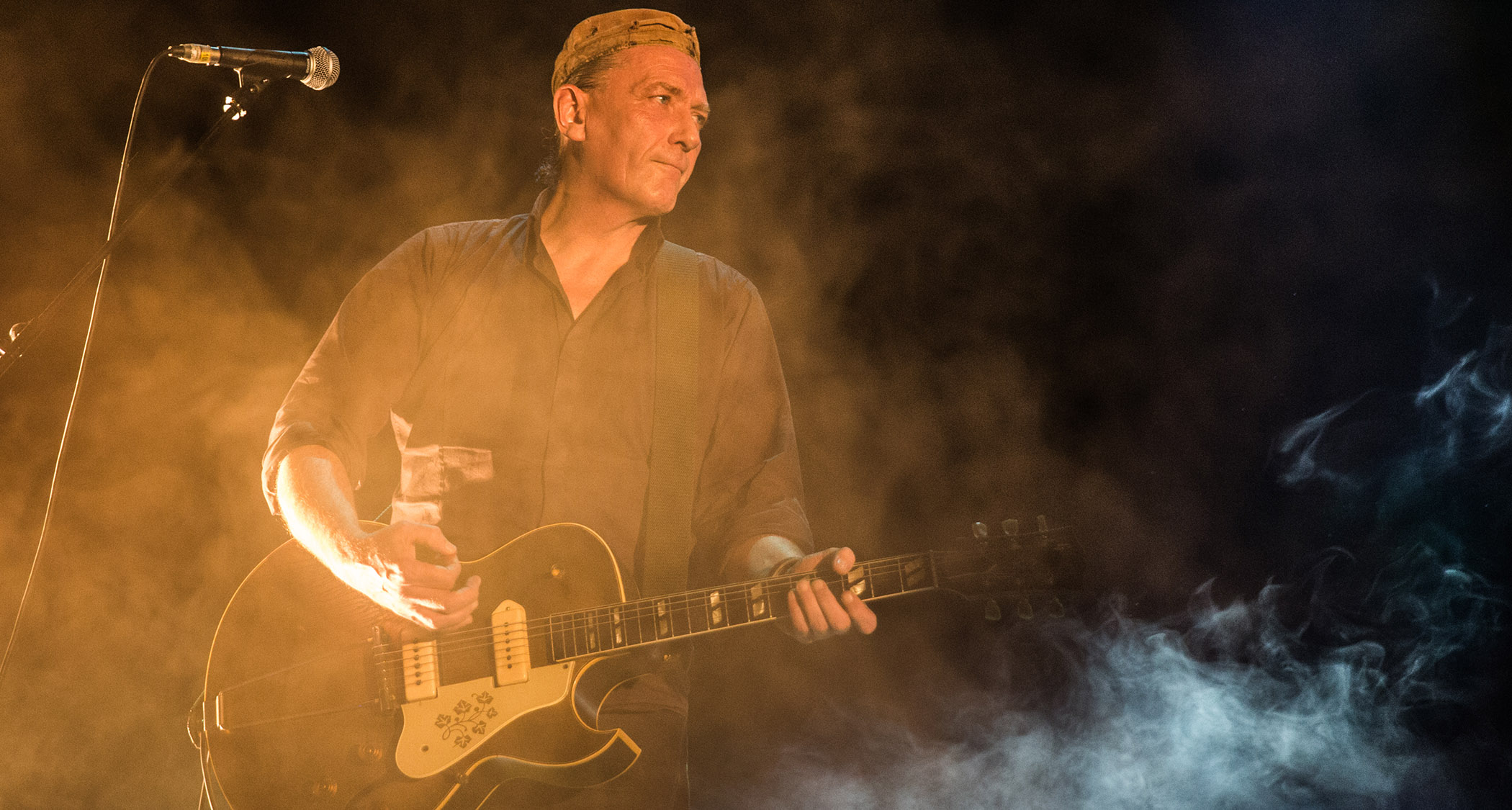

Shez Raja: “The harmony in Indian music is super-simple – where it gets mind-bogglingly, face-meltingly interesting is the rhythm and the melody“

The mighty Indojazzfunk bassist returns with his most ambitious album yet, Tales From the Punjab. We meet the maestro...

London-based songwriter and bassist Shez Raja made his name touring with Elephant Talk, Loka, and MC Lyte before embarking on a session and solo career.

His earlier records featured stellar musicians such as Wayne Krantz, Trilok Gurtu, Mike Stern, and Randy Brecker, and his new album, Tales From The Punjab, continues to explore a rich musical and cultural range of inspirations.

The album, the result of Raja’s 2020 visit to Lahore in the Punjab in Pakistan, features a host of guests. These include bansuri flute player Ahsan Papu, sarangi player Zohaib Hassan, tabla maestro Kashif Ali Dani, singer Fiza Haider, and cajon guru Qamar Abbas.

If you’re not familiar with these instruments, or indeed how a bass guitar meshes with them, you’ve come to the right place – as the man himself is here to explain how it all fits.

Tell us about the inspirations behind the new album, Shez.

“Back in early 2020, just before the pandemic, I went on an adventure, traveling around the Punjab. My dad’s Asian, and what I wanted to do was explore my Asian heritage as a musician. I’d only been there a handful of times in my adolescence, so a way to do this was to immerse myself in the music. It’s been incredibly inspiring.“

Where did you record?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“In Lahore, which is an incredible city. I linked up with some mind-blowing musicians, and I was honored to play with them. I met them in the recording studio, and basically hit record. We started playing, and I knew within a few moments that something really special and magical was happening.“

Tell us about the instrumentation.

“There’s the bansuri, which is a wooden bamboo flute. It was played by Ahsan Papu, who is a legend. He played with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the legendary qawwali singer, and not only is he a master musician, he makes his own instruments. He brought about six of them to the studio. Then there’s the sarangi, which is a fretless bowed string instrument.

“I love the sound of it. It’s got a vocal quality to it – a real shimmering sound, almost like a horn. You hold it vertically and play it with a bow. The guy who played it, Zohaib Hassan, is an innovator, because you normally play this instrument with three fingers on your left hand, and he uses his fourth finger, which opens up a lot more possibilities.“

Is there a tradition of bass guitar in this kind of music?

“None whatsoever. The other musicians told me, ‘This is completely new – this music has never been done before.’ I was just following my heart with this album.“

So how does the bass fit in?

“In a really organic way. The instrumentation is radically different to my previous six albums, because instead of a drum kit, we had tabla, and there were no harmonic instruments at all. Not only that, everyone was playing over a continuous drone from an electronic drone box. In addition, when I was soloing, I put double stops in more than I normally do, and I was surfing through multiple modes.“

We did use some Western scale forms on the album, but I was also using North Indian Hindustani thaats, which are what they call ‘parent scales’

Talk to us about the theory behind the music.

“We did use some Western scale forms on the album, but I was also using North Indian Hindustani thaats, which are what they call ‘parent scales’. Conveniently, six of them are the first six modes of the major scale that we use in the West.

“The other four are super-interesting. You’ve got the Bhairav scale, with a flat two and a flat six, and the Poorvi, Marwa, and Todi scales. I’ve been playing these scales for a number of years anyway, but now I had the opportunity to do that in a pure context. It was so much fun.“

What about the rhythms?

“Well, the harmony in Indian music is super-simple, but where it gets mind-bogglingly, face-meltingly interesting is the rhythm and the melody. Not only have you got the thaats, but the performance of the melodies is also rich in ornamentation, which gives the music expression and emotion.

“In Western terminology we’d call it grace notes, glide notes and vibrato, but the vibrato is a special kind of oscillation using trills and microtones. And on top of all that, there are hundreds of ragas, which are basically sequences of notes, or rather interpretations of the thaats. They have very specific conventions around the order in which you play the notes.

“For example, if you go from the fourth to the second, you can never play the third in between, or if you go from the fifth to the octave, you can only play the sixth or the seventh between them. All these rules are designed to produce a certain emotion in the player and the listener. Melodically, it’s just another world.“

This music is in my blood. I picked up an appreciation of its musical language through osmosis while I was growing up

What blows my mind is that your bass parts in the album are really fast and fluid, yet you’re navigating through these strict, complex conventions as you play.

“Well, this music is in my blood. I picked up an appreciation of its musical language through osmosis while I was growing up.“

At the same time, you must have worked hard to get it under your fingers.

“Oh yeah, exactly. For years, I’d get up in the morning, do some meditation, and then spend crazy amounts of hours on bass. I mean, hours and hours!“

What bass gear did you use on the album?

“I used my custom Fodera Emperor five-string in tenor tuning, which really suits my style because I like high-register soloing. It was useful for the chord voicings on this album, too, as well as being perfect for loads of low-end groove. I love that kind of hypnotic groove playing as well. My bass has a wenge fingerboard, which gives me a whole warmth that is a property of that tonewood. I’m also endorsed by Aguilar and I use DR strings.“

Any effects in the chain?

“My effects setup is central to my sound, so I use a Boss GT-10B multi-effects unit. My aim with effects is to create a distinctive sound for each composition. The reason why I use that particular unit is that it has two channels. I keep one channel for my pure, clean tone and the second one for my effects.

“On this album, I was going for a more natural, earthy sound, so I’ve used the effects in a very subtle way. How do you get your clean tone? When it comes to sound I think gear is crucial, but 70 percent of your sound is from your musicianship, what goes on inside your brain, the musicality you develop through years of experience, interacting with other musicians.

“Obviously the mechanics of your technique with your fingers is very important. I’ve been very lucky to travel to Cuba several times. I did a stint with a band on an island just off the Cuban mainland, and these guys were using amps that were in a dreadful state, but they sounded awesome, with unbelievable musicianship. Their timing, their choice of notes and their passion was all there – and it was a very interesting lesson for me.“

I apply certain tricks like playing in complete darkness, because that encourages and invites mistakes

How do you come up with songs?

“I’m a serial jammer and I have two or three jam sessions a week, often with drummers but with other musicians as well. I use those to try out new ideas and to bring in new suggestions as to how ideas can be developed, playing with no agenda in a completely free, organic, liberated way.

“I apply certain tricks like playing in complete darkness, because that encourages and invites mistakes. Something I’ve been working on is limitation – I find that can be an incredible artistic boost.“

In what way?

“Well, I remember talking to a lot of bass players during a Masterclass at the London Bass Guitar Show a few years back about the Apollo 13 space mission and how it was doomed from the start, because everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. Their oxygen tanks exploded, and the reserve tank was square-shaped and needed to be fitted into a circular, round-shaped port.

“Mission control solved the problem of fitting a square peg in a round hole with a highly creative solution, because of the limitations put upon them by the resources available on the spacecraft. To extend this idea to music, specific limitations I might impose could be a particular rhythm, or playing a very small number of notes. I demonstrated this by playing an A minor over a D7 groove, limiting myself to two notes, the A and the G. I had to dig really deep rhythmically to make it sound interesting for me, let alone the audience.

“A big benefit of this approach is that it can produce fresh, tangible ideas that you might not come up with if you had more options. Another is that when you do this over time, more sophisticated rhythm ideas embed themselves in your improvisational vocabulary. Your subconscious generates these interesting ideas which should make your solos more interesting.“

If it can soothe people in any way, or make a little difference to a handful of people, then its job is done

Do you ever use a looper when you’re coming up with musical ideas?

“Totally. If I find a cool harmonic idea with a chord progression that inspires me, I’ll record it, loop it, and then try out various melodic ideas. When I find a melody that I really love, I’ll then come up with a different chord progression or two, loop the melody, and change the chords underneath it.“

Thanks, Shez. The new album is great.

“Thank you. People seem to sense a lot of joy and a sense of peace in the music, and I thought, ‘What better time than a pandemic to listen to it?’ If it can soothe people in any way, or make a little difference to a handful of people, then its job is done.

“You know, I think whenever you play music with anybody, in any style of music, there is a spiritual connection, whether you like it or not. I was in a meditative state a lot of the time while we were recording, and that connection of my emotions to the songs is the reason why it’s the most heartfelt music that I’ve ever produced.“

- Tales From The Punjab is out now via Ubuntu Music.

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.

“I was playing stuff I don’t think James Brown understood. He told me, ‘You have to play the one – you’re playing too much’”: Six years after he quit touring, Bootsy Collins reflects on James Brown and George Clinton, and what he gets out of playing today

“When I first heard his voice in my headphones, there was that moment of, ‘My God! I’m recording with David Bowie!’” Bassist Tim Lefebvre on the making of David Bowie's Lazarus

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)