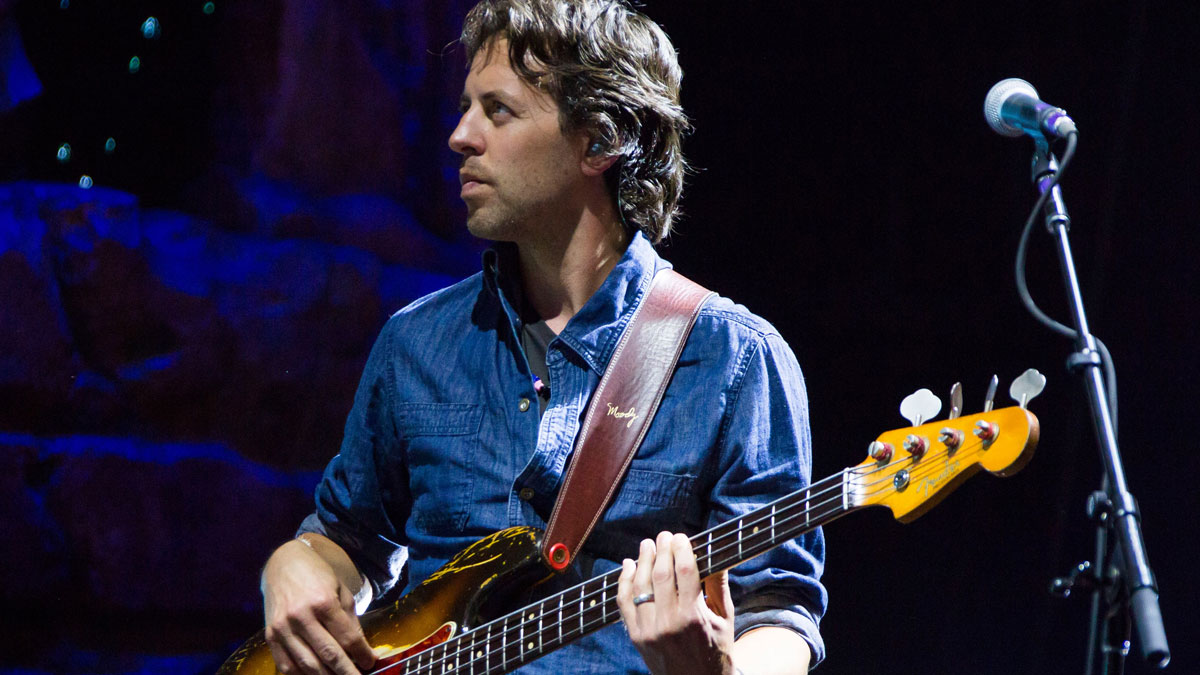

Sean Hurley talks touring with John Mayer and how to succeed in the LA session scene

"While I mostly played my Jazz Bass when I broke in, now it’s predominantly a P-Bass world"

"I like playing the roots," admits Sean Hurley, whose team temperament and early development has led to a somewhat unsung but highly successful career.

First gaining prominence as the bassist in Vertical Horizon via that band’s 2000 breakout smash, “Everything You Want,” Hurley has made his mark in L.A., co-writing Robin Thicke’s hit, “Lost Without U” (covered by Marcus Miller on his 2008 CD, Marcus), while maintaining a hefty pace as a studio doubler with everyone from Ringo Starr and Annie Lennox to Miley Cyrus and Colbie Caillat.

In addition, Hurley has been grabbing ears as John Mayer and drummer Steve Jordan’s groove go-between on three of the superstar singer/songwriter’s world tours.

Born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts on September 23rd, 1973, Hurley was raised on radio rock and took up saxophone in the 4th grade. At 11, he saw a local cover band and became enthralled with the bass player, who, upon learning of his interest, began teaching him.

A devout student, Hurley learned reading and harmony on “an SG-shaped Hagstrom,” while soaking up the influences of AC/DC and Rush. By 14, he was in demand in town bands for his big ears; he also began teaching bass at the music store where he worked.

Meanwhile, he “got hip to Jaco, McCartney, Jamerson, and Sheehan,” bought a Fender P-Bass, played in the school jazz band, and began teaching himself upright. Turning 16, Sean met Arlo Guthrie’s son on a club gig, leading to a summer tour with the senior Guthrie.

Upon graduation, Hurley headed to the Berklee College of Music for a semester. He replaced Matt Garrison in the school’s Yellowjackets ensemble, before Guthrie beckoned again with a national tour and live recording.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Hurley returned to Boston after the stint, settling into the blues club scene. There, he heard about and successfully auditioned for Vertical Horizon, in early 1998. Another blues connection, guitarist Bobby Keyes, began bringing Sean out to L.A. to write and record with Robin Thicke.

By 2000, with the breakout of Vertical Horizon and regular Thicke sessions, Hurley moved to Los Angeles. Thicke engineer Bill Malina started recommending him to other producers in town. With Horizon’s less successful 2003 follow-up CD leading to less road gigs, Sean worked his way up to 12-hour session days. Then came a call from “the Mayor.”

How did you come to play with John Mayer?

I had met John both at a Vertical Horizon show and at his own show, and we had some good conversations about life. Then in the summer of 2006, I was playing in L.A. with John’s guitarist, David Ryan Harris, and he came and sat in. Afterward he told me he had no idea I could also play R&B.

That December, he called me the night before he was recording “Lessons Learned” with Alicia Keys, for her album, and he asked me to play bass. He kept in touch, and in 2008 came the offer to do his summer tour, which was a blast. After it ended, John went in to make Battle Studies with Steve Jordan and Pino Palladino.

With the next tour approaching, John called me to come and play with him and Steve so they could try out a keyboardist. It was in a little room and they had my Ampeg B-15 there; we just jammed on cover tunes and it was my first time playing with Steve, which was a watershed moment for me!

Steve seemed to dig it, and I got invited to do the seven-month tour. This year, Steve had to move on to another project after the first part of the tour, so Keith Carlock is playing drums.

How much freedom do you get with the bass parts?

I’m pretty reverent about that; I try to play the parts as close as I can to what Dave LaBruyere and Pino did on the albums, unless the groove has changed, like on “Why Georgia.” I’m giving the parts my translation, but the original is still my intent.

However, John definitely leaves it up to the player. Before we hit the stage he’ll say something like, “Play without fear,” or “Take chances and make some mistakes,” or “Do your thing; play what you’re feeling.” Most times the intros are where it’s really loose; like on “Vultures”; John will just start playing something and I’ll let it simmer for 8 bars or so and I’ll make up a groove and start playing. Then Keith will join in, and we find our way to the song.

Ultimately, it becomes this self-policing, inward challenge; like, Oh, man, I came up with something better last night—I’ll play something cooler tomorrow!

What kind of calls are you getting as an L.A. session bassist?

The scenes I’m involved with are rock, singer-songwriter, young artists pop, and the occasional film date. I haven’t worked much on the hip hop, modern R&B side, other than with Robin Thicke. The bass guitar hasn’t really reemerged to supplant synth bass in those circles yet.

For me, it’s a mixed bag of doing a new artist’s demo one day and an established artist’s single or album the next. Similarly, I can be playing with some new players on one date and studio legends at the next. If your goal is to play bass for other people, L.A. has that in spades; you have almost every style of music here, and everyone has home studios. I’d say 60% of my calls are at home studios.

When I started in ’02, most of my calls were for bass alone, but from ’05 to now I’m almost always playing with at least a drummer and usually with a full rhythm section— often with the artist present. In that regard, the pendulum has definitely swung back.

Also, while I mostly played my Jazz Bass when I broke in, now it’s predominantly a P-Bass world. If you have a lot of guitar going on, the P-Bass has that little bit of snot to cut through, so the only real question is flatwounds or roundwounds. The other interesting aspect I’ve noted is while drummers, guitarists, and keyboardists tend to get pigeonholed stylistically, bass players have a much easier time genre-hopping.

How do you typically come up with basslines on sessions?

Nowadays, very few folks send you songs in advance, so first I’ll go into the control room with pencil and music paper, listen to the song, and write out a chord chart. Then, you usually have a discussion with the producer or artist as to what they’re going for.

Once the particulars of what the drummer is going to play and what I do in response are set, it’s mainly about what you can do to make the track special, whether it’s adding a passing tone here, or laying out there.

I feel like I’m good at reading the room, taking direction, and giving the producer what they want. Really, the hard part is coming up with the song; If I’m coming in to play on a good song, the part comes quickly.

In rare cases where I’m asked to step out and lead the track, I usually draw from tunes like [the Beatles’] “Come Together” or [Marvin Gaye’s] “Inner City Blues,” and I try to come up with a part that can stand on its own with just the vocal.

How do you navigate playing regularly with a rotation of top drummers?

Well, for the most part, we’re all playing to a click in the studio, so what’s fascinating and exciting for me, being lucky enough to work with these drummers, is how differently each one plays while still all being locked into the pulse.

Some drummers sit a bit behind, for which I’ll tend to play right on the beat; others play on the front side, so I can lay back my notes a bit more. Generally, I always feel like the drummer is the leader of the band. On a session, the drummer is usually going to set the tone with regard to the shape of the track and how everyone else reacts to them.

I consider myself in their service, working with them as opposed to trying to lead them or insert my opinion of where the time is. I try to play big fat notes with their kick drum while listening to their hi-hat because the downbeat and the subdivisions are the keys to nailing down the groove.

What advice can you offer to young bassists and what do you see for yourself going forward?

In the current climate, if you want to make a living as a bassist you should expand your horizons a bit; try to write, learn piano, guitar, and drum programming to at least a competent level. Bass-wise I’m all about fundamentals; learn chord harmony, run your scales, and perfect the root-playing, supportive role of the bass instead of trying to play fast or flashy.

Personally, being back on the road with John, I’ve found playing live to be a vital experience. I’d like to continue performing with great artists while balancing my studio schedule between writing and session work. I’ve heard veteran musicians state their goal as being able to play the best music with the best people. I consider myself blessed on that scale, so far.

Gear

Basses ’60 Fender Precision Bass with flatwounds, Fender Custom Shop ’60 P-Bass relic with roundwounds, ’59 Fender Precision Bass, ’69 Fender Jazz Bass, ’75 Gibson Les Paul Signature, Lakland 55-94 5-string, Kay K162 Pro Bass, ’66 Fender Mustang Bass, Cremona 3/4 acoustic bass (with Thomastick Spirocore strings, Underwood pickup, and German-style bow)

Strings and picks LaBella Slappers (.045–.105), LaBella Deep Talkin’ Flatwounds (.043–.104); .73mm Dunlop Tortex picks

Rig 1976 Ampeg SVT head (with ’74 SVT as backup), Diamond Blue Ampeg SVT810 cabinet, 1966 Ampeg B-15, Divided By Thirteen TBL 200 head and 1x12 cabinet

Studio Eclair Engineering Evil Twin Tube DI, EBS ValveDrive, Xotic Effect Bass BB Preamp

Chris Jisi was Contributing Editor, Senior Contributing Editor, and Editor In Chief on Bass Player 1989-2018. He is the author of Brave New Bass, a compilation of interviews with bass players like Marcus Miller, Flea, Will Lee, Tony Levin, Jeff Berlin, Les Claypool and more, and The Fretless Bass, with insight from over 25 masters including Tony Levin, Marcus Miller, Gary Willis, Richard Bona, Jimmy Haslip, and Percy Jones.

“I asked him to get me four bass strings because I only had a $29 guitar from Sears”: Bootsy Collins is one of the all-time bass greats, but he started out on guitar. Here’s the sole reason why he switched

“I got that bass for $50 off this coke dealer. I don’t know what Jaco did to it, but he totally messed up the insides!” How Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan went from buying a Jaco Pastorius bass on the street to fronting one of hardcore’s most influential bands