The Rolling Stones: The Main Attraction

Originally published in Guitar World, June 2010

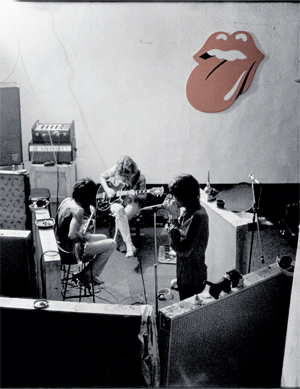

Critics snubbed it upon its release in 1972, but Exile in Main Street has become one of rock's greatest landmarks. Keith Richards recalls the making of the Rolling Stones' masterpiece and how the album's new reissue project became a walk down memory lane.

"To me, Exile on Main Street was probably the best Rolling Stones album as far as the connection between the band members," Keith Richards says. "We were coming up with song ideas like crazy. And the ideas were catching on. Everybody was going flat-out."

The anniversary reissue of the Rolling Stones’ landmark double album this May will provide a heavy blast of nostalgia to those who were around when Exile was first released, in 1972. The newly remastered tracks, as well as the session outtakes, will also be a revelation even to those who know the album inside and out.

But perhaps no one feels the nostalgia, or the revelations, as profoundly as Keith Richards. There’s no denying that the album is quintessentially Keef in its swagger and the cocky sprawling grandeur of its musical scope. Hedged all about by rough edges, Exile’s elegantly wasted, slightly messy nonchalance is what imparts a frisson of raw truth to the overall beauty of the thing. Perhaps it’s not coincidence that Exile was recorded, amid scenes of legendary rock star decadence, in the vast, dank cellars beneath Richards’ home at the time, a palatial villa called Nellcôte, on the sunny French Riviera.

“I’m listening to these tracks, and suddenly I’m back in that old basement in the south of France,” marvels Richards, phoning in from another tropical paradise, a small island in the West Indies. “It’s amazing, especially for me, that ability to transport myself back in time.”

The Stones guitarist played a key role in preparing the Exile reissue, which will be released in three formats. The basic package is a CD containing newly remastered versions of the 18 tracks from the original album. The Deluxe version includes a bonus disc with 10 previously unreleased tracks from the album’s era, while the Super Deluxe release adds on two 30-gram vinyl albums containing the original album and bonus tracks, a DVD on the making of Exile and a 50-page collector’s book with photos.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Exile reissue project reunited Richards and his lifelong Glimmer Twin Mick Jagger with Jimmy Miller, the Rolling Stones’ late-Sixties/early Seventies producer who recorded and mixed the original album and many other great Stones records. A rock-solid drummer in his own right, Miller has always had some kind of primordial connection with the Stones’ profoundly rhythmic essence. Richards says, “I look back on it all, and I’ve got to say Jimmy Miller was the perfect producer for the Rolling Stones.”

Also onboard for the reissue project was the band’s present-day producer, Don Was, who sorted through hours of tapes to resurrect the bonus tracks. These include alternate takes of “Loving Cup” and “Soul Survivor,” plus an early version of “Tumbling Dice” titled “Good Time Women.” There’s also a cache of previously unreleased tracks, including “Dancing in the Light,” “Plundered My Soul,” “Following the River,” “Aladdin’s Story” and “Pass the Wine,” which has appeared on bootlegs under the working title “Sophia Loren.” For the Exile reissue, every effort was made to unearth fresh material from the vaults. In some cases, Jagger wrote and recorded brand-new vocals for what had previously been instrumental tracks. Richards overdubbed some guitar on a few tracks, but he stresses that he did as little as possible to the original recordings.

“I brushed a little acoustic guitar,” he says. “I can’t even remember on which song now. The original guitar track sort of stuttered and fell apart halfway through, so Don said, ‘Well, we better replace that.’ But that’s all I did really. As I said to Don, these tracks already are Exile, because they come out of that dusty basement. You can’t really screw around with them that much. Just tack them on. They are what they are, right from the same place.”

For Richards, the project triggered fond memories of those who have since departed the Stones, including original bassist Bill Wyman, and those who have since departed this life, such as session piano great Nicky Hopkins. “To hear Nicky Hopkins’ piano on ‘Sophia Loren’ was a treasure,” he says quietly. “And Bill’s solid as a rock, man. What a bass player! I’m actually more and more impressed with him, listening to this. You can get used to a guy, but listening back, going over this stuff to make this record, I’d say, ‘Jesus Christ, he’s better than I thought!’ ”

Richards also speaks fondly of his former Stones co-guitarist Mick Taylor, who joined in 1969 as a replacement for founding member Brian Jones. But Richards denies murmurings that Taylor, who left the band in late 1974, contributed overdubs to the reissue package. “That’s a rumor, babe,” he says. “If he was on there, I would know. We’ve had no contact with Mick for a long time.”

Hearsay seems to be dogging Richards’ footsteps these days. There’s another story going around that he has completely forsworn alcohol and all other intoxicants. “That’ll be the day, honey,” he says. The remark is punctuated by one of those long, slow Keef laughs, a groundswell that starts as a faint rumble in the nicotine-coated larynx and terminates in a rheumy expulsion of breath. “Let me put it this way: the rumors of my sobriety are greatly exaggerated. Hey, I cut down a little.”

Perhaps these suspicions of temperance are fueled by the disciplined rigor of the guitarist’s schedule these days. Along with preparations for the Exile reissue and DVD, Richards has been the subject of a new film biography directed by his longtime friend—and most dead-on impersonator—Johnny Depp. Keef is also completing a book-length autobiography, due out in October, with co-writer James Fox. “It’s the story so far, so to speak,” he says. “James has really put me down memory lane. It’s weird, man, trying to remember everything, and then reliving it as the memory comes back. Like, ‘Oh God, I gotta go through this thing twice!’ ”

But one life experience that Richards doesn’t seem to mind reliving is the making of Exile on Main St. It would be difficult to overstate the album’s importance in the great scheme of rock music. It is the climax of the Stones’ four-album winning streak that began with 1968’s Beggars Banquet and continued to gain momentum through the superb Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers, as the Sixties gave way to the Seventies. On Exile, the Stones attained a perfect balance between the American roots genres that had inspired them all along: blues, country, R&B, early rock and roll, and gospel. In this regard, Exile is almost like an Olympian athletic feat, one of those rare moments when nature, human effort and sheer random happenstance all come into graceful cosmic alignment.

“All those musical styles were part of what we’d been picking up while touring America,” Richards explains. “To us English boys, hanging out watching guys in America play music was like a dream come true, man. We were soaking stuff up like sponges wherever we could find it—south side of Chicago, those downtown juke joints…anywhere. New Orleans… Shit, man.”

Exile on Main St. is also one of rock and roll’s archetypal double albums. Although it was released a few years after the Beatles’ White Album, the Who’s Tommy and Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, Exile nonetheless had an immense role in establishing the double-vinyl album as a distinctive and unique art form. It’s an eloquent lesson in how open-ended jams like “I Just Wanna See His Face,” can slot in amid well-wrought rockers like “Rocks Off” and calypso-tinged acoustic ballads like “Black Angel.” Like all of rock’s great double albums, Exile takes the listener on an epic journey, one that commences with a sheer blast of energy on side one, moves into acoustic mode on side two and glides languidly to a stirring gospel conclusion over the course of sides three and four. In this regard, Exile represents the apotheosis of album rock—the move away from hit singles and into longer formats that had begun circa 1966.

“I think this is the first album where we didn’t have a 45 [rpm single] hit on it,” says Richards. “We picked some singles off it, but it was made for what it was. It was an album album. Of course, when it first came out, sales were not up to par to start with. But after six or nine months, they started to pick up as people got into it.”

Created with sublime indifference to the pop market, Exile on Main St. is one of the first DIY rock albums, recorded at the guitar player’s house at a time when that sort of thing simply wasn’t done. While Exile is not exactly lo-fi, there’s a delicious murkiness to the sound, a sense of mystery shrouded in messiness. It’s a sure bet that the New York Dolls were listening to Exile when they were getting started in the early Seventies. The roots of punk are right there in the snarling, brittle mesh of Keith Richards and Mick Taylor’s guitars. You can’t quite tell who’s doing what. It’s not too far a leap from that to the intertwined double-guitar approach of Television’s Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, which in turn gave rise to thousands of latter-day punk bands. And, of course, Exile also set the pattern for the dual-guitar dynamic that Richards and Ronnie Wood have pursued ever since Mick Taylor’s departure, a guitar style that Richards often describes as “an ancient form of weaving.”

So, many roads lead back to Exile on Main St. “The thing about recording Exile was it was the first time we weren’t in a studio to make a record,” Richards says. “It all sort of happened by circumstance, really. We all decided we were going to move out of England, due to great pressure from H.M. Government. So we said, ‘Let’s keep going. We’ll do it somewhere else.’ And we figured, Oh, the south of France sounds good. I mean what’s wrong with that?”

The “great pressure” he refers to came from Britain’s graduated tax laws, which required big earners like the Stones to pay some 90 percent of their income. That, combined with the band’s frequent drug busts and harassment from the police, forced them out of England. But the early Seventies were a time of heavy change for the Stones in many regards. They’d moved away from their manager, the notoriously belligerent Allen Klein, and launched their own label, Rolling Stones Records. Mick Jagger married Nicaraguan beauty Bianca Pérez Morena de Macias and settled down to a life of quiet domesticity in France, with the other Stones living nearby.

Richards had been together with Anita Pallenberg since 1969, after he’d won the striking blonde German/Italian fashion model away from Brian Jones. But, unlike Mick and Bianca, Keith and Anita had never felt the need to sanctify their union via anything as bourgeois as marriage. Their son, Marlon, was about a year and a half when they settled into Villa Nellcôte, a grand maison with stately neoclassical columns, capacious salons and a killer view of the Bay of Villefranche. Built in 1899, Nellcôte had been inhabited by a succession of financiers and diplomats before it became the domicile of Keith Richards and his bizarre ménage. “Anita and I went looking at a couple of places, but Nellcôte kind of chose us immediately,” he says. “It was just an incredible joint. It was like a mini Versailles, and it didn’t cost a lot.”

While the other Stones lived fairly quiet lives at home, Nellcôte quickly became Party Central, with an endless stream of friends, friends of friends, drug dealers, celebrities and gangsters passing through the villa’s grand portals. Guitars, amps, records, stereo gear, empty bottles, books, discarded foodstuffs and assorted pets were soon all over the floor and furnishings beneath Nellcôte’s magnificent crystal chandeliers. Richards says that Marlon, now in his early Forties, has no memories of the place. “He was too young, probably around two years old,” the guitarist says. “He was running around bare-assed. Although he probably remembers the smell.”

Nellcôte’s basement became the Stones’ recording studio by default. The original plan was to find a commercial facility nearby. “We figured there’s gotta be some decent studios in Cannes or Nice or somewhere around there, even if it was Marseilles,” Richards says. “But we checked them all out, and it was pathetic. This was 1971. No doubt they’ve got great joints there now, but then, no. It was, like, forget about it. So then it became, ‘Let’s rent a house and see if we can do it there.’ Which is where the idea of bringing our mobile truck came in.”

That would be the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio. Though mobile recording facilities are now commonplace, they were in their infancy in the early Seventies. The innovative Stones had put their own recording truck together, in 1968, though initially it was more as an income source than for their own use. The unit had been loaned out to Led Zeppelin for their third and fourth albums, and the Stones had used it when recording tracks for Sticky Fingers at Jagger’s home, Stargroves. It had also been used for “location recordings for TV and the BBC, and stuff like that,” Richards explains. “But suddenly we realized, We got a truck, man—a mobile control room. But then we couldn’t find a house to record in. So we ended up using my basement.”

Below Nellcôte’s ground floor lay three levels of basement, subdivided into chambers of various sizes and shapes. Together with pianist/road manager/de facto sixth Stone Ian Stewart, Richards set about hanging microphones and carpets to control acoustic reflections. Home recording was virtually unheard of in 1971. The equipment was bulky and expensive and, thus, strictly the province of rock royalty like the Beatles and Stones. People didn’t really know much about recording in spaces that weren’t acoustically designed for that purpose. The Stones were moving into uncharted territory when they ventured below stairs at Nellcôte.

“There were all these little subdivisions in the basement, almost like booths,” Richards recalls. “So what would happen was that, for a certain sound, we’d schlep an amp from one space to another until we found one that had the right sound. Sometimes the guitar cord wasn’t long enough! That was in the beginning, anyway. But once we started to work there, my little cubicle became my cubicle, and we didn’t change places much.

“But at first, it was just a matter of exploring this enormous basement, saying, ‘What other sound is hiding ’round the corner?’ ’Cause you’d have weird echoes going on. Sometimes we wouldn’t be able to see each other even, which is very rare for us. We usually like to eyeball one another when we’re recording.”

Summer came to the French Riviera as sessions got underway. The basement was very hot and humid, and keeping guitars in tune was sometimes a challenge. The environment no doubt inspired the album’s working title: “Tropical Disease.” But it’s the dust that Keef recalls most vividly.

“It was a dirt floor,” he says. “You could see somebody had walked by, even after they disappeared ’round the corner, because there’d be a residue of dust in the air. It was a pretty thick atmosphere. But maybe that had something to do with the sound—a thick layer of dust over the microphones.”

Despite the challenging environment, the songs came fairly quickly. Before leaving England, the Stones had started some tracks at Olympic Studios in London and at Stargroves. Down in France, they picked up these threads. Keith remembers the acoustic-driven country number “Sweet Virginia” as one of the first they worked on. “I can’t remember if that was the actual first,” he says. “That would be beyond even my phenomenal memory. But I recall that Mick had ‘Sweet Virginia’ prepared and ready to go. I have a feeling that we’d been playing around with that one on the last sessions. Maybe on Sticky Fingers, or whatever. So it was a work in progress.”

Another work in progress was the aforementioned “Good Time Women” which soon became Exile’s one big single, “Tumbling Dice.” “I know we did that one fairly early on in France because I remember the weather,” Richards says. “The basic idea, as you can hear from ‘Good Time Women,’ was already there. But it took a while for it to turn into ‘Tumbling Dice.’ We were stuck for a good lyrical hook to go with this really great riff, so we left it in abeyance for a bit. And then I think Mick came up with the title ‘Tumbling Dice,’ although he may have got it from someone else. Ha!”

The evolution from “Good Time Women” to “Tumbling Dice” is a classic example of the Jagger-Richards songwriting partnership at work. It also exemplifies the way the Stones will often allow a track to develop over time, re-recording it repeatedly and often in many different locales. “If you chase a song far enough, you’re gonna corner it—like a rat!” Richards says with a laugh.

But the pace was generally brisk. “Sometimes we’d get two tracks in a night down there,” he says. “And then there’d be other times when we’d be three days on one song.”

The work schedule was fairly regular, the guitarist recalls. “Charlie Watts was living a long way away, a six- or seven-hour drive, for some reason. But then drummers are quirky, you know. So we’d generally work for four days a week, five at a push. But the weekends would be off.”

Various Stones would sleep over at Nellcôte from time to time, but occasionally inspiration struck when some of the members were away. Such was the case when Richards’ signature track, “Happy,” came into being.

“It was pretty early in the afternoon,” he recalls. “Jimmy Miller was there checking on the previous night’s session tapes. I said, ‘Oh shit, I’ve got an idea, Jimmy.’ He said, ‘Well, just lay it down with the guitar.’ So I start laying it down, and suddenly Jimmy’s behind me playing the drums. He’d come down from the truck, and I hadn’t even noticed. I’m just hammering away, figuring this thing out. Suddenly I hear these great drums behind me, and now it’s starting to rock. It’s one of these ‘three feet off the ground’ feelings. And then, suddenly, I hear this baritone sax, and there’s Bobby Keys honking away. Suddenly it’s becoming very happy.”

Even the song’s lyrics sprang from that initial inspiration. “Most of ’em anyway, in some garbled form,” Richards says. “The whole idea was there. ‘I never kept a dollar past sunset…’ That was all there.”

The preeminence of “Happy,” at the top of the album’s third side, coupled with the preponderance of great Keef guitar hooks on Exile, has led some observers to describe the disc as “Keith’s album.” But the guitarist is having none of that. “I don’t really get that,” he says. “Mick was incredibly involved. Look how many songs there are. And he wrote the bulk of the lyrics. He was very involved. I don’t think I was putting in more than anybody else. Charlie was amazing. Everybody was in great form.”

Exile does contain some of the most sympathetic guitar teamwork that Richards and Mick Taylor ever committed to disc. They mesh seamlessly, almost telepathically, on track after track. With the exception of “Happy” and possibly “Ventilator Blues,” Richards left the bulk of the slide guitar work to Taylor. But where Taylor’s leads can stand out a little too assertively on some earlier Stones recordings—particularly the live Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out album—here he’s dug in deep, roiling along with Keef and fully integrated into the guitar juggernaut. Perhaps this is in part due to the album’s ad hoc recording circumstances, combined with the fact that Taylor had been a Stone for about two years at this point and was well settled in. And maybe by living close by and actually sleeping over at Nellcôte on many occasions Taylor had fallen into sync with Richards on some elemental level.

“I also think it was because we were writing songs on the spot,” Richards says. “So I automatically fell into doing the chording and figuring out the whole thing, which gave Mick Taylor a freedom. He just came up with line after beautiful line. What a player, man.”

Exile is also awash in great guitar hooks based around Richards’ signature five-string open G tuning (omitting the low E string and tuned, low to high, G D G B D). He’d first used this tuning on “Honky Tonk Women” in 1969 and had integrated it into his approach more and more thoroughly on Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers. But it really explodes on Exile and is the secret behind riff-mad classics like “Rocks Off,” “Tumbling Dice” and “Happy.”

“I was really bathing in that stuff at the time, finding out more and more about the tuning as I was going along,” Richards acknowledges. “In a way, with a lot of the five-string stuff on Exile, I’d just found that space. You’re listening to me in school!”

For a few magic months at Nellcôte, everything seemed to fall into place. With sax player Bobby Keys and trumpeter Jim Price right on the premises, the horn charts on Exile are a deeply organic part of the music, rather than an overdubbed afterthought, as horn parts all too often tend to be.

“I think that’s another one of the beauties of the album,” Richards says. “The fact that the horns are actually playing with the band. There is something to be said for having it all in one room. Bobby and Jim were amazing, ’cause they had to make up their parts virtually on the spot. The songs were coming out two or three a night. Sometimes I’d lay an idea for a song on them at the end of a session, early in the morning, so they’d have it in their heads by the time they got back the next day. There were only two of them, a sax and a trumpet, but Jimmy played great trombone as well, so we’d double them up until they became a section.”

Many extraordinary musicians passed through Nellcôte during the Exile sessions. The list of those who were there but didn’t play on the album is as impressive as the roster of gifted players who did. John Lennon stopped by at one point, drank a bottle of red wine and vomited. Country rock pioneer Gram Parsons and his girlfriend Gretchen were long-term houseguests. The American musician and tunesmith was a major factor behind the Stones’ pronounced country influence in the early Seventies; he was also a close friend and drug buddy of Keith’s. There has been much speculation about Parsons’ uncredited, behind-the-scenes role in writing many of the Stones’ country-tinged classics. But if he was hanging around Nellcôte for so long, how come he didn’t end up playing on Exile? Or did he?

“No, he didn’t,” Richards replies. “But why he didn’t play is a good question. Gram and I would play around a lot upstairs in the living area, and he would play with Mick [Taylor] a lot up there. So I don’t know… Gram was a little shy, and we were too busy to say, ‘Hey, Gram, come down here. We need another guitar.’ He would distance himself from us when we were working. He’d come and listen a bit, but that was it. But you know, if I have a friend—and Gram was my friend—Mick sometimes gives off a vibe like, ‘You can’t be my friend if you’re his.’ It could be a bit to do with why Gram’s not playing on the record.”

The basement sessions were a separate world from the ’round-the-clock party taking place upstairs and in a small adjacent guesthouse, where the roadies were residing. “Upstairs was a continual ball, if you know what I mean,” Richards says. “Unfortunately the Stones were rarely involved, ’cause we were busy working.”

But every party has its price and painful morning-after hangover. And on October 1, 1971, burglars got into Nellcôte and made off with somewhere between 11 and 17 guitars (accounts vary), purportedly in retribution for money not paid to dope dealers who had been supplying guests at the villa. For Richards, the memory is especially unpleasant.

“When they put the documentary together for Exile, they showed me some footage, and there I am, holding my favorite stolen guitar, a 1964 Telecaster. It was like, ‘Oh baby, don’t rub it in.’ There she was. Had a lovely sound. I just got used to that one, you know? I can play almost any Telecaster, but the more you play just the one, the more it becomes attached to you. I almost went into a blank after the guitars were stolen. I didn’t want to think about it. But I slowly started to build up a new collection since then. I haven’t lost one since. I learned my lesson: don’t leave them hanging around on a Saturday night!”

Just about every notable rock and roll junkie has a tale of guitars going missing, and Richards is no exception. It’s well known that he and Pallenberg were heavily into heroin during their tenure at Nellcôte. In one famous incident, the couple were so out of it that they accidentally set fire to their bed. Observers have marveled at Richards’ ability to be as creative and prolific as he was during the making of Exile while seriously strung out on dope.

“Well, I’m not going to get into those questions.” He laughs and then assumes a thick Northern English accent. “ ‘Did Charlie Parker play better because he was on the stuff?’ I found that [heroin] didn’t inhibit whatever it was I wanted to do. If I thought it was diminishing me or that I wasn’t putting my fair share into the music, then I’d have been off the stuff right away. And that’s a fact. I’m a funny kind of guy. I’ve got a metabolism you wouldn’t believe.”

Still, as the glorious Mediterranean summer gave way to winter’s chill, the idyll at Nellcôte was clearly drawing to a close. The local police were starting to get ugly, and the Stones’ phenomenal creative streak was wending toward a natural conclusion. Richards remembers “Casino Boogie,” as one of the last Exile songs to fall into place.

“I think when we got to ‘Casino Boogie,’ Mick and I looked at each other and just couldn’t think of another lyrical concept or idea for the song.” At that point Richards recalled another great junkie artist, the novelist William Burroughs. “I said to Mick, ‘You know how Bill Burroughs did that cut-up thing—where he would randomly chop words out of a book or newspaper and then try to sort them up?’ That’s how we did the lyrics for ‘Casino Boogie,’ and that was Bill Burroughs’ biggest influence on the Rolling Stones.”

At the end of November, barely one step ahead of the police, the Stones decamped for Los Angeles. Working at the historic Sunset Sound studio, they began laying overdubs onto the tracks they’d cut at Nellcôte. Billy Preston, who just a couple of years before had worked with the Beatles on Let It Be, lent his formidable piano and organ talents to “Shine a Light.” Pedal steel ace Al Perkins imparted a tearful country lilt to “Torn and Frayed,” and upright bass player Bill Plummer left his mark on no fewer than four tracks: “Rip This Joint,” “Turd on the Run,” “I Just Wanna See His Face” and “All Down the Line.” A phalanx of backing vocalists added loads of soul and gospel grandeur. Among their ranks, on “Let It Loose,” was none other than Mac Rebennack, better know as the celebrated New Orleans pianist and singer Dr. John. “He just walked in,” Richards recalls. “Mac Rebennack’s like that. If there’s music going on, in one way or another, he’s gonna get his ass in there. I love the guy.”

By the time overdubs were completed, there were too many tracks in the can to do a single album. And so the Rolling Stones joined the Beatles, the Who, Jimi Hendrix and other classic rockers who have left the world with a monumental double-album statement.

“The fact that the Beatles had done it probably gave us a sense of, ‘Oh, there is a precedent,’ ” Richards says. “But our point was that we’d put down this body of work and when it came to chopping it down to one album, nobody could agree on which songs to cut. After a while, Mick and I looked at each other and said, ‘This is impossible. How about a double? This is all one piece. It’s gonna be unique just because of where it was recorded and the way it was recorded.’ We sort of nodded at one another and said, ‘Let’s go for it.’ Which gave us hell from the record company: ‘Aw, the public hates double albums,’ and all of that. But we insisted.”

Richards adds that mixing the album was daunting, “only from the point of view that there was so much of it. Mixing a double album was different than mixing a single album. So we were going into uncharted territory. Mick and I would look at one another and say, ‘How many more songs to go?’ mopping our brow, so to speak. But I can’t remember it being that difficult. I think we were so intimate with the tracks by then that, listening to the overdubs and mixing, it just put the icing on the cake. I remember it as being a very joyous couple of weeks. We were all on top of it. Jimmy Miller, all of us—we all knew what we were doing. It was just a matter of watching it fall into place. It was one of those rare things: a perfect mixing session.”

Sequencing the album, however, was more of a chore. As mentioned previously, much of Exile’s magic lies in the way the songs flow from one to the next. But that magic didn’t just happen spontaneously.

“Trying to get the track order down was murder, actually,” Richards says, laughing. “I’d be sending cassettes to Mick in the middle of the night—putting my version of what the order should be under his door. I’d come back to my room and there’d already be a cassette under my door with his version of what it should be. ‘Hey, Mick, that’s pretty good, but you’ve got four songs in a row in the same key. We can’t do that!’ You’d come across all these weird little problems that you never thought of. It was like making a jigsaw puzzle. By the time I got the final version, I didn’t give a shit anymore!”

While the music on Exile is a product of that summer in the south of France, the album’s packaging and conceptual framework were largely inspired by L.A.’s late-Seventies aura of faded Hollywood decadence. The “Main Street” referenced in the title was a seedy thoroughfare in downtown Los Angeles, which harbored a Chinese restaurant that the Stones liked to frequent at the time. The black-and-white cover images—a bizarre and vaguely disquieting assortment of showbiz freaks and geeks from days gone by—were snapped from the walls of an L.A. tattoo parlor by photographer Robert Frank. All these elements contributed to a wistful fin-de-siècle mood that permeates the album packaging and perfectly reflects the mood at the time of the album’s creation. It was indeed the end of an era. The Sixties were dead and long gone by the time Exile was released on May 12, 1972; so were Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison, as well as the Beatles, a band with which the Rolling Stones had long been associated. The hippie dream had failed to materialize.

And so on Exile, the Stones seemed to be enshrining themselves among the yellowing photos of yesteryear’s forgotten entertainers. A series of 12 postcards included with the original album—and faithfully reproduced in the Deluxe reissue—offered a comedic depiction, also in blurry black and white, like an old movie, of the Stones arrival “in exile.” The caption for the final card reads:

“Taylor realizes the fall is complete, ‘they’ll be Forever Exiles on Main Street.’ He suggests early retirement. ‘No better not, it’s getting quite late and we’ll be fogged in forever quite soon.’ ”

The reference to “early retirement” is especially rich 40 years on. But what was it that enabled the Stones to not only endure but also triumph when so many of their Sixties contemporaries had either dropped dead, split up or become woefully irrelevant?

“I’m probably the worst person in the world to answer that question,” Richards replies. “I suppose at that particular period, the early Seventies, everything else had run out of steam—the Beatles and whatever. And I think maybe it’s just the fact that we kept going that did it. At the same time, what was picking up then was stuff like Zeppelin. A whole new energy came in from another generation. There was a lot going on. As I think about it, we didn’t see any reason to stop, and we were on a roll. So we just followed it. And suddenly, you find you’re 66 years old.”

As for the possibility of the Rolling Stones or some younger band making a modern-day equivalent of Exile on Main St. today, Richards demurs. “I’m not saying it’s impossible,” he says. “But, hey, it’s probably highly unlikely.”

“I knew the spirit of the Alice Cooper group was back – what we were making was very much an album that could’ve been in the '70s”: Original Alice Cooper lineup reunites after more than 50 years – and announces brand-new album

“The rest of the world didn't know that the world's greatest guitarist was playing a weekend gig at this place in Chelmsford”: The Aristocrats' Bryan Beller recalls the moment he met Guthrie Govan and formed a new kind of supergroup

![[from left] George Harrison with his Gretsch Country Gentleman, Norman Harris of Norman's Rare Guitars holds a gold-top Les Paul, John Fogerty with his legendary 1969 Rickenbacker](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/TuH3nuhn9etqjdn5sy4ntW.jpg)