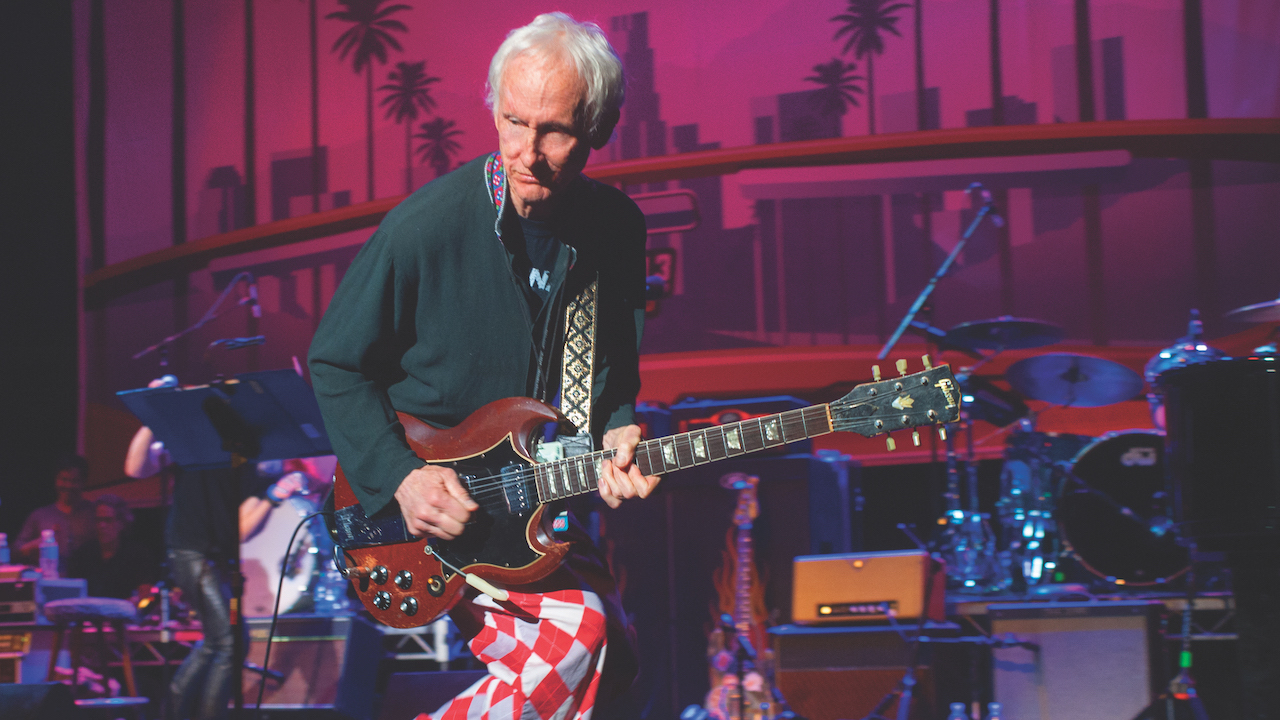

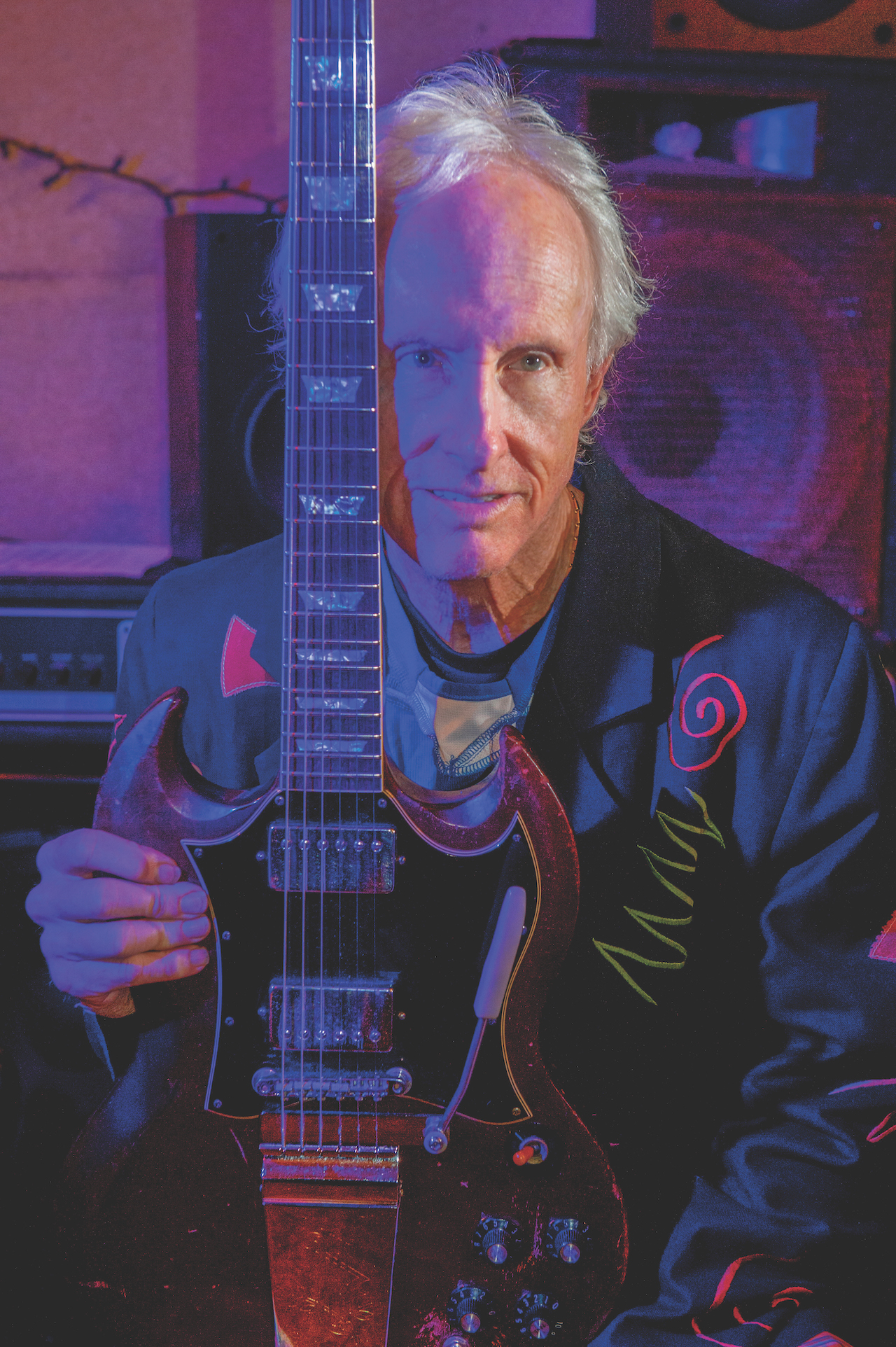

“Riders on the Storm started off as a surf tune – then it somehow morphed into what it became…” Robby Krieger on honing his Doors guitar tone, overcoming “dentist’s syndrome”, and why slide guitar is the ultimate way to express yourself as a player

Robby Krieger breaks down his new album with the Soul Savages’ new album, and details his struggles to come up with his own sound during his time with the Doors

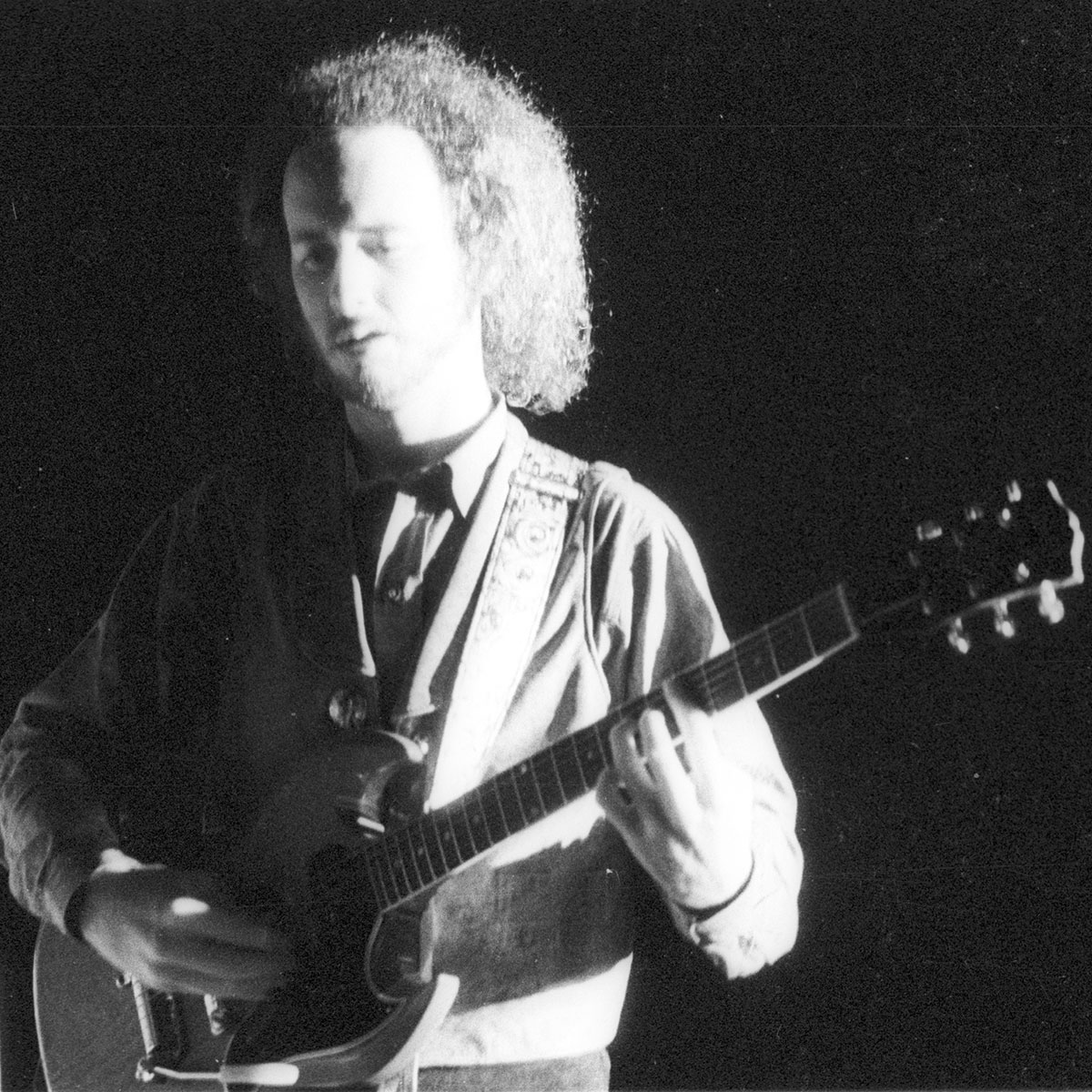

Robby Krieger's legendary status is assured, having recorded six classic albums with The Doors between 1967 and 1971, starting with their eponymous debut and concluding with L.A. Woman, due to the untimely death of singer Jim Morrison. Krieger’s unique finger-picked, slide stylings are all over the records, becoming as much a part of the band’s signature sound as Ray Manzarek’s keyboards.

Krieger’s writing was equally vital to the success of the band, coming up with many of their most loved songs. The Doors made two more albums, Other Voices (1971) and Full Circle (1972), after Morrison’s death, working as a three-piece – both strong albums that are often overlooked due to the absence of the charismatic Morrison.

Krieger had two short-lived bands – Butts Band and Red Shift – through to the end of the ’70s before moving into the jazz-fusion arena in the ’80s with his self-titled album released in 1985. By 1991, he had formed his own touring band, the Robby Krieger Band.

With interest in the Doors’ catalog always strong, Krieger succumbed to the inevitable in 2002, hooking up with Manzarek to temporarily reform the band under the banner Doors of the 21st Century with Cult frontman Ian Astbury on vocals.

Krieger has continued to record intermittently, with Cinematix in 2000 and Singularity in 2010, but he remains a fairly constant fixture on the live circuit, both as a solo artist with his own band and as a special guest with numerous rock legends, including Gov’t Mule and Alice In Chains.

Krieger has just released his first album since 2020’s The Ritual Begins at Sundown. The self-titled debut album for the newly formed Robby Krieger and the Soul Savages sees Krieger returning to the all-instrumental, jazz-fusion vibe of his earliest solo work. The warm, organic feel of the record harks back to the golden age of fusion.

How did the album come about?

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I’d just gotten over a cancer scare, and a good friend of mine, Kevin Brandon, who’d played bass on Singularity in 2010, had just escaped near death. He’d been in bed for a year. He wanted to play, so we got together with another couple of friends, Dale Alexander on drums and Ed Roth on keyboards, and we started jamming for fun at my studio in Glendale, California.

“Pretty soon, Dale had to go back to Minneapolis, so we ended up with Franklin Vanderbilt on drums, who plays with Lenny Kravitz, and that became the group.”

Had you written anything beforehand, or was everything created in the studio?

“We went into the recording process without any set ideas. I find that to be the most fun way to do it. Even way back with The Doors, when we recorded L.A. Woman, that’s how we did that record. We’d just start playing in our rehearsal space and the songs would come out somehow.

“We have a pretty cool setup in my studio, including some great state-of-the-art plug-ins combined with some really good old-school equipment. The idea was to try to keep the process and the sound as old-school as possible. We mainly played live together as we recorded it.”

There’s a cinematic feel to a lot of the tracks. A lot of them sound like they could have come from ’70s detective shows.

“You’re right, a lot of the stuff did sound like it could’ve been from soundtracks, but we didn’t think, as we were creating the album, 'Hey, let’s make it like a TV show or something.' It just seemed to come out that way. I’d definitely like someone to pick up the tracks for something like that. [Laughs] A Day in L.A. sounded to us like it could have come from a cool comedy score.”

There are great guitar tones all over the album. What are the main guitars and amps we’re hearing?

“Pretty much my ’67 Gibson SG with a 4x10 Fender Blues DeVille. There’s also a bit of electric sitar on a couple of tracks. Most of the delays were added after I’d laid down the guitar tracks. I prefer to record with a fairly straightforward sound and then, if I want to add something, that’s an option. But I’m not stuck with one particular effect in case I change my mind later on.”

The album feels like a throwback to the golden age of jazz fusion, with a good chunk of funk in the mix. What sort of stuff influenced you?

“I like all kinds of music, but for this album, Kevin Brandon had played with Aretha Franklin for years, and the other guys had played with a lot of great jazz and blues artists. I think that’s probably a large part of what drove the overall feel of the record.”

The trademark of the great albums from that era is that all the musicians had great chops.

“Exactly, and that’s what was so great working with the guys on this record, the way they can push you to another level because they’re all at the very top of their game.”

The record has a bright, summery feel, which is ironic as it came out in January!

“I never actually thought about that – that’s funny. Maybe if it takes a while for the album to catch on, it’ll be just in time for the summer. [Laughs]”

You come up with a lot of strong melodies, some which could be vocal lines. Do you ever think in terms of vocals when you’re coming up with melodic ideas?

“Mostly, the melodies come to me without any notion of words in mind. If I do come up with lyrics, it would be later – that’s the way I always did it with The Doors. My greatest wish is to be able to have one of those all-time great instrumental hit records, like [Santana’s] Samba Pa Ti or something.”

In terms of the production of the album, there’s a lot of space around the instruments. What’s the secret to that?

“You’re right about that, and it’s not easy to do as these days everybody wants to fill every space. I call it 'dentist’s syndrome' – the need to fill every hole. [Laughs] These guys are all seasoned pros, and they know when to play and when to lay back, and I think, if there is a secret, it’s the ability to know when to let the music breathe. There’s a real art to that, so I’m glad you noticed that.”

Your slide playing is unusual in that you tend to avoid the traditional blues clichés in favor of a more fluid, microtonal approach.

“Yeah, ever since the Doors’ Moonlight Drive. I don’t think anybody would have thought of doing the slide part like that. I always wanted to have my own sound. I do think my slide playing is kind of different, even though I can’t help being influenced by Duane Allman and some of the greats of slide.

“I think slide playing is the ultimate way to express what you want to play, as you’re not bound by the frets. Hopefully, if you don’t mess it up [Laughs], if you’re careful, you can really find some interesting, expressive nuances.”

Ricochet Rabbit goes down the Wes Montgomery route of voicing the melody in octaves.

“You can’t really play octaves without people thinking of Wes or George Benson. That’s actually one of my favorite tracks on the album. I was just fooling around with the part and one of the guys said it sounded like something we can work with. The slide solo takes it to another place, though, which I think is cool.”

Blue Brandino finds quite a different approach to the rest of the record, with a grittier, hard-edged blues sound to your guitar. Have you ever thought about a straight blues album?

“I wouldn’t mind trying something like that. I love blues, but I think it’s hard to come up with something a little different when you’re restricted to playing blues.”

What are the standout records when you look back over your playing with the Doors?

“Definitely the first, self-titled album [from 1967], as we’d had months and months of playing the stuff every night at the Whiskey. I think L.A. Woman is probably my next favorite, mostly because of the way we recorded it, as I say, as we were jamming on a lot of the tracks until they became songs.

“Riders on the Storm started off as a surf tune – then it somehow morphed into what it became. After Jim passed, we did a couple of albums with John, Ray and me. I think there were some great songs on those albums, although they don’t get a lot of attention.”

Do you ever listen to the Doors’ albums?

“No, not really, unless I’m planning to include a song in one of my live shows that I haven’t played for many years. I hear a lot of our stuff on the radio all the time anyway. I think the songs still hold up pretty good.

“What makes me say that is when I look at the people who come to my live shows and you’ve got original fans, plus a big percentage of younger people who’ve also discovered the band. They really seem to be into what the Doors did.”

What do you think of your own playing from back then? Do you wish you’d done things differently?

“No, I don’t do that. In fact, I think it’s actually probably more the other way around, where I’ll think, ‘Wow, how did I do that?” [Laughs] I never actually sit down and practice as such these days, unless I’ve got some shows coming up, when I will maybe do that to a degree. [Laughs]

“I think I always learn more new stuff when I’m playing gigs. It seems that the pressure to create in the moment can be very inspirational.”

Do you still have many guitars from the ’60s?

“No, very few. I have about 30 guitars, but only one is from when I was in the Doors, and that’s my ’54 Les Paul Black Beauty, which I used on the first couple of albums. My original SG was stolen. I got another ’67 years later that I still use.

“I don’t know what I did with all the guitars I had. They weren’t collectable in those days, so I sold them or gave them away or whatever. I wish I hadn’t. [Laughs]”

What keeps everything fresh and stimulating for you after 60 years of playing and touring?

I’ve got another album recorded and ready to go – I’m just looking for a label. It’s an instrumental reggae album

“In some ways it’s more exciting, because in those days I was more in the background. Jim was out front, and John, Ray and I were in the background, in the shadows. Nowadays, it’s the Robby Krieger Band, and I’m expected to talk to the audience and all that stuff, which is fun, but I kind of wish I was still hidden away. [Laughs]”

What’s coming up for you?

“I’ve got another album recorded and ready to go – I’m just looking for a label. It’s an instrumental reggae album. Phil Chen was a good friend of mine; he played bass in the Butts Band, which I formed with Ray Manzarek and John Densmore in 1973. We recorded our first, self-titled album in Jamaica, which thrilled Phil, as he got a chance to see a lot of his family members who lived there.

“He was a great bass player, playing with Jeff Beck, Rod Stewart and other artists. He became very ill and passed away at the end of 2021. Before he passed, we had discussed and recorded an album of instrumental reggae tracks. I’m looking for a label to release the record toward the end of summer, so that will be my focus once the promotion of the current album finishes.”

- Robby Krieger And The Soul Savages' debut album is out now.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

“I suppose I felt that I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I’d put into it. My head was huge!” “Clapton is God” graffiti made him a guitar legend when he was barely 20 – he says he was far from uncomfortable with the adulation at the time

“I was in a frenzy about it being trapped and burnt up. I knew I'd never be able to replace it”: After being pulled from the wreckage of a car crash, John Sykes ran back to his burning vehicle to save his beloved '76 Les Paul